Transcription

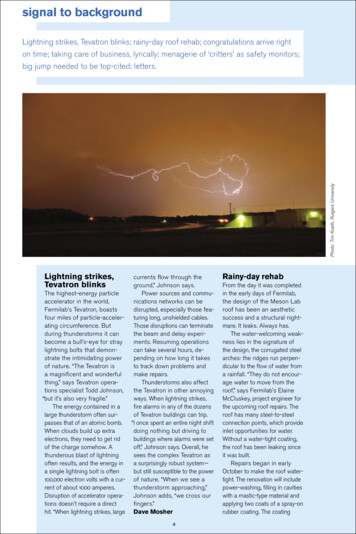

signal to backgroundPhoto: Tim Koeth, Rutgers UniversityLightning strikes, Tevatron blinks; rainy-day roof rehab; congratulations arrive righton time; taking care of business, lyrically; menagerie of ‘critters’ as safety monitors;big jump needed to be top-cited; letters.Lightning strikes,Tevatron blinkscurrents flow through theground,” Johnson says.The highest-energy particlePower sources and commuaccelerator in the world,nications networks can beFermilab’s Tevatron, boastsdisrupted, especially those feafour miles of particle-acceler- turing long, unshielded cables.ating circumference. ButThose disruptions can terminateduring thunderstorms it canthe beam and delay experibecome a bull’s-eye for strayments. Resuming operationslightning bolts that demoncan take several hours, destrate the intimidating powerpending on how long it takesof nature. “The Tevatron isto track down problems anda magnificent and wonderfulmake repairs.thing,” says Tevatron operaThunderstorms also affecttions specialist Todd Johnson,the Tevatron in other annoying“but it’s also very fragile.”ways. When lightning strikes,The energy contained in afire alarms in any of the dozenslarge thunderstorm often surof Tevatron buildings can trip.passes that of an atomic bomb. “I once spent an entire night shiftWhen clouds build up extradoing nothing but driving toelectrons, they need to get ridbuildings where alarms were setof the charge somehow. Aoff,” Johnson says. Overall, hethunderous blast of lightningsees the complex Tevatron asoften results, and the energy ina surprisingly robust system—a single lightning bolt is oftenbut still susceptible to the power100,000 electron volts with a cur- of nature. “When we see arent of about 1000 amperes.thunderstorm approaching,”Disruption of accelerator operaJohnson adds, “we cross ourtions doesn’t require a directfingers.”hit. “When lightning strikes, large Dave Mosher4Rainy-day rehabFrom the day it was completedin the early days of Fermilab,the design of the Meson Labroof has been an aestheticsuccess and a structural nightmare. It leaks. Always has.The water-welcoming weakness lies in the signature ofthe design, the corrugated steelarches: the ridges run perpendicular to the flow of water froma rainfall. “They do not encourage water to move from theroof,” says Fermilab’s ElaineMcCluskey, project engineer forthe upcoming roof repairs. Theroof has many steel-to-steelconnection points, which provideinlet opportunities for water.Without a water-tight coating,the roof has been leaking sinceit was built.Repairs began in earlyOctober to make the roof watertight. The renovation will includepower-washing, filling in cavitieswith a mastic-type material andapplying two coats of a spray-onrubber coating. The coating

symmetry volume 03 issue 08/09 oct/nov 06It absolutely had toarrive on timeThe inaugural beam for theCERN Neutrinos to Gran Sasso(CNGS) project took just 2.5milliseconds to fly 732 kmthrough the earth from Geneva,Switzerland, to its destinationat the Gran Sasso undergroundlaboratory near Rome onMonday, September 11, 2006.But in preparation for the dedication ceremonies at IstitutoNazionale di Fisica Nuclearethat day, a congratulatory gifthad to make its own quick transit by air across ten times thatdistance (more than 7100 km),from Fermilab to Gran Sasso.The gift was a framed poster,featuring a picture of Fermilab’sWilson Hall at sunset, mountednext to an image of the minehead for the SoudanUnderground Laboratory innorthern Minnesota—representing the beam origin and detector hall for Fermilab’s NuMI/MINOS beamline and experiment, covering a similar distancethrough the earth as the CNGSbeam. Fermilab director PierOddone had written his congratulations and best wishes(in Italian) across the center,before the framed greetingflew overnight from Chicagoto Rome. “We had it allpacked up and found out theyneeded it for some kind of5presentation the next day,” saysFermilab shipping managerClaudie King. “We put it on thenext flight.” The greeting arrivedon time and was presented toEugenio Coccia, director of theLaboratori Nazionali del GranSasso (photo).Like Fermilab’s beamline,CNGS will help physicistsunderstand the role that thepuzzling neutrinos played in theearly universe. “Of all the knownparticles, neutrinos are the mostmysterious,” says Oddone. “Inthe years ahead, neutrino experiments at Gran Sasso andaround the world will discoverthe fascinating secrets of neutrinos and how they shaped theuniverse we live in.”Siri SteinerPhoto: Laboratori Nazionali del Gran SassoPhoto: Fermilabmaterial, used in many industrial roofing applications, willdry as a sheet. “The material’smanufacturer said the MesonLab roof was one of its mostunique uses,” McCluskey says.The trademark Fermilabcolors, bright blue and orange,will also be restored, honoringthe original vision of foundingdirector Robert Wilson anddesigner Angela Gonzales. Theduo attended to virtually everydetail of the site’s appearance.At the Meson Lab, they calledfor the use of corrugated steelculverts, laid side by side, tocreate giant scallops, with anorange inner surface anda blue outer surface to giveadded texture. McCluskeysays, “The architectural legacyof Dr. Wilson is something wetry to preserve as we remodelbuildings and look to futurefacilities.”The renovated Meson Labwill house R&D projects for theproposed International LinearCollider. The west side of thebuilding will belong to thedevelopment of detector components; the east side, to thetesting of superconductingradiofrequency cavities for particle acceleration. Repairs tothe roof are expected to becompleted in two months–if theweather cooperates.D.A. Venton

signal to backgroundTakin’ care of(SLAC) businessWhen 20-year-old RyanAuer set out to find his veryfirst job, he didn’t expectto wind up at the StanfordLinear Accelerator Center,let alone on stage in front ofover 1000 people at the lab’sannual Family Day. A collegesophomore, Auer workedthis summer with the campus Heating, Ventilating, andAir-Conditioning engineers.The job inspired him tochange his major from civilto mechanical engineering.As a parting tribute beforeheading back to school, hewrote and performed theseSLAC-happy lyrics to theBachman-Turner Overdrivetune Takin’ Care of Business.Rachel CourtlandPhotos: Diana Rogers, SLACWatch a performance of the songin the online edition of symmetry atwww.symmetrymagazine.org.6

Takin’ Care of Businessby Ryan AuerWe made our debut,Back in 1962;It’s all controlled at MCC.Faster than the speed of light,SLAC hosted the first website,And you can take a tour here for free.The Archimedes text,What will they uncover next?Come and view the linac from afar.The wires intertwine,Up and down the beamline,We’ve got an experiment called BaBar.Three Nobel Prizes,And buildings of great sizes,We get our funding from the DOE.Particle acceleration,And our own fire station,We’ve got the great Dr. Panofsky.Several injectors,And we’ve got 30 sectors.We’re just right off the interstate.PEP & SPEAR,You can find it all right here,Just come on in through Alpine Gate.And we’ll be.Takin’ care of business, here at SLAC,Takin’ care of business, no turnin’ back,Takin’ care of business, everyday,Takin’ care of business, and everything’s okay.Visit SSRL,Or come stay at our hotel,Come to watch the gamma rays burst.If the tunnels are too small,Just come to Collider Hall,But please make sure that safety comes first.Now before you embark,Don’t forget about the quark,Discovered in End Station A.I hope you liked my song,Now I must be movin’ on,Enjoy the rest of Family Day.And we’ll be.Takin’ care of business, here at SLAC,Takin’ care of business, no turnin’ back,Takin’ care of business, everyday,Takin’ care of business, and everything’s okay.7symmetry volume 03 issue 08/09 oct/nov 06And we’ll be.Takin’ care of business, here at SLAC,Takin’ care of business, no turnin’ back,Takin’ care of business, everyday,Takin’ care of business, and everything’s okay.

Photo: Butch Hartman, Fermilabsignal to backgroundSafety crittersmonitor lab siteThe instrumentation team ofFermilab’s Environment, Safety& Health Section is the caretaker of a unique menagerie:albatrosses, chipmunks, hippos, pterodactyls, scarecrows,and an aardvark to name afew. These critters are radiation detection instruments,designed and built in-house.“Everyone here knows whatthey are, but no one else inthe world would,” says ButchHartman, team co-leader.The level of radiation atFermilab is stringently moni-tored, and radiation at Fermilabconsistently falls below radiation standards set by the USDepartment of Energy.Throughout the site, radiationlevels are maintained at thenormal, background levelsfound in the natural environment; higher levels are foundonly inside accelerator enclosures and at a few posted,fenced-off locations. Workerswho enter experimental areasthat might be exposed to measurable levels of radiation weardetection badges. The majorityof radiation exposure occurswhen accelerator componentsneed repair; the maintenanceinside accelerator enclosures,of course, is always done afterthe beam is turned off. For anextra level of safety, Fermilabpolicy mandates that workersin radiological areas may onlybe exposed to levels that areless than one-third of theannual limit allowed by theDOE for radiological workers.As part of Fermilab’s careful monitoring program, theradiation detection “critters”keep a watch on radiation levelsthroughout the lab’s accelerator complex and beyond. Theorigin of the instrumentnames is often part of lab lore.In one legend, an employeeworking in frustration on aradiation instrument in the late1960s dubbed his instrumentthe “albatross,” alluding to thepoem The Rime of the AncientMariner and the sailor whowears an albatross around hisneck as a burden. The “scarecrow,” an instrument mountedon a tripod (left), would—if itdetected unacceptable levelsof radiation in an area—warnpeople to stay out of the area,like crows warned to stay outof a cornfield. A piece of hardware called the “aardvark”collects little, termite-like bitsof radiation data and has along, protruding trunk-line. The“chipmunk” makes a chirpingsound, and “hippos” are rotundand gray.The stories behind some ofthe names have been lost. The“pterodactyls”? “I really don’tknow how they were named,”says John Larson, team coleader. “But it’s a conversationstarter; it’s not boring. Youget tired of hearing acronymsall the time.”D. A. VentonLettersMore travel storiesReading the September issue of symmetry, I was reminded of when Larry Rosenson of MIT told methe story some years ago of being stuck on a long flight next to talkative woman. She insisted ontelling him how great her son was. “He did this, he did that .” Larry tried everything he could thinkof to stop her chatter. Finally, he took out a book titled something like “Elementary Particle Physics.”The woman saw the title and said, “Oh, I see you are studying elementary particle physics. My sonstudied advanced particle physics.”Harvey L. Lynch, Stanford Linear Accelerator CenterMake your own data cardThanks for the pictures of the pocket particle card [September issue]. I can’t wait to laminate thetwo halves together. Yes, you will be able to tell its a reproduction, but it still looks too cool!John Sandow, Harper College, IllinoisLetters can be submitted via letters@symmetrymagazine.org8

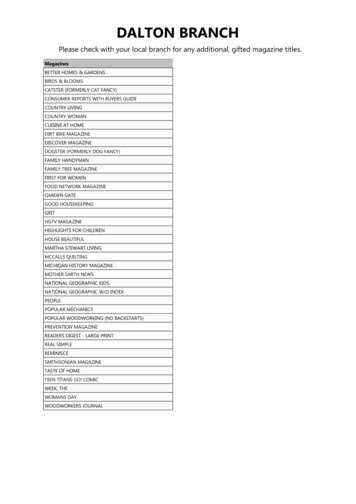

In the realm of the top-citedpapers in particle physics, life isindeed lonely at the top. Since1951, only 45 particle physicsresearch papers have climbedto the level of 2000 or morecitations; and of those 45, onlythree—for a ratio of one in 15—have reached the pinnacle of4000 or more citations.In fact, that last part of theclimb is the hardest of all. Thesecond-hardest step is gettingthe first 50 citations. The spiresdatabase lists some 235,000papers that have received fewerthan 50 citations; only 16,643crossed the threshold of 50,a ratio of one in 14. The ascentfrom 50 to 2000 was a relativelyeasy climb, with the ratio ranging from 1 in 1.8 (50 to 100 ) to1 in 4.7 (250 to 500 ).The three most highly-citedpapers are Steven Weinberg’s1967 “Model of Leptons” (Phys.Rev. Lett. 19 1264 (1967), 4602citations); Makoto Kobayashiand Toshihide Maskawa’s 1973“CP-Violation in the Renormalizable Theory of WeakInteraction” (Prog. Theor.Phys., Vol. 49 No. 2 (1973),2792 citations); and JuanMaldacena’s “Large N Limit ofSuperconformal FieldTheories and Supergravity”(Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2 231-Top-cited papers in HEPNumberofCitationssymmetry volume 03 issue 08/09 oct/nov 06Big jump needed tobe top-cited252 (1998), 4064 citations),which received all of its citationsin less than 8 years.Peak publication periods forpapers in the 2000 range are1998–99, with 12; and 1973–74,with seven. In 1998–99, the 12papers span a wide range ofinterests, from theoreticalpapers on strings and extradimensions (small and large), toexperimental papers on cosmology and neutrino oscillations.The 1973–74 period featured allseven top-cited papers on theory papers of the electroweakand strong interactions, whichlaid the groundwork for theStandard Model.Heath O’Connell, FermilabNumber of papersRatio4000 31out of 152000 451out of 3.41000 1511out of 4500 6121out of 3.3250 2,0351out of 4.7100 9,4941out of 1.850 16,6431out of 14up to 50235,000Papers with 2000 citationsJournal 7197281970NumberofPapers8

Fermilab shipping manager Claudie King. "We put it on the next flight." The greeting arrived on time and was presented to Eugenio Coccia, director of the Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso (photo). Like Fermilab's beamline, CNGS will help physicists understand the role that the puzzling neutrinos played in the early universe.

![The Symmetry and Crvsta] Structure Manganite, M (OH)O.](/img/62/zk95-163.jpg)