Transcription

Material quoted or reprinted from thispublication must be attributed to theAmerican Society of Internal Medicine.asimmamerican society of internal medicine2011 Pennsylvania Avenue, NWSuite 800Washington, DC 20006-1808(202) 835-2746Fax: (202) 835-0443

% 8.I-!2a :::::::::::::z.::.:.::::::::gkxgs4E-I s“0u:384::: 6

ExecutiveSummaryAs burgeoninghealth care costs havedriven employers and public health programs to turn increasingly to managedcare as a health care delivery method fortheir employees and beneficiaries, managed care’s use of board certification tocredential physicians has become an issue. The questions surrounding board certification affect all specialties. However,this paper presents the perspective of internal medicine, the nation’s largestmedical specialty and the specialty thatdelivers the majority of the medical careprovided to Medicare patients. TheAmerican Society of Internal Medicine(ASIM), an advocacy organization representing the interests of internists andtheir patients on matters of socioeconomichealth policy, has been charged by itsmembers with examining the many facets of the board certification debate.This paper addresses some of the keyquestions of the debate, including:What is board certification?Why is board certification becomingsuch a contentious subject in the context of managed care?What is the impact of the emphasisplaced on board certification by managed care plans?Why should board certification not beused as the sole criterion for credentialing physicians?Are there alternatives to board certification that will satisfy the public’s desire for guarantees of health plan physician quality, without adversely affecting high-quality, noncertified physicians?Two-thirds of all physicians in the UnitedStates are certified by one of the 24 members of the American Board of MedicalSpecialties (ABMS). Among ASIM’s members-whoare both generalists andsubspecialists-approximately 80 percentare board certified. However, some200,000 physicians nationwide are notboard certified. Many of those physicianswithout a board certificate are older physicians who entered medicine when boardcertification was not considered necessaryfor practice. The insistence by managedcare plans that their network doctorsmust be board certified not only fallsheaviest on physicians such as these buton the patients who have established relationships with them.A health plan that focuses solely on boardcertification as the test for whether it contracts with a physician may be overlooking a highly qualified, caring doctor whoparticipates in ongoing medical education, holds a teaching position at a medical school, or is an exceptionally empathetic yet cost-effective practitioner. Somehealth plans have begun to recognize theneed for alternatives to board certification in selecting high-quality physiciansfor their panels. In a recent survey of 62managed care plans, ASIM found 70 percent of those plans willing to accept otherstandards that would demonstrate solidperformance by a physician in the fieldof internal medicine.To assist health plans, policymakers andthe public in identifying alternatives toboard certification, this paper outlinesseveral measures that health plansshould consider to obtain a more accurateassessment of an internist’s clinical judgment and competence.

These measureslllllllllinclude:Meeting the training requirementsnecessary to sit for the certificationexamination of the American Board ofInternal Medicine (ABIM);Completionof an approvedmedicine residency;internalFaculty appointmentin a medicalschool or participation in teaching residents and medical students;Evidence of extensive continuing medical education (CME);Appointments to peer review or quality assurance committees;Evidence of a large, busy practicesatisfied patients;ofDocumentation of good standing in themedical community;Clinical privileges granted by a hospital medical staff, andOutcomesmeasures.It is not ASIM’s intent to dismiss boardcertification as an appropriate measureof a physician’scompetence.However,board certification as the sole measure fora physician’s selection by-andretentionin-a health plan will become more problematic as greater numbers of people receive their health care through managedcare. There are too many experienced,high-quality, but noncertified physiciansin the U. S. and too many patients withlong-standing attachments to those physicians to continue reliance on board certification alone.This document is one of four policy papers on “Reinventing Managed Care” published simultaneously by ASIM. The otherpapers, which are available on request,address methods for assessing physicianperformance,assuring appropriatepatient care under capitation arrangements,and access to subspecialty care.

troductionIn the last 20 years, managed care hasestablished a firm foothold in the UnitedStates as more businesses and publicagencies have chosen this method ofhealth care delivery for their employeesand beneficiaries. This managed care“revolution” has brought with it a host ofissues and dilemmas for patients, physicians, policymakers, purchasers andhealth plans.Somo issues of dobateare tbe managed careplans’ use of boardcertification as asurrogate for qualitymedical care, and theplans’ insistence thattheir physicians beboard certified.Some issues of debate are the managedcare plans’use of board certification as asurrogate for quality medical care, andthe plans’insistence that their physiciansbe board certified. Although the boardcertification issue affects many medicalspecialties, this paper generally reflectsthe perspective of internal medicine, thelargest medical specialty in the UnitedStates. The American Society of InternalMedicine (ASIM), an advocacy organization representing the interests of internists and their patients on matters of socioeconomic health policy, has beencharged by its members to examine themany facets of the board certification debate. Some of the questions this paperaddresses are:What is board certification?How many physicians are board certified?Why is board certification such a contentious issue in the context of managed care?This white paper also discusses severalalternatives to board certification thatwould satisfy the public’s desire for guarantees of quality medical care from healthplan physicians. These alternatives wouldhave no adverse effect on noncertifiedphysicians who provide high-quality care:WhatIsBoardCertification?There are 24 medical specialty boards inthe U. S. representing certain core disciplines of medicine such as internal medicine, family practice, ophthalmology, psychiatry, surgery and radiology. Most of the24 boards-which are all members of theAmerican Board of Medical Specialties(ABMSGalso award certificates in theirsubspecialties. The ABMS is made up ofrepresentatives from the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Hospital Association (AI-IA), the Associationof American Medical Colleges (AAMC),and the Federation of State MedicalBoards. Today, over 60 percent of all physicians are certified by one of the ABMSb0ards.l While board certification is voluntary on the part of a physician, it isbecoming increasingly difficult for doctorsto practice without this designation.The American Board of Internal Medicine(ABIM) was established 60 years ago withthe aim of enhancing the knowledge,skills and quality of care provided by doctors of internal medicine. Not a part ofor affiliated with-any organization otherthan ABMS, the ABIM neither confersprivileges to practice medicine, nor is certification by ABIM required to practicemedicine. As stated in its Policies andProcedures for Certification: “The Boarddoes not intend either to interfere withor to restrict the professional activities ofa licensed physician because the physician is not certified.“2ABIM certification includes several com-

ponents, of which the board examinationis the most well-known.This writtenexam is intended to “provide evidencethat a diplomate’s fund of medical knowledge is both comprehensiveand up-todate.“3 Physicians certified prior to 1990hold certificatesthat are valid indefinitely, but those who took the examination after 1990 must take it again every10 years to retain their board-certifiedstatus. Diplomates with certificates issued before 1990 also will be given thesame opportunity to recertify, by takingan at-home, open-book self-test; undergoing an evaluation of credentials; and taking a proctored final exam. The ABIM setstraining requirements for candidates forthe board exam, evaluates their credentials, substantiates their “clinical competence and professionalstanding,” anddevelops and conducts the examinationfor certification and recertification.4To sit for the ABIM exam, which is givenannually throughoutthe U.S., PuertoRico and Canada, physicians must havegraduatedfrom an approved medicalschool, completed three years of accredited trainingafter earning their MD(medical doctor) or DO (doctor of osteopathy) degree, and must substantiate to theABIM competence in “clinical judgment,medical knowledge, clinical skills (medical interviewing,physical examination,and procedural skills), humanistic qualities, professionalism,and provision ofmedical care.“5 The ABIM has set guidelines for a minimum number of times acandidate must perform certain diagnostic and therapeutic procedures to be eligible for certification. In addition, physicians must pay ABIM an exam fee of 790.6When a candidate for internal medicineboard certification receives notice of admission to an exam, he or she achieves astatus known as “board eligible.” Essentially, this means that the candidate hasfinished the necessary training, demonstrated appropriate clinical competence,and has met other credentialing requirements, except for passing the exam.In the past, physicians had up to six yearsor four attempts to take the exam beforetheir board eligibility expired. They couldrenew their board eligibility by meetinga complicated set of requirements set outby the ABIM-suchas demonstration ofsatisfactoryclinicalcompetenceandcompletionof 100 hours of continuingmedical education (CME) in two years,and passing a “qualifying” exam. However, in July 1995, ABIM officials informed ASIM that they had begun a complete review of policies concerning theboard-eligible status. ABIM plans to announce these revised policies by Dec. 31,1996. In the meantime,all currentlyboard-eligible candidates will remain eligible and able to sit for the certifyingexam in internal medicine, the subspecialties or areas of added qualifications.Thirty years ago, boardcertification wasviewed as a fulfill !nlof a personal goal,DemographicsofBoardCertificationTwo-thirds of all physicians nationwideare board certified. However, another200,000 are not.7 A report on the makeupof the U. S. physician population from1980 to 1986 found that, while the totalnumber of physicians increased, the percentage of those who were board certifieddid not increase proportionately. Callingthis a “major finding,” the authors notedthis meant that a “progressively growingnumber of physiciansare therefore inpractice without this criterion of postgraduate educational achievement.“snot as a necessaryprofessional credential.

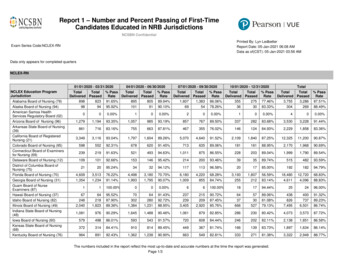

Many physicians who are not board certified entered medicine when certificationwas used more by academic consultantsthan by physicians in private practice.gThirty years ago, board certification wasviewed as a fulfillment of a personal goal,not as a necessary professional credential. Before 1972, the certification processincluded an oral exam as well as a written test. This oral exam was consideredby many physicians to be subjective, withthe results depending “more on what theexaminer had for breakfast than theexaminee’s competency.“‘O AlthoughABIM discontinued the oral part of thecertification program in 1972, quite a fewphysicians who went through the processvowed never to repeat the experience.Accrdin! to fifJlll’O!lcompiled by tbe AMA,55 percent of allpracticing primarycare physiciansIn tbe U. 8. areboard certltied.According to figures compiled by theAMA, 55 percent of all practicing primarycare physicians in the U. S. are board certifled.ll The total number of U.S. physicians qualified by training to call themselves internists is 113,970. Of those,58,576 designate themselves as generalinternists. Of these self-designated general internists, 42,240-slightly over 72percent-are board certified.In 1989, ABIM granted board-eligible status to some noncertified internists whohad taken the exam at least once, affecting approximately 15,000 internists.12 Ifthese individuals do not pass the boardexam, their eligibility will expire in 1996.in their employee health benefits plansincreasingly turned to managed care, andas more people found themselves limitedby those plans to network providers, theclamor grew for “proof’ that those providers delivered “high quality care.” Outcomes measures and other scientificallybased standards of what constitutes“quality” care were too new and untested,as well as too difficult for many purchasers to understand. So health plans beganemphasizing the credentials of their network physicians and their accreditationby organizations such as the NationalCommitteefor Quality Assurance(NCQA). NCQA accredits managed careplans throughout the U.S., and has approved about half the health maintenanceorganizations (HMOs) in this country. AsLee Newcomer, MD, national medical director for United Healthcare Corporation,said at a managed care conference sponsored by ASIM in 1994, “I will tell youthere is no objective evidence that boardcertified physicians are better, but thebottom line is that the people who buyour coverage want board-certified physicians and, therefore, so do we.“13In a 1993 article advising its readers“How To Size Up a Doctor Network,”Money magazine outlined five questionsprospective enrollees should ask about amanaged care plan, including: ‘What percent of the plan’s doctors are board certified?” The magazine then went on to suggest that a 70 percent board certificationrate, “about average for [HMOsl and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) isacceptable. Also make sure the board thatcertifies your doctor is one of the 24 recognized by [ABMSI he importance of board certification for According to a 1994 survey of managedphysicians has risen in tandem with thegrowth of managed care. In the last decade, employers looking to restrain costscare plans conducted by the Group HealthAssociation of America (GHAN), 85 percent of physicians who provided services

under an arrangement with a managedcare plan were board certified. In 1992, aGHAA survey of managed care plansfound 70 percent considered board certification “very important” in their selection of physicians (medical liability history and hospital privileges did, however,score higher) while only 1 percent saidthis credential was not a factor.15The Physician Payment Review Commission (PPRC) also conducted an extensivesurvey of managed care plans in 1994.The PPRC found that 57 percent of the108 responding plans required physiciansto be board certified or board eligible.Most of the group or staff model HMOsquestioned in the survey required boardcertification, while “a smaller proportionof other types of plans” did so.16That same year, ASIM surveyed over 60HMOs around the country and learnedthat only 10 percent required certificationby one of the ABMS boards as a minimumacceptance standard. However, 74 percent said certification was “strongly preferred,” although they made exceptionsin rare cases. Asked their reasons for emphasizing board certification, almost60 percent of the plans cited employers’and patients’ desires for board-certifiedphysicians and also noted that NCQAlooks at the percentage of board-certifiedphysicians in a plan as one of its evaluation criteria. Among plans that requiredor strongly preferred board certification,27 percent mentioned marketing advantages, 30 percent said employers and patients wanted board-certified physicians,and 28 percent said that NCQA and otherregulators were looking at the percentage of board-certified physicians.As these survey responses show, NCQAand its rating system have figured prominently in the board certification debate.NCQA requires plans to have “rigorous”credentialing and recredentialing procedures. Although hospital privileges andwork and malpractice history are factorsNCQA requires plans to investigate, itdoes not prohibit plans from using boardcertification as a prerequisite for selection.ls NCQA creates report cards onhealth plans using a system called theHealthplan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS). Among the elementsHEDIS uses to measure plans is the percentage of board-certified physicians inthe plan. The higher the percentage, thegreater the likelihood that the plan willbe viewed as delivering “high quality”care, which, in turn, will aid in its marketing strategy.In addition, many states are consideringproposals to link board certification tolicensure, and a number of HMOs havebegun to use certification as “a quick,clean cut when they need to reduce theirphysician panels,” according to PeterKongstvedt, MD, a former HMO president who is now a consultant with theaccounting firm Ernst and Young.la Kaiser Permanente, the largest HMO in thecountry, requires physicians to becomeboard certified within three years of being hired by the company.TbeAmericenHespitalAsseciatiensurveyed Itsmen8lersin1882and ieund tbei85perceni wererequiringBeyond the managed care world, evensome hospitals are using board certification as a requirement for privileges. TheAmerican Hospital Association surveyedits members in 1992 and found that 95percent were requiring new doctors seeking privileges to be certified. A number ofother hospitals were requiring board certification for physicians to renew theirprivileges.ls This last development couldpose a problem for the hospitals themselves, however, if they receive any Medicare funding, since the program’s regulations specifically prohibit hospitals fromnewdectersseeking privilegestebe certliied.

Fusing certification as the sole criterion forgranting staff membership or e’EmphasissonBoardCertification?wllle currf!alalternatives forphysicians witboula board certificateare limited.hat has been, and what will be, the effect of managed care plans’ use of boardcertification for entrance into their provider networks?In a 1993 letter to theNew England Journal of Medicine, thecurrent speaker of the MassachusettsMedical Society’s House of Delegates citedstatistics compiled by the state medicalsociety showing that nearly 1,200 Massachusetts doctors were not board certified. In some cases, these physiciansstarted practice before their specialtyadopted board certification.In othercases, “many physicians did not becomecertified, because doing so was not considered important for private practice. Asthat correspondent correctly noted, exclusion of over 1,000 physicians providingprimary care “will exacerbate problemsof access for patients, and at the sametime deprive many competent, experienced physiciansof their livelihoods.What is needed is a change in credentialing criteria that reflects the value of thesame or similar training followed by multiple years of practice experience and recognized competency in clinical practice.“20Some leaders of medicine have warnedthat the medical community could “playthe economic game” and give all physicians board certification upon graduation.This would devalue board certificationwithout providing any useful alternativeto identify high-quality physicians.21In order to claim that they are “board certified,” some physicians are using designations given by groups other than theABMS boards. This only confuses patients and employers trying to ascertainthe caliber of providers associated withtheir health plan. Only three statesCalifornia,Florida and Colorado-barphysicians who have become “certified”by self-designatedboards from callingthemselves “board certified.” Challengesto such laws are arising from those whocontend that the ABMS does not reflectthe emerging multidisciplinaryapproachto health care and medicine. The executive director of the American Academy ofPain Management,a self-designatedboard in California, has said: “It’s an economic guild issue. .The public should beallowed to make its own informed decisions about specialists. . .ABMS has noacupuncture board, no herbalist board.When 1 out of every 3 is spent on alternative medicine, it would indicate thatthe ABMS is missing the boat.“22Contributingto this confusion are the“certificatesof added qualification”invarious subdisciplines, offered by severalABMS members. For example, ABIM andthe American Board of Family Practicehave established a certificate of addedqualification in geriatric medicine. Thesecertificates do not represent full-fledgedboard certification, but they are nonetheless legitimate credentials issued by thosespecialty boards.The current alternatives for physicianswithout a board certificate are limited.Some physicians could base their practices solely on Medicare since that program does not require board certificationto participate. However, as changes aremade in Medicare program reimbursement, this will be increasingly untenablefor most physicians. Noncertified physi-

cians could always join a group practicecomprising mostly board-certified physicians. Yet, if the proportion of nonboardedphysicians in such a group becomes toogreat, managed care plans could becomereluctant to contract with the group forfear that it would affect their NCQA rating. Physicians also could try to get theirpatients who are enrolled in a managedcare plan to lobby for their inclusion inthat plan. Another option would be forphysicians to arm themselves with dataabout the cost-effectivenessof their services despite a lack of board certification.Dr. Newcomer cautions that, in compiling profiling data, a physician’s “perception of ‘best’ may be different from thatof the plan.“23 Finally, physicians canbecome board certified. However, thismay be more feasible for physicians whohave completed a residency and are stillwithin their specialty’s time limit for taking the test.Physicians personally feel the burden ofthe heavy emphasis placed on board certification by managed care plans. A letter to ASIM from one of its members illustrates this. After graduating from ahighly rated medical school in the early1960s completing his residency, servingas president of his local medical societyand state society of internal medicine,teaching as a clinical instructor,andbuilding and maintaining a thriving practice for almost 30 years, this member didnot pass the board certification exam. Hewrote that his colleagues told him, “Don’tworry, look around, it’s just a club.to addstatus to [those who passed the exam] asconsultants.” Although by all other measures this physician had enjoyed a successful career, the growing emphasisplaced on board certification made himfeel “second class.” Eventually, he closedhis practice and moved to a rural area“where I’m closer to the patient and fur-ther from that oppressive potentialstriction-notboard certified.“24re-In sum, there are many reasons why fullyqualified physicians may not have takenthe board exam. The burden of proof forboard certification requirements shouldfall on those who insist that well-qualified physicians must take and pass theexam in order to provide patient astheSoleCriterionforPhysicianSelectionReducing the emphasishealth plansplace on board certification as the minimum acceptance requirement will be difficult because the plans continue to sensethat patients and employer-purchaserswant some concrete assurance that theirphysicians meet a certain level of quality. However, the use of board certification as the sole criterion for selection to aplan is being challenged more and more.Even NCQA officials caution against using the percentage of board-certified physicians as a deciding factor for whetheran employer or patient should choose aplan. Last year, in an issue of ManagedCure, Janet Corrigan, executive directorof NCQA, said of the HEDIS measurement of the percentage of board-certifiedphysicians in a plan, “It’s one of many,many indicators in the HEDIS process,and it’s intended to be used in that context. We wouldn’t expect any one indicator to be a deciding factor for any of theoutside organizations that might be reviewing HEDIS information.“25Tbeburden of prooffor board certificationreqoiremeafs shouldfall on those who insistfkaf well-qoalifledphysicians must fakeaad pass the exam Inorder to providepatient care.

As noted earlier, board certification requirements may fall heaviest on older,experienced physicians. But managedcare guidelines calling for board-certifieddoctors can work a hardship not only onolder physicians but also on younger ones.Eight of the 24 medical specialty boardsrequire a young physician to satisfy certain practice qualifications before gaining eligibility for the exam. If health plansexclude these young physicians, not onlyis this an unjust prejudice against young,well-qualified, competent doctors, but italso could affect Medicare beneficiaries’access to physicians. A recent PPRC report noted that, although the number ofdoctors who began seeing Medicare patients from 1991 to 1993 outnumberedthose who stopped seeing such patients,these new physicians were “younger andwere less likely to be board certified thanwere those who stopped seeing Medicarepatients.“26 As more Medicare beneficiaries receive care under managed care, thisbecomes a b acteristicsthatmay be extremelybnpwtanttopatients.While health plans contend that purchasers and patients want board-certifiedphysicians because these doctors offerhigher quality care, there are few studies validating this. One study that attempted to answer the question, “Doesboard certification mean high quality?”looked at 259 internists, of whom 185were ABIM-certified. It found a “clinicallymodest trend suggesting that board-certified physicians provided more comprehensive preventive care compared tononcertified internists.“27 Even so, thestudy also found “more similarities thandifferences” between ABIM-certified andnoncertified internists on questions ofpractice patterns, patient satisfaction,and patient outcomes.2s Given the inconclusive and minimal objective data, further study on the relationship betweenboard certification and quality might bedesirable before health plans use boardcertification as a definition for quality.Board certification does not guaranteephysician characteristics that may beextremely important to patients, such aslistening ability, time spent with a patient, availability when a patient is sickor facing an emergency, and the length ofthe physician-patient relationship. Neither does it measure “the ethical natureof a physician’s practice; the value of lifeexperience; the ability of a physician toparticipate as part of a health care team;practice performance through a peer review process; or the devotion and satisfaction of patients.” Nor can the exammeasure “motivation, adaptability, workhabits, response to criticism, and handling of stressful situations.“2g Board certification only reveals what “a doctorknew at a particular point in time, andcannot measure what has been learnedor forgotten in the interim,” according towitnesses at a 1994 PPRC hearing.30Many areas of the country are currentlyexperiencing severe shortages of physicians. In these regions, board certificationacts as an impediment to a community’sability to find qualified doctors. Becauseof this, some health plans have loosenedtheir physician selection requirements inunderserved areas. For example, UnitedHealthCare will accept three years ofpostgraduate residency training in lieu ofcertification in areas with few boardedphysicians.31Health plans that insist on board certification may be turning away nonboardedphysicians who have participated in ongoing medical education, have held teaching appointments at medical schools, andhave taken other steps to keep their medical knowledge current. There is a greatdeal of debate within internal medicine

over the equity of the present policy thatpermanentlycertifies physicianswhopassed the exam before 1990. Physicianswho passed the board years ago may, infact, be less knowledgeablethan newer,noncertified practitioners. Indeed, a 1991study found that internists’ knowledgebase declined significantly after 15 yearshad elapsed since passing the board certification exam.32Some health plans, recognizing the limitations of board certification, have begunto broaden their criteria for selecting physicians. United Health Plans of New England instituted a policy five years agothat all physicians at the time of application would have to be board certified orobtain certificationwithin five years.Nonboarded physicians in the plan were“grandfathered” in. After the five yearshad elapsed, the health plan revisited itspolicy because some of its physicians hadnot become certified. In a letter to ASIM,the medical director of United HealthPlans stated, “We recognized that some,if not all, of the physicians who had notobtained board certification within thefive-year period appeared to be, by anyother available subjective or objectivemeasure, excellent physicians. Thus, weamended our credentialing plan to allowmore flexibility in granting exceptions tothe board certification requirement forphysicians who are board eligible on entry, but who do not receive certificationwithin the all

The questions surrounding board cer- tification affect all specialties. However, this paper presents the perspective of in- ternal medicine, the nation' s largest . When a candidate for internal medicine board certification receives notice of ad- mission to an exam, he or she achieves a status known as "board eligible." Essen- tially .