Transcription

An Exploration of Emotion and CognitionAn Exploration of Emotion and Cognition during PolygraphTestingJasmine Khan1, Ray Nelson2 and Mark Handler3“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”--W. Shakespeare, HamletAbstractThe fight-flight, or fear, response is often the focus of attention when examining the role of emotionin the psychophysiological detection of deception (PDD, polygraph) setting. This paper asserts thatrather than fear alone, many other emotions may play a role during PDD.We go further toexamine the relationship between cognition (appraisal) and emotions. Although there remains noconsensus in the exact mechanism of this relationship, most research has identified at least twodistinct patterns, or levels, of appraisal: subconscious and conscious awareness. Both levels ofappraisal trigger emotions. We have also seen that the specific emotion triggered can vary widelyamong individuals based on their prior experiences, values, goals, and expectations and mostimportantly, how the situation is appraised.Cognitive appraisal plays a significant role in triggering emotion and physiological reactions. Thesereactions must be interpreted with caution as it is not clear which emotion has evoked whichpattern of response. Although there is no doubt that there are physiological changes thataccompany emotion, we are yet unable to distinguish specific emotions using PDD technology.somatomotor center changes (Janig, 2006)have often been overlooked. This paper asks1) How important is cognitive appraisal intriggering emotion? 2) Are the changes inANS arousal and presumed hypothalamicmediated somatomotor center changes in thePDD setting due to fear, another emotion, or acombination of emotions? 3) Can the PDDcharts distinguish between specific emotions?4) What does all this mean for cal Detection of Deception (PDD)examination are grounded in the psychophysiologicalscienceswiththewellestablished “fight-flight” response being afoundational tenet.However, the role ofcognition and appraisal in triggering anautonomic nervous system (ANS) responseandputativehypothalamicmediated1Jasmine Khan, PhD, LPC, LSOTP, is a private practice therapist who has treated sexual offenders for over 10years. She is also an adjunct faculty member of Baylor University.2Raymond Nelson is the developer of OSS-3, a private practice examiner and a regular contributor to the journalPolygraph .3Mark Handler is a former law enforcement examiner, the Research and Information Chairperson for the AmericanAssociation of Police Polygraphists, and a regular contributor to the journal Polygraph.Authors’ Note: The authors are grateful to Barry Cushman, Chuck Slupski, Leonard Salcedo, Elmer Criswell, TobyMcSwain, Don Krapohl, Dr. Stu Senter, Dr. Tim Weber and Dr. Charles Honts for their thoughtful reviews and/orcomments to earlier drafts of this paper. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors, and donot necessarily represent those of the American Association of Police Polygraphists or the American PolygraphAssociation. The authors and the APA grant unlimited reproduction rights to any polygraph school accredited bythe AAPP or APA. Questions and comments are welcome at Jkhan@Grandecom.net, polygraphmark@gmail.com,and raymond.nelson@gmail.com.Polygraph, 2009, 38(3)184

Khan, Nelson, HandlerAlthough there is no universalagreement on the definition of emotion we willuse the term to refer to the consciousexperiences and physiological changes thatoccur in response to external or internalstimuli. Emotions have three components:physical arousal, behavioral manifestationand inner awareness of the feeling. Cognitionrefers to the conscious or subconsciousmental processing of information to acquire,process and store knowledge. This includesappraisal of situations and circumstances todetermine appropriate response.Cognitionand emotion are intricately intertwined.Although different theoretical perspectives willdisagree as to the precise relationship betweenemotion and cognition and how they combineto influence ANS arousal and commonlysuggested hypothalamic mediated somatomotor center changes, it can be agreed thateach plays a significant role.avoidance based conflict. The updated theoryseparated pure “freeze”, which is typicallyassociated with the fight or flight response,from those that were behaviorally inhibited.This introduced the concept of higher brainfunctions being able to override programmedbehavior as such adaptive capabilities wouldserve to expand a response repertoire that canincrease the chance for survival.The biological function of emotions isto prepare the organism for a reaction, oftenin the form of a physical action, even though areaction may not be needed and may notoccur. Emotions, however, allow a head starttowards a reaction. There are a number ofphysiologicalchangesthatoccurinanticipation of a potential negative encounter.This feed-forward type of physiologicalpreparation is referred to as allostasis(Handler, Rovner & Nelson, 2008). Allostasiscan be described as a central nervous systemmediated, integrated brain-body responsegeared towards viability or survival. It occursin regulatory systems which have no fixed setpoint and all are the result of evolutionarytinkering.Purpose of EmotionsEmotions are the result of evolutionaryfine-tuning that is intended to ensure thesurvival of an organism. Emotions haveessentially one primary purpose. Emotionsprepare an organism for reaction (Ekman &Davidson, 1994; Lazarus, 1991). Emotionscan be seen as tools that regulate behavior inrelation to patterns laid down throughevolution.1) How important is cognitive appraisal intriggering emotions?A brief overview of prevailing theoriesis warranted to understand the intricaterelationship that cognition plays in triggeringemotion and therefore the physiologicalresponse. One of the earliest modern theoriesis the James-Lange Theory of Emotion whichstates that when presented with stimuli theANS automatically responds with physicalchanges. When the individual becomes awareof these physical changes they label theiremotions.For example, a person sees asnake, her heart starts beating fast, shebecomes aware of her bodily changes andrealize “My heart is beating hard therefore Iam afraid” (James, 1884; Lange, 1885). TheJames-Lange theory states that consciousawareness of the emotion occurs after the ANSresponse. The role of cognitive appraisal ofthe stimulus is not a component in thismodel.Cannon (1927) described fear reactionsas an overall sympathetic nervous system(SNS) arousal resulting behaviorally in whathe called fight-or-flight. When presented withan emergency situation, Cannon believed theanimal can choose to fight the danger orattempt to flee. Fighting and running awayboth involve an initiation of movement,whereas immobility, another behavioral optionsuggested by Gray (1988), is just the opposite.Gray (1988) introduced the term BehavioralInhibition System (BIS) to describe a series ofresponses to fear stimuli that include;increased arousal, behavioral inhibition, andincreased attention. The freeze responsebecame an integral part of Gray’s early BIShypothesis and describes an inhibition ofongoing behavior. Updated descriptions of theBIS by Gray and McNaughton (2003)characterizedbehavioralinhibitionasdecreased motor activity when presented withfear or anxiety associated with an approach-In the following decades the CannonBard Theory of Emotion described the ANSresponse and experience of emotion asoccurring simultaneously (Cannon, 1927;185Polygraph, 2009, 38(3)

An Exploration of Emotion and CognitionBard, 1934). Cannon-Bard theory states thatwhen presented with stimuli, sensory data isprocessed by the brain (thalamus) andsimultaneously sent to the organs of thenervous system and cortex.that the role of cognition and appraisal of thestimulus is significant in the process.Robert Zajonc (1984) supports theJames-Lange theory and described anexposure effect and wrote that some emotionalreactions can bypass the cognitive appraisaland trigger an immediate ANS response. Incontrast, Richard Lazarus’ cognitive mediationtheory (1984) reports that we must cognitivelyattend to our physiological response in orderto ascertain our emotion. See Table 1 belowfor a comparison of the major theories ofemotion.In the 1960’s Schacter and Singer(1962) asserted that cognitive appraisal playsa key role in the experience of emotion. Forexample, when exposed to a snake, a personwill interpret the snake as a threat andsimultaneously the ANS will be aroused. Thesecond response will be the consciousawareness of fear. This model is radicallydifferent from previously proposed models inTable 1. Theories of EmotionTheoryJames-LangeStimulusSnakeInitial responseANS arousalCannon-BardSnakeSensory Processing bythe ThalamusSchachterSinger twofactor theorySnakeCognitive appraisalANS arousalZajoncExposure effectLazarusCognitiveMediationTheorySnakeANS arousalSnakeCognitive appraisal(“this is a threat”)Feel fearModern theorists use the ZajoncLazarus debate (Buck, 2000) as an example ofhow semantics and definitions can producedifferent theories of emotion. At contest inthis debate was whether a subject couldrespond to a stimulus subconsciously,without knowing what it was. Zajonc (1984)argued that a person could respondemotionally independent of cognition, and thatcognition requires mental work or evaluationof a stimulus.Zajonc held that whenPolygraph, 2009, 38(3)Secondary responseInterpretation of ANSreaction. Consciousawareness of fear. (“Myheart is beating hard, so Imust be afraid”)ANS arousalConscious awareness offear (“My heart is beatinghard and I am afraid”)Conscious awareness offear (“The snake couldharm me and I am afraid ofit”)ANS responseemotional responses occurred subconsciously,they occurred in the absence of cognition.Lazarus (1984), on the other hand, arguedthat cognition occurs in concert with anyprimitive evaluative perception.For ourpurposes, we will accept an integrativeassumption that both are correct, and thatcognition includes both early and lateresponses as illustrated by the work ofLeDoux (1996) in the area of conditioned fear.LeDoux found strong evidence for two neural186

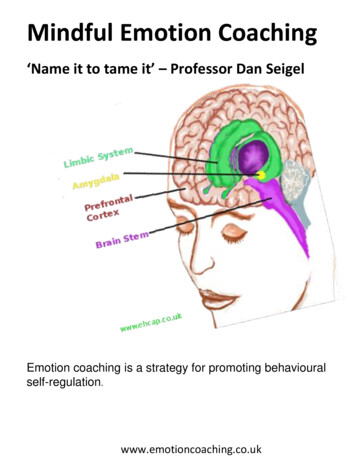

Khan, Nelson, Handlerpaths of activation for conditioned fear in rats.Information from external stimuli may reachthe amygdala via the sensory thalamus (lowroad) while a second path was routed throughthe sensory cortex (high road). Several nucleiwithin the amygdala are responsible foractivating a number of fear responses. Thelow road path provides a “quick and dirty”warning while the high road path allows forslower but more accurate assessment of thestimulus (LeDoux, cal and outcome data is assessed. Itis this secondary appraisal that can trigger alarge variety of emotions in individuals due todifferentexperiences,perceptionsandmeaning assigned to the initial stimuli. Thisbecomes relevant for the polygraph examiner.Intertwined with the concept of autoappraisalis the process of classical conditioning. If afearful stimulus has been experienced in thepast and resulted in a negative consequence,a conditioned response can occur when theindividual is exposed to that stimuli, similarstimuli or even unrelated stimuli thatoccurred at the same time as the originalevent.As is frequent in the evolution oftheories, as new information and newtechnology become available for examining theprocess of emotion emerge, new perspectivesdevelop. Rather than dismiss any early theoryas being right or wrong, it would be moreaccurate to state they were incomplete. Wemay still only know a small part of the processbut understanding is improving. Ekman’scurrent ideas on the process of emotionencompass many of the previous theoreticalperspectives.Ekman (2003) presents theconceptofautoappraisalthatoccursinstantaneously when a sudden threat arises.We will use a common example of driving. Acar suddenly heads toward you and will hityou if no action is taken. You swerve andmiss the vehicle. All this may happen in lessthan a second. What process took place?Your sensory registers (eyes) saw theoncoming car. This information was sent tothe brain which in turn instantly appraisedthe situation as being imminently dangerousand needing action. The brain triggered thearousal of the ANS and the body was able tocoordinate action to avoid the threat. Withinseconds we apply conscious appraisal to thesituation and may acknowledge feeling fear orother emotions. The autoappraisal can occurat a subconscious level and is so rapid thatearly theorists assumed there was no time forcognitive intervention to be occurring. Ekmanand others (such as Roseman, 1984) believethat there has to be some form of initialappraisal that triggers the ANS system toaction.Additional conscious cognitiveappraisal occurs after the ANS response. Itwould seem that cognitive appraisal may haveseveral roles in the triggering of emotion. Theinitialautoappraisalorsubconsciousappraisal that is the initial trigger forphysiological response and a secondaryconscious appraisal occurs beyond the initialreactions.During this secondary, orDuring PDD testing, examinees arepresented with a number of stimuli, in theform of test questions, and are essentiallyasked to attend to each sequentially.Presumably, as the examinee attends to eachtest question they conduct an appraisal withrespect to what that test question means tothem. This appraisal relates to the examinee'sgoals and how those goals may be affectedwithin the PDD setting.Cognition andappraisal are a process of evaluating astimulus for goal congruence within theexaminee's motivational framework. While it isnot feasible to attempt to state we know whatparticularmeaningagivenexamineeattributes to an individual test question, it ispossible to discuss a number of possibilities ofwhat the examinee could be thinking in termsof goal congruence. Appraisals are simply anevaluation and then assignment of emotionalmeaning, value or salience (Power & Dalgleish,2008; Scherer, 2000).In the usual diagnostic PDD setting wecan typically assume that the goal of theexaminee is to maintain freedom and beviewed as innocent of accusations. Thesegoals have high relevance to most individuals,and the PDD examination and potentialoutcome can be highly incongruent withachieving these goals. Ego-involvement is alsohigh due to the extreme personal implicationsregarding ones identity and self-esteem shouldresults of the PDD threaten the publicpersona. We have suggested that emotionsare the response to appraisals of thesignificance of a given situation with respectto goals. We offer there are two routes ofappraisal through which emotions may occur187Polygraph, 2009, 38(3)

An Exploration of Emotion and Cognitionand both are applicable to PDD testing. Bothroutes of appraisal involve a cognitivecomponent and are equally capable of elicitingan emotion.One route is a conceptual,computational or schematic route and theother is a reinstatement of a previouslylearned or evaluated situation (Power &Dalgleish, 2008). The former will be developedor computed through a situational analysis.The latter relies on memory of an earlierresponse and produces a faster, thoughpotentially less accurate response. In eithercase a situation that is appraised as havingsignificance for a person's goals can elicit anemotional reaction either as a result of areinstated prior emotion or because theperson has perceived the situation to be onethat will affect their goals.some anxiety or even fear surrounding thethought of not getting the job or being labeledas someone who is not qualified for the job,thus ending his law-enforcement career.Some of these emotions could have occurredbecause during the appraisal process, theexaminee became concerned that his past actsare incongruent with the goal of obtaining thejob. Other emotions could result from resociallyobjectionable.This is just one possibleexample of the multitude of ways theexaminee could use a bottom-up orconstructive approach to generate emotionalstates.A PDD related example of a conceptual,computation or schematic route forgenerating an emotional state.2) Are the changes in ANS arousal andhypothalamic mediated somatomotorcenter changes in the PDD setting due tofear, another emotion, or a combination ofemotions?This route of appraisal describes onethat is essentially pieced together in aconceptual or story-like manner. In this casethe appraisal is being conducted as the piecesof information become available. For exampletake an examinee in a public safety preemployment screening polygraph test that hasbeen less than forthcoming about his pastcriminal activities.During his pre-testdiscussions of these issues he silentlycompares his personal involvement in criminalactivities against what he believes are societalnorms or what the hiring agency will accept.He concludes that telling the complete truthabout what he has done may be incompatiblewith the hiring preferences of the agency towhich he has applied. He may believe that inorder to continue in the hiring process hemust lie about these acts or minimize hisadmissions.This requisite deception maythen result in the activation of one or moreemotions, which are in response to anappraisal. Perhaps the examinee is angrywith himself for having done these things,considering them stupid.Alternatively hecould be angry with the hiring agency forinquiring into what he feels is a private matteror one that may have happened long ago. Hemay feel some level of guilt for what he hasdone or possibly experience some degree ofshame or embarrassment at the prospect ofthe polygraph examiner and hiring agencydiscovering this issue. There may also beThe existence of basic emotions, thatis, a universal set of emotions that arecommon to all humans has been debated byresearchers of emotions for centuries.Itseems that the concept of a basic emotion, forexample, anger, may in fact comprise of arange or family of emotions (Ekman, 2003).So rather than consider each of the basicemotions as a single affective experience, itmay be more helpful and accurate to considereach basic emotion as a family or cluster ofrelated emotions. There is a moderate degreeof consensus that a small set of emotions canbe considered basic or universal (Ekman,1992). These basic emotions are anger, fear,disgust, surprise, happiness and sadness.Several researchers (Power and Dalgleish,2008) point out that surprise does not alwaysresult in an emotion, and have dropped itfrom the list.Since surprise is notindisputably an emotion state and is not anaffect state we would want to produce duringa PDD test, we will follow the recommendationof a number of emotion researchers and dropit from the list of what we consider "basicemotions".That leaves us with thoseemotions that are listed in Table 2 along withtheir accompanying appraisals. These fewemotions have been identified to play anessential role in daily survival, such asescaping from harm (fear), avoiding toxic food(disgust),andpursuingreproductiveendeavors (happiness).Polygraph, 2009, 38(3)188

Khan, Nelson, HandlerTable 2. The key appraisals for each of the five basic emotions, adapted fromPower and Dalgleish (2008).Basic tion or perceived blocking of a roleor a goal, directed at the perceivedthwarting agentPhysical or social threat to self or goalDisgustSomething repulsive to oneself or society.SadnessActual or potential loss or failure of avalued personal role or goal.HappinessPositive move towards a valued personalgoal or role.As presented in Table 2 the appraisalsthat trigger anger relate to the real orperceived blocking of a significant goal or rolerelevant to the individual. In the PDD settingthe examiner or the questions being asked canbe perceived as being an obstacle towardmaintaining goals. Fear and anxiety, similarlyare triggered by the appraisal that there is athreat to oneself or one’s goals. Again thePDD examiner or the questions asked mayelicit this appraisal.between ANS response and emotion and hasprovided the most convincing evidence to datethat ANS activity is emotion-specific.Several studies have attempted to finddifferences in autonomic nervous system(ANS) arousals. Sinha, Lovallo and Parsons(1992) found systemic differences amongemotions which have negative valence. Angerresulted in greater diastolic blood pressureand increased peripheral resistance whencompared to fear. Levenson, Ekman andFriesen (1990) compared anger and fear usingfinger temperature and reported an increasein temperature for anger and a decrease forfear. Cacioppo, Petty, Losch and Kim, (1986)reportedincreasedelectromyographicactivation of corrugator muscles duringnegative affect stimuli and greater activationof zygomatic activity with positive affectstimuli. Levenson, et al (1990) reported thefinding of four reliable differences among thenegative affect emotions of fear, anger,sadness and disgust. They found: (a) angerproduced a greater increase in heart ratewhen compared to disgust; (b) anger produceda greater increase in finger temperature whencompared to fear; (c) fear produced a greaterincrease in heart rate when compared todisgust and (d) sadness produced a greaterincrease in heart rate when compared todisgust.3) Can PDD charts distinguish betweenspecific emotions?Since the late 1800’s the question ofemotion-specific autonomic nervous systemactivity has been explored. This explorationstarted with James (1890) and Cannon (1927)who could only explore the issue from atheoretical basis.William James (1890)believed emotions were the result specificchanges in skeletal muscles and otherphysiological changes, the self-awareness ofwhich created the emotion. Since then, asecond wave of interest sparked research inthe 1950’s which provided some evidence foremotion-specific ANS activity (e.g. Ax 1953).However, the research methodologies wereflawed, providing questionable results.Athird wave of research was initiated in the1980’s led by Paul Ekman.Ekman hascontinued to examine the relationship189Polygraph, 2009, 38(3)

An Exploration of Emotion and CognitionAlthough these studies suggest thatthere is evidence for emotion-specific ANSarousal, other studies have failed to showconsistent results. It may be that the primaryobservable physiological responses are notsufficientlymeasuredwithcurrentinstrumentation, such as used during PDD.to a threatening event. One that can activateresponses because of a memory of a similarlyappraised encounter can act faster andperhaps respond more effectively.Another possible example that offers apotential for a reinstatement of an emotion isthe negative social connotations associatedwith lying. It is important to recognize thatlying is both a goal-directed and commonbehavior, intended to reduce anxiety or threatassociated with the truth about informationfor which a lie is told. This may occur in partbecause people are social creatures who oftentend to seek approval and acceptance of theirfellow humans, though they sometimes lie toachieve these goals.Most children aresocialized from an early age to equate honestywith honor and goodness, that dishonesty isfrowned upon, and that lying brings aboutpunishment. We recognize that sometimeslying can also bring about reward when thedeceptive behavior is not confronted. Thechoice to lie rests on the conclusion that lyingwill produce less internal anxiety or externalconsequences than would tell the truth.While lying is almost universally disapprovedof, children are also socialized to understandthe subtle boundaries surrounding s. In most societies lying informal settings such as in discussions with aperson in a position of authority is stronglydiscouraged and in some cases such lying ispunished severely when it is discovered. Forexample, lying to a federal law enforcementofficer during the course of an investigation isa felony in itself. It would seem there is apotential for anxiety to be associated withopenly breaching such societal rules. There isalso the potential for positive and conflictedemotions as the person hopes and seeks toobtain a desired result through telling a lie.From a PDD standpoint, this mayseem like gloomy news if we were to beclaiming to be able to pinpoint "fear" fromamong the many other potential emotionalstatesanexamineemayexperience.Fortunately we do not have to subscribe to a"fear-driven" theory of PDD testing.Wesuggest we do not know and could not knowwhat specific emotion or emotions may becontributing to ANS changes we measureduring PDD in any particular individual.Instead we are content to admit that whatevercontribution emotion makes to changes in ourmeasurements, it is sufficient to allow us toeffectively differentiate truthfulness fromdeception.4) What does all this mean for PDD?Imagine you are at the dentist having acavity filled and the anesthesia is ineffective atmasking the pain of the drill. As the dentistdrills into your molar you experience a sharppain coinciding with the sound of the drill.You hope your reaction to the pain will causethe dentist to stop and remedy the situation.But what about the next time you hear thesound of the dentist drill? It is possible thatthe sound of the drill can produce not only acognitive response in the form of a memory,but may also result in an associativeemotional reaction. This is an example ofreinstatement of memory, or classicalconditioning, of an earlier-formed evaluationwhich generates emotions "as if" an appraisalis occurring. The appraisal and the emotionshould not be confused for being the samething.When classical conditioning hasoccurred the appraisal work has already beendone and the memory of the appraisal hasbeen stored for this stimulus, allowing theemotion to more quickly and more reflexivelyoccur. One need not stretch his imagination toappreciate the evolutionary benefits of suchability. Long term survival would seem morelikely in an organism that does not have toperformacompleteappraisalbeforegenerating an emotion and action in responsePolygraph, 2009, 38(3)In our view the act of lying about theissue itself, for some people, may cause thetest questions to function as a form ofconditioned stimuli, reproducing a learned orassociated internal anxiety state that is theresult of a lifetime of conditioning experience.This experience may have resulted fromaccepting and rehearsing a system ofsocialized values that emphasize goodnessand honesty. The possibility of getting caughtin a lie and/or the punishment associatedwith being caught can generate a negative190

Khan, Nelson, Handleremotional state. Thus even in a laboratorysetting (where there is little jeopardy) the actof lying may create sufficient emotionality orconflicted response to produce measurablephysiological reactions. Similarly, conditionedresponses stemming from the behavioral actitself, independent of the act of lying about theevent, may also play an additive role in thedevelopment of observable and measurablepolygraph reactions, along with relatedneurobiological activity and mental effort.also free of the complex demands on attentionand cognitive systems, including any need tomanage presentation or appearance whilemaintaining a separation of the truth from thedevelopment and presentation of a plausiblealternative. The truthful examinee may devoteattention and effort to assess the likelihoodthat the test will result in an error, and thepotential consequences associated with anerror.However, our position is that theemotional and cognitive demands which therelevant test question stimuli place on thetruthful person are less than those required ofsomeone who is involved in and chooses to lieabout an event under investigation.Theeffectiveness of PDD stimuli would seem to becontingent upon whether there is reference toboth an event in question and the examinee'sinvolvement in that event.For example,someone being investigated for a bank robberymight be asked, "Did you rob that bank?"This manner of questioning would moredirectly associate the examinee with the act ofconcern than would an indirect approachinvolving question about lying, in person or inwriting, regarding the event in question (e.g.,Were you truthful in your written statementabout not robbing the bank?). We know fromconditioning studies that the closer a stimulusis to the conditioned target stimulus, thelarger the reaction (Kehoe & Macrae, 2002).Cognitiveprocessessurroundingknowledge and memory of having engaged inan act can increase the salience of a testquestion about that act. Pretest discussionand review of the test question is thought toincrease the salience of the test question for aperson involved in the event, by stimulatingthoughts, memory, and emotional experiencepertaining to the event. Persons uninvolved inthe event described by the test question havenoassociatedmemories,thoughtsoremotional experience regarding the details ofthe incident. The memory tasks involved inlying can require additional mental effort orincreased cognitive load, while attempting tosuppress a memory or thought and divertattention to another matter when presentedwith the test stimulus question. Liars need tocreate their lie, assess that lie with regard toplausibility or believability, keep the liestraight during possibly numerous retellingsand not confuse the lie with the truth. Liarsalso need to keep the lie separate from thetruth and they need to monitor themselvesmore carefully in order to ensure they appeartruthful and avoid giving away the falsehoods.In addition to the need to marshal sufficientmental ability to manage the contentcomplexity and tell the lie in a convincing andcoherent manner, liars must also try toconceal any emotional reaction which mayoccur in response to the ei

Polygraph. 3 Mark Handler is a former law enforcement examiner, the Research and Information Chairperson for the American Association of Police Polygraphists, and a regular contributor to the journal Polygraph. Authors' Note: The authors are grateful to Barry Cushman, Chuck Slupski, Leonard Salcedo, Elmer Criswell, Toby .