Transcription

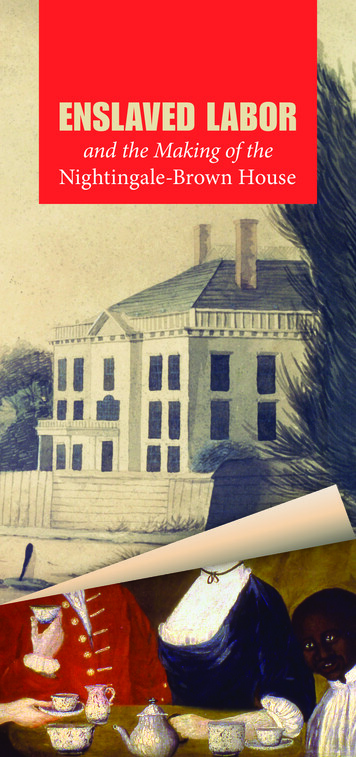

ENSLAVED LABORand the Making of theNightingale-Brown House

Rhode Islanders played a centralrole in the American slave tradeduring the 1700s. A total of about onethousand slave-trading voyages sailed from thissmall state to the coast of Africa, then to the WestIndies, in what has been called the triangulartrade. The slave trade was a key component inthe growth of wealth in Rhode Island, but eventhe “middling sort”—artisans, shopkeepers, andskilled laborers and tradesmen—invested in sharesof a slaving voyage or purchased an enslaved laborer to assist in their shops and stores.In 1784, the firm of Clark& Nightingale, along withProvidence slave traderCyprian Sterry, invested inthe slaving voyage of the brigPrudence, which led to thedeaths of nine captives. Thispage from the 1795–96 log ofthe slave ship Mary, ownedby Sterry, describes an uprising onboard in which fourcaptives were killed.Courtesy of the Booth FamilyCenter for Special Collections,Georgetown University.Between 1700 and 1750, the enslaved population inRhode Island grew faster than the white population. In 1755, African-descended people constituted11.5% of the Rhode Island population and about 9%of the population of Providence.Beginning in the early 1700s, slavery came under attack in Rhode Island, led by the Society ofFriends (Quakers). In 1783, Quaker Moses Brownintroduced a gradual emancipation bill making allchildren born to enslaved persons free at 18 yearsof age if female and 21 years of age if male. The billalso removed barriers to individual manumission.Gradually the number of people enslaved in RhodeIsland diminished. The first Federal census in1790—two years before Joseph Nightingale commissioned the construction of this house—recorded nearly a thousand people enslaved in RhodeIsland. By 1820, there were 48. In 1842, a new stateconstitution made slavery illegal in Rhode Island.

Slavery andJOSEPH NIGHTINGALEThe Nightingale family was part of a closelyconnected community of families that formed trading partnerships, invested in joint ventures, andfrequently intermarried. Supporting this network ofmerchant families and businesses was a small armyof enslaved laborers. The historical record yields alimited amount of information about enslaved people in the household of Joseph Nightingale, but weknow that he owned enslaved people who resided inhis home on Water Street from 1770 through 1791,and we can be reasonably certain that some of themmoved with Joseph’s family into his new mansionon Benefit Street in 1792.John Potter (1716–1787), a wealthy Rhode Islandplanter, commissioned this portrait of hisfamily. Included is a young boy, almost certainlya slave. The artist painted him lower than thePotters, on the same level as their elaboratetea service. This suggests that they includedhim in the painting as a possession and a statussymbol, rather than as a member of the family.Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society, Estate ofE. L. Winters, 53.3.The 1782 Rhode Island Census provides some detailsabout enslaved people in the Nightingale household.At that time, Joseph’s household included two “mulatto” males under age 16 and one between 22 and 50;two black males between 16 and 22; three black malesbetween 22 and 50; and one black male “upwards of50,” for a total of nine black people. The First FederalCensus of 1790 and the Providence Census of 1791 recorded four free and five enslaved black people working in his household—again, a total of nine.

In August of 1783, Moses Brown heard reports that his friendsJohn Clark and Joseph Nightingale were intending to dispatcha ship to Africa. The result was this letter, recounting Brown’sexperience with the disastrous voyage of the Sally and begginghis friends not to repeat his mistake. Had the Sally neversailed, he wrote, “I should have been preserved from an Evil,which has given me the most uneasiness, and has left thegreatest impression and stain upon my own mind of any, if notall my other conduct in life.” Nightingale and Clark electednot to heed the advice. Their ship, the Prudence, sailed forAfrica a short time later.Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society. RHi X17 3911In 1789, Joseph Nightingaleand John Innes Clark financeda slaving voyage, which ledto the sale of seventy-eightcaptives in Havana the following year. A View of theEntrance of the Harbour of theHavana, 1768.Courtesy of the John Carter BrownLibrary at Brown University.

Clark and Nightingale, the business Joseph foundedwith John Innes Clark, owned at least two enslavedpeople, and a third apparently worked for them asa store clerk. Clark and Nightingale also profitedfrom two slaving voyages. In October 1784, thepartners and three other Providence merchantssent the brig Prudence to the African coast. ThePrudence boarded 88 African captives and arrivedin Georgia nine and a half months later. The 79captives who survived the grueling Middle Passagedebarked and began a life of enslavement. Fiveyears later, Clark and Nightingale underwrote asecond slaving voyage, this time as sole owners. TheProvidence boarded 87 African captives and debarked 78 survivors in Havana in July 1790. Aboutone year later, Joseph Nightingale began construction of his new home, financed partially from theproceeds of these voyages.This 1758 painting byJohn Greenwood, calledSea Captains Carousing inSurinam, depicts a group ofRhode Island ship captainsin a tavern amidst Africanslaves. Of the ten men inthe painting who have beenidentified, six were futuretrustees of the College ofRhode Island, today BrownUniversity, and two becamegovernor of Rhode Island.John Greenwood, American,1727–1792; Sea Captains Carousing inSurinam, c.1752–58; oil on bed ticking;37 3/4 x 75 inches; Saint Louis ArtMuseum, Museum Purchase 256:1948.

The so-called Clark and Nightingale Block is perhaps misnamed since the oldest section, to the right in this 1958photograph of the rear of the building, was likely built a fewyears after Joseph Nightingale’s death. Located a short distance from Clark’s and Nightingale’s homes on Benefit Street,it probably served as a warehouse and retail store.Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.Slavery and theNIGHTINGALE MANSIONIn 1792, Joseph Nightingale moved his family intothe elegant mansion built for him on Benefit Street.There is no reason to believe that he would havereduced his household staff upon moving into amore spacious house. It is likely that the same fiveenslaved and four free black people who residedwith the family on Water Street moved with themto Benefit Street.Just five years later, John Innes Clark reported thesudden and “melancholy death of my late worthyFriend & Partner, who expired in an apoplectic fiton Friday morning between 9 & 10 O’clock withoutthe least complaint or even a groan.” There is norecord of who took ownership of his slaves, exceptfor the two owned by the firm, Nimble and Joseph,who were manumitted by Clark in January of 1798.Clark and Nightingale advertised a variety of goods andsupplies available at their shopon Water Street in Providenceincluding “articles of WestIndia Produce”, likely derivedfrom slave labor. The firmowned or employed at leastthree enslaved persons.Alice Pelham Banniter painted this watercolor of “Mr.Nightingale’s House at Providence, Rhode Island” around1802 while she was a student of Archibald Robertson at hisColombian Academy of Painting in New York.Courtesy of the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities andCultural Heritage, Brown University.

Bristol Nightingale was free and living with sixother people according to the 1790 census, possiblyoperating a rooming house. He married MarthaMonday in 1808 and Martha Carter in 1810.Quam Nightingale purchased his freedom fromClark & Nightingale in July 1790, and was livingwith one other person, perhaps his wife.While enslaved, Polly Nightingale was treatedin the Providence smallpox hospital in 1776. Shemarried Samuel Greene in 1793.While enslaved, Cudge Nightingale worked forClark & Nightingale as a clerk in their retail shop.He was a free man by 1803, identified as a “labourer”in Scituate, Massachusetts. He maintained contactsin Providence, where he purchased household supplies of sugar, coffee, tea, and liquor.The first Federal Censusin 1790 identified peopleby race, gender, and statusas free or enslaved. QuamNightingale is identifiedas one of two “other freepersons” in his household,indicating his statusas a former slave.Courtesy ofthe US Census Bureau.THE ENSLAVED PEOPLEWhat happened to the enslaved and formerlyenslaved people who identified themselves with thesurname “Nightingale”? Several appear in censuses,legal documents, and other sources, but the recordis sparse. Their stories are an important part ofthe history of this house, and their names shouldbe remembered.Joshua Nightingale achieved his freedom sometime before 1806, and he made a living as a marinerand laborer.Randall Nightingale was free by 1811, and heworked as a mariner.Joseph Nightingale, identified as a “mulatto,” wasfreed by the Providence Town Council in 1798 afterthe death of Joseph Nightingale. He married a woman named Sarah, but the marriage did not last. In1799, Joseph published a newspaper notice disavowing Sarah’s debts. In 1805, he married Olive Mancy.Nimble Nightingale was emancipated in 1798along with Joseph. His 1793 marriage to CandiceGreene was recorded by the First CongregationalSociety, of which he was a member. He worked forthe Nightingale family unloading ships from 1807to 1809. The 1810 Federal Census includes Nimblein a household of three, possibly with Candice anda child. In 1826, Nimble’s death was reported in twonewspapers, which identified him as a “professor ofthe Christian Religion.”

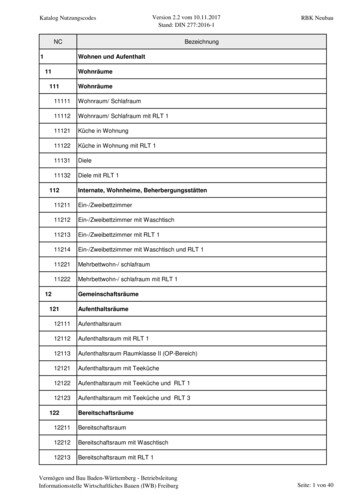

Joseph Nightingale’sBUSINESS OF SLAVERY— 1747Joseph Nightingale is born in Pomfret, Connecticut— 1751–52 The Nightingale family moves to Providence— 1769Joseph Nightingale co-founds the firm of Clark andNightingale with John Innes Clark— 1774The Rhode Island census lists two “Indians” andfour “Blacks” in Joseph’s Nightingale’s household— 1782Joseph Nightingale is recorded as having nine peopleof color working in his household on Water StreetREMEMBER— 1783Rhode Island passes a gradual emancipation law— 1784Clark and Nightingale invest in the slaving voyageof the brig Prudence, resulting in the enslavementof 79 Africans (nine others died on board).— 1789Clark and Nightingale finance the slaving voyageof the Providence, resulting in the enslavement of78 Africans (nine others died on board)— 1790Joseph Nightingale is recorded as having fourfree and five enslaved black people working in hishousehold on Water StreetWhen Nicholas Brown, Jr., purchased theNightingale mansion on Benefit Street in 1814, hetoo brought with him a family history steeped inthe business of slavery. Most of the commercialinterests that made the Browns the most powerfulmerchant family in Providence had been connectedin one way or another with the slave trade. But by1814, the slave trade had become illegal, and slaveryitself was quickly disappearing. There would beno enslaved people living in Nicholas Brown’s newhome on Benefit Street.Quam Nightingale purchases his freedom fromClark and Nightingale— 1791The Providence census identifies five enslavedpeople living in Joseph Nightingale’s household onWater Street— 1791–92 Joseph Nightingale’s mansion on Benefit Street is built— 1797Death of Joseph Nightingale— 1798Nimble Nightingale and Joseph Nightingale,“servants of John Innes Clark and the late JosephNightingale” are freed by Clark— 1800Joseph Nightingale’s son, John Clark Nightingale,finances the slaving voyage of the brig Ida,resulting in the deaths on board of 69% of the 162captive Africans— 1814Nicholas Brown, Jr., purchases the formerNightingale mansion— 1842The new Rhode Isand Constitution makes slaveryillegal in the stateThe parlor contains paneling original to the house,and floorboards may have been trod upon by theNightingale household. There is little else left fromthe Nightingale family or from the enslaved andfree black people who labored here. The house itselfstands as a monument to their labors, as well as to theinstitution, slavery, that helped finance its construction. It is the responsibility of the current inhabitantsof the Nightingale-Brown House to remember thenames and stories of these “black Nightingales.”The parlor of the Nightingale-Brown House retains wallpaneling from Joseph Nightingale’s period of ownership.Courtesy of the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities andCultural Heritage, Brown University. Photo by Jesse Banks.

The information in this pamphlet is derived from “BlackLabor in the Making of theNightingale-Brown House”(2018), by Joanne Pope Melish.The report was commissionedby the John Nicholas BrownCenter for Public Humanitiesand Cultural Heritage.Additional research and writing was undertaken by SophieDon, Zelin (William) Pei, YiruZhang, and Ron Potvin.The John Nicholas BrownCenter would like to acknowledge the Center for the Studyof Slavery & Justice (CSSJ). TheCSSJ’s exhibition, Hidden inPlain Sight: American Slaveryand the University and itsaccompanying brochure servedas an important template forthis project.Arielle Julia Brown and ChEWare of the CSSJ’s BlackSpatial Relics project providedinspiration for this project.

Providence slave trader Cyprian Sterry, invested in the slaving voyage of the brig Prudence, . Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. In August of 1783, Moses Brown heard reports that his friends John Clark and Joseph Nightingale were intending to dispatch a ship to Africa. The result was this letter, recounting Brown's