Transcription

DOCUMENT RESUMEED 361 652AUTHORTITLEINSTITUTIONCS 011 387Koskinen, Patricia S.; And OthersCaptioned Video and Vocabulary Learning: AnInnovative Practice in Literacy Instruction.National Reading Research Center, Athens, GA.;National Reading Research Center, College Park,MD.SPONS AGENCYREPORT NOPUB DATENOTEPUB TYPEEDRS PRICEDESCRIPTORSIDENTIFIERSOffice of Educational Research and Improvement (ED),Washington, DC.NRRC-39320p.ReportsDescriptive (141)GuidesClassroom UseTeaching Guides (For Teacher) (052)Viewpoints(Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120)MF01/PC01 Plus Postage.Class Activities; Grade 4; Intermediate Grades;Reading Achievement; *Reading Comprehension; *ReadingImprovement; Reading Instruction; Video Equipment;*Vocabulary Development*Closed Captioned TelevisionABSTRACTThe addition of captions to television is atechnological breakthrough that can be used to enhance the vocabularyand comprehension skills of young readers. Taken together, severalstudies suggest that captioned television is a motivating mediumforbelow-average readers and bilingual students, and that simultaneousprocessing (audio/video/text) enhances learning. Of themany uses ofcaptioned video in the development of literacy.skills, vocabularylearning appears to be one of the most valuable. A fourth-gradeteacher, and other teachers at the same school, havecapitalized onthe power of video, using it as a way to get children excited aboutideas in the world, particularly about science and social studiesconcepts. Suggestions teachers have found useful when usingcaptionedvideo include: get to know the equipment; select a high-interestcaptioned video; preview the video; locate related texts;introducethe video; provide opportunities for rewatching the video;and createa video library. Captioned television captures students' attention,and its multisensory presentation of information decreasesthedifficulty of learning new words. The combination of thevideo actionwith spoken dialogue and printed words is a powerfultool in learningto read. (Contains 19 references.) **************************Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made**from the original *******************************

.0Patricia S. KoskinenRobert M. WilsonLinda B. Gambrel!Susan B. NeumanAMMIIIMMeoNRRCNational Reading Research CenterInstructional Resource No. 3Summer 1993U.S. DEPAWTMENT OF EDUCATIONOffice ot Educational Research and ImprovementEDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATIONCENTER (ERIC)XThis document has been reproduced asreceived born the perSOn or OrganIzalKmf2origrnatingMinor changes have been made to irnOnWereproduction QualityPoints of view Of opinions stated in this doc ument do not necessarily representOERI position Or POSiCyBESJ COPY MIAMI

NRRCNational Reading Research CenterCaptioned Video & Vocabulary LearningAn Innovative Practice in Literacy InstructionPatricia S. KoskinenRobert M. WilsonLinda B. GambrellUniversity of Maryland College ParkSusan B. NeumanTemple UniversityINSTRUCTIONAL RESOURCE NO. 3Summer 1993Cover photo courtesy of Children's Television WorkshopThe work reported herein was prepared with partial support from the National ReadingResearch Center of the University of Georgia and University of Maryland. It wassupported under the Educational Research and Development Centers Program(PR/AWARD NO. 117A20007) as administered by the Office of Educational Researchand Improvement, U.S. Department of Education. The findings and opinions expressedhere do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the National ReadingResearch Center, the Office of Educational Research and Improvement, or the U.S.Department of Education.3

NRRCNattonalReading ResearchCenterExecutive CommitteeNational Advisory BoardDonna E. Alvermann, Co-DirectorUniversity of GeorgiaJohn T. Guthrie, Co-DirectorUniversity of Maryland College ParkJames F. Baumann, Associate DirectorUniversity of Georgk2Patricia S. Koskinen, Associate DirectorUniversity of Maryland College ParkPhyllis W. AldrichSaratoga Warren Board of Cooperative EducationalServices, Saratoga Springs, New YorkArthur N. ApplebeeState University of New York, AlbanyRonald S. BrandtAssociation for Supervision and CurriculumDevelopmentMarsha T. De LainDelaware Department of Public InstructionCarl A. GrantUniversity of Wisconsin-MadisonWalter KintschUniversity of Colorado at BoulderRobert L. LinnUniversity of Colorado at BoulderLuis C. MollUniversity of ArizonaCarol M. SantaSchool District No. 5Kalispell, MontanaAnne P. SweetOffice of Educational ResParch and finprovement,U.S. Department of EducationLouise Cherry WilkinsonRutgers UniversityJo Beth AllenUniversity of GeorgiaJohn F. O'FlahavanUniversity of Maryland College ParkJames V. HoffmanUniversity of Texas at AustinCynthia R. HyndUniversity of GeorgiaRobert SerpellUniversity of Maryland Baltimore CountyPublications EditorsResearch Reports and PerspectivesDavid Reinking, Receiving EditorUniversity of GeorgiaLinda Baker, Tracking EditorUniversity of Maryland Baltimore CountyLinda C. De Groff, Tracking EditorUniversity of Georgiainstructional ResourcesLee Galda, University of GeorgiaResearch HighlightsTechnical Writer and Production EditorSusan L. YarboroughUniversity of GeorgiaWilliam G. HollidayUniversity of Maryland College ParkPolicy BriefsJames V. HoffmanUniversity of Texas at AustinVieeosShawn M. Glynn, University of GeorgiaNRRC StaffBarbara F. Howard, Office ManagerMelissa M. Erwin, Senior SecretaryUniversity of GeorgiaBarbara A. Neitzey, Administrative AssistantValerie Tyra, AccountantUniversity of Maryland College ParkNRRC - University of Georgia318 AderholdUniversity of GeorgiaAthens, Georgia 30602-7125(706) 542-3674Fax: (706) 542-3678INTERNET: toRRCOuga.cc.uga.eduNRRC - University of Maryland College Park2102 J. M. Patterson BuildingUniversity of MarylandCollege Part, Maryland 20742(301) 405-8035Fax: (301) 314-9625INTERNET: NRRCOumailumd.edu

About the National Reading Research CenterThe National Reading Research Center (NRRC)tion to conduct research on reading and readingtheir own philosophical and pedagogical orientations and trace their professional growth.Dissemination is an important feature of NRRCactivities. Information on NRRC research appearsinstruction. The NRRC is operated by a consortiumin several formats. Research Reports communicateof the University of Georgia and the University ofMaryland College Park in collaboration with researchers at several institutions nationwide.The NRRC's mission is to discover and docu-the results of original research or synthesize thefindings of several lines of inquiry. They are writtenprimarily for researchers studying various areas ofreading and reading instruction. The PerspectiveSeries presents a wide range of publications, fromis funded by the Office of Educational Researchand Improvement of the U.S. Department of Educa-ment those conditions in homes, schools, andcommunities that encourage children to becomeskilled, enthusiastic, lifelong readers. NRRC researchers are committed to advancing the develop-ment of instructional programs sensitive to thecognitive, sociocultural, and motivational factorsthat affect children's success in reading. NRRCresearchers from a variety of disciplines conductstudies with teachers and students from widelydiverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds incalls for research and commentary on research andpractice to first-person accounts of experiences inschools. instructional Resources include curriculummaterials, instructional guides, and materials forprofessional growth, designed primarily for teachers.For more information about the NRRC's research projects and other activities, or to have yourname added to the mailing list, please contact:prekindergarten through grade 12 classrooms.Research projects deal with the influence of familyand family-school interactions on the developmentof literacy; the interaction of sociocultural factorsand motivation to read; the impact of literaturebased reading programs on reading achievement;the effects of reading strategies instruction oncomprehension and critical thinking in literature,science, and history; the influence of innovativegroup 1.-larticipation structures on motivation andlearning; the potential of computer technology toenhance literacy; and the development of methodsand standards for alternative literacy assessments.The NRRC is further committed to the participation of teachers as full partners in its research. Abetter understanding of how teachers view thedevelopment of literacy, how they use knowledgefrom research, and how they approach change inthe classroom is crucial to improving instruction. Tofurther this understanding, the NRRC conductsschool-based research in which teachers exploreDonna E. Alvermann, Co-DirectorNational Reading Research Center318 Aderhold HallUniversity of GeorgiaAthens, GA 30602-7125(706) 542-3674John T. Guthrie, Co-DirectorNational Reading Research Center2102 J. M. Patterson BuildingUniversity of MarylandCollege Park, MD 20742(301) 405-8035

NRRC Editorial Review BoardPat:P.41a AdkinsUniversity of GeorgiaLynn* Diaz-RicoCynthia HyndCalifornia State University-SanBernardinoUniversity of GeorgiaRobert JimenezPeter AftlerbachUniversity of Maryland College ParkN. Jean DreherUniversity of OregonUniversity of Maryland College ParkKaren JohnsonJo Beth AlienUniversity of GeorgiaPamela DunstonPennsylvania State UniversityUniversity of GeorgiaPatty AndersUniversity of AdzonaJames KingJim FloodUniversity of South FloridaSan Diego State UniversityTom AndersonSandra KimbrellUniversity of Illinois at UrbanaChampaignDana FoxUniversity of ArizonaWest Hall Middle SchoolOakvrood, GeorgiaIrene BlumUnda Gambrel!Kate KirbyPine Springs Elementary SchoolFalls Church, VirginiaUniversity of Maryland BaltimoreCountyGwinnett County Public SchoolsLawrenceville, GeorgiaJohn BorkowskiValerie GarfieldSophie KowzunNotre Dame UniversityChattahoochee Elementary SchoolCumming, GeorgiaPrince George's County School DistrictLandover, MarylandShenie Gibney-ShermanRosary Lai ikAthens-Clarke County School DistrictAthens, GeorgiaVirginia Polytechnic InstituteCynthia BowenBaltimore County Public SchoolsTowson, MarylandMartha CarrUniversity of GeorgiaRachel GrantUniversity of Maryland College Pa,:rSuzanne Clew*Montgomery County Public SchoolsRockville, MarylandBarbara GuzzettiJoan ColeyJane HaughWestern Maryland CollegeCenter for Developing LearningPotentialsSilver Spring, MarylandArizona State UniversityMichael LawUniversity of GeorgiaSarah McCartheyUniversity of Texas at AustinLisa Mc FailsUniversity of GeorgiaMichelle CommeyrasUniversity of GeorgiaGeorgia Southern UniversityDonna MarleyBeth Ann HerrmannLinda CooperUniversity of South CarolinaShaker Heights City School DistrictShaker Heights, OhioKathleen HeubachLouisiana State UniversityBarbara MichaloveUniversityKaren CostelloMike McKennaa GeorgiaFowler Drive Elementary SchoolAthens, GeorgiaConnecticut Department of EducationHartford, ConnecticutSusan HillAkIntunde MorakinyoUniversity of Maryland College ParkUniversity of Maryland College ParkKarin DahlSally Hudson-RossLesley MorrowOhio State UniversityUniversity of GoorgiaRutgers University

Bruce MuwayUniversity of GeorgiaMary RooUniversity of DelawareSusan NeumanTemple UniversityRebecca SammonsUniversity of Maryland College ParkPriscilla WaynantAwanna NortonM. E. Lewis Sr. Elementary SchoolSpada, GeorgiaPaula SchwanenflugelRolling Terrace Elementary SchoolTakoma Park, MarylandPrince George's County School DistrictUpper Marlboro, MarylandUniversity of GeorgiaJan. WestRobert SerpiCaroline NoyesLouise WaynantUniversity of GeorgiaUniversity of GeorgiaUniversity of Maryland BaltimoreCountyJohn.O'FlahavanBetty ShockleyUniversity of Maryland College ParkFowler Drive Elementary SchoolAthens, GeorgiaAllen WigileldUniversity of GeorgiaSusan SonnenscheinDortha WilsonFort Valley State CollegeJoan PagnuccoUniversity of Maryland BaltimoreCountySteve WhiteUniversity of GeorgiaUniversity of Maryland College ParkPenny OldfatherUniversity of GeorgiaBarbara PalmerSteve StahlUniversity of GeorgiaUniversity of Maryland College ParkAnne SweetMike PickleUniversity of GeorgiaJessie PollackMaryland Depadment of EducationBaltimore, Mary landOffice of Educational Researchand ImprovementLig Ing TaoUniversity of GeorgiaRuby ThompsonSally PorterClark Atlanta UniversityBlair High SchoolSilver Spring, MarylandLouise TomlinsonUniversity of GeorgiaMichael PressleyUniversity of Maryland College ParkJohn ReadonceUniversity of Nevada-Las VegasSandy TumarklnStrawberry Knolls Elementary SchoolGaithersburg, MarylandTorn ReevesUniversity of GeorgiaShelia ValenciaLenore Ringlet.New York UniversityBruce Van &alrightUniversity of WashingtonUniversity of Maryland College Park7Shelley WongUniversity of Maryland College Park

About the AuthorsPatricia S. Koskinen is Associate Director forProfessional Relations at the National ReadingResearch Center and a member of the GraduateFaculty at the University of Maryland. Herresearch focus is instructional strategies thatinfluence vocabulary learning and text comprehension, including retellings, repeated reading,and captioned television. She may be contactedat the National Reading Research Center, 2102J.M. Patterson Building, University of Maryland,College Park, MD 20742.Robert M. Wilson is Professor Emeritus at theUniversity of Maryland and, until recently, wasDirector of the University of Maryland ReadingClinic. His research focuses on comprehensionstrategy instruction and the use of signing andcaptioned television to enhance vocabularyknowledge. He may be contacted at 14506Perrywood Drive, Burtonsville, MD 20866.Linda B. Gambrell is a professor in the Depart-mcrit of Curriculum and Instruction at theUniversity of Maryland and a principal investiga-tor at the National Reading Research Center.Her research interests include motivation toread, comprehension strategy instruction, andearly literacy development. She may be contact-ed at the National Reading Research Center,2102 J.M. Patterson Building, University ofMaryland, College Park, MD 20742.Susan B. Neuman is an associate professor inthe Curriculum and Instruction and Technologyin Education Department at Temple University,where she is Coordinator of the Reading andLanguage Arts Graduate Program. Her researchcovers media and literacy, leisure reading, andplay as a context for literacy development. Shemay be contacted at Temple University, 437Ritter Hall, Philadelphia, PA 19122.

CaptionedDwayne and Annette carefully pulled thetelevision cart out of the closet andRicardo picked up the copies of the termitestory. These below-average readers in Mrs.VideoHowe's fourth grade class had been eagerly anticipating reading time becausetheir reading group was going to see thescience video with ugly baby termites intheir giant mound. The day before thesestudents had watched a captioned videoon African termites. The termite moundthey saw didn't look like the ant hill theyknew. It was 13:gger than a zebra and&VocabularyLearningAn Innovative Practicein Literacy Instructionalmost as tall as an elephant.After the previous day's video reading,Annette found a picture of a termitemound in Insects Do the Strangest ThingsPatricia S. KoskinenRobert M. WilsonLinda B. Gambrell(Hornblow & Hornblow, 1968) and didn'tthink it looked so big."Ricardo wasexcited when he discovered that his bookon bees had some of the same words heUniversity of Maryland College Parkhad seen on the captioned video.Susan B. NeumanHediscovered that bees live in a "colony" andthat they also have "workers" and aTemple University"queen." The pictures he found of littlehoneybee grubs didn't seem as awful asthe termite babies in the video. DianeNational Reading Research CenterUniversities of Georgia and MarylandInstructional Resource No. 3Summer 1993took the African termite story home toread to her brother, who loves bugs, andChris decided he was going to search forreal termites. He thought he might findsome at home because his mother had saidthe house was going to fall down if theydidn't get rid of the termites!The children in this fourth grade class-room have been learning to read andwrite in a literacy program that includes19

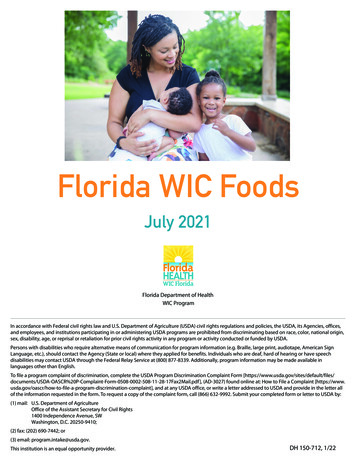

2Patricia Koskinen, Robert Wilson, Linda Gambrell & Susan NeumanFigure 1.Captioned Science Programthe use of captioned television as one ofmany reading materials. Captioned television is used as a supplement to the basicreading instructional program. While allchildren in this classroom had opportunities to view content-related televisionprograms with captions, the children whoare experiencing reading difficulties receive supplemental reading instructionwhich uses the captions on the video asreading material. Reading the captionsprovides these students with opportunitiesto engage in guided reading activities inthe highly motivating and i-einforcingcontext of television viewing.The addition of captions to U.S. com-mercial and public television programsprovides many opportunities for screenreading. Captions, which are similar tosubtitles on foreign films, can be seen ontelevision sets that have special electronicTele Caption decoders. A decoder, which iseasily attached to a television set, can bepurchased for approximately U.S. 160.Some schools have purchased decoders andteachers are now using high-interestcaptioned programming to develop literacyIn the near future, however, captions will be available at no additional costskills.to viewers of regular television due torecent legislation passed by Congress. TheTelevision Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990requires that all new television sets sold inthe United States after June 1993 haveNRRC National Reading Research Center

Captioned Video & Vocabulary Learningbuilt-in circuitry to decode and displayclosed-captioned programming.Captions were originally developed fordeaf and hearing-impaired viewers, buteducators of students with normal hearinghave found that captions can turn telfrvi-sion into a moving storybook. Captionsput words in a motivating environmentwhere the audio and video contexts helpviewers understand printed words theymight not know how to read.Because3that viewing television with captions washighly motivating.Most importantly, several studiesindicate that captions enhance the readingvocabulary and comprehension ofschool-age below-average readers (Adler,1985; Koskinen, et al., 1986; Koskinen,Wilson, Gambrell, & Jensema, 1987). Andanother study conducted with bilingualstudents found that those who viewedcaptioned videos performed significantlythere are now over 450 hours of captionedtelevision programming broadcast weeklyon the major networks and cable stations,educators are becoming increasingly awareof the many screen-reading opportunities.better on word identification, word meaning, and content learning assessments thanstudents who viewed the same videoswithout captions (Neuman & Koskinen,1992).Although much of the original re-Taken together, these studies suggestsearch on captioned television was conducted with deaf or hard-of-hearing indi-that captioned television is a motivatingviduals, during the last ten years a numbercomprehension skills of below-averageof research studies have focused on thepositive benefits of using captioned tele-readers and bilingual students.vision with students who have normalhearing. These studies have explored theeffects of captioned television on motivation, reading vocabulary, and readingcomprehension with below-average readers and bilingual students. Several studiessuggest that students with reading difficulties can and do read captions on television (Adler, 1985; Koskinen, Wilson,Gambrell, & Jensema, 1986). In a laterstudy conducted by Koskinen, Wilson,Gambrel!, and Jensema (1991),who receivedtwice-weekly captioned television instrucbelow-averagereaderstion over a two-month period reportedmedium for improving the vocabulary andThesestudies also support the theoretical notionthat simultaneous processing (audio/video/text) enhances learning.CLASSROOM USE OFCAPTIONED TELEVISIONBecause captioned video instruction involves the use of relatively new technology, research has also explored teachers'skill in developing and implementingwell-structured vocabulary and comprehen-sion lessons with captioned video materials. In a study conducted with 45 d supplemental reading lessonsinstructional Resource No. 3, Summer 19931

4Patricia Koskinen, Robert Wilson, Linda Gambrell & Susan Neumanusing captioned programs such as situationsemantically enriched context where visualcomedies, cartoons, and science videos(Koskinen, et al., 1991). Not only wasimages and sound lend meaning to theprinted words that appear on the screenthere high teacher and student satisfaction(Neuman & Koskinen, 1992).with these lessons, but objective evaluations by trained observers indicated thehigh quality of teacher-designed lessonsand an equally high level of student motivation and on-task behavior. All seventeachers involved in this study reportedthat captioned TV was well suited to thedevelopment of vocabulary skills. Theseteachers also suggested a variety of otherskills for which captioned video is wellsuited, such as prediction, character analysis, and sequencing. In addition, teachers'ratings of students' on-task behavior andinterest were exceptionally high.At the conclusion of the study, allparticipating teachers indicated that theywould use captioned television in theirclassrooms on the average of once or twicea week.Students participating in thestudy reported that they enjoyed watchingcaptioned TV programs and that watchingcaptioned TV helped them learn newwords.CAPTIONED TELEVISION ANDVOCABULARY LEARNINGResearchers have documented thatstudents learn new words through reading(Jenkins, Stein, & Wysocki, 1984; Nagy,Anderson, & Herman, 1987), estimatingthat they acquire 3,000 words per yearthrough wide reading (Nagy, Herman, &Anderson, 1985). As McKeown and hercolleagues have pointed out, word learning is related to the frequency of exposureto print (McKeown, Beck, Omanson, &Pop le, 1985). While many high-achievingstudents read extensively, low-achievingstudents often read infrequently, and thushave less exposure to print. We know,however, that many students spend agreat deal of time watching television.(Beentjes & Van Der V.,1988). If theywatch captioned television, they will berepeatedly exposed to words in contextand the opportunity for vocabulary learning will be enhanced. Stahl and Fairbanks(1986) also have noted the importance ofcontext in vocabulary instruction. In theirreview of 52 studies, they concluded thatdiscussed the need for learning words fromeffective vocabulary instruction involvescontextual as well as definitional instruction. Captioned television allows viewersto focus attention on both definitional andcontextual information; it enhances wordmeaning by providing a semantically richvisual setting that presents printed wordsin context with pictorial images (Neumancontext, and captioned video provides a& Koskinen, 1992).Of the many uses of captioned video in thedevelopment of literacy skills, vocabularylearning appears to be one of the mostvaluable. Nagy and Herman (1987) haveNRRC National Reading Research Center12

Captioned Video & Vocabulary LearningCaptioned television provides a presen-tation of information that includes opportunities to view the video action, hear thespoken word, and see the printed text.This multi-sensory presentation is appealing to students. Not only does it decreasethe difficulty of learning new words, but itisa medium with which students feelconfident (Koskinen, et al., 1991).Salomon (1984) noted that students perceive themselves as highly effective atprocessing information from television. Amajor problem for below-average readershas been attending to the reading task.The world of print has often been threatening for these students and many havefound that the best way to deal with thisthreat is to avoid reading. The motivatingqualities of captioned television in theinstructional setting can help studentsovercome this avoidance. They want towatch captioned television and are inter-ested in reading associated printed text(Koskinen, Wilson, &Koskinen, et aL, 1991).Jenseme,1985;Because of the enriched contextualsettingfor vocabulary learningandstudents' positive response to captionedvideo, teachers have become creative indeveloping vocabulary activities that usecaptioned video. These activities have thesame features of any well developed vocabulary lesson, including multiple oppor-tunities to interact with targeted wordswithin a meaningful context. The following example shows how one teacher used5captioned video to focus on vocabularydevelopment.HOW MRS. HOWE'S CLASS USESCAPTIONED TELEVISIONMrs. Howe's class had been studyinginsects,so she decided to use atwo-minute 3-2-1 Contact video toshow them an African termite colony.After telling the students that theywere going to watch a program abouthow new termite colonies are built,she put the phrase Alate termitecolonies on the chalk board. Shepointed to appropriate words in thephrase as she explained that theywere going to learn about the insideand outside of Alec termite colonies.She went on to activate prior knowl-edge by having a short discussionabout what students knew related tothe colony building of bees, ants, andtermites. After this discussion, Mrs.Howe gave a two-sentence introduction to the video and asked the students to watch the program carefullyand to read the captions so they coulddescribe the inside and outside of thetermite colony.After viewing the video and following up on the initial purpose ofdescribing the colony, Mrs. Howeintroduced the word mound, one offive key vocabulary words related tothe topic that were visually portrayedin the video. The students wereshown the word mound written on aword card and asked to look for it inInstructional Resource No. 3, Summer 199313

6Patricia Koskinen, Robert Wilson, Linda Gambrell & Susan Neumanthe captions while they watched thevideo a second time. When theyfound the word, they raised theirhands as a signal to pause the videoso the word couldbe discussed.When the students described theword mound, it was in elaborateterms, noting its height, color, texture, and purpose.Mrs. Howe pro-ceeded to introduce the individualwords build, chamber, colonies, andtunnels in a similar fashion. The students enjoyed talking about thewords while looking at their videoimages.After the screen reading, the students focused on the key words inprinted text. They were guided tofind these key words in a typed handout that contained sentences from thecaptioned video. As a conclusion tothe lesson, the students were encouraged to focus on the broader contextfrom which the words originally came.They were asked .what parts of theprogram they liked best and weregiven an opportunity to describe afavorite part. Mrs. Howe then previewed a few books from the librarycorner that contained informationN hook to books."The children whoviewed the African terrhite video wereeager to talk about what they had seenand to share their knowledge with others.The 254 minute science video providedthem with enough information so thatwhen they explored texts on termites, ants,and bees, they found familiar words andconcepts. Students were motivated to lookat magazines and books about otherinsects and discovered, for example, thatant colonies also had an intricate system of"tunnels" and "chambers" with "workers,""soldiers," and a "queen."The valuable activity of rereadingmaterial for different purposes is often adifficult task for below-average readers.Students who watched the termite video,however, were enthusiastic about reread-ing the captions as they rewatched thevideo. These students used the wordsfrom the captioned video in a variety ofways.Some students organized theirinformation about termites on a semanticmap, while others reviewed the video sothey could be the announcers and read thecaptions aloud with the sound turned off.about termites and other insects thatAs students wrote news articles on termites, bees, and ants for the classroomlive in colonies.newspaper, they rewatched the video andcompared it to information they found inMrs. Howe and other teachers at thesame school have capitalized on the powerof video, using it as a way to get childrenexcited about ideas in the world, particularly about science and social studies concepts. They have also used these videos asinsect books.In addition to reading the captions onthe television screen, some students alsohad the opportunity to read captions onpaper. Teachers have used caption scriptsas regular texts to develop reading skillsNRRC National Reading Research Center14

Captioned Video & Vocabulary Learningand promote interest in independentreading.The technology for taking cap-tions from television and printing themout on a personal computer has just re-7also learned words by simply viewingcaptioned video without the benefit ofInteacher-directed vocabulary instruction(Adler, 1985; Koskinen, et al., 1986;Neuman & Koskinen, 1992). These resultsthe near future, teachers will have easyaccess to printed reading material thathave led educators to suggest that, inaddition to using captioned video atcentl) become commercially available.comes directly from their students' favoritetelevision programs.There are a number of concerns relat-ed to the use of captioned video as asource of reading materials forschool, having captions available at homefor regular television viewing would provide opportunities for repeated exposureto print, thereby assisting vocabularydevelopment.Even though there arebelow-average readers that need to berecognized.First, the match betweenwhat one hears (the audio) and the printsubstantial differences betwee

Temple University. INSTRUCTIONAL RESOURCE NO. 3 . University of Washington. Bruce Van &alright University of Maryland College Park. 7. . University of Georgia. Allen Wigileld University of Maryland College Park. Dortha Wilson Fort Valley State College. Shelley Wong. University of Maryland College Park. About the Authors. Patricia S .