Transcription

ArticlesComparison of the efficacy and safety of new oralanticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrialfibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trialsChristian T Ruff, Robert P Giugliano, Eugene Braunwald, Elaine B Hoffman, Naveen Deenadayalu, Michael D Ezekowitz, A John Camm,Jeffrey I Weitz, Basil S Lewis, Alexander Parkhomenko, Takeshi Yamashita, Elliott M AntmanSummaryBackground Four new oral anticoagulants compare favourably with warfarin for stroke prevention in patientswith atrial fibrillation; however, the balance between efficacy and safety in subgroups needs better definition. Weaimed to assess the relative benefit of new oral anticoagulants in key subgroups, and the effects on importantsecondary outcomes.Methods We searched Medline from Jan 1, 2009, to Nov 19, 2013, limiting searches to phase 3, randomised trialsof patients with atrial fibrillation who were randomised to receive new oral anticoagulants or warfarin, and trialsin which both efficacy and safety outcomes were reported. We did a prespecified meta-analysis of all71 683 participants included in the RE-LY, ROCKET AF, ARISTOTLE, and ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trials. The mainoutcomes were stroke and systemic embolic events, ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, all-cause mortality,myocardial infarction, major bleeding, intracranial haemorrhage, and gastrointestinal bleeding. We calculatedrelative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs for each outcome. We did subgroup analyses to assess whether differences inpatient and trial characteristics affected outcomes. We used a random-effects model to compare pooled outcomesand tested for heterogeneity.Findings 42 411 participants received a new oral anticoagulant and 29 272 participants received warfarin. New oralanticoagulants significantly reduced stroke or systemic embolic events by 19% compared with warfarin (RR 0·81,95% CI 0·73–0·91; p 0·0001), mainly driven by a reduction in haemorrhagic stroke (0·49, 0·38–0·64; p 0·0001).New oral anticoagulants also significantly reduced all-cause mortality (0·90, 0·85–0·95; p 0·0003) and intracranialhaemorrhage (0·48, 0·39–0·59; p 0·0001), but increased gastrointestinal bleeding (1·25, 1·01–1·55; p 0·04). Wenoted no heterogeneity for stroke or systemic embolic events in important subgroups, but there was a greater relativereduction in major bleeding with new oral anticoagulants when the centre-based time in therapeutic range was lessthan 66% than when it was 66% or more (0·69, 0·59–0·81 vs 0·93, 0·76–1·13; p for interaction 0·022). Low-dose neworal anticoagulant regimens showed similar overall reductions in stroke or systemic embolic events to warfarin (1·03,0·84–1·27; p 0·74), and a more favourable bleeding profile (0·65, 0·43–1·00; p 0·05), but significantly moreischaemic strokes (1·28, 1·02–1·60; p 0·045).Interpretation This meta-analysis is the first to include data for all four new oral anticoagulants studied in the pivotalphase 3 clinical trials for stroke prevention or systemic embolic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. New oralanticoagulants had a favourable risk–benefit profile, with significant reductions in stroke, intracranial haemorrhage,and mortality, and with similar major bleeding as for warfarin, but increased gastrointestinal bleeding. The relativeefficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants was consistent across a wide range of patients. Our findings offerclinicians a more comprehensive picture of the new oral anticoagulants as a therapeutic option to reduce the risk ofstroke in this patient population.Lancet 2014; 383: 955–62Published OnlineDecember 4, 0See Comment page 931Brigham and Women’s Hospitaland Harvard Medical School,Boston, MA, USA (C T Ruff MD,R P Giugliano MD,Prof E Braunwald MD,E B Hoffman PhD,N Deenadayalu MPH,Prof E M Antman MD); JeffersonMedical College, Philadelphia,PA, and CardiovascularResearch Foundation,New York, NY, USA(Prof M D Ezekowitz MBChB);St George’s University, London,UK (Prof A J Camm MD);McMaster University and theThrombosis andAtherosclerosis ResearchInstitute, Hamilton, ON,Canada (Prof J I Wetiz MD);Lady Davis Carmel MedicalCenter, Haifa, Israel(Prof B S Lewis MD); Institute ofCardiology, Kiev, Ukraine(Prof A Parkhomenko MD); andThe Cardiovascular Institute,Tokyo, Japan(Prof T Yamashita MD)Correspondence to:Dr Christian T Ruff, Thrombolysisin Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)Study Group, 350 LongwoodAvenue, 1st Floor Offices,Boston, MA 02115, USAcruff@partners.orgFunding None.IntroductionAtrial fibrillation, the most common sustained cardiacarrhythmia, predisposes patients to an increased risk ofembolic stroke and has a higher mortality than sinusrhythm.1,2 Until 2009, warfarin and other vitamin Kantagonists were the only class of oral anticoagulantsavailable. Although these drugs are highly effective inprevention of thromboembolism, their use is limited by anarrow therapeutic index that necessitates frequentmonitoring and dose adjustments resulting in substantialwww.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014risk and inconvenience. This limitation has translatedinto poor patient adherence and probably contributes tothe systematic underuse of vitamin K antagonists forstroke prevention.3,4Several new oral anticoagulants have been developedthat dose-dependently inhibit thrombin or activatedfactor X (factor Xa) and offer potential advantages overvitamin K antagonists, such as rapid onset and offset ofaction, absence of an effect of dietary vitamin K intakeon their activity, and fewer drug interactions. The955

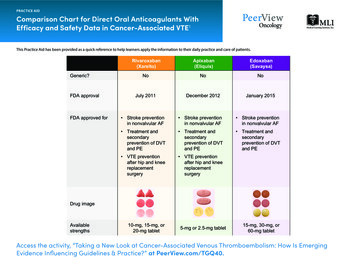

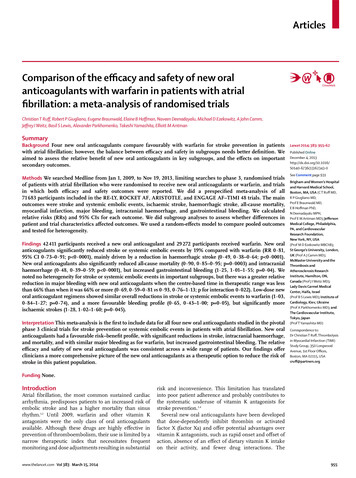

Articlespredictable anticoagulant effects of the new anticoagulants enable the administration of fixed doseswithout the need for routine coagulation monitoring,thereby simplifying treatment. Individually, new oralanticoagulants are at least as safe and effective aswarfarin for prevention of stroke and systemic embolismin patients with atrial fibrillation.5–8 Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban have been approved by regulatoryauthorities, whereas edoxaban has completed late-stageclinical assessment.Although previously published meta-analyses havebeen done of trials comparing new oral anticoagulantswith warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation,9–13 thisanalysis is the first to include data from the EffectiveAnticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation inAtrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48)8,14 with edoxaban,the largest of the four trials. All four trials were poweredto address their primary endpoints; however, the balancebetween efficacy and safety in important clinical subgroups needs better definition. We aimed to enhanceAge (years)RE-LY5ROCKET-AF6Dabigatran Dabigatran Warfarin(n 6022)110 mg150 mg(n 6076) (n 6015)Rivaroxaban(n 7131)precision in assessment of the relative benefit of new oralanticoagulants in key subgroups, and the effects ofthese drugs on important secondary outcomes, to offerclinicians a more comprehensive picture of the new oralanticoagulants as a therapeutic option to reduce the riskof stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation.MethodsStudy selectionWe undertook a prespecified analysis of the four phase 3,randomised trials comparing the efficacy and safety ofnew oral anticoagulants with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: RandomizedEvaluation of Long Term Anticoagulation Therapy(RE-LY; dabigatran),5 Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral DirectFactor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin KAntagonism for Prevention of Stroke and EmbolismTrial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF),6 Apixaban forReduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Eventsin Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE),7 and the ENGAGEAF–TIMI 48 study (edoxaban).8ARISTOTLE7Warfarin(n 7133)Apixaban(n 9120)ENGAGE AF-TIMI 488Warfarin(n 9081)Edoxaban60 mg(n 7035)Edoxaban30 mg(n 7034)CombinedWarfarin(n 7036)NOACWarfarin(n 42 411) (n 29 272)71·5 (8·8)71·4 (8·6)71·6 (8·6)73 (65–78)73 (65–78)70 (63–76) 70 (63–76)72 (64–68) 72 (64–78) 72 t or ysmal33%32%34%18%18%15%16%25%26%25%24%22% 75 yearsWomenAtrial fibrillation typeCHADS2*2·2 (1·2)2·1 (1·1)2·1 (1·1)3·5 (0·94)3·5 (0·95)2·1 (1·1)2·1 (1·1)2·8 (0·97)2·8 (0·97)2·8 (0·98)2·6 (1·0)2·6 (1·0)0–132%33%31%0034%34% 1% 1% 33%33%32%87%87%30%30%54%53%53%48%50%Previous stroke or TIA*20%20%20%55%55%19%18%28%29%28%29%30%Heart on79%79%79%90%91%87%88%94%94%94%88%88%Prior myocardial infarction17%17%16%17%18%15%14%11%12%12%15%15% 50 mL/min19%19%19%21%21%17%17%20%19%19%19%19%50–80 mL/min48%49%49%47%48%42%42%43%44%44%45%45% 80 mL/min32%32%32%32%31%41%41%38%38%37%36%36%Previous VKA use§50%50%49%62%63%57%57%59%59%59%57%57%Aspirin at �02·01·91·91·81·82·82·82·82·2Creatinine clearance‡Median follow-up (years)¶Individual median TTRNANA67 (54–78)NA58 (43–71)NA66 (52–77)NANA68 (57–77)NA2·265 (51–76)Data are mean (SD), median (IQR), or percent, unless otherwise indicated. NOAC new oral anticoagulant. CHADS2 stroke risk factor scoring system in which one point is given for history of congestive heartfailure, hypertension, age 75 years, and diabetes, and two points are given for history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack. TIA transient ischaemic attack. VKA vitamin K antagonist. TTR time in therapeuticrange. NA not available. *ROCKET-AF and ARISTOTLE included patients with systemic embolism. †ROCKET-AF included patients with left ventricular ejection fraction 35%; ARISTOTLE included those with leftventricular ejection fraction 40%. ‡RE-LY 50 mL/min, 50–79 mL/min, 80 mL/min; ARISTOTLE 50 mL/min, 50–80 mL/min, 80 mL/min. §RE-LY, ARISTOTLE, and ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 patients who usedVKAs for 61 days; ROCKET AF patients who used VKAs for 6 weeks at time of screening. ¶IQRs not available.Table: Baseline characteristics of the intention-to-treat populations of the included trials956www.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014

ArticlesStatistical analysisWe obtained information about the following outcomesfrom the main trial publications, supplemental appendices, and relevant subsequent analyses:5–8,15–23 strokeand systemic embolic events, ischaemic stroke,haemorrhagic stroke, all-cause mortality, myocardialinfarction, major bleeding, intracranial haemorrhage(including haemorrhagic stroke, epidural, subdural,and subarachnoid haemorrhage), and gastrointestinalbleeding. When possible, we did analyses with theintention-to-treat population for efficacy outcomes andwith the safety population for bleeding outcomes. InRE-LY5 and ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48,8 two doses ofdabigatran and edoxaban, respectively, were comparedwith warfarin. Rather than combining data with bothdoses into one meta-analysis, which would merge thebenefit and risk of different doses, potentially compromising interpretability, we undertook a metaanalysis with both higher doses (dabigatran 150 mgtwice daily for RE-LY and edoxaban 60 mg once daily forENGAGE AF–TIMI 48) combined with the single dosesstudied in ROCKET AF6 (rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily)and ARISTOTLE7 (5 mg twice daily). In a separateanalysis we undertook a meta-analysis of the two lowerdoses (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for RE-LY andedoxaban 30 mg once daily for ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48).We did two sensitivity analyses including a meta-analysis of only the factor Xa inhibitors, with removal of thethrombin inhibitor dabigatran, and an analysis combining all doses of all drugs (both high and low doses ofdabigatran and edoxaban with rivaroxaban and apixaban). We did not use any data from phase 2 doseranging studies because of their small sample size andshort follow-up, which precluded comparable ascertainment for all the outcomes analysed.We calculated relative risks (RRs) and corresponding95% CIs for each outcome and trial separately andchecked findings against published data for accuracy.When necessary, we calculated numbers of outcomeevents on the basis of event rates, sample size, andduration of follow-up. Outcomes were then pooled andcompared with a random-effects model.24 We assessed theappropriateness of pooling of data across studies with useof the Cochran Q statistic and I² test for heterogeneity.25We assessed comparative efficacy and safety for strokeor systemic embolic events and for major bleeding (theprimary efficacy and safety outcomes) in importantclinical subgroups: age ( 75 vs 75 years), sex, history ofprevious stroke or transient ischaemic attack, historyof diabetes, renal function (creatinine clearance 50 mL/min, 50–80 mL/min, 80 mL/min), CHADS2risk score (0–1, 2, 3–6), vitamin K antagonist status atstudy entry (naive or experienced), and centre-basedtime in therapeutic range (threshold of 66% vs 66%).The centre-based time in therapeutic range is the meantime in therapeutic range at each enrolling centreachieved in its patients randomised to warfarin. Therange is used as a surrogate of the quality of control ofinternational normalised ratio for all the patientsreceiving warfarin at that site. All four of the trialsreported the centre-based time in therapeutic rangeachieved in their respective warfarin groups by quartiles.We selected our threshold of centre-based time intherapeutic range because RE-LY, ROCKET AF, andARISTOTLE all had a quartile boundary near 66% andbecause the threshold differentiates the efficacy andsafety of oral anticoagulants from dual antiplatelettherapy.6,16,22 Because we had access to the clinicaldatabase in ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48, we could run thisanalysis at a threshold of 66%. We did all analyses withComprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2).Role of the funding sourceThere was no funding source for this study. Allauthors had full access to all the data in the study andhad final responsibility for the decision to submit forpublication.Results42 411 participants received a new oral anticoagulant and29 272 participants received warfarin. The table showsbaseline characteristics for each study. The average ageof patients was similar between trials as was theproportion of women recruited (table). However, theunderlying risk for stroke differed significantly acrossthe trials as shown by the proportion of patients withCHADS2 scores of 3–6 (table). Median follow-up rangedfrom 1·8 years to 2·8 years and the median time inNOAC (events) Warfarin (events)RR (95% CI)RE-LY5*134/6076199/60220·66 (0·53–0·82)p0·0001ROCKET AF6†269/7081306/70900·88 /90810·80 (0·67–0·95)ENGAGE AF–TIMI 488§296/7035337/70360·88 (0·75–1·02)0·10Combined (random)911/29 3121 107/29 2290·81 (0·73–0·91) 0·00010·51·0Favours NOAC2·0Favours warfarinFigure 1: Stroke or systemic embolic eventsData are n/N, unless otherwise indicated. Heterogeneity: I² 47%; p 0·13. NOAC new oral anticoagulant. RR risk ratio. *Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily. †Rivaroxaban20 mg once daily. ‡Apixaban 5 mg twice daily. §Edoxaban 60 mg once daily.www.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014957

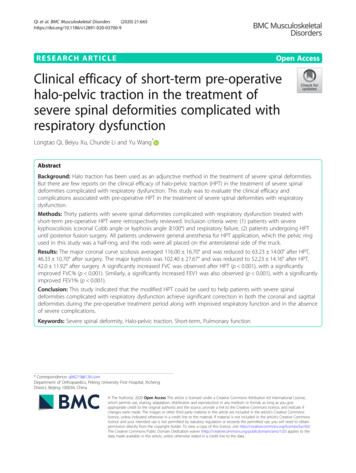

ArticlesSee Online for appendixtherapeutic range in patients in the warfarin groupsranged from 58% to 68% (table).Figure 1 shows the comparative efficacy of high-doseof new oral anticoagulants and warfarin. Allocation to anew oral anticoagulant significantly reduced the composite of stroke or systemic embolic events by 19%compared with warfarin (figure 1). The benefit wasmainly driven by a large reduction in haemorrhagicstroke (figure 2). New oral anticoagulants were alsoassociated with a significant reduction in all-causemortality (figure 2). The drugs were similar to warfarinin the prevention of ischaemic stroke and myocardialinfarction (figure 2).Randomisation to a high-dose new oral anticoagulantwas associated with a 14% non-significant reduction inmajor bleeding (figure 3). In line with the reduction inhaemorrhagic stroke, a substantial reduction in intracranial haemorrhage was observed, which includedhaemorrhagic stroke, and subdural, epidural, and subarachnoid bleeding (figure 2). New oral anticoagulantswere, however, associated with increased gastrointestinalbleeding (figure 2).The benefit of new oral anticoagulants compared withwarfarin in reducing stroke or systemic embolic eventswas consistent across all subgroups examined (figure 4).The safety of new oral anticoagulants compared withPooled NOAC(events)warfarin was generally consistent for the reduction ofmajor bleeding across subgroups, with the exception ofa significant interaction for centre-based time in therapeutic range (figure 4). We noted a greater relativereduction in bleeding with new oral anticoagulants atcentres that achieved a centre-based time in therapeuticrange of less than 66% than at those achieving a time intherapeutic range of 66% or more (figure 4).The low-dose new oral anticoagulant regimens hadsimilar efficacy to warfarin for the composite of strokeor systemic embolic events (appendix). When differentiated by stroke type, the low-dose regimens were associated with an increase in ischaemic stroke comparedwith warfarin, which was balanced by a large decreasein haemorrhagic stroke (appendix). Similar to thehigher-dose regimens, the low doses showed a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (appendix). Significantly more myocardial infarctions were reported withthe low-dose regimens than with warfarin (appendix).The low-dose regimens were associated with a nonsignificant reduction in major bleeding, but with asignificant reduction in intracranial haemorrhage.Gastrointestinal bleeding was similar between low-dosenew oral anticoagulants and warfarin (appendix).A meta-analysis of only the factor Xa inhibitors, withremoval of dabigatran, showed similar results to thePooled warfarin(events)RR (95% CI)pEfficacyIschaemic stroke665/29 292724/29 2210·92 (0·83–1·02)0·10Haemorrhagic stroke130/29 292263/29 2210·49 (0·38–0·64) 0·0001413/29 292432/29 2210·97 (0·78–1·20)0·772022/29 2922245/29 2210·90 (0·85–0·95)0·0003Intracranial haemorrhage204/29 287425/29 2110·48 (0·39–0·59) 0·0001Gastrointestinal bleeding751/29 287591/29 2111·25 (1·01–1·55)0·043Myocardial infarctionAll-cause mortalitySafety0·20·51Favours NOAC2Favours warfarinFigure 2: Secondary efficacy and safety outcomesData are n/N, unless otherwise indicated. Heterogeneity: ischaemic stroke I² 32%, p 0·22; haemorrhagic stroke I² 34%, p 0·21; myocardial infarction I² 48%,p 0·13; all-cause mortality I² 0%, p 0·81; intracranial haemorrhage I² 32%, p 0·22; gastrointestinal bleeding I² 74%, p 0·009. NOAC new oral anticoagulant.RR risk ratio.NOAC (events)Warfarin (events)RR (95% CI)pRE-LY5*375/6076397/60220·94 (0·82–1·07)ROCKET AF6†395/7111386/71251·03 ·71 (0·61–0·81) 0·0001444/7012557/70120·80 (0·71–0·90)0·00021 541/29 2871 802/29 2110·86 (0·73–1·00)0·06ENGAGE AF–TIMI 488§Combined (random)0·51·0Favours NOAC0·342·0Favours warfarinFigure 3: Major bleedingData are n/N, unless otherwise indicated. Heterogeneity: I² 83%; p 0·001. NOAC new oral anticoagulant. RR risk ratio. *Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily.†Rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily. ‡Apixaban 5 mg twice daily. §Edoxaban 60 mg once daily.958www.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014

ArticlesAPooled NOAC(events)Age (years) 75496/18 073 75415/11 188SexFemale382/10 941Male531/18 371DiabetesNo622/20 216Yes287/9096Previous stroke or TIANo483/20 699Yes428/8663Creatinine clearance (mL/min) 50249/553950–80405/13 055 80256/10 626CHADS2 score0–169/50582247/95633–6596/14 690VKA statusNaive386/13 789Experienced522/15 514Centre-based TTR 66%509/16 219 66%313/12 642Pooled warfarin(events)RR (95% CI)pinteraction578/18 004532/11 0950·85 (0·73–0·99)0·78 (0·68–0·88)0·38478/10 839634/18 3900·78 (0·65–0·94)0·84 (0·75–0·94)0·52755/20 238356/89900·83 (0·74–0·93)0·80 (0·69–0·93)0·73615/20 637495/86350·78 (0·66–0·91)0·86 (0·76–0·98)0·30311/5503546/13 155255/10 5330·79 (0·65–0·96)0·75 (0·66–0·85)0·98 (0·79–1·22)0·1290/4942290/9757733/14 5280·75 (0·54–1·04)0·86 (0·70–1·05)0·80 (0·72–0·89)0·76513/13 834597/15 3950·75 (0·66–0·86)0·85 (0·70–1·03)0·31653/16 297392/12 9040·77 (0·65–0·92)0·82 (0·71–0·95)0·600·512BAge (years) 751 317/18 460 751 328/10 771SexFemale751/8682Male1 495/14 530DiabetesNo481/11 278Yes872/7691Previous stroke or TIANo1 070/20 638Yes495/8669Creatinine clearance (mL/min) 50514/437650–801 104/10 139 80625/8681CHADS2 score0–176/30902530/74033–61 640/12 716VKA statusNaive656/12 776Experienced909/16 446Centre-based TTR 66%484/10 972 66%668/10 9441 543/18 3961 346/10 6860·79 (0·67–0·94)0·93 (0·74–1·17)0·28920/86451 548/14 5440·75 (0·58–0·97)0·90 (0·72–1·12)0·29678/11 294937/75830·71 (0·54–0·93)0·90 (0·78–1·04)0·121 280/20 619553/86000·85 (0·72–1·01)0·89 (0·77–1·02)0·70620/43461 174/10 228672/85950·74 (0·52–1·05)0·91 (0·76–1·08)0·85 (0·66–1·10)0·57126/3078597/74981 745/12 6110·60 (0·45–0·80)0·88 (0·65–1·20)0·86 (0·71–1·04)0·09786/12 8201 040/16 2650·84 (0·76–0·93)0·87 (0·70–1·08)0·78702/11 021736/11 0490·69 (0·59–0·81)0·93 (0·76–1·13)0·0220·20·5Favours NOAC12Favours warfarinFigure 4: Stroke or systemic embolic events subgroups (A) and major bleeding subgroups (B)Data are n/N, unless otherwise indicated. No data available from RE-LY for the following major bleeding subgroups: sex, creatinine clearance, diabetes, andCHADS2 score. For ROCKET AF no major bleeding data available in the TTR and diabetes subgroup and major and non-major clinically relevant bleeding was used forsubgroups of age, sex, CHADS2 score, and creatinine clearance. NOAC new oral anticoagulant. RR risk ratio. TIA transient ischaemic attack. VKA vitamin Kantagonist. TTR time in therapeutic rangemain meta-analysis for both stroke or systemic embolicevents and major bleeding (appendix). An additionalanalysis was done combining all doses of all drugs in onemeta-analysis (including both high and low doses ofdabigatran and edoxaban with rivaroxaban and apixaban;www.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014appendix). Inclusion of low doses of dabigatran andedoxaban decreased the magnitude of the reduction inrisk of stroke or systemic embolic events with new oralanticoagulants and resulted in less bleeding thanwarfarin (appendix).959

ArticlesDiscussionOur results show that stroke and systemic embolic eventswere significantly reduced in patients receiving neworal anticoagulants. This benefit was mainly driven bysubstantial protection against haemorrhagic stroke,which was reduced by half. Conceptually, haemorrhagicstroke is a complication of anticoagulant treatment eventhough it is part of the overall efficacy assessment ofthese drugs. Importantly, overall intracranial haemorrhage (which includes haemorrhagic stroke) was reducedby roughly half, which represents a substantial benefit oftreatment with new oral anticoagulants. Intracranialhaemorrhage is a feared and often fatal complication ofanticoagulant treatment and about one in six firsthospital admissions for this disorder are related to suchtreatment.26 For the prevention of ischaemic stroke, thenew oral anticoagulants had similar efficacy to warfarin, which itself is very effective in this regard andreduces ischaemic stroke by two-thirds compared withplacebo.27 In general, the new oral anticoagulants had afavourable safety profile compared with warfarin; however, they were associated with an increase in gastrointestinal bleeding. They were also associated with asignificant reduction in all cause-mortality comparedwith warfarin.A separate analysis of the two low-dose new oralanticoagulant regimens showed that although they have asimilar efficacy to warfarin for protection against allstroke or systemic embolic events, they are not as effectivefor protection against ischaemic stroke in particular.However, they do have a safer profile than warfarin andpreserve the mortality benefit noted with the high-doseregimens. Consequently, low-dose regimens might be anappealing option for frail patients or for those who have ahigh risk for bleeding with full-dose anticoagulation.Panel: Research in contextSystematic reviewWe searched Medline from Jan 1, 2009 to Nov 19, 2013. Keywords were “atrial fibrillation”,“dabigatran”, “rivaroxaban”, “apixaban”, “edoxaban”, “oral factor Xa inhibitor”, “oralthrombin inhibitor”, and “warfarin”. We also did a search of ClinicalTrials.gov to identifyrelevant ongoing clinical studies. We restricted our analysis to phase 3, randomised trialsthat included patients with atrial fibrillation who were randomly assigned to receive neworal anticoagulants or warfarin, and trials in which both efficacy and safety outcomes werereported. We assessed the quality of identified studies to ensure minimisation of bias. Noformal scoring system was used to assess the quality of the evidence.InterpretationThis meta-analysis is the first to include results from all four new oral anticoagulants studiedin the pivotal phase 3 clinical trials for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.New oral anticoagulants showed a favourable risk–benefit profile with significant reductionsin stroke, intracranial haemorrhage, and mortality with similar major bleeding as warfarin,but increased gastrointestinal bleeding. The relative efficacy and safety of the anticoagulantswas consistent across a wide range of patients with atrial fibrillation. Our findings offerclinicians a more comprehensive picture of the new oral anticoagulants as a therapeuticoption to reduce the risk of stroke in this patient population.960A criticism of meta-analyses in this specialty is that thelarge phase 3 trials for stroke prevention in patients withatrial fibrillation were well powered to evaluate the maintreatment effect of their individual drug to reduce the riskof stroke or systemic embolic events compared withwarfarin. However, most trials are underpowered to detectdifferences in secondary outcomes and subgroups. Anexample is the analysis of all-cause mortality; onlyapixaban and low-dose edoxaban were associated withsignificant reductions in all cause-mortality, yet the pointestimates for the hazard ratios for all drugs (and doses)are very similar. The results of the meta-analysis supportthe premise that compared with warfarin, the new oralanticoagulants, as a class, reduce all-cause mortality byabout 10% in the populations enrolled in the clinical trials.Perhaps, more important than the provision of robustestimates of secondary outcomes is the ability of metaanalyses to enhance precision in assessment of therelative benefits of new oral anticoagulants in important,clinically relevant subgroups. Both risk of stroke andbleeding vary significantly across the range of patientswith atrial fibrillation. For example, vulnerable populations, such as elderly people (aged 75 years),28 patientswith a previous history of stroke,29,30 and those with renaldysfunction,31,32 have an increased risk of both ischaemicand bleeding events. Inclusion of these individuals intrials is variable and they are often underrepresented.Consequently, each trial alone can only offer partialreassurance that the overall balance of efficacy and safetyis preserved in these high-risk groups. For example,variations in the proportion of participants with aCHADS2 score of 3–6 were mainly attributable todifferential enrolment of patients with previous stroke ortransient ischaemic attack.33 This robust meta-analysis isthe first to show that the relative efficacy and safety ofnew oral anticoagulants is consistent across a broadrange of vulnerable patients (panel).We investigated whether the benefit of new oralanticoagulants was dependent on whether patients hadexperience with use of vitamin K antagonists beforeenrolment in the trial. Previous findings suggested thatpatients with little to no prior exposure to vitamin Kantagonists (ie, naive) had a higher risk of both ischaemicand bleeding events than experienced patients.34 A concernhas remained that new oral anticoagulants might havereduced benefit in experienced patients who have shownan ability to tolerate treatment with vitamin K antagonists.The results of our meta-analysis show that the benefit ofnew oral anticoagulants is consistent irrespective of apatient’s history with vitamin K antagonists.We also investigated whether the benefit of new oralanticoagulants was dependent on how well warfarin wasmanaged during the trial, as assessed by the centre-basedtime in therapeutic range.35,36 In the ACTIVE Wtrial,37 anticoagulant treatment had no significant benefitcompared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in centres with acentre-based time in therapeutic range that was less thanwww.thelancet.com Vol 383 March 15, 2014

Articlesthe median of 65%, whereas a reduction of more than twotimes was reported for vascular events in centres with atime in therapeutic range of more than 65%. The trialsincluded in this meta-analysis had varying success inmanagement of warfarin (median time in therapeuticrange 58–68%), and although they reported no heterogeneity in the results across their trial-specificquartiles,6,16,22 each trial was underpowered to detect adifference. In this meta-analysis, we examined a thresholdof 66% for centre-based time in therapeutic range, whichis similar to that used in the ACTIVE W analysis. Weshowed that the reduction in stroke or systemic embolismcompared with warfarin is not dependent on how wellwarfarin is managed, within the limitations of analysesbased on centre-based time in therapeutic range.However, an even more pronounced relative reduction inbleeding with new oral anticoagulants seems to take placein patients who have difficulty maintaining a therapeuticinternational normalised ratio.Because we did not have individual participant data forall the trials, our statistical approach was done at a studylevel. We pooled the data for the factor Xa inhibitors(rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) and the thrombininhibitor (dabigatran). Although these drugs inhibitdifferent coagulation factors, we believe that pooling ofthe results is justified for several reasons: the drugs are allspecific inhibitors of important f

New oral anticoagulants had a favourable risk-benefi t profi le, with signifi cant reductions in stroke, intracranial haemorrhage, and mortality, and with similar major bleeding as for warfarin, but increased gastrointestinal bleeding. The relative effi cacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants was consistent across a wide range of patients.