Transcription

M A SS I N CA R C ER A T I O NREVIEWToward an understanding of structural racism:Implications for criminal justiceJulian M. Rucker1* and Jennifer A. Richeson2*Racial inequality is a foundational feature of the criminal justice system in the United States. Herewe offer a psychological account for how Americans have come to tolerate a system that is so atodds with their professed egalitarian values. We argue that beliefs about the nature of racism—as beingsolely due to prejudiced individuals rather than structural factors that disadvantage marginalizedracial groups—work to uphold racial stratification in the criminal justice system. Although acknowledgingstructural racism facilitates the perception of and willingness to reduce racial inequality in criminaljustice outcomes, many Americans appear willfully ignorant of structural racism in society. We reflect onthe role of psychological science in shaping popular understandings of racism and discuss how tocontribute more meaningfully to its reduction.1Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, The Universityof North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA.Department of Psychology and Institution for Social andPolicy Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA.2*Corresponding author. Email: julian.rucker@unc.edu (J.M.R.);jennifer.richeson@yale.edu (J.A.R.)Rucker et al., Science 374, 286–290 (2021)due to a profound, often willful ignorance of therole of structural racism in contemporary society.The psychology of group-based hierarchyIt is imperative to ground this discussion insocial dominance theory (SDT) (3), the prevailing psychological theory of societal hierarchy.SDT begins with the observation that groupbased hierarchies are ubiquitous among humansocieties. It asserts that, typically, these hierarchies are created on the basis of age, sex, and atleast one other dimension that is more arbitraryyet extremely meaningful in a given cultural context (e.g., race, ethnicity, religion). Irrespective ofthe dimension, members of dominant groupsallocate a disproportionately large share of asociety’s valued resources (e.g., homes, jobs) toone another, at the expense of members of subordinated groups. In the case of race-based hierarchy in the US, for instance, members of thedominant racial group (e.g., white Americans)have repeatedly allocated positive societal goods(e.g., personal freedom, property rights, educational opportunities, access to health care) tothemselves and negative societal goods (e.g.,environmental toxins) to members of subordinated racial groups. This pattern of allocation,codified by law, reinforced by cultural normsand practices, and enforced by both officialpolice as well as extralegal, vigilante groups, constitutes structural racism.Once a hierarchy is established, social stratification is advanced, protected, and exacerbated by systems and processes that operateon multiple levels. At the individual level, forinstance, both members of dominant groupsand members of subordinated groups becomemotivated to justify, and thus maintain, thesystem. Dominant group members are motivated to maintain their higher social status,prestige, and preferential treatment. Membersof subordinated groups are also often motivatedto maintain the very hierarchical system thatdisadvantages them because of a greaterpsychological need to feel that the world is15 October 2021Justifying racial hierarchyAccording to SDT, at the psychological level,efforts to increase, maintain, or even decreaseintergroup hierarchy are influenced by a constellation of values, attitudes, ideologies, andattributions known as legitimizing myths (orbeliefs). Hierarchy-attenuating beliefs (e.g., “innocent until proven guilty”) can serve as a challenge against societal inequality. By contrast,hierarchy-enhancing beliefs (e.g., negative racialstereotypes) are critical to preserving perceptions of societal fairness, despite the presence ofgroup-based inequality. The endorsement andespousal of hierarchy-enhancing beliefs is notlimited to members of dominant societal groups(4). For instance, periods of surprisingly widespread support for punitive criminal justice efforts among Black politicians and communitymembers may be understood, at least in part, asa product of the adoption of hierarchy-enhancingbeliefs [e.g., pathologizing Black criminality (7)].Hence, hierarchy-enhancing beliefs can bluntefforts by members of racially subordinatedgroups to challenge the system despite its severeracially disparate outcomes. Notably, a legitimizing belief does not have to be even remotely trueto be effective in maintaining the hierarchy; whatmatters is the extent to which enough peoplebelieve it to be true such that it justifies hierarchyenhancing policies, practices, and outcomes.For most of US history, when consideringracial inequality in criminal justice, Americanelites (e.g., elected officials, education leaders,scientists) and institutions actively propagated1 of 5Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Stanford University on October 22, 2021The criminal justice system in the US hasbeen marred by the presence of profoundracial inequality from its inception. Be itrunaway slave patrols, which set the stagefor contemporary policing; laws thatsought to criminalize everyday activities whenperformed by formerly enslaved individualsafter Reconstruction; or the bevy of discriminatory policies that led to an explosion inincarceration, disproportionately affecting Blackand Latinx Americans (1), racial inequalityhas been produced and reproduced within thestructures of the US criminal legal system. Yet,by and large, Americans not only toleratethese inequalities but also often support policiesthat exacerbate them. The persistence and broadacceptance of stark levels of racial inequalityin the US criminal justice system are decidedlyinconsistent with the oft-noted increase inAmericans’ embrace of racially egalitarianvalues during the past several decades (2).The purpose of the present Review is to shedlight on this paradox through the lens ofpsychological science.Although many psychological factors likelycontribute to this gap between Americans’ostensible embrace of racially egalitarianvalues and their tolerance of a racially inequitable criminal justice system, the factorwe consider here is how Americans thinkabout the nature of racism itself. Do Americans think racism in contemporary societyis primarily an interpersonal phenomenonthat originates in prejudiced individuals or astructural phenomenon that originates inpolicies or laws that systematically disadvantagemembers of marginalized racial groups? Wecontend that Americans’ tolerance of racialinequality in criminal justice outcomes is partlypredictable and controllable [see also systemjustification theory (4)].Especially pertinent to this Review, SDT argues that criminal legal systems in most societiesare thought to serve a hierarchy-maintainingfunction (3). Consistent with this perspective,members of subordinated groups throughoutthe world [e.g., Black Americans of lower socioeconomic status in the US (1), African and Asianindividuals in the UK (5)] tend to be disproportionately targeted for surveillance and punishment. Moreover, SDT argues that some actors(e.g., prosecutors) embedded within the largersystem typically work to maintain, if notenhance, the hierarchy, whereas others (e.g.,prosecutors) typically work to attenuate it,eventually resulting in a hierarchy-preservinghomeostasis. Ultimately, most members of thebroader society come to behave in ways thatsupport the system—consider, for instance, thereadiness with which white Americans call thepolice in response to the unwelcome presenceof racial minorities (6). Similarly, individualsliving in disadvantaged neighborhoods, as aresult of concentrated poverty and unemployment, may begin to engage in higher levelsof criminal activity, ultimately exacerbating and seemingly justifying the increasedpolice presence.

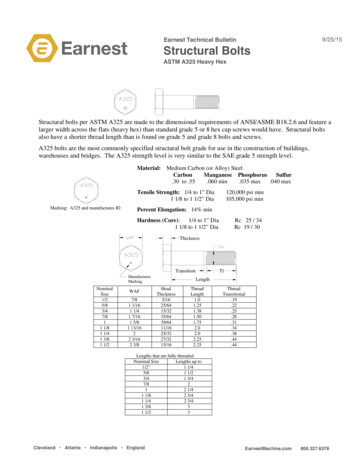

the hierarchy-enhancing myth that BlackAmericans are inherently more “criminal”than others, be it due to biology or culture,thus justifying the group’s unequal treatmentand outcomes (1, 8). Over the past severaldecades, however, belief in the fundamental,hierarchy-attenuating principle of racial equality began to take hold. For example, in thefirst major national surveys of racial attitudesin the US, conducted in the 1940s, 54% of thewhite Americans surveyed supported raciallysegregated public transportation and 54%thought that white Americans (versus BlackAmericans) should get preferential access tojobs. Only a few decades later (circa 1970s),support for equal access to public transportation and employment was so widespread amongwhite Americans that these items were droppedAfrom subsequent surveys (2). Indeed, this rise inegalitarian racial attitudes would seem to marka shift toward support for a less hierarchical,racially stratified society.Yet, during at least part of this same timeperiod, the numbers of incarcerated racialminority group members, especially BlackAmericans, began to rise exponentially (Fig. 1)(1). The inmate population of jails and prisonsin the US rose from 300,000 around 1970 toroughly 2 million less than three decades later.Between 1983 and 2000, the zenith of thisexplosion in mass incarceration, the numberof Black American prison inmates increased27-fold (1). In the context of this new, raciallyegalitarian zeitgeist, the existence of a justicesystem whose outcomes are systematicallyinfluenced by racism would seem intolerable.Home sellers can discriminate in salesFavor laws against intermarriageRight to segregate neighborhoodBlack students should go to separate schools80Percent 210Acquiring a structural understanding of racismThe role of informationWhitePrison admission rateImprisonment rate3001600Rate per 100,000 peopleRate per 100,000 001940196019802000YearFig. 1. Trends in self-reported racial egalitarianism and societal incarceration rates. (A) Declining self-reportsof racial prejudice among white Americans from 1972 to 2008. [Republished with permission of Princeton UniversityPress, from (55), permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.] (B) Rising prison admission andimprisonment rates for white and Black Americans from 1926 to 2010. [Republished with permission of TheNational Academies Press, from (56), permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.]Rucker et al., Science 374, 286–290 (2021)15 October 2021How do Americans learn about racism? Formany, especially members of the dominantracial group, it is primarily through formaleducational opportunities or the consumption of mass media, both of which have beenfound to limit, if not misrepresent, the verytypes of information that would foster an appreciation for structural racism (11–13). Forothers, especially members of racial minoritygroups, it is through formal education as well,but also partially through direct experience (14)coupled with the racial socialization effortsof family and community members (15–17).Although any of these informational pathwayscould lead to individuals’ acquiring information about racism in general and structuralracism in particular, there is reason to believethat these different routes to learning aboutracism contribute to the racial group differences in endorsement of an interpersonal orstructural view of racism. Indeed, Nelson andcolleagues (18) found that white participantswere less likely than Black participants to2 of 5Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Stanford University on October 22, 202170In the wake of this racially stratified criminaljustice system, alternative explanations forsystemic racial inequalities in carceral outcomes have emerged as a necessity.We argue that Americans tolerate starkracial inequality in carceral outcomes partlybecause they fail to appreciate structuralracism, focusing instead on the influence ofinterpersonal racism (e.g., focusing on “a fewbad apples” among police officers). Becauserecognizing the role of structural racism in thecriminal justice system would threaten its veryexistence, Americans are motivated to remainrelatively ignorant of the structural racismthat is endemic to criminal legal systems.Indeed, as recently as 2016, most Americansbelieved that racism in contemporary societyis primarily an interpersonal problem ratherthan a structural one (9). The outsized endorsement of an interpersonal rather than structuralview of racism is more prevalent among whiteAmericans than among racial minority Americans (10). Notably, we contend that, as animplication of widespread endorsement of thislegitimizing belief (e.g., the denial of structuralforms of racism), Americans tend to be lessresponsive to evidence of structural racismthan to evidence of interpersonal racism, bothwithin the criminal justice system and insociety more broadly. As a result, the raciallystratified institutions in society are preserved.Fig. 2 depicts a conceptual framework to shedlight on how hierarchical group rank (dominant versus subordinated) and motivationinfluence the acquisition of knowledge andunderstanding of structural racism that, inturn, shape the desire to maintain or dismantleracially inequitable systems and structures.

M A SS I N CA R C ER A T I O NRucker et al., Science 374, 286–290 (2021)The role of motivationDenying structural forms of racism, past andpresent, serves the broad motivation to protectthe group and self-image of white Americans[e.g., social identity threat (24)]. People arepsychologically motivated to maintain a global,positive self-view and will strive to mitigatethreats to their self-image (25, 26). Learningabout the racism that is foundational to thenation, especially as perpetrated by white Americans toward Indigenous peoples and racialminorities, can be experienced as a direct threatto the image of one’s racial or national identity(27, 28). Further, structural racism can alsopresent a meritocratic threat to white Americansinsofar as holding membership in a group thatmay be unfairly advantaged in society suggeststhat one’s successes may not be solely attributableto one’s own hard work, talent, and effort (29).These self-protective motives largely workin opposition to the educational and informational processes that facilitate the acquisitionof a structural understanding of societal racism.Consistent with this idea, Adams, Tormala,and O’Brien (30) found that affirming the selfconcepts of white participants before theywere exposed to potential incidents of racialdiscrimination toward Latinos led them tomore readily acknowledge that incidents werediscriminatory compared with white participants who had not been affirmed. Notably, areanalysis of these findings (31) revealed thatthis effect was stronger for incidents of systemicand/or structural discrimination than for moreinterpersonal incidents, which suggests thatthe denial of structural racial discrimination,in particular, is a motivated process.Although these motivations are more common among white Americans, as noted previously, members of racial minority groupscan also perceive information about societalracism as threatening (32). Further, it is possible for individuals—including those within thecriminal legal system—to be especially motivated to understand the systemic and structuralbases of racial inequality in society. Just as someactors work to maintain and enhance hierarchical systems, according to SDT, others work toreduce group-based hierarchies (33). Such individuals tend to value egalitarianism and havelow levels of social dominance orientation(SDO) (i.e., the preference for group-basedhierarchy) (3). Recent research suggest thatindividuals with lower levels of SDO are morelikely to notice evidence of inequality thantheir higher-SDO counterparts (34).Why does a structural understanding ofracism matter?We began this Review by noting the paradoxbetween the rise in Americans’ adoption ofracially egalitarian values and the coincidentrise in racial disparities in carceral outcomes(1, 35). One explanation, well-established in15 October 2021the social psychological literature, is the role ofwidespread implicit and/or automatic associations between young Black men and crime inshaping the views and behaviors of both thepolice and the public (36–38). We agree thatthese and other implicit racialized crime associations play an important role in the maintenance of systemic racial inequality in criminaljustice. Indeed, it is structural racism and theinequities it produces that support and sustainthese automatic associations between race andcrime. In other words, implicit bias is itself aconsequence of structural racism (39).Additionally we argue that Americans’ignorance of the role of structural racismin contemporary society contributes to ourwillingness to tolerate such stark levels ofracial inequity in criminal justice outcomes.Consider, for instance, New York City’s “stopand-frisk” program, which is ostensibly designed to get weapons off of the streets andallows the New York City Police Department(NYPD) to stop, question, and search individuals on the basis of “reasonable suspicion.”Between 2004 to 2013, the NYPD stopped4.8 million people, 80% of whom were Blackand Latino. Of those who were stopped duringthis period, both Black and Latino individualswere more likely to be frisked and less likely tobe found with a weapon than white individuals(40). In other words, the program producedracially disparate criminal justice outcomes.We contend that it may only be through theacknowledgment of structural racism thatthese disparities can be accurately perceivedand meaningfully addressed.Consistent with this position, we found thatindividuals who tend to have a more structural (versus interpersonal) understanding ofracism also tend to believe that racial minorities are disadvantaged in the criminal justicesystem relative to white Americans (41). Further, the tendency to endorse the idea that structural rather than interpersonal racism is a moreimportant problem in contemporary societyaccounts for a substantial amount of the gapbetween white and Black Americans’ perceptions that the criminal justice system isunfair. In other words, to the extent that whiteAmericans understand structural racism, theyalso tend to perceive societal inequality in a waythat is similar to Black Americans’ views.Because structural racism is characterizedby policies, practices, and/or laws that have adisparate impact on members of particularracial or ethnic groups, evidence of raciallydisparate outcomes is the first indicator ofits operation. Hence, racial disparities in adomain are likely to be met with extra scrutinyby people with a structural (but not necessarilythose with an interpersonal) understanding ofracism. Recent work suggests that absent anappreciation of structural racism, white Americans are likely to interpret evidence of racial3 of 5Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Stanford University on October 22, 2021acknowledge systemic forms of racism, in partbecause they had less knowledge about racismin US history than their Black counterparts.Similarly, Bonam and colleagues (19) foundthat an educational intervention designedto increase such historical knowledge (i.e., abrief lesson on racial “redlining” in US housingpolicy) subsequently increased the extent towhich participants acknowledged structuralforms of racism in contemporary society.In other words, one reason why white Americans largely fail to recognize the role of structural racism in the criminal justice system—andin general—is the dearth of critical education,and the presence of miseducation, on the topic.This stands in contrast to the direct and vicarious experiences with racial discrimination incriminal justice that racial minority Americanshave (14), in addition to exposure to historicalaccounts of mistreatment from parents, grandparents, and other members of their broadercommunity (15). It is no wonder, then, that onecomponent of civil rights activism in the 1960s,and again today, aims to increase awareness ofracism in US society through education.Such efforts, however, have always been metwith institutional obstacles. For example, growing scrutiny has been placed on media outlets’overreliance on and underscrutinization ofpolice accounts of crime reporting, especiallyin cases that may involve racial discrimination(20). Uncritical acceptance of these officialpolice accounts, coupled with the exclusion(if not erasure) of perspectives of membersof marginalized racial groups, leads to biasedperceptions of these police incidents amongthe larger public. Consider, for instance, thedemonstrably false official account of themurder of George Floyd submitted to mediaby the Minneapolis police department (21).Had there not been video footage of the eventto contradict this misleading account, it isentirely likely that no one would have beenheld accountable, and the officer’s deadlybehavior would have been sanctioned.Similarly, substantial political resistance, suchas recent efforts to ban “critical race theory”from US school curricula (22), also representsa noteworthy obstacle to increasing a structural understanding of racism in criminaljustice and beyond. Such efforts clearly illustratethe role that societal elites and institutions playin shaping not only how Americans learn aboutracism but whether they learn about it at all.The lack of education on structural racism incriminal justice is neither accidental nor unintentional (23). In line with SDT, these effortslikely reflect a motivation among the dominantgroup to maintain their place atop the statushierarchy by further propagating the denial ofstructural racism, a powerful legitimizing myth.Hence, it is important to consider the role ofmotivation as a barrier to the acquisition of astructural understanding of racism.

Hierarchy-legitimizing beliefsKnowledge of historical racismDenial of structural racismRacial group membership(Dominant versussubordinated)Informational factorsMotivational factorsCritical educationSystem threatsSocializationIdentity-based threatsDirect/vicarious racismexperiencesEgalitarian motivesPerception of racial inequalityReparative policypreferencesCollectiveactionFig. 2. A framework of the antecedents and consequences of denial of structural racism. Dominant versus subordinated racial group membership predictsdifferential exposure to racism (e.g., direct or vicarious experience, socialization, critical education), which informs individuals’ overall level of knowledge abouthistorical and contemporary racism. Group status also shapes individuals’ motivations (e.g., self- and/or group esteem, system justification) to seek information aboutracism and acknowledge (or deny) the existence of structural racism, which in turn predicts willingness to perceive racial inequality and support for reparativepolicies or collective efforts designed to redress it.Rucker et al., Science 374, 286–290 (2021)nalized racial groups. This insight was centralto the theorizing of Paulo Freire, who arguedthat education designed to foster a critical analysis of societal inequity is essential for membersof subordinated groups to reclaim their full humanity and resist their oppression (44). Morerecent empirical work has demonstrated thebenefits of developing an understanding ofstructural racism among marginalized youth,finding it to be associated with positive individual outcomes [e.g., improved mentalhealth, greater educational achievement andengagement (45)] as well as increased civicengagement (16).In sum, the literature surveyed here suggeststhat an appreciation of the structural natureof racism predicts not only the extent to whichindividuals perceive, or perhaps acknowledge,racial stratification in the criminal justice systembut also their propensity to support reparativesocial policies. Moreover, this work underscoresthe fact that for members of the dominantgroup (i.e., white Americans), strong egalitarianmotives are insufficient to disrupt the normalpsychological processes that result in the justification of racially inequitable criminal justiceoutcomes. Instead, egalitarian values need to bepaired with an appreciation for structural racism.For members of marginalized racial groups, developing a structural analysis of racism mayserve as an important buffer against internalizing negative stereotypes about one’s group and,ultimately, engaging in behaviors that serve tojustify the dominant group’s position. Moreover,a structural understanding of racism may beespecially vital to engendering collective actionto change the system, for both members of advantaged and disadvantaged groups.Summary and self-reflectionIn this Review, we sought to illustrate keysocial-psychological factors that shape themaintenance and justification of a racially15 October 2021unjust criminal justice system, despite largescale support for racially egalitarian values.Psychological motives to substantiate theracial hierarchy and protect one’s self-imagework against opportunities to increase exposure to critical education on the structuralunderpinnings of contemporary racial inequality.In essence, ignorance and denial of structuralracism protect against an indictment of thelegitimacy of the criminal justice system. By contrast, acknowledgment of structural racismin society motivates efforts to reduce raciallydisparate outcomes. With this framework, itbecomes clear that merely holding egalitarianattitudes is insufficient to reform and dismantlesystems that reproduce racial inequality—astructural understanding of racism is integralto these objectives.This work also has implications for psychological science as a field. We, as psychologists,should examine our role in encouraging, if notpromulgating, an interpersonal understanding of racism at the expense of more structuralaccounts (11, 23). Explicit (or implicit) animustoward or even stereotypes and beliefs aboutmembers of marginalized racial groups aretroublesome and worthy of comprehensiveinquiry, but it is essential that they be properlysituated in a structural context (39, 46). Moreover, these attitudes and beliefs stem from ourculture and our cultural products, be they theholidays we celebrate, the memorials we erect,the social policies we adopt, or the histories weteach. In other words, our collective culturalsocialization shapes what we come to believe,consciously or unconsciously, about the racialinequalities we observe, or fail to observe, andour explanations for those inequities (47). Tothe extent that this socialization communicatesthat some groups are valued more than othersor are more capable or suitable for certain tasksthan are others, our implicit and explicit attitudes will reflect these contingencies (48–50).4 of 5Downloaded from https://www.science.org at Stanford University on October 22, 2021disparities in incarceration through the lens ofstereotypes about racial minority criminality(36–38, 42), thereby justifying the inequality.Consistent with this notion, in a longitudinalstudy conducted shortly after HurricaneKatrina, O’Brien and colleagues (43) foundthat white undergraduate students in NewOrleans who held a relatively interpersonalunderstanding of racism, compared with thosewho held a structural understanding, wereless likely to perceive racism as a cause of theracially disparate relief efforts and outcomes.However, white Americans with a relativelystructural (versus interpersonal) understanding of racism—especially individuals with strongegalitarian attitudes—should be less likely tosupport punitive criminal justice policies afterexposure to evidence of racial disparities in thecriminal justice system (41). In a recent study,we examined this possibility directly and foundthat increasing awareness of structural racism(as opposed to increasing awareness of implicitracial biases) through an educational intervention led white Americans to express greatersupport for policies designed to reduce racialinequality (10). Similarly, Adams and colleagues(11) found that a multiday tutorial that expandedknowledge of the structural basis of racialdiscrimination increased support for antiracistpolicy initiatives (e.g., reparations, race-consciousadmissions policies), compared with a similar tutorial that focused exclusively on interpersonal racial bias and with a no-treatmentcontrol. Together, this work suggests that astructural understanding of racism may becrucial to motivate efforts to address the starkand obstinate racial disparities in criminaljustice, as well as in other societal domains.In addition to the implications for membersof groups atop the racial status hierarchy(e.g., white Americans), research suggests thata structural understanding of racism may haveimportant implications for members of margi-

M A SS I N CA R C ER A T I O NRE FE RENCES AND N OT ES1. M. Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Ageof Colorblindness (New Press, 2010).2. L. D. Bobo, in Racial Trends and Their Consequences,N. J. Smelser, W. J. Wilson, F. Mitchell, Eds. (NationalAcademies Press, 2001), vol. 1, pp. 264–3013. J. Sidanius, F. Pratto, Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theoryof Social Hierarchy and Oppression (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1999).4. J. T. Jost, M. R. Banaji, B. A. Nosek, Polit. Psychol. 25,881–919 (2004).5. D. Lammy, “The Lammy review: An independent review intothe treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and minorityethnic individuals in the criminal justice system” (HMG, view.6. V. M. Weaver, “Why white people keep calling the cops on blackAmericans” (Vox, 2018).7. J. Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment inBlack America (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017).8. K. G. Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race

justice system, alternative explanations for systemic racial inequalities in carceral out-comes have emerged as a necessity. We argue that Americans tolerate stark racial inequality in carceral outcomes partly because they fail to appreciate structural racism, focusing instead on the influence of interpersonal racism (e.g., focusing on "afew