Transcription

EGMONT KEYA SEMINOLE STORY

EditorsBradley Mueller, Alyssa BogeProduction - Design TeamJuan Cancel, Bradley Mueller, Dave Scheidecker,Seminole Media ProductionsContributersJames Billie (Bird Clan), Joe Frank (Panther Clan),Justin Giles (Tiger/Big Cat Clan, Muscogee (Creek) Nation),Ted Isham (Wind Clan, Muscogee (Creek) Nation),Lenny Ray Jim (Panther Clan), Willie Johns (Wild Cat Clan),Manuel Tiger (Wind Clan), Aaron Tommie, Ted Underwood(Sweet Potato Clan, Seminole Nation), Billie Walker(Panther Clan), Rita Youngman (Bird Clan)Paul Backhouse, Alyssa Boge, Nicholas Butler, DomoniquedeBeaubien, Stan Garner, Maureen Mahoney, RachelMorgan, Bradley Mueller, Anne Mullins, Dave ScheideckerCover ImageBeverly Bidney, PhotographerTable of Contents ImageDave ScheideckerPublished ByThe Seminole Tribe of FloridaTribal Historic Preservation Office30290 Josie Billie Highway, PMB 1004Clewiston, Florida 33440Tel: 863-983-6549 Fax: 863-902-1117www.stofthpo.comOur thanks to the Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Council for their support and guidance.THE COVER AND CONTENT OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE FULLY PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT AND CANNOT BEREPRODUCED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION.

Contents2481012141618Carrying The TorchThe Sands of FloridaEgmont KeyA Timeline of Egmont KeyThe Seminole Removal Trail 1858Prison GroundsPolly ParkerThe Removed2022262832343840Egmont Key ExpressionsThe Story Beneath our FeetEgmont ArtifactsPreserving NatureIsland Under ThreatWhy Do You Save an Island?Seminole VoicesChoosing a Path

Carrying The TorchEgmont Key’s tranquil scenery masks itsdisturbing past We are the descendants of our ancestors’triumphs and the atrocities they endured For many of its visitors, Egmont Key is adestination that combines Florida history with During the nineteenth century, the United Statesbeautiful scenery. The island is located at the seized the homelands of many Native Americans.mouth of Tampa Bay, just off the coasts of St. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forcibly displacedPetersburg and Bradenton. It is home to the Native Americans from familiar environments toEgmont Key Lighthouse, the Egmont Key National foreign territories, actions that would alter theirWildlife Refuge, and the remnants of the Spanish lives for generations. Many systemic issues within-American War era Fort Dade. Its 400-acres worth tribal communities today are undoubtedly theof panoramic views provides visitors with an aftermath of this colonialism.idyllic tourist attraction.The Seminole Wars were a part of these largeBut for Seminoles, Egmont Key is a relic that scale efforts to remove Native Americans west.unearths a myriad of emotions that clearly shows Seminole elders have shared stories passed downour resilience as Native Americans. Today, human to them of the experiences their ancestors livedenvironmental damage has caused it to become through during those dreadful periods in Seminolea fraction of the size it once was.history. Egmont Key was used as an internmentcamp to hold imprisoned Seminoles before they2

were transported west. It became known as the As Egmont Key fades away, its historicalSeminole version of Alcatraz and was even called relevance must live on the dark place due to the horrors that took placeAs the minority of minorities, it is essential thaton the island.as Native Americans, our history is told from ourIn 1858, the steamer Grey Cloud left Egmont perspective. In a society that often divides usKey, transporting 160 Seminoles west. Polly based on our perceived differences and historicalParker (Emateloye) was on board, but managed omissions, telling our stories for ourselves ensuresto escape after they stopped in the Florida that people learn the truth of who we truly arepanhandle at St. Marks. Her legacy can be seen as Natives. People of all races can sympathizein her many descendants who are today members with the plight of Native Americans because thenarrative of inferiority and forced relocation isof the Seminole Tribe of Florida.evident in world history.As a Seminole, it was important to me to visitEgmont Key so that I could experience the place As Native People, we are vitalized by ourwhere many of my ancestors were unwillingly indigenous cultures. As Seminoles, our fortitudeheld. I became enraged and saddened when defines us. From the guidance of our ancestors,I learned of the terrible events that happened we know that we can overcome seeminglyon the island. One could only imagine the fear insurmountable odds. As descendants of Pollyand confusion my ancestors lived with as they Parker, Billy Bowlegs, and many of our otherawaited uncertain futures, a far cry from the Seminole ancestors, it is our duty to carry thetorch they left for us. Their sacrifices and foresightfreedom they were accustomed to.are the foundation of our Tribe’s longevity.We must continue to share the knowledge wehave learned with future generations in orderto preserve the legacy our ancestors left us. Bydoing this, we can protect our people and assureour ancestors that Egmont Key will never erodefrom our hearts and minds. Its lessons will beforever etched in our memories and serve as asymbol of hope and progression for the future ofour people.Contributed by Aaron Tommie.Aaron Tommie is a Tribal member and employeeof the Seminole Tribe of Florida.Photo and digital imagery by Dave Scheidecker.3

The Sands of FloridaMy father, King Phillip,told me I was made of the sands of Florida,and that when I was placed in the ground,the Seminoles would dance and sing around my grave.- Coacoochee (Wild Cat)4

Florida and the Seminole Tribe of Florida (STOF) define the very being of one another.Today, the Seminoles’ home in the low lying Everglades is critically threatened by climatechange. The offshore island of Egmont Key has become the front line for the Tribe in acommunity effort to remember a difficult past that is today threatened with being washedaway. Community engagement, archaeology, and climate change collide on Egmont, an islandthat is central to the past, present, and future of the Tribe.The Seminole Tribe of Florida is one of two federally recognized tribes in the modern stateof Florida. They are the proudly unconquered Seminoles. Descendants of fewer than 500Seminoles who held out against impossible odds in South Florida swamps, the Tribe now hasroughly 5000 members. Military historians record three wars between the Seminoles and theUnited States which they have collectively dubbed ‘the Seminole Wars’. The Seminoles donot see this distinction and consider the whole period to be one long war when their survivalwas at stake. It is estimated that thousands of Seminoles were shipped or forcibly walkedwest during this period of bitter conflict. The legacy of the hardships that Seminole peoplefaced continue to affect their identity in the modern world.The northern beach of Egmont Key.Photo by Dave Scheidecker.5

In Miccosukee, one language that Seminolepeople speak, there is a separate word for anisland in the ocean (Yanh-kaa-choko) that isdifferent from the word for their island homesin the heart of the Florida Everglades. EgmontKey is one of these oceanic islands, located inthe Gulf of Mexico at the entrance to Tampa Bay.The island first came to the attention ofthe Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal HistoricThis map was created by Juan Cancel, Quenton Cypress,and Lacee Cofer to show how a map drawn from the historicSeminole perspective, rather than that of European settlers,might appear. The map text is written in the Miccosukeelanguage, with some English translations.6Preservation Office (THPO) during a routinemeeting. The THPO works to preserve anddocument the STOF’s cultural heritage, bothon and off modern reservations. The meetingwas a standard government to governmentconsultation with the U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers (USACE). They explained that EgmontKey was in danger of washing away and Corpsstaff wanted the Tribe’s opinion on preservingthe island. Having a vague memory about a

Seminole presence on the island, the THPObegan to investigate further.During our research it became apparentthat during the late 1850’s (non-Seminolehistorians’ Third Seminole War) the U.S.Army was having difficulty holding Tribalmembers in Fort Myers, on the Floridamainland, while they awaited deportation.To prevent Seminoles from escaping backinto the tropical labyrinth of the Everglades,the army identified a simple and harsh solution.Seminoles were transported on boat from FortMyers to Egmont Key while they waited for thepaddle steamer the Grey Cloud to take them toNew Orleans and the west. While in captivity onthe island many Seminoles perished.The question for the Seminole Tribe of Floridabecame ‘Do we want to remember this history?’In seeking an answer the STOF THPO began, asit always does, by actively engaging the Tribalcommunities and government we serve in the storyof Egmont Key. We spoke with Tribal membersone-on-one, arranged educational trips to theisland, published articles in the Seminole Tribune,attended community meetings, and gave talks atTribal schools. Community members visiting theisland were greeted with a stark reminder of theTribes’ fight for survival in Florida.Tribal Judge and respected elder, Willie Johns,summarized how Seminoles reacted to thishistory from Egmont Key saying, ‘We neverwant to forget what happened here.’ Since thegovernment to government consultation withthe USACE, Tribal members of all ages havereengaged with the story. The overwhelmingsentiment was that if there was any possibility ofsaving the island it should be investigated. ThenChairman of the Tribe James E. Billie took thecall to action and, in a July 29th 2013 letter tothen U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Sally Jewell,wrote that: “The history of this island is a matterof cultural memory for our people and we wishit to be preserved if at all possible so that theyouth of our tribe can visit this place and learnhow far we have come together.” Contributed by Dr. Paul N. Backhouse and Alyssa Boge.Paul Backhouse is the Senior Director of the Heritage andEnvironment Resources Office of the Seminole Tribe of Florida.Alyssa Boge is the Education Coordinator forthe Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum.7

Egmont KeyThis song, written by Rita Youngman (Bird Clan),captures both the beauty of the island and itstragic history.8

Oh that lighthouse shines on that big white beautiful islandWhile the sailboats glide off into that big, blue oceanTourists they ride that ferry boat just for funBut it reminds me of those shipped into that Seminole prisonTiny white crosses on Egmont KeyLonely reminders of our own SeminoleCaptives they came some remain in a mass graveI hear them calling out of the dunes on Egmont KeyOh those turquoise skies look just like a Guy LaBreeWhile the dolphin play in the waters of old TocobatcheeThe hot, white sands reflect all of the day’s heatWhile I ponder the history that’s buried beneath my feetSilent voices are calling my nameCome and find us, don’t let them take us awayOur lost souls are restless out on the beachTill this day. on Egmont KeyThe Lighthouse Cemetery.Photo by Dave Scheidecker.9

The island is named Egmont Key in honorof John Percival, the Second Earl ofEgmont and first Lord of the Admiralty.Multiple city centers sit on Tampa Bayincluding Tocobaga, Uzita, and Mocoso,home to ancestors of the modern daySeminole people.2,000 BC900 AD1757Don Francisco Maria Celi, a Spanish explorer, createsthe first map of Tampa Bay. He names the island SanBlas y Barreda.Egmont Key forms in the mouthof Tampa Bay. Ancestors of theSeminole Tribe begin using it as afishing location.10A17611847Holatta Micco, also known as Billy Bowlegs,leads the Seminole as the threat of continuedpressure to leave Florida grows, and openconflict resumes.1855The first lighthouse is constructedat Egmont Key, but is destroyed bya hurricane. The second lighthouse(shown here in 1910) is finished 10years later.1857-1858The U.S. Army selects Egmont Keyas the location for a prison camp.Hundreds of Seminole, mostlywomen, children, and elders, areimprisoned on Egmont Key beforebeing taken to “Indian Territory.”TIMELINEOF

During Prohibition, bootleggers usethe abandoned Fort Dade buildingsas hideouts. Federal Marshals lightfires to burn them out, burning downmost of the Fort Dade structures.Fort Dade is completed. Supporting fiveartillery batteries, the military baseencompasses the entire island.During the American Civil War theisland is used first by Confederate,and later Union, forces.1861-18641898190919211928198920132016The State of Florida establishesEgmont Key State Park.Fort Dade is decommissionedfollowing the end of the FirstWorld War.As the Spanish-American War looms,the U.S. selects Egmont Key as thelocation for a new coastal defensemilitary base: Fort Dade.EGMONTSeminole elders retrace the removaljourney of Billy Bowlegs, returning toEgmont Key for the first time since 1858.KEYA wildfire sparked by a lightning strike burns acrossEgmont Key over three days. The fire clears a widearea of underbrush that allows an archaeologicalsurvey to take place.11

The first thing the Seminole saw when theyentered Indian Territory was Fort Gibson, anda vast wilderness as far as the eye could see.Gibson was the last stop for many tribes on theTrail of Tears, and it was here that Native Peoplewere forced onto federal reservations.The United States Government officially held to the claimthat the Seminole were not a distinct people, but insteada breakaway group from the Creek Nation. When theSeminole arrived in Indian Country they were placed intothe Creek Reservation, and not their own land. The Creekhad allied with the U.S. Government during the Creek CivilWar in 1813, yet now the Seminole were told to live on theland of their enemy, and under Creek rule. The Seminolecontinuously lobbied and fought for their own land, andin 1856 won their independence, and a 2 million acrereservation. Billy Bowlegs and his people arrived onto thisland, but the Seminole Reservation was short lived. Whenthe United States Civil War ended, the government strippedthe Seminole of their Reservation lands, even though BillyBowlegs had led his people in support of the Union. TheOklahoma Seminole history is one of struggle and tragedy,yet also one of triumph, as they survived all the challengesput before them.In Louisiana the Seminole were kept at the New OrleansBarracks before being sent north. In 1866 the barrackswere renamed “Jackson Barracks” in honor of AndrewJackson, the man who had led the American forces againstthe Seminole, and created the policy of Indian Removal.12

The Seminole RemovalTrail 1858Polly Parker led a half dozen othersin an escape when the Grey Cloudstopped for fuel at Saint Marks.They travelled across Florida onfoot to rejoin their families nearLake Okeechobee.Billy Bowlegs was one of theprimary Seminole leaders inthe 1850s. After the U.S. Armyincursion into Seminole territory,he retaliated, beginning the finalphase of the Seminole War.Egmont Key became a concentration campfor hundreds of Seminole elders, women,and children.Captured or surrendered Seminole wereoriginally held at Fort Myers, a SeminoleWar army fort. It was here where they wereput on the steamer Grey Cloud for removal.13

The place where the Seminole were held hasbeen referred to in many terms. The officialarmy records referred to it as “The IndianDepot at Egmont Key.” Newspapers at the timecalled it a stockade, a prison, or even simplya place to “await removal.” The Seminolehave referred to it as “The Dark Place,” “OurAlcatraz,” or simply as a concentration camp.Archaeologically there is no sign left of thebuilding where the Seminole were held.Records tell us that a wooden blockhouse wasbuilt to hold the captured Tribal members. PollyParker, who had been imprisoned on EgmontKey, recounted being held in a stockade underarmed guard. No records have yet been foundshowing where this was.14Behind the lighthouse, just south of the cemetery,is a natural clearing. This area is broad, naturallyflat, and would be easily accessible to the docklocations of the 1850s. The soldiers of Fort Dadeused the area as a parade ground, and the CoastGuard built a helipad there for use in the mid20th century.Historians and researchers believe this clearingis the most likely location of the stockade thatheld the Seminole prisoners. The soldiers whobuilt the prison would have wanted an area closeto the lighthouse and the nearby dock, yet farenough away to not interfere with the dutiesof the lighthouse keeper. The open flat groundand easy access would have made this a perfectlocation for the prison.

Prison GroundsPhoto and text contributed by Dave Scheidecker.Dave Scheidecker is an archaeologist and the ResearchCoordinator for the Tribal Historic Preservation Office.15

Polly ParkerPolly Parker (Emateloye) was captured on FisheatingCreek in 1856, marched over to Egmont Key, forcedonto a ship called Grey Cloud, shipped on up theGulf of Mexico to New Orleans where she would walkthe Trail of Tears out west. But the ship stopped torefuel at Fort St. Marks, directly south of Tallahasseeand, somehow, Polly escaped.She walked through the woods and swamps all the wayback to the Okeechobee area and began to create theSeminole Tribe as we know it today.Eventually her children and their descendants wouldplay monumental roles in our modern Tribe. In fact,Polly’s great-great-grandkids are very prominentmembers of the Seminole Tribe. I wonder: Whatwould have happened if Polly had never escaped andreturned home?Would the Seminole Tribe exist the way it is today?Would we be less successful?For these are very intelligent people. A joke I usedto say around them is, “The dumbest person in thePolly Parker family is a genius.” Sometimes the smartbrains don’t fall too far from the apple tree, as theysay. In this case it is very true: Some very intelligentpeople came from Emateloye. Polly’s daughter LucyTiger begat Lena Morgan who had eight children:Hattie Bowers, Tom Bowers, Lottie Shore, MildredTommie, Dick Bowers, Andrew Bowers Sr., Joe Bowersand Casey Bowers.The offspring of Lena Morgan include former TribalChairman Howard Tommie, former Tribal PresidentRichard Bowers, former Tribal Board RepresentativePaul Bowers, Councilman Andrew J. Bowers Jr., formerTribal Secretary-Treasurer Dorothy Scott Osceola,former Health Director Elsie Bowers, Cultural DirectorLorene Gopher, Gaming Commissioner Truman Bowers,former Tribal Clerk Mary Jane Willie, Governor’s CouncilLiaison Stephen Bowers, Secretary’s AdministrativeAssistant Wanda Bowers, Tribal Genealogist GenevaShore, Seminole Craft Artist Nancy Shore, CulturalEvents Specialist Lewis Gopher, Chairman’s SpecialAssistant Norman “Skeeter” Bowers and Tribal GeneralCounsel Jim Shore. Hattie Bowers died as a child andboth Tom Bowers’ children died young: Leon was a16Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum Collection (2003.15.49)

high school graduate studying veterinary medicineand Carol was a Community Health Worker for theSeminole Tribe.One of Polly’s great-great-great-grandkids, GloriaWilson, has had many Tribal positions and is now ourDirector of Community Planning. Another, Paula BowersSanchez, is a professional singer, health educator andis married to our Tribal President. A great-great-greatgreat-grandchild, D’Anna Osceola, is a recent MissSeminole. Four generations from Polly Parker, theycontinue to honor the family tree with quite a fewmore graduating from high school and, even better,from college. Yes, a very significant family in our Tribe.You hear about Osceola. You hear about Micanopy. Youhear about Wildcat and all their great deeds, but youdon’t really hear about the women too much. Andhere is a Seminole woman in our modern times whoperformed this heroic feat in escaping and comingback home, where she continued her Clan of the Bird.The family spread and went on to marry other clans,but they are all related to Emateloye.This is all very important to me. Back in earlier dayswhen I was flying my airplane and going to Tallahassee,there was a VOR (VHF Omnidirectional Radio) rangetransmitter at Egmont Key, just off the Gulf Coast inSt. Petersburg. It gave out a radio signal so you cantrack where you are when you are flying through theair. I always thought of the many Seminoles, includingBilly Bowlegs, who were put in the stockade there onEgmont and then shipped north on the Grey Cloud.Egmont Key is a very important part of our Seminolehistory. I’d like to have Andrew J. Bowers Jr., JimShore and all Polly’s living descendants visit theEgmont Key deportation center, then take the 100mile boat trip all the way up to St. Marks. And standthere where she escaped to make it all the way backdown to her home – more than 340 miles away – tostart a family.I would love to have a picture of the family standingright at the spot where the Grey Cloud left with thisheroic woman not knowing what the future held, herdestiny totally in doubt.As it turned out, Emateloye’s destiny was to start theSeminole Tribe as it is today. By James Billie (Bird Clan)This article originally appeared in theJuly 26, 2013 issue of the Seminole Tribune.Descendants of Polly Parker visited Egmont Key on November 17, 2017. From left to right: Kenny Tommie (Bird Clan), Nancy Willie(Bird Clan), Lewis Gopher (Snake Clan), Bobby Lou Billie (Panther Clan), Gabriel Tommie (Bird Clan), and Aaron Tommie.Photo by Justin Giles, (Tiger/Big Cat Clan, Muscogee (Creek) Nation).17

The RemovedEgmont Key represents the intersection of the historyof two proud Tribes. The handful of Seminole whomanaged to survive their internment on Egmont Keyand later escaped to remain in Florida helped shape thefuture Seminole Tribe of Florida. Those who survivedtheir internment and subsequent removal to the IndianTerritories helped shaped the future Seminole Nation ofOklahoma.In December of 2017, Theodore “Ted” Isham, HistoricPreservation Officer for the Seminole Nation of Oklahomaand member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation – Wind Clan,visited Egmont Key for the first time. Over the interveningmonths Mr. Isham has had time to reflect on his journeyto the island and on its history and its prospects for thefuture. Some of his thoughts (TI) are reflected below inhis response to questions posed by THPO ArchaeologistMaureen Mahoney (MM).MM: What were your first impressions of that island andkind of the history with it?TI: Realizing the importance and the history that it has forthe Seminoles, and especially for the Seminoles that wereremoved. I had a very good, very significant feel because ofthat important history. And because of the fact that it wasan internment site it makes me think of all of the storiesthat people had, or have maybe even down to today, thatare preserved. Stories of being detained there and whatthose might look like, thinking about some that thoughtof running or escaping somehow. So, my thoughts werealong those lines, how sacred that space is for us, for boththe sides of the remaining Seminole peoples both here inFlorida and back in Oklahoma.MM: You had shared one story about people walking intothe ocean, could you share that again?TI: I was looking to find someone who can corroborate itbesides me, I haven’t done the search in an in-depth manner,but we made a plea on Facebook and I got no one to respondabout the story. I’m hesitant to put something down for thefact that I would like to verify that someone else had heardthat same story before I commit to it. So, the story that Ihad been told to me, and I cannot remember who told itto me, but as we know the Creeks and the Seminoles areso intertwined that it’s hard for us with the modern lensto separate which was which. So that the story may haveactually come from the Creeks is a possibility, but afterseeing the island and knowing the history surrounding it, Idoubt that it is Creek, mainly because it fits exactly withwhat Egmont Key as we see it today represents.Anyway, so it’s the idea of being forced away for whateverreason and we see that towards the end of the ThirdSeminole War the U.S. Army being pressed to end thehostilities, resort to capturing the women and children.And the Army would then capture the family to coerceand force the warriors to give up. They would capture theleaders by holding their families on that island, makingit all the more poignant and disturbing that the womenand children were used against their own men folk. I canimagine the sadness and the hopelessness of the situation.They’ve been hiding out all this long time, some 46 yearsin the Everglades and staying elusive. So now we see thatthe families are being captured and their warriors will beallowed to be captured because of that. That wasn’t a goodsituation at all, you know, like backs up against the wall/between a rock and a hard place.Delegates from 34 tribes in front of Creek CouncilHouse, Indian Territory.Photo obtained from the National Archives,photographer unknown.18That’s how I view it. It’s not a very big stretch for me tosay that after all of those years of being fighters and hidingand doing things like that, and doing the things they had todo to survive to that point, I don’t imagine that decidingnot to go any further was a viable option. So en masseas the story has been told, whatever en masse might be,maybe one community, one family, whatever, they decidedto just walk off (into the Gulf waters) instead of beingtaken away from their homelands. Torn away from thehomeland, I guess, is what I would say. So anyway, that’s

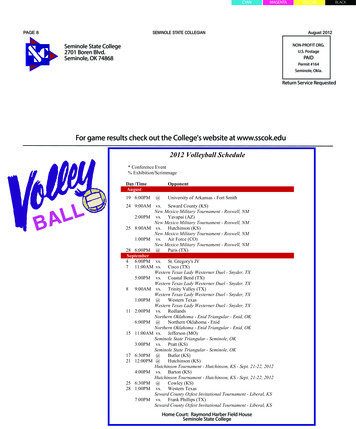

how I would write that if I feel a little bit more comfortable withthe corroboration of the story.MM: What should happen to the island since it will soonbe submerged?TI: If it was a temporary kind of event, that is if the island wereto recover out of the ocean, even temporary means within acouple of lifetimes, we could think about doing something, but Ithink some of these changes that are happening are so long termthat it could (be) a thousand of years before it returns. Maybe,more. And so, thinking about one thousand years is a long, longtime and we do not know what will be available to us to helpremember. I think our best bet is to not try to circumvent whatnature is doing right now, even though we humans have causedit. And just let it go back into the sea even as there may comeplans to try to ‘save’ the island by adding more and more sand.So, commemorating the island for that vision of maybe in athousand years, where would the island be, in our collectivetribal memory, in the record books, and will we be able to findthat information and continue the remembrances of those whohave gone on? Commemorating it by placing the story into thecyber world, or documenting it via a written account, wouldbe the best bet. But, up until that moment, we should make itmore known, if that’s a term. To help educate the people todayabout our histories, our shared histories. And what that meansto us today. We can go far as we can until the island disappearsby continually coming to this place. That time then would beunfortunate, as it’s starting to make that disappearance, like weknow it’s doing now, we will remember that there was disease,there was death on the island, and there was sadness. Andso, it would be good to do a repatriation, a commemoration,or locating and then re-locating of these burials that havehappened on this island. A repatriation onto the mainland ofwhatever remains we may find there will be the best honor thatwe can give to these ancestors who are left here on this island.MM: What are the other ways we can tell the story of Egmont?TI: You mean telling what Egmont is and educating the publicabout what Egmont is? One thing that we did a couple ofsummers ago when I was doing that work, and I still haven’tfinished that work, but it’s almost done, it’s relating the removalroutes, or the removal itself, and what happened within each ofthe routes. The routes for the removed Seminoles from Florida,would then begin with the internments at Fort Brooke, showingthe significance of Fort Brooke in Tampa (a U.S. Army facilityused during the Second Seminole War in part to hold capturedand surrendered Seminoles. Many Seminoles died while incaptivity there). Egmont Key as a hold over and staging place,and then on to Fort Pike and Jackson Barracks (both locatednear New Orleans, Louisiana) as another stopover place of theRemoval. And just by making that route and stories as familiarto the modern people as possible the events of that time will becarried to the future. The list to the right named all of the Seminole whoboarded the Grey Cloud on the final removal voyagefrom Egmont Key. It was originally published in theNew York Herald on May 27, 1858.19

When you leave out Egmont Key you leave out a part ofhistory. you’re not telling the whole story.Egmont should be at the forefront.- Chief Justice Willie Johns, Wild Cat ClanAll history on that island isI heard a lot aboutSeminole history.- Manuel Tiger, Wind ClanEnko-taan-choo-beSeminoles that were captured. I think we can’t lose the history of thisplace and we need to remember places like Egmont Key so that kids knowand thewhat we went through and how we lived during the wars. We need to keep talkingabout this history so we don’t lose it.- Bobby Henry, Medicine Man, Otter Clan20

I was more concerned about trying to protect it. Trying tolearn what we canfrom it, because in the normal ebb and flow of human civilizations, you know whenyou have torebuild, it’s best to know what they tried in the past, so youdon’t end up making up the same mistakes again.- Big Cypress Board Representative Joe Frank, Panther ClanHistory isgood. Get some of it, and holdonto it for our kids.- Billie Walker, Panther ClanThey lookeddeath right in the face, every single day. You know?To be caged up or put on an island where they really can’t move about freely, and bethemselves is I can’t even explain

The Seminole Wars were a part of these large-scale efforts to remove Native Americans west. Seminole elders have shared stories passed down to them of the experiences their ancestors lived through during those dreadful periods in Seminole history. Egmont Key was used as an internment camp to hold imprisoned Seminoles before they 2 Carrying The .