Transcription

History of Sociology at theUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison

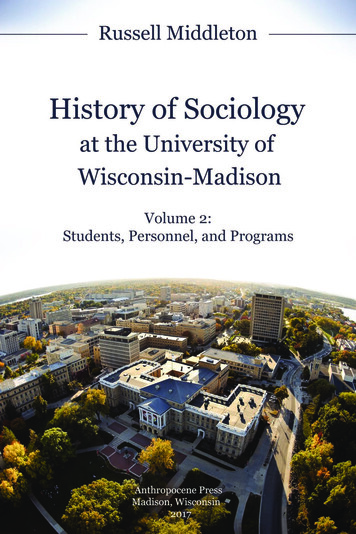

History of Sociology at theUniversity of Wisconsin-MadisonVolume 2Students, Personnel, and ProgramsRussell MiddletonProfessor Emeritus of SociologyUniversity of Wisconsin-MadisonAnthropocene PressMadison, Wisconsin2017

Copyright 2017 by Russell MiddletonAll rights reservedAnthropocene PressMadison, WisconsinBook Cover Design by Tugboat DesignInterior Formatting by Tugboat DesignVol. 2 ISBN: 978-0-9990549-1-8Library of Congress Control Number: 2017908418Front cover, vol. 2: Air view of Bascom HillPhoto by Jeff Miller, University of Wisconsin-MadisonPublisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication dataNames: Middleton, Russell, author.Title: History of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, volume 2 : students , personnel , and programs.Description: Includes bibliographical references. Madison, WI: Anthropocene Press,2017.Identifiers: ISBN 978-0-9990549-1-8 LCCN 2017908418Subjects: LCSH University of Wisconsin—Madison. Department of Sociology. University of Wisconsin—Madison—History. Sociology—Study and teaching—History—United States. BISAC EDUCATION / Higher EDUCATION / Organizations& Institutions HISTORY / United States / State & Local / Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS,MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI)Classification: LCC LD6128 .M54 vol. 2 2017 DDC 378.775/83—dc23

C O N T E N TSVolume 2 Students, Personnel, and ProgramsChapter 1: Graduate Education1Chapter 2: Graduate Student Voices40Chapter 3: Undergraduate Education94Chapter 4: Teaching and Service120Chapter 5: Classified or University Staff and Academic Staff142Chapter 6: The Social Systems Research Institute (SSRI)167Chapter 7: Demography and Ecology and the WisconsinLongitudinal StudyThe Center for Demography and Ecology183183The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study and SocialStratification Research210Center for Demography of Health and Aging220The Applied Population Laboratory227Chapter 8: Computing, Methodology, and Survey Research230Computing and Quantitative Analysis230Methodology239Survey Research251Chapter 9: Early Training Programs—Medical Sociology,Law and Society, Economic Change and Development257Medical Sociology and Health Services257Law and Society273The Sociology of Economic Change and Development287Chapter 10: Social Organization, Class Analysis, andEconomic SociologySocial Organization321321Class Analysis and Historical Change and the A. E. Havens Center 332COWS, Economic Sociology, and New Parties340

Chapter 11: Selected Subject Areas—Gender, Race, and Sports357Gender Studies357Race and Ethnic Studies364The Sociology of Sport421Current Research and Interest Areas of the Faculty437Other Centers and Institutes440A Final Word441References443Appendices515Appendix A: Sociology Faculty Outside the College of Agricultureand Life Sciences, 1874—2016517Appendix B: Sociology Faculty in the College of Agricultureand Life Sciences, 1911—2016529Appendix C: Wisconsin PhDs Granted in Sociology, 1909-2016533

This is a continuation of Volume 1 of the History of Sociologyat UW-Madison. Volume 1 contains: The story of John Bascom, President of UW, 1874-1887, progenitorof “The Wisconsin Idea, and first person to teach sociology at UW Richard T. Ely, economist-sociologist who built UW as a leading center for social science at the turn of the 20th century. His “heresy trial”led to the Regents’ “sifting & winnowing” declaration. John R. Commons, a sociologist who became the leader of the institutional economists at UW—but tainted by racism, like many progressives of the period E. A. Ross, a progressive economist who shifted to sociology after being fired at Stanford. A pioneer in social psychology and social control. A crusader for academic freedom and a fearless public intellectual who was probably the world’s most famous sociologist between1900 and 1930. Also tainted by racism in his early years. Other famous early sociologists, including John L. Gillin, KimballYoung, and Samuel Stouffer C. J. Galpin, the chief founder of rural sociology, human ecology, andempirical research at UW, and John H. Kolb, the founder of the Department of Rural Sociology Anthropology in the department in the 1930’s: Ralph Linton andCharlotte Gower The intersecting lives and conflicts of C. Wright Mills, Don Martindale, Hans Gerth, and Howard P. Becker The enigmatic personalities of Hans Gerth and Howard P. Becker,and the latter’s disruptive influence in the department The movement toward interdisciplinary research organizations inAmerica, and Wisconsin’s failed efforts to create such units and attract foundation funding The declining reputation of UW Sociology in the 1930s to 1950s, andthe lack of research funding for the social sciences by the UW administration, government agencies, and private foundations. Wisconsin Sociology’s turnaround between 1958 and 1980, initiatedby William H. Sewell and carried forward by many others Rural Sociology’s growth, reorientation, and renaming as Community and Environmental Sociology Attacks on civil liberties and academic freedom Wisconsin student protests and demonstrations, 1960-1974 Political threats to UW and Wisconsin unions, 2010-2016

C H A PT E R 1Graduate EducationPhDs and Master’s Degrees GrantedWisconsin sociologists have contributed greatly to the discipline of sociology, not just through their research and publications, but through the education and training of new professional sociologists. Since the first graduatedegree in sociology was granted in 1909, 1133 persons have earned PhDsand 1595 have completed master’s degrees. (See Table 8.) The University ofWisconsin has had one of the larger programs since the early days of the discipline, and its graduates are widely spread throughout the land and abroadin universities and government agencies.Table 8. PhDs and Master’s Degrees Granted, 1909-2014YearsPhDsMaster’s -201615094Total Years11331595SOURCES: GILLIN, N.D., “HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEPARTMENT OFSOCIOLOGY,” (UW ARCHIVES 7/33/4, BOX 18); UW SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT FILES.1

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2Ross and Gillin were the principal self-identified sociologists in the department during the early years when the Department of Political Economystarted offering PhDs and master’s degrees in sociology, though Ely andCommons also played important roles and sometimes asserted their identity as sociologists. During the first eleven years between 1909 and 1919, onlyseven PhDs and 20 master’s degrees were granted in sociology, but duringthe 1920s the production of PhDs quadrupled. They increased another 25percent in the 1930s and reached a new high of seven per year in 1940 and1941. Then with the start of World War II the numbers fell sharply whilemany young men were in the armed forces, but they recovered in the late1940s and averaged about six per year in the 1950s and early 1960s.There was a sharp turn upward starting in 1966, when 13 PhDs weregranted, and the number has been in double figures every year since then.I suspect that the explosion in numbers in the late 1960s and 1970s was aresponse to the social activism of the 1960s—the Civil Rights Movement,the Peace Movement, the Women’s Rights Movement, the EnvironmentalMovement, and movements for the rights of various minority groups. Therewas a spirit of idealism that led many college students to turn to sociologyas a vocation that might also permit them to address their social concerns insome way. Because there is a lag of several years between entering a graduate program and completing a degree, the peak year for sociology PhDs atWisconsin was 1973 when 30 were granted, and for master’s degrees 1970,when 51 were completed. Though the University of Wisconsin was one of thecenters of activism in the 1960s and had a reputation as a liberal campus,similar things were happening across the nation. The 1970s representeda high-water mark for the granting of PhDs in sociology nationally, with1975-76 representing the peak with 729 granted (National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 325.92). The numberof PhDs and master’s degrees declined somewhat at Wisconsin in the 1980sand a little more in the 1990s, then nosed down sharply in the 2000s. Theyearly production of PhDs has increased sharply again since 2010, but master’s degrees have continued to decline slightly.The 1130 PhDs awarded by the University of Wisconsin in sociology nodoubt constitutes a significant portion of the total number of sociology PhDsproduced by American universities. How does the Wisconsin departmentcompare with other leading departments? The National Science Foundationhas done annual surveys of sociology PhDs awarded in the United Statessince 1966. I am not aware of any studies of the accuracy of the surveys,which, like all similar surveys, depend on the record-keeping, cooperation,and diligence of personnel at a great many reporting units. Their figuresby department have not yet been published, but with the help of MichaelKisielewski and the research staff at the American Sociological Association,2

Graduate EducationI have been able to download the relevant data from the WebCASPAR database. The NSF sociology data by department for the period 1966 to 2011are shown for the forty largest programs in Table 9. During this period 182different American universities granted at least one PhD in sociology, butthe 55 smallest programs produced only 148—less than ten each—constituting only 0.6 percent of the total. Even the smallest 100 programs producedonly 3188—less than 130 each—and made up only 12 percent of the total.The forty largest programs produced 15,344 PhDs, representing 60 percentof the total of 25,710. In the first ten-year period of the NSF surveys, theyproduced 70 percent, but the figure has fallen to 54 percent since 1996.Table 9. Sociology PhDs Produced, by Forty Largest UniversityPrograms, 520062011Total,19662011University ofWisconsin-Madison171196168171105811University ofChicago18420910915180733University ofCalifornia-Berkeley17716315313897728University of Michigan at Ann Arbor13116312114568628Cornell University,All Campuses1481511028162544Ohio State University, Main Campus133130858895531University of Texasat Austin8210510515087529University of California-Los Angeles134918713379524Columbia University, City of NY165125608162493University ofPennsylvania7011311511468480CUNY Graduate Sch.& Univ. Center1112211912176449Harvard University99110782614203

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2Michigan StateUniversity115102857333408University of Minnesota-Twin 949376Univ. of North Carolina-Chapel Hill8187757254369New York University98101474755348Stanford University6371797554342Pennsylvania StateUniv. Main Campus6160628468335University of Southern California7883677037335Washington StateUniversity80110545333330Indiana Universityat Bloomington7267518451325University ofWashington-Seattle7465597146315Iowa StateUniversity6959926029309Brown University5083716833305University of Colorado at Boulder6285377033287New School forSocial Research6453447351285Univ. of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign8364534933282Johns HopkinsUniversity5858647130281Yale University7074594332278University of Missouri, orida StateUniversityBoston University4

Graduate EducationPurdue University,Main Campus7055535129258University of Oregon856444032257Rutgers, State U. NJ,New Brunswick27110434828256Princeton University5142515355252Univ. of Maryland,College Park3247516754251Univ. of California-Santa Barbara3260445952247Brandeis University5378484518242Total for 40 LargestPrograms350737212906313220781534440 Largest Programsas % of tal for all 182ProgramsSOURCE: NSF SURVEYS OF EARNED DOCTORATES, 1966-2011, NATIONAL CENTERFOR SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING STATISTICS, DATA DOWNLOADED FROM THEWEBCASPAR DATABASE, COURTESY OF THE ASADuring the 1966-1975 decade the University of Chicago and the University of California-Berkeley granted more sociology PhDs than Wisconsin, but the Wisconsin program was growing rapidly. The Chicago programreached a peak during the next decade and was still larger than the Wisconsin program, but after that the Chicago program and most of the otherdepartments with high prestige rankings began to decline in PhDs granted,while the Wisconsin production has remained stable at a high level since1986.Though Wisconsin has granted the most PhDs in sociology since 1966,it is well known that the University of Chicago and Columbia University,where the first two departments were founded, were dominant in the discipline during its early days. If Columbia was playing second fiddle to Chicago, Wisconsin was at best a “third fiddle.” Published figures for sociologyPhDs by department tend to be absent or fragmentary for the early decadesof the discipline. In 1932, however, the Association of Research Librarieswas founded by 42 major university and research libraries, and it began topublish an annual series of Doctoral Dissertations Accepted by AmericanUniversities, with authors’ names, titles, fields, and university affiliations. Itcompiled information going back to 1925, and its figures were republished5

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2periodically in the American Council on Education’s volumes, AmericanUniversities and Colleges, beginning with its third edition in 1936. Assembling parts of tables from the third to the tenth editions yields informationabout the granting of sociology PhDs from 1925 to 1966, which links closelywith the NSF series starting in 1966. The ACE tables have some overlappingyears, but the annual volumes published by the Association of Research Libraries can be used to eliminate the overlaps except for the last period, 19571966. The years 1957, 1958, and 1966 are double-counted, thus inflating thefigures for the last period. The ACE-ARL figures for the 20 largest programsin the NSF surveys, plus Yale, which played a substantial role in the earlierdecades, are shown in Table 10.Table 10. Sociology PhDs Granted by Selected Universities, ACE-ARLStatistics, 1925-1966UniversityPhDs Granted, ACE-ARL niversity of Chicago9180158122451University ofWisconsin-Madison44504852194Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley57244278University of Michigan25173132105Columbia University62618917229Ohio State University22265370171Cornell University21265440141Harvard Univ. & Radcliffe43383054165University of Pennsylvania23172833101University of Texas15102238Univ. of Calif.—Los Angeles000272724217454173414362110University of Minnesota24112762124New York University14493560158Univ. of Southern California22254248137000001011152359Univ. of North CarolinaMichigan State UniversityCUNY Graduate SchoolNorthwestern University6

Graduate EducationYale University3724Stanford University4Pennsylvania State Univ.1613Total sociology PhDsgranted by all URCES: AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION, AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES &COLLEGES, EDITIONS 3, 4, 6, 8, 10; ASSOC. OF RESEARCH LIBRARIES, DOCTORALDISSERTATIONS ACCEPTED BY AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES, 1948, 1949As expected, Chicago awarded the most sociology PhDs throughout the1925-1966 period—almost twice as many as any other university. Columbiaproduced the second most PhDs, reaching a peak in the 1949-1958 period.Wisconsin was in third place for the period as a whole, though it was slightlybehind Cornell in 1949-1958 and Harvard in 1957-66. Chicago, Columbia,and Wisconsin were trailed by several universities grouped closely togetherbetween 150 and 173 PhDs: North Carolina, Ohio State, Harvard-Radcliffe,New York University, and Yale. Michigan State, Berkeley, Penn State, Stanford, Texas, and UCLA produced relatively few PhDs before the 1960s, andthe CUNY Graduate School produced none.The data from the Association of Research Libraries did not cover thefirst four decades of the discipline, but I found one source that purported tocover the entire period between 1893 and 1965. Lunday (1969) compiled abibliography of 3993 sociology dissertations, which he claimed representedall of the sociology dissertations completed in the United States between thefirst one in 1893 (at the University of Chicago) and 1966. He compiled thelist from numerous indexes and bibliographic sources and sent his tentativelist to each of the granting departments for verification and corrections. Itabulated the number of dissertations listed in the bibliography for a number of the larger programs. In checking his listings against the Universityof Wisconsin records, I found them to be quite accurate for the years between 1934 and 1965, a period when the Association of Research Librarieswas compiling information about dissertations, but the bibliography washighly inaccurate for the earlier period. He missed all 14 of the sociologydissertations completed at Wisconsin between 1909 and 1922, and 29 out ofthe first 52 dissertations written by 1933. The bibliography appeared to beinaccurate for the other universities as well and actually showed a smallernumber of dissertations produced for the entire 1893-1965 period than didthe ACE-ARL records just for the 1925-1966 period for some of the universities. I have not been able to locate accurate figures for the period from 1893to 1925—the period when Chicago and Columbia were most dominant inthe field.7

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2Combined ACE-ARL and NSF data are presented for the entire 19252011 period in the last column of Table 11. One must keep in mind, however, that the ACE-ARL figures are somewhat inflated by three overlappingyears, and the years from 1893 through 1924 are totally missing. Wisconsingranted 18 sociology PhDs before 1925, and Chicago and Columbia almostcertainly produced a great many more, though I have not found an accurate record for them. The totals in the last column still show Chicago as theleader in the production of sociology PhDs, and its lead would probably beeven more pronounced if figures for the period before 1925 were available.Wisconsin is in second place because of its greater production from 1966 to2011.Berkeley started slowly, but it added many distinguished senior professors in the 1950s and 1960s and became a major center for graduate education in sociology. The Berkeley and Michigan programs both grew robustlyand now are in third and fourth place, ahead of Columbia. Columbia’s production has diminished since the 1980s, but its numbers would certainly behigher if one included PhDs awarded before 1925. Ohio State and Cornellhave been consistent granters of PhDs and are in sixth and seventh place,just ahead of Harvard, which has also tailed off in recent decades.Table 11. Sociology PhDs Granted by Selected Universities,ACE-ARL Statistics, 1925-1966, and NSF Surveys 1966-2011ACE-ARLData1925-1966NSF Data1966-2011GrandTotal1925-2011University of Chicago4517331184University of Wisconsin1948111005Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley78728806University of Michigan105628733Columbia University229493722Ohio State University171531702Cornell University141544685Harvard Univ. & Radcliffe165420585University of Pennsylvania101480581University of Texas38529567Univ. of Calif.—Los Angeles27524551173369542Univ. of North Carolina8

Graduate EducationMichigan State University110408518University of Minnesota124389513New York University158348506Univ. of Southern California137335472044944959376435CUNY Graduate SchoolNorthwestern UniversityYale University150278428Stanford University44342386Pennsylvania State Univ.4533538044442571030154Total sociology PhDs grantedby all universitiesSOURCES: AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION, AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES &COLLEGES, EDITIONS 3, 4, 6, 8, 10; ASSOC. OF RESEARCH LIBRARIES, DOCTORALDISSERTATIONS ACCEPTED BY AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES, 1948, 1949; ANDWEBCASPAR DATABASEThe peak of PhD production at UW-Madison occurred in 1976-1985,at a time when little consideration was given to whether immediate funding of admitted graduate students was available. Since then the numbersof students admitted and completing the PhD program have declined, asthey have at most other universities in the country. In recent years therehas been a growing concern about the increasing cost of higher educationand the growing debt burden of graduates. A tightening job market for newsociology PhDs has also led many to believe that there is an overproductionof new PhDs. The Wisconsin sociology faculty debated whether they shouldadmit only those students for whom they could guarantee funding for fiveyears through traineeships, fellowships, and assistantships. They voted todo so in 2012, and the entering cohort of graduate students in Fall, 2012,numbered only fourteen.Some have raised questions about the policy, pointing out that a largenumber of very able students had been admitted in the past without immediate or guaranteed funding, and they believed that the new policy wasexcessively paternalistic in denying able students the choice of comingwith self-funding, taking on substantial debt, or taking a chance on gettingfunding later in the program. Reducing the number of enrolled studentsalso affects the department’s share of state funding according to the statefunding formula, resulting ultimately in a reduction in faculty size. It is alsodifficult to estimate the acceptance rate of those who are admitted, and thereis always the danger that too few students will be admitted to fill vacant9

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2teaching assistant slots or sufficient enrollment for seminars in some fields.The number of entering graduate students increased from 14 in 2012 to 19 in2013 and 23 in 2014, but in 2015 it fell to 13. Regardless of what target is set,the outcome is always unpredictable. The top sociology departments are allcompeting for the most promising students, so most of the highly qualifiedapplicants have multiple offers from which to choose. Even with a guaranteeof five years of funding, in 2015 three out of four of those admitted to theWisconsin sociology program rejected the offer. In 2016 there were 263 applicants and the admissions committee admitted 67, anticipating that therewould probably be about 18 acceptances. The acceptance rate for 2016, however, turned out to be 53 percent, more than double the acceptance rateof the previous year. Thus, 36 students joined the 2016 cohort—double theintended target of 18. In 2017 the number of applicants increased to 280,but because of the 2016 overshoot, the admissions committee set a target of10 for the 2017 cohort and initially admitted 24—20 from the U.S. and oneeach from the United Kingdom, Germany, China, and Korea.First Sociology PhDsTheresa Schmid McMahonThe very first PhD in sociology at the University of Wisconsin was awardedin 1909 to Theresa Schmid McMahon (1878-1961), an outspoken feministand labor activist student of John R. Commons. There is little publishedinformation about most of the early students, but we are fortunate to havea 61-page autobiography entitled My Story that McMahon wrote in 1958,twenty-one years after her retirement from teaching at the University ofWashington (McMahon, 1958). She was asked by Henry Schmitz, Presidentof the university from 1952 to 1958, to write a history of her experienceswith the university as a student and a professor. She commented, “PerhapsDr. Schmitz had the idea that if I wrote of my experiences there might bewritten a real history of the University. I am not sure, because I think everyhistory is largely a biography of the writer” (Ibid., p. 1). She was then 80years old, blind, and in failing health from crippling arthritis. She had noaccess to any written records, but she recounted her memories into a Dictaphone and copies of the transcript were made with a spirit duplicator. Shesaid that she did not expect her recollections to be published or circulatedbeyond her former students, and she did not hesitate to “wash the university’s dirty linen” in her account. Original dittoed copies can be found in theUniversity of Wisconsin Memorial Library collection and in the Universityof Washington archives. Later Howe published the entire autobiography inLone Voyagers (Florence Howe, 1989, pp. 238-280).10

Graduate EducationTheresa Schmid was born in Tacoma, Washington, in 1878 but grewup on Mercer Island, at that time a largely unpopulated island just offshorefrom Seattle in Lake Washington. Her father homesteaded there when therewere few people, but today it is largely urbanized. According to the 1930U.S. Census, her father was born in Germany, but her mother was American. She had relatively few friends her own age, and her mother died whenshe was twelve, so she did not have a traditional feminine upbringing. In herautobiography she mused,. . . About the only outstanding characteristic I really possessed, and itwas one that remained with me all the rest of my life, was an absenceof fear—people having interpreted it as courage. I didn’t have courage;I simply didn’t know what fear was. I wasn’t afraid of the lake; I wasn’tafraid to ride bareback through the woods on cowtrails. . . . I never wasone to follow the beaten path, even as a child. My brother once said tome, “You think So-and-So is a queer girl?” “Yes.” “Do you realize youare a freak?” I was a freak. I was different from other women, but whenyou realize that I had none of the feminine background or training, thatI just grew up like Topsy, it is easily understood why I was a rebel andstill am (McMahon, 1958, pp. 1-2. 51).Theresa attended only an ungraded school on the island and had nohigh school education. Nevertheless, she entered the University of Washington’s sub-freshman class in 1894 at the age of 16 and graduated in 1898.Though she majored in English and took a master’s degree in English, shediscovered social science when the economist J. Allen Smith joined the faculty in 1897. Smith had been trained at the University of Michigan by HenryC. Adams, who had been a student of Richard T. Ely at Johns Hopkins andhad imbibed heterodox economic ideas from him. Under Smith’s influenceMcMahon began to concentrate almost entirely on the social sciences, particularly sociology. She recalled, “I don’t think that I had any special inclination or leaning toward economics or political science, but I did towardssociology” (McMahon, 1958, p. 9). This is remarkable, since there was nosociology department or any formally trained sociologist at the Universityof Washington at that time.McMahon was greatly influenced by Herbert Spencer’s ideas aboutevolution, but perhaps even more by the work of the pioneer American sociologist Lester F. Ward. Dimand (2000, p. 304) says that McMahon wasalso influenced by the feminist writings of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, thoughshe did not accept Gilman’s racist and nativist ideas. Perhaps she was influenced later in her career, but her own dissertation was written threeyears before Gilman published The Man-made World, or Our Androcentric11

History of Wisconsin Sociology, vol. 2Culture (1911), which expressed ideas similar to those of McMahon. Threeof Ward’s books appear in McMahon’s references in her dissertation, butGilman is nowhere mentioned. Actually, Ward’s “Gynaecocentric Theory”arguing the primacy of the role of women in evolution was probably a majorinfluence on both. Ward wrote that “the female sex is primary and the malesecondary” in both biological and social evolution. In the early developmentof human society females ruled, but gynaecocracy was eventually succeededby a stage of androcracy and the complete subjection of women:Throughout all human history woman has been powerfully discriminated against and held down by custom, law, literature, and public opinion.All opportunity has been denied her to make any trial of her powers inany direction (Ward, 1903, p. 377).Ward was virtually alone among male social scientists in advancingthese views, and it is not surprising that his theories struck a responsivechord in both McMahon and Gilman. Gilman dedicated one of her books toWard in perhaps the most effusive, hyperbolic dedications ever written inthe social sciences:This book is dedicated with reverent love and gratitude to Lester F. Ward,Sociologist and Humanitarian, one of the world’s great men; a creativethinker to whose wide knowledge and power of vision we are indebtedfor a new grasp of the nature and processes of Society, and to whom allwomen are especially bound in honor and gratitude for his Gynaecocentric Theory of Life, than which nothing so important to humanity hasbeen advanced since the Theory of Evolution, and nothing so importantto women has ever been given to the world (Gilman, 1911, p. 2).The person who played the greatest role in helping McMahon to find herradical political philosophy and turn her into a crusader against economicinjustice was J. Allen Smith while she was still a student at the University ofWashington.I worked with J. Allen Smith for two years and at the end of that time Inot only understood monopolies but I hated them. I hated the injusticethat occurred in the industrial fields: the exploitation of common resources by the few and the exploitation of the workers, many of whomwere ignorant foreigners too helpless to remedy their lot. It was a foregone conclusion that the men of wealth accepted their financial statusas due wholly to their ability, with perhaps a little assistance from theAlmighty (McMahon, 1958, p. 10).12

Graduate EducationSmith himself and two colleagues had been fired at Marietta College inOhio by a conservative board dominated by Charles G. Dawes for supporting Wil

Photo by Jeff Miller, University of Wisconsin-Madison Publisher's Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Middleton, Russell, author. Title: History of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, volume 2 : stu-dents , personnel , and programs. Description: Includes bibliographical references. Madison, WI: Anthropocene Press, 2017.