Transcription

A ROADMAPFOR LINKAGEAligning Californiaand Washington’sCarbon PricesJULY 2022

CONTENTS2Background on Carbon Pricing inCalifornia and Washington3Formal Linkage and IncrementalAlignment4Coordination Between Californiaand Washington5A Roadmap for Alignment and Linking6Conclusion13Endnotes14

01BACKGROUND“MORE THAN 65 CARBONPRICES REGULATE NEARLY22 PERCENT of globalemissions”Carbon Pricing inCalifornia andWashingtonCarbon pricing is an effective approachfor reducing greenhouse gas (GHG)emissions that fuel climate change.Carbon prices are usually implementedthrough a carbon trading or carbontaxation program. Regulators aroundthe world are increasingly deployingcarbon pricing to complement theirexisting policy approaches.1 Currently,more than 65 carbon prices regulatenearly 22 percent of global emissions,a steep increase from previousyears.2 These programs collectivelyraised over 48 billion USD worth ofrevenue in 2019,3 much of which isreinvested into communities that bear adisproportionate pollution burden andthe brunt of the adverse impacts causedby our changing climate. Moreover,recent studies provide evidence thatthese programs also substantially reduceGHG emissions, even when carbon pricelevels are relatively low. 4California and Washington are among thejurisdictions that have chosen to place aprice carbon. California’s cap-and-tradeprogram started in 2013 and is one ofthe largest carbon markets in the worldwith a cap of 200 million metric tons ofGHG emissions in 2020. The programcovers the electricity, transportation,and industrial sectors. The program hasraised over 13 billion USD for the State,557 percent of which has been reinvestedinto disadvantaged and low-incomecommunities.6The California program has taken on agradually more prominent role in thestate’s climate policy mix. In its initialiteration, regulators designed theprogram to achieve roughly 10 percentof the state’s 2020 climate target.7 Inthis context, the role of the programwas primarily to serve as a backstop,dynamically ramping up abatementif any of California’s numerous otherclimate emission reduction policies,which were slated to do the heavy lifting,failed to achieve their intended reductiontargets.8 The initial program iterationserved this role admirably, contributingto the achievement of California’s 2020statewide climate target in 2016, fouryears ahead of schedule.9In the 2017 Scoping Plan, regulatorscarved out a more vital role for theprogram by designing it to achieveroughly 40 percent of the state’smore stringent 2030 climate target.10Compliance entities are now respondingby ramping up demand, resulting inrecent carbon prices just over 30 USDper ton. Under these new circumstances, 48.0BILLION USDCalifornia’s Legislative Analyst’s Officepredicts that the program could raiseup to three billion USD during the 2022fiscal year.11Washington’s nascent cap-and-investprogram originates from the passage ofthe Climate Commitment Act (CCA) inApril 2021, resulting from collaborationbetween local regulated businesses,environmental nonprofit organizations,tribes, and racial equity organizations.The legislation resembles California’scap-and-trade program but also includesnovel features and approaches toprice management, carbon offsetting,and environmental justice. The stateregulator (the Department of Ecology,hereafter referred to as “Ecology”) mustexpeditiously promulgate the programby January 2023. As such, Ecology isin the process of completing severalrulemakings to flesh out the details ofthe program.COLLECTIVE REVENUE GENERATED FROMCARBON PRICING PROGRAMS IN 20193

A ROADMAP Aligning California and Washington’sFOR LINKAGE Carbon Prices02FORMAL LINKAGEand INCREMENTALALIGNMENTAs California’s program continues itsevolution to address new state carbonneutrality goals and Washington’sprogram takes its first steps, it is criticalthat these jurisdictions explore waysto learn from one another and expandtheir collaboration. One approach is toformally link carbon pricing programs byallowing companies in each jurisdictionto buy and retire allowances from theother jurisdiction to satisfy compliancerequirements.12 This is the approachoriginally conceived of by the WesternClimate Initiative—to which Californiaand Washington are both members—andit is the approach California chose to takewith Quebec when they formally linkedtheir programs in 2014.Economists have carefully studiedthe benefits of formal linkage.Fundamentally, formal linkage leads toa single allowance price across all linkedjurisdictions, thereby reducing total coststo final consumers without sacrificingenvironmental benefits.13 In turn,these cost reductions make it easier forregulators to achieve ambitious climatetargets and lower overall cap levels.14One study shows that if cost savings froma formally linked international carbonprice were reinvested into enhancedambition, then countries could doubletheir emissions reductions by 2030.15 Inaddition, formal linkage sends a strongpolitical signal of cooperation on climatechange which, in and of itself, facilitatesenhanced climate ambition. Formallinkage also eliminates competitivenessimpacts across jurisdictions, therebyreducing concerns over emissionsleakage between linked jurisdictions.Aside from environmental benefits,formal linkage offers greater marketcertainty through two pathways. First,the larger number and broader typeof entities that can trade with oneanother leads to improved liquidity andeconomic efficiency. This contributesto program performance by ensuringthat the carbon price accurately reflectsunderlying abatement costs for a widegroup of entities. Second, formal linkagecan dampen carbon price volatilitycaused by regional variations, especiallyif critical factors such as seasonalweather or economic activity areIt is critical that these jurisdictionsexplore ways to learn fromone another and expand theircollaboration.

IF COST SAVINGS FROM A FORMALLYLINKED INTERNATIONAL CARBONPRICE WERE REINVESTED INTOENHANCED AMBITION,COUNTRIES COULDDOUBLE THEIR EMISSIONSREDUCTIONS BY2030imperfectly correlated across jurisdictions.16 This is particularlypertinent to California and Washington, where electric loadspeak at separate times.While the value of formal linkage is quite significant, there areat least two challenges with formal linkage. First, carbon pricesthat are not formally linked from the beginning will inevitablybe designed differently. Some of these design differencesneed to be addressed before a formal link occurs to ensuresmooth joint functioning of the linked program. The ensuingnegotiations can be thought of as a prerequisite to entering aformal linkage.17 Second, formal linkage can change incentivesin subtle ways that could threaten the environmental integrityof the overall cap, such as incentivizing jurisdictions toartificially inflate their caps. These incentives can be dulledor reversed with smart policy design, with several authorsnoting that formal linkage can enhance overall ambitionby incentivizing more aggressive caps.18 These smart policydesigns are discussed in detail in subsequent sections of thisreport. It is important to acknowledge and account for theseincentives early on to ensure the desired emission outcomesresulting from formal linkage. For these reasons, regulatorsmay find formal linkage a slower process than typicallyanticipated, despite the apparent benefits. The motivation forthis paper is to consider formal linkage that results in moreambitious climate targets by highlighting smart policy designs.A complementary approach is to pursue “linkage by degrees,”which celebrates the incremental alignment of policy designsand implementation strategies between carbon pricingprograms.19 Further harmonizing carbon price designs acrossjurisdictions allows regulators to capture a substantialportion of the economic and environmental benefitstypically associated with formal linkage, without executinga formal linkage. For example, two programs might alignthe level of their price floors, thereby increasing certaintyfor compliance entities and their consumers. In addition,aligned price floors would mitigate, to some extent, concernsover competitiveness impacts and emissions leakage acrossjurisdictions that formal linkage would completely remedy.As another example, a program seeking to link with anotherprogram might align its approach to ensuring that carbonoffsets are of high quality with that of the other program,thereby supporting environmental integrity and bolsteringemissions reductions. These types of incremental alignmentsof policy design, facilitated by the sharing of best practices andearned expertise over time, strengthen the implementationof each carbon pricing program. In addition, such “informal”linkage also smooths the path for formal linkage becauseprogram designs become more alike with progressiveincremental alignment.

A ROADMAP Aligning California and Washington’sFOR LINKAGE Carbon PricesCoordinationBetweenCalifornia andWashington03California and Washington each haverigorous processes to determine whetherto accept another jurisdiction’s programas a formally linked partner. In California,the board of the climate regulator (theCalifornia Air Resources Board, hereafterreferred to as “CARB”) approves linkageafter a finding from the Governor that(among other factors) the programunder consideration for linkage is atleast as stringent as California’s program.Thereafter, CARB must initiate a fullrulemaking process to amend the carbonpricing program to accommodate thenew link. By way of example, in 2013,Governor Jerry Brown directed CARB toundertake a number of additional stepsprior to California’s linkage with Québec,including a linkage readiness report, andCARB undertook a lengthy rulemakingprocess that resulted in a number ofchanges to the program rules.20 InWashington, the CCA contains two setsof requirements. The first requires aformal linkage agreement that addressesa broad range of carbon pricing designfeatures and does not adversely impactWashington’s ability to achieve itsclimate targets. The second relatesto environmental justice, essentiallyrequiring that any linkage agreemententered into by Ecology protect againstadverse effects on overburdenedcommunities in both linked jurisdictions.6These processes mean formal linkagecomes with hurdles in the short-term.Consistent with these short-termchallenges, a representative fromEcology recently stated that “we’renot going to be [formally linking withCalifornia] at the beginning [and] wedon’t know for sure when or if wewill ever be linked”.21 However, bothprograms indicate interest in formallinkage, and have already started layingthe groundwork to be able to do so. Theprograms are already practicing informallinkage by sharing best practices andearned expertise. Ecology has alreadyamended parts of their proposedregulation to mimic CARB’s approachto “support [the] regulatory programand potential linkage”22 and has noticedits explicit intent to “mirror rules from[CARB] for their offset program as soonas possible”.23 In addition, Washingtonrecently signed an agreement for WCIInc. to administer its online auctioningplatform, the same as is done inCalifornia.24 This move allows for easycombining of auctions if a formal linkagewere to be executed.

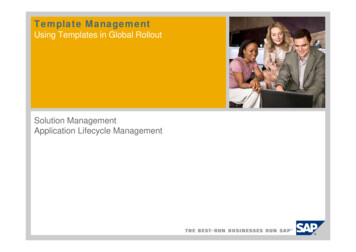

04A ROADMAPFOR ALIGNMENTAND LINKINGA coordinated approach betweenCalifornia and Washington’s carbonpricing programs must move beyond thebinary question of whether to formallylink today. It is impractical to expect twoprograms that started at different times(under unique circumstances and withvarying designs to reflect each states’individual priorities) to be ready to linkat the outset. A pragmatic roadmapwould place formal linkage in its properrole, a longer-term objective that is bestachieved through short-term alignmentsof program designs. This can equally beviewed as both a “no regrets” approach(since aligning program designs offersits own benefit) and as a measuredstrategy for maximizing the probabilityof a successful formal linkage. Speakingto the latter conceptualization, Burtrawet al. (2013) argue that incrementalalignment helps ensure the long-termstability of a formal linkage because it“reduces the prospect of unanticipateddifficulties” in the shared program.25Table 1 evaluates alignment betweenWashington’s developing and California’sestablished carbon pricing programs,adapting an approach taken byBurtraw et al. (2013). Overall, the tablereveals that to date the Washingtonand California programs seem to havealigned some of the major designelements but others need to beaddressed in more depth or reevaluatedin light of linkage considerations.Also, a significant number of designelements receive a designation of “to bedetermined”, given that Washington’srulemaking is ongoing. The mostimportant misalignments (which arehighlighted) fall into five categories:noncompliance penalties; price ceilings;cap setting; allowance allocation toemissions-intensive and trade-exposedindustries (EITE); and carbon offsets.The analysis underlying Table 1 turnson five considerations represented ascolumns and elaborated on in the bulletsbelow. Taken together, the table allowsan assessment of whether Californiaand Washington are ready to executea formal linkage. If a design element isnot important—based on columns twoand three—or if that design element isalready aligned, then we conclude thatthe programs are ready to formally linkbased on that design element. However,if a design element is important but notalready aligned between these programs,then we recommend that Washingtonregulators prioritize these areas foralignment. Design Element: the first columndecomposes a carbon price into tendesign elements that represent thecentral choices each jurisdictions’regulators make when creating aprogram. These elements cover thefollowing topics: technical issues;emissions reduction goal; allocationof allowances; cost management;and enforcement and contingencies.Environmental Integrity: thesecond column analyzes whetheraligning the design element isimportant for ensuring that theenvironmental integrity of bothprograms remains constant orfurther improves under formal linkage.Policy Implementation: the thirdcolumn analyzes whether aligningthe design element is important forreasons unrelated to environmentalintegrity such as distributional,equity, or political issues.Degree of Alignment: the fourthcolumn analyzes whether the designelement is already aligned acrossprograms.Readiness for Linkage: the fifthcolumn analyzes whether programsare ready for formal linkage basedon the design element in question.The remainder of this paper focuses onthree opportunities (listed below) toprioritize incremental alignment. Foreach of these design considerations,we outline differing approaches takenby California and Washington, whythose differences are important, andoptions for aligning design. Whereappropriate, we offer a recommendationon which form of alignment is preferableand outline associated benefits. Bydiscussing these issues in detail, ouraim is to capture short-term benefitsthrough incremental alignment whilesimultaneously facilitating formal linkageas an outcome. This is intended to be aninitial review that is not comprehensivein nature and there are therefore issuesthat we do not discuss that are also likelyto be important to formal linkage. Theremainder of this paper is focused on:a)b)c)Noncompliance PenaltiesPrice CeilingsCap Setting7

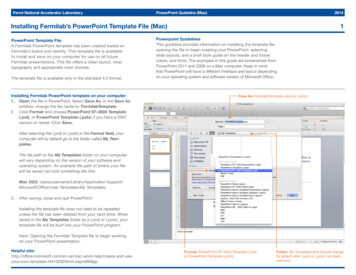

A ROADMAP Aligning California and Washington’sFOR LINKAGE Carbon PricesTable 1Evaluating Alignment Across Washington and California Carbon Pricing ProgramsImportant forEnvironmentalIntegrity?Important for PolicyImplementation?Already Aligned?Ready to Link?a. Measurement methodsYesYesYesYesb. Reporting of process emissionsYesYesYesYesc. Reporting of fugitive emissionsYesYesTBDTBDd. Reporting of emissions fromimported powerYesYesYesYesa. Registries (e.g., serial numbersystems)YesYesYesYesb. Data collection on transactionsNoMaybeYesYesMaybeYesTBDTBDa. Are caps defined in terms of totaltons?YesYesYesYesb. Are cap stringencies coordinated?YesMaybeTBDTBDc. Are programs binding?YesYesYesYesMaybeMaybeNoNoa. Covered sectorsNoMaybeYesYesb. Point of regulationNoMaybeYesYesc. Compliance thresholdsNoMaybeYesYesd. Coverage of imported, fugitive,process emissionsYesYesTBDTBDe. Compliance periodsNoNoNoYesMaybeMaybeMaybeMaybea. Method of allocation to industry EITEYesYesNoNob. Treatment of entrants and exitsNoMaybeTBDTBDc. Use of revenue from auctionsNoMaybeTBDTBDd. Measures to address leakageYesYesTBDTBDDesign ElementTechnical Issues1. Measurement, Reporting andVerification2. Allowance Tracking Systemc. Public access to dataEmissions Reduction Goal3. Emissions Capd. Are other policies accounted for incap setting?4. Emissions Coveragef. Compliance obligations (e.g., interimretirement)Allocation of Allowances5. Allocation8

Important forEnvironmentalIntegrity?Important for PolicyImplementation?Already Aligned?Ready to Link?MaybeMaybeYesYesb. Purchase limitNoMaybeYesYesc. Auction formatNoNoYesYesd. Frequency and timingNoNoTBDTBDe. Common auction MaybeTBDTBDa. Qualitative limitsMaybeYesNoNob. Quantitative limitsMaybeYesNoNoc. Certification protocolsMaybeYesTBDTBDd. Invalidation rulesMaybeYesYesYesNoYesTBDTBDa. Price floor and rate of changeYesYesYesYesb. Emissions containment reserveYesYesMaybeMaybec. Cost containment reserveYesYesMaybeMaybed. Price ceiling and rate of changeYesYesMaybeMaybee. Use of unsold allowancesYesNoNoNoa. Penalties for noncomplianceYesYesNoNob. Market oversightYesYesYesYesc. Provisions for delinkingMaybeMaybeTBDTBDd. Process for regulatory updatesMaybeYesTBDTBDDesign Element6. Auction Coordinationa. Third-party participationCost Management7. Temporal Considerationsa. Banking provisionsb. Quantitative restrictions (e.g.,holding limit)c. Qualitative restrictions (e.g., valueacross periods)8. Carbon Offsetse. Liability rules9. Price CollarsEnforcement and Contingencies10. Legal Provisions9

a. Noncompliance PenaltiesCertainty regarding noncomplianceoutcomes and strict enforcement isa key advantage of carbon pricingprograms over more traditional formsof regulation, which often rely on legalproceedings and regulatory negotiations.In fact, many carbon pricing programsenjoy perfect compliance rates, althoughthere are notable exceptions including,for example, regional carbon pricingprograms in China.26 In the context offormal linkage, noncompliance penaltiesdo not have to be replicated word forword, but there needs to be mutual trustbetween programs that enforcement isequally consistent, certain, and strict.California’s program requires aregulated entity to surrender a quantityof allowances that is four times thatentity’s excess emissions—calculated asthe difference between the complianceobligation and any surrenderedallowances or offsets by the deadline—due within five days of the auctionfollowing that deadline. Given the timingof compliance deadlines and quarterlyauctions, this gives regulated entitiesabout one month, at most, to rectify theirnoncompliance. If the excess emissionsare not rectified under this timeframe,then additional violations and finesbegin accruing. The regulation specifiesthat at least three-fourths of an entity’scompliance shortfall must be satisfiedusing allowances from California orallowances from a linked partner.27Washington’s program imposes a similarrequirement that a regulated entity mustsurrender a quantity of allowances that isfour times that entity’s excess emissions.10The legislation gives regulated entitiessix months to rectify its noncompliance.If a regulated entity fails to do so, thenEcology must issue an order (involvinga plan and schedule for coming intocompliance), a penalty of up to 10,000USD per day, or both. In addition,Ecology may impose additional financialpenalties. During the first complianceperiod (lasting from 2023 through 2026),Ecology “may reduce the amount ofpenalty by adjusting the monetaryamount or the number of [excessemissions].28The difference in designs betweenCalifornia and Washington’s approach toenforcement may be significant enoughto threaten a formal linkage. Specifically,Washington gives regulated entities moretime and more “outs”, while grantingEcology substantial discretion to lowerthe strength of enforcement in the earlyyears of the program. Strengtheningthese provisions would help to preservecap integrity.To that end, we make the followingrecommendations to bolster the strengthof enforcement as Ecology draftsregulations: In the event of failure to rectifynoncompliance after six months,Ecology should commit to issuingboth an order and a fine to theoffending regulated entity by statingthis plainly in regulation. This willbolster the strength of enforcement,thereby improving the overalleffectiveness and environmentalimpact of Washington’s program.During the first compliance period,Ecology should commit to notusing its discretion to lower fines orthe quantity of excess allowancesowed. Use of discretion muddies thewaters for regulators and regulatedentities, in addition to diminishingsmooth program functioning.b. Price CeilingsRegulators often design carbon priceswith maximum values to protectconsumers against overly high costs andto limit overall volatility. The two mostcommon tools that serve this functionare “soft” and “hard” price ceilings. Softprice ceilings provide a limited volumeof additional allowances, referred to asa “reserve”, at a predetermined pricemaximum, while hard price ceilingsprint an unlimited volume of additionalallowances at that predetermined pricemaximum. Economic research suggeststhat a small reserve held in a soft priceceiling is an ideal way to balance costsand emissions.29Historically, carbon prices have typicallybeen relatively low and therefore havenot reached the level of the ceiling.30However, recently, a carbon pricingprogram in the Northeast United States,the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative,triggered its soft price ceiling. In addition,as programs mature and take on a moreprominent role in state’s climate policymixes, we are seeing carbon prices risesubstantially, with California beinga prime example of this new trend.Therefore, the consideration of a priceceiling is particularly timely, as moretriggers will likely occur in the nearfuture.California’s approach to price ceilings

is to have three reserves, each with atrigger price. The first two are “soft”(starting with triggers at 41.40 USD and53.20 USD in 2021) and the last one is“hard,” starting with a trigger at 65.00USD in 2021. Each price increases by 5percent plus inflation as determinedby the Consumer Price Index. The hardprice ceiling introduces the possibilityof increased emissions because anunlimited quantity of new allowanceswould be printed to keep prices at the65.00 USD trigger price. Therefore, CARBis required to use revenues from theprice ceilings to purchase reductionson at least a ton-for-ton basis, therebymaintaining the environmental integrityof the cap.The CCA directs Ecology to establish aprice ceiling with a trigger that increasesgradually. The trigger must be equal to“the level established in jurisdictionswith which [Ecology] has entered intoa linkage agreement”.31 The CCA statesthat Ecology must seed the reservewith no less than 2 percent of the totalquantity of allowances available fromthe overall budget for the correspondingcompliance period. If the allowanceprice containment reserve runs out ofallowances, then Ecology will turn toprinting new allowances while usingthe corresponding revenues to investin abatement on at least a ton-for-tonbasis, an approach clearly adopted fromCalifornia’s design.32It is apparent that Washingtonpositioned its legislation to replicatemany of California’s designs for a priceceiling. In this way, the programs arealready incrementally aligning theirdesign, regardless of whether theyeventually formally link. Simply statingthe intent to equate trigger prices witha linked jurisdiction is meaningful. ThatWashington has mimicked California’sapproach in the event of a formal linkshows substantial coordination andsignificant forethought.Regardless of formal linkage, Washingtonshould build upon the positivemomentum from their incrementalalignment with California. One strategyfor doing so would be for Washingtonto align its trigger price with California’slevels when formal linkage occurs, as thecurrent draft rule envisions. This wouldincrease certainty for regulated entities,and it would protect against adversecompetitiveness impacts as well asemissions leakage.A final point concerns the finer detailsof auctions from the price containmentreserve. Comments from Ecology ina recent workshop33 introduce thepossibility of discretionary auctionsfrom the price containment reserve forregulated entities that are behind ontheir compliance efforts. This introducesuncertainty in the market and couldcomplicate linkage efforts. Therefore,this is another area where Washingtonmay look to align with California design.In addition, certain details aroundauction format differ from the designsin California, which could also proveproblematic. For example, the timingand operation of auctions, particularly inthe first year of the market, are uncertainin Washington.Based on the foregoing, we recommendthat: Washington maintain its proposedapproach, which include twoallowance price containmentreserve tiers alongside a hard priceceiling. This approach would alignwith California’s approach to avoidunintended fluctuations in thecarbon price resulting from differingapproaches to price ceilings in thetwo jurisdictions. Washington should not adopt theconcept of discretionary auctionsof allowances from the pricecontainment reserve for regulatedentities that are behind on theircompliance efforts. This not onlyintroduces uncertainty but alsoruns the risk of incentivizing greaterlevels of noncompliance andoverreliance on this measure.c. Cap SettingCap setting is important because it is aprimary determinant of the carbon priceand the program feature that, when welldesigned, ensures emissions decline atthe pace and scale required to achieveclimate targets. In turn, the differencein carbon prices between programs willbe an important consideration if formallinkage negotiations begin in earnest.Because California and Washington maketheir own decisions about cap setting ontheir own timelines, there is a potentialthat formal linkage (or the discussionthereof) could lead both programsto strategically adopt a cap thateconomically benefits their respective11

A ROADMAP Aligning California and Washington’sFOR LINKAGE Carbon Pricesstates. In short, the program that expectsto export allowances may have anincentive to adopt a less stringent capto create surplus allowances and animporter may have an incentive to adopta less stringent cap to reduce spendingon imports.34 35This incentive can be overcome in severalways, any combination of which mayprove effective. Indeed, many arguethat formal linkage leads to enhancedambition by facilitating more aggressivecaps.36 The first way is through endowinga sense of responsibility towardsenhanced ambition.37 In other words,insofar as the intent of the formal linkageis to reduce overall emissions morequickly, then this shared vision caninherently protect against strategicallypermissive caps. Successful coordinationbetween leadership in Washington andCalifornia can play a role in creating sucha shared vision.Another way is to incrementally aligncap setting processes and timing. Forexample, California has a cap formulathat lists each year’s allowance budgetfrom 2021 to 2030. Washington shouldstrive to do the same as it promulgatesits regulations. Separately, Californiaundergoes its periodic Scoping Planprocesses, after which cap levels arepotentially modified. Washingtonhas a program review for its cap-andinvest program that occurs every fouryears and focuses on analyzing itscarbon reductions from economic,environmental, and justice perspectives.It would be beneficial for both statesto include detailed information oncomplementary policies. It may alsobe useful to sync the timing of reviewsacross jurisdictions. This would allowfor the jurisdictions to make cap settingdecisions simultaneously with sharedinformation.A related concern is that if a programis nonbinding (that is, a carbon priceof zero or a carbon price resting on theminimum “floor” price), then exports ofallowances from that program to anotherprogram erodes the environmentalintegrity of the overall cap. In otherwords, in this example, the exportedallowances, unlike allowances from the12local jurisdiction, do not represent anopportunity cost to regulated entitiesof emitting one ton of emissions.38This is not a concern in California atthe moment because the carbon priceis high above its floor and is thereforeclearly binding. Moreover, allowanceprice projections expect that prices willstay well above the floor for into thefuture. Every allowance in the programconsequently represents one ton ofemissions. Modeling conducted byVivid Economics for the Washington’sDepartment of Ecology projects thatprices will be well above the program’sproposed floor price,39 which suggeststhat this is unlikely to be a concern inWashington. However, Washington’scap-and-invest program has not startedand there is therefore no price data for adirect comparison to California.Nonetheless, to further track potentialnonbinding caps, we recommend thatCalifornia and Washington track therole of complementary policies in theirrespective programs because they are akey input to the demand for allowances.The information collected by regulatorsin their respective jurisdictions shouldbe shared with all current and potentialformal linkage partners. Californiacollects and publishes this informationvia its periodic Scoping Plan processes.While Was

emissions that fuel climate change. Carbon prices are usually implemented through a carbon trading or carbon taxation program. Regulators around the world are increasingly deploying carbon pricing to complement their existing policy approaches.1 Currently, more than 65 carbon prices regulate nearly 22 percent of global emissions,