Transcription

EU BANKS’ FUNDING STRUCTURES AND POLICIESm ay 2 0 0 9EN

EU BANKS’ FUNDINGSTRUCTURES AND POLICIESM AY 20 0 9In 2009 all ECBpublicationsfeature a motiftaken from the 200 banknote.

European Central Bank, 2009AddressKaiserstrasse 2960311 Frankfurt am MainGermanyPostal addressPostfach 16 03 1960066 Frankfurt am MainGermanyTelephone 49 69 1344 0Websitehttp://www.ecb.europa.euFax 49 69 1344 6000All rights reserved. Reproduction foreducational and non-commercial purposesis permitted provided that the source isacknowledged.Unless otherwise stated, this document usesdata available as at end of March 2009.ISBN 978-92-899-0448-3 (online)

CONTENTS1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY4LIST OF BOXES:Box 12 PROJECT BACKGROUND73 FUNDING SOURCES AND STRATEGIES83.1 General trends: funding sources3.2 Consequences of the crisis forbanks’ funding strategies3.3 Action by public authorities torestore banks’ access to funding4 BANK DEBT COMPOSITION ANDINVESTORS4.1 Developments in the issuance ofbank debt securities4.2 Debt investors5 COLLATERAL AND ITS MANAGEMENT5.1 Constraints on collateral use5.2 Central banks’ responses oncollateral5.3 Responses in the way banksmanage their collateral6 INTERNAL TRANSFER PRICING6.1 The main parameters of aninternal pricing system6.2 Shortcomings in banks’ internaltransfer pricing policies6.3 Need for rules relative to internaltransfer pricing policy7 THE FUTURE OF FUNDING MARKETS –POTENTIAL ISSUES AND HURDLES AHEAD7.1 Immediate challenges7.2 Restarting funding markets813Box 2Box 3Guaranteed versusnon-guaranteed funding: pricingand implementation detailsBond markets: a key financingtool for banksChanges to the Eurosystemcollateral ES123Costs, limits and time horizonsof government bank debtguarantee schemes, andamounts issuedInternal transfer pricing:theoretical toolsInternal pricing of liquidity –a future challenge for regulatorsand financial stability353841ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 20093

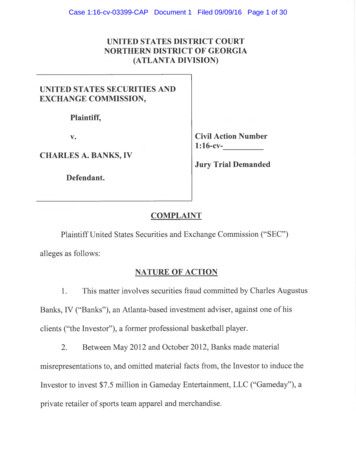

1EXECUTIVE SUMMARYPROJECT BACKGROUND AND APPROACHIn the light of recent developments on financialmarkets, the Banking Supervision Committee(BSC), decided to carry out an in-depthassessment of the impact the crisis is having onbank funding. This assessment, which coveredthe sources and cost of funding, as well as theway in which banks have managed their fundingstructures, was based on both market data anddata published by banks. The report is based onthe information available until end ofMarch 2009. The analysis also benefited from asurvey of 36 mostly medium-sized and large EUbanks.1FUNDING SOURCES AND STRATEGIESHAVE ALTEREDAs the crisis has unfolded, liquidity has becomea scarce good and all funding sources havegradually been affected. Deposits have beenaffected to a lesser extent and central bankmoney has remained available throughout theturmoil, as central banks stepped up their effortsto support funding needs at an early stage in thecrisis.One immediate reaction on the part of banks thatpreviously relied mainly on wholesale fundinghas been to change their funding to more stablesources. Surveyed banks confirm that depositshave become the preferred source of funding,albeit in increasingly competitive marketconditions. Banks are also seeking to strengthentheir deposit base by investing more in customerrelations. The increased interest on deposits isreducing the potential market share of banksthat were already reliant on retail deposits.Given the extent of funding restrictions,coordinated action across central banks andgovernments has become necessary in order toalleviate the funding gap. Central bank action hasfocused on short-term funding, with maturitiesranging from overnight to six months –and as long as one year in the case of the Bankof England. At the same time, governmentpackages have mostly targeted longer-term4ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 2009funding through guarantee schemes. However,these temporary measures have not yet managedto unlock longer-term liquidity. In fact, part ofthe liquidity that has been injected has found itsway into central banks’ deposit facilities in theform of precautionary hoarding of liquidity, or issimply being recycled in the overnight market.Given the long-term funding constraints, banks’focus has shifted to short-term funding. In fact,the banks surveyed are more concerned aboutday-to-day market developments and the impacton their funding structures. This has made banksextremely sensitive to market developments. Onan aggregate basis, this behaviour can representa serious obstacle to the normalisation offunding, since it inhibits a long-term approachto funding. In fact, the banks surveyed wererelatively pessimistic about the recovery ofmarket funding and noted that it would probablytake years for market funding to normalise.Several of the banks surveyed conceded thatgovernment and central bank measures were keyin helping to avoid a full-blown collapse of thebanking system. However, certain banks statedthat government measures had altered the levelplaying field between healthy and less healthybanks, and that 2009 would probably see banks’normal issuance activities being crowded outby government-guaranteed issuance. This crisisis, in some respects, also giving rise to a homecountry bias. Since banks are more familiar withdomestic markets, renewed funding structuresseem to be pointing towards building a strongdomestic investor base.FUNDAMENTAL CHANGES IN MARKETSFOR BANK DEBTThe issuance of their own debt securities is anintegral part of many larger banks’ fundingstrategies. However, during the current financial1The 36 surveyed banks were interviewed in the period betweenNovember 2008 and early January 2009. Of the 36 bankssurveyed, 28 were single banks or parent banks of a bankinggroup, and 32 had their headquarters in the euro area. The bankssurveyed were mostly involved in retail banking, mortgagebanking, corporate finance activities and asset management. Thissample does not claim to be representative in either statisticalterms or for the EU banking market.

crisis, confidence in banks as debtors haseroded, risk aversion has increased and investorssuch as money market and mutual funds havehad to deal with their own liquidity difficulties(e.g. redemptions). Banks’ debt issuanceactivities have been negatively affected, withboth net issuance and debt instrument maturitiesdecreasing. In parallel, investor demand for moreshort-term instruments such as certificates ofdeposit has increased. And while covered bondsinitially appeared to be a viable replacement foroff-balance sheet securitisation, their issuancehas also dried up in a number of countries.Following the implementation of governmentrescue plans, unsecured bonds and coveredbonds now have to compete with governmentguaranteed instruments. How guaranteed andnon-guaranteed instruments coexist withinthe bond market in terms of relative pricing,quantities and investor base will be a key factorin determining whether or not funding marketseventually reopen.RENEWED IMPORTANCE OF COLLATERALConditions in the repo market have tightened andbecome so constrained that the range of assetsaccepted as collateral has narrowed further, withgovernment bonds more or less being the only typeof collateral accepted. These constraints weretranslated into a generalised increase in haircuts 2,regardless of the seniority, maturity, rating orliquidity of the collateral. Banks surveyed for thisreport confirmed that these difficulties reinforcedtheir perception that collateral management was akey element of their management of liquidity andfunding. These difficulties have also given banks agreater incentive to accelerate investment in re. Some banks have increased the sizeof their strategic reserves of eligible assets in orderto secure central bank contingency funding. Someof them have also increased the centralisation oftheir collateral management in order to optimisecollateral and liquidity flows between differententities on a cross-border basis.In this context, banks have also shown increasedinterest in central bank actions with regardto collateral (i.e. the loosening of eligibilityI EXECUTIVESUMMARYcriteria and the recognition of new types ofasset as eligible collateral). The extension ofeligibility criteria allowed credit institutionsto both reserve their highest quality assets forrepo transactions in wholesale markets andmaximise the use of collateral in central bankcredit operations. In addition, some banks havebeen securitising part of their loan portfolios forthe sole purpose of using the senior tranches asEurosystem collateral. This has led to concernthat central banks could end up being the mainholders of securitised instruments, given thefreeze in the securitisation markets and thefact that asset-backed securities account for asignificant proportion of the collateral used bycounterparties in Eurosystem credit operations.FLAWS IN INTERNAL PRICING POLICIESThe tightening liquidity conditions havehighlighted the flaws that developed in someinternal pricing practices during the period oflow interest rates and low liquidity premia. Iffunding costs are priced too cheaply internally,business units have an incentive to take risksby increasing their leverage and maximisingvolumes, as they are not being chargedappropriately for the associated liquidity risk.The shortcomings of internal liquidity policiesincluded overly optimistic assumptions aboutthe unwinding of trades, cross-subsidisationof activities and the provision of inaccuratelypriced backstop credit lines. Moreover, liquidityrisk was sometimes intentionally underestimatedinternally, in order to gain market share in thecontext of strong competition.According to the banks surveyed, more attentionis now being paid to internal pricing policies.Most banks have increased the cost of internalliquidity supplies, using broader criteria whichnow include the type of funding, the location ofthe subsidiaries, the nature of the business linesand the type of internal counterpart. Interestingly,some banks have allocated decision-making inthis area to more senior management.2Sometimes up to 100%, preventing the asset from being used ascollateral.ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 20095

negatively on the probability of retail andcorporate customers defaulting. Suchdeterioration in the credit quality of banks’customer base could then feed back tobanks’ balance sheets, further constrainingtheir ability to fund themselves.HURDLES IN RESTARTING MARKETS FOR BANKFUNDINGThe BSC foresees a number of hurdles inrestarting markets for bank funding. 6Government-guaranteed funding wasintended to help rekindle the issuanceof bank debt. The successful issuance ofguaranteed bonds shows that this measurehas been effective to some extent, especiallyas some banks have also been able to issuenon-guaranteed bonds. Guaranteed debtappears to have been purchased by thetype of investor which generally takes onexposure to government risk rather thancorporate credit risk. This investor basetends to invest for longer periods of timeand in a more stable manner than traditionalinvestors in bank debt. The lack of overlapwith the usual investors in bank debt iscurrently preventing guaranteed issuancefrom crowding out non-guaranteedissuance. However, in the long term, thetraditional (credit risk) investor base willneed to be encouraged to begin investing inbank debt again. There is currently no signof this happening. In addition, there is somerisk of government debt itself crowding outprivate debt.Few respondents presented views on when,or how, markets might begin functioningagain. They emphasised the need formarkets to be reassured regarding thehealth of the asset side of bank balancesheets before investor confidence couldreturn. As regards the reopening ofsecuritisation and covered bond marketsmore specifically, while it is essential thatsimple and transparent secured structuresbe established, it is also of vital importanceto investors that liquidity be restored tothese markets.The deleveraging process and the drying-upof funding markets may well also constrainbanks’ balance sheet growth and therebyrestrict their ability to provide credit tothe economy. This, in turn, could impactECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 2009CHALLENGES FOR BANKSThe BSC has identified two immediatechallenges as regards the funding of EU banks. First, increasing the share of retail depositsin order to strengthen a bank’s overallfunding structure is desirable, but shouldnot be viewed as a panacea preventingbank runs, as retail deposits are generallyheld at sight and do not, therefore, protectbanks from a sudden outflow of funds.The credibility of the deposit guaranteescheme is essential in avoiding depositruns. Maturity risk can be mitigatedby lengthening the maturity of fundingwherever possible, regardless of the type offunding. Ultimately, however, the only realantidote to a bank run is to ensure that thequality of the asset side of the balance sheetis sufficient to ensure continued investorconfidence. Trust in the relevant bank’sgovernance and risk management are alsoessential. Second, the BSC is of the opinion that itis important for banks to define their ownexit strategies with a view to reducingtheir reliance on government support.One possibility would be to improve theirknowledge and monitoring of their investorbase for primary debt issuance. This wouldenable them to develop better relationshipswith large counterparties, whose decisionson whether or not to continue funding thebank can be key in determining the bank’sfunding position, or even very existence. Inaddition, knowing investors better wouldenable banks to better predict what stressesthese counterparties might come under, inturn allowing banks to better manage theirforward-looking liquidity positions. Thecurrent crisis has also shown that it could

be useful for banks to be aware of thegeographical spread of their investor base.As a matter of fact, it appears favourableto have a certain degree of diversity in thecomposition of debt investors to cater fortimes of stress. Domestic investors appearto have been less “flighty” than investorsfrom abroad, perhaps partly because theyare more aware of the particular features oftheir local banks.CONCLUSIONSIn concluding its analysis, the BSC is of theview that banks’ restricted lending activitieshave led to some reshaping of the bankingindustry, with particular pressure being placedon certain business models (i.e. funding modelsbased almost exclusively on wholesale sourcesand business structures focused on retailsecured lending or specialist lending activities).Banks are becoming more domesticallyoriented in their activities, partly in responseto the prevailing counterparty risks, but also onaccount of the somewhat national orientationof government support. Banks are also seekingsimplicity in their structures.2PROJECT BACKGROUNDIn the past few years, banks have strived to reducewhat they perceived to be excessive dependenceon deposit-based funding by having recourseto market-based funding. The development ofasset securitisation played an important role infostering this shift, as it facilitated the expansionof the funding tools available to banks. Thecurrent crisis has challenged this developmentand highlighted the following issues: Decreasing availability of funding as aresult of the freezing of wholesale andinterbank markets. Rising cost of bank funding, partly as aresult of increased bank counterparty risk. Shortening of funding maturities challengesasset liability management (ALM) and2 PROJECTBACKGROUNDprofitability in the context of relativelyflat or even inverted yield curves in theeuro area. This results from contingencyfunding plans that did not fully cover therisks of maturity mismatches on and off thebalance sheet. Currency mismatches in funding haveoccurred as funding sources in foreigncurrencies have become severely restricted.In the light of these issues, the BSC decided tocarry out an in-depth assessment of the impactthat the crisis is having on bank funding.The assessment was based on both market dataand data published by banks. The report is basedon the information available until end ofMarch 2009. The analysis also benefited from asurvey of 36 mostly medium-sized and large EUbanks, 28 of which were single banks or parentbanks of a banking group, and 32 of which hadtheir headquarters in the euro area.3 The surveywas carried out by means of a questionnairefocusing on the main aspects of bank funding.The answers received reflect the opinions andpolicies of this sample of banks. The BSC doesnot claim that the sample is representative of theEU banking market in statistical terms.The report is structured as follows: Section 3covers the changes in banks’ funding sourcesand strategies, as well as the scope of publicauthorities’ actions to restore access to funding;Section 4 covers developments in bank debt,including debt investors’ behaviour andcomposition; Section 5 discusses collateraland its management, dealing with both internaldevelopments within banks and developmentsor influences resulting from changes in centralbanks’ collateral frameworks; Section 6discusses the role played by the internal pricingof liquidity within banks and its impact onincentives; and Section 7 looks at the immediatechallenges for banks’ funding, the governmentmeasures aiming at restarting funding markets,3Participating countries involved in the project have been:Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, theNetherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom.ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 20097

and banks’ views on how and when marketsmight restart.The report also includes three annexes, whichprovide additional information on governmentguarantee schemes, as well as on the pricing ofinternal transfers and the importance of such pricingas underlined in recent supervisory initiatives.3FUNDING SOURCES AND STRATEGIESThe funding strategies of banks have changedsubstantially owing to the financial market crisis.The economic environment prior to the crisisfavoured funding structures that were highlydependent on ample liquidity. When that ampleliquidity unexpectedly ceased to be available,banks that relied heavily on market fundingwere forced to make significant adjustments,not only to their funding strategies, but also, insome cases, to their business models.Conceptually, commercial banks fund theirbalance sheets in layers, starting with a capitalbase comprising equity, subordinated debt andhybrids of the two, plus medium and long-termsenior debt. The next layer consists of customerdeposits, which are assumed to be stable inmost circumstances, even though they canbe requested with little or no notice. The finalfunding layer comprises various shorter-termliabilities, such as commercial paper, certificatesof deposit, short-term bonds, repurchaseagreements, swapped foreign exchangeliabilities and wholesale deposits. This layer ismanaged on a dynamic basis, as its compositionand maturity can change rapidly with cash flowneeds and market conditions. This fundingstructure is usually relatively stable, and changesin the structure are fairly sluggish.The following sections focus on the changesthat have taken place in these funding layerssince the crisis began, highlighting the fundingconditions and sources beforehand and themain policy measures taken in order to mitigatefunding restrictions in markets.8ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 20093.1GENERAL TRENDS: FUNDING SOURCESBEFORE THE CRISIS: ABUNDANT SOURCES OFFUNDING FUELLED BANK LEVERAGEBefore the crisis, the global economy wascharacterised by strong economic growth, lowinterest rates and risk premia, and abundantliquidity. At the same time, banks’ leverage wasexpanding rapidly. The growth of loan stockswas partly offset by the growth of deposits.However, despite the fact that deposits wereincreasing, the magnitude of lending surpassedthat of deposits in several banks (see Chart 1).As banks’ stocks of deposits were not sufficientto provide an adequate base for their growingbusiness, banks resorted to other available sourcesfor funding, such as securitisation (through the“originate to distribute” model), covered bondsand interbank markets. Given the availability ofample liquidity, it was not difficult for banks toraise funds from the markets. This is clearlyvisible from the expansion of banks’ balancesheets. For example, between December 2003and December 2007 the total balance sheet ofeuro area MFIs increased by 53%, rising from 14.6 trillion to 22.3 trillion.44Source: Consolidated balance sheet statistics for euro area MFIs(available on the ECB’s website).Chart 1 Ratio of loans to deposits in largeEU banks (corrected for extreme .01.51.51.01.00.50.50.0H12000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 20080.0Source: Bankscope.Note: Box plot diagram indicating minimum value, interquartilerange, median and maximum value.

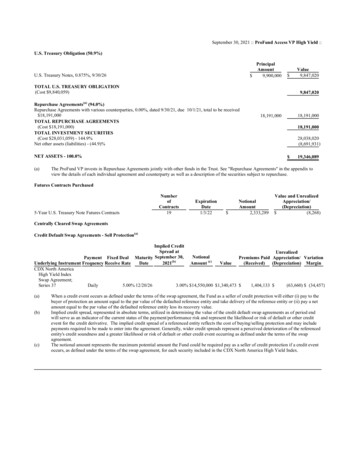

(i) Maturity mismatchesA change in the funding trends of Europeanbanks seems to have occurred in 2003, withlong-term funding beginning to slightly decreaseand short-term funding starting to increase(see Chart 2). In 2003, deposits accounted, onaverage, for around 42.4% of total liabilities,with capital market funding accounting for 27%.The corresponding percentages were 39.3% and3 FUNDINGSOURCES ANDSTRATEGIES26.6% respectively in 2007. At the same time,from 2003 onwards covered bonds were alsoused in many European countries as an additionalsource of funding. Covered bonds outstanding inEurope increased by 22.7% between 2003 and2007, rising from 1,686 billion to 2,069 billion(see Chart 3). The expansion of covered bondmarkets was considerable, with the number ofissuing countries increasing.PATTERNS IN FUNDING SOURCES PRIOR TO THE CRISISChart 2 European banks’ liabilities, includingnet interbank liabilities (overall structure)Chart 3 Covered bonds outstanding inEurope (long term)(percentages)(EUR billions)depositsinterbank liabilitiesmoney market 02003200420052006ESSEUKDEDKFRcapital market fundingother ource: Bankscope.Source: European Covered Bond Council.Chart 4 Interbank loan (short term)Chart 5 Growth of securitisation in Europe(long term)(EUR billions (left-hand scale); percentages (right-hand scale))(EUR billions)EUeuro areagrowth rate in the EU (secondary axis)growth rate in the euro area (secondary 200320042005200620072008Source: ECB.Note: UK data do not include interbank loans outside the euroarea and the United Kingdom.0200320042005200620072008Source: European Securitisation Forum (see: http://www.europeansecuritisation.com/Market Standard/ESF DataReport Q4 2008.pdf).ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 20099

Between 2003 and 2007 money market fundingproviding short-term liquidity (e.g. certificates ofdeposits, commercial paper and short-term bonds)increased as a percentage of total liabilities inEuropean banks’ balance sheets. In 2003 moneymarket funding accounted for 11.8% of totalliabilities, while at the end of 2007 it accountedfor 16%. In particular, interbank markets becamea more prominent source of short-term fundingfor banks. In net terms, 0.1% of EU banks’ totalliabilities were derived from interbank marketsin 2003, and 2.9% came from this source in2007. The annual growth rate of interbank loansreached 14% in the EU in 2006, and 16% in theeuro area in 2007 prior to the crisis (see Chart 4).In addition, securitisation increased considerably(see Chart 5). By the end of 2007 annual issuancevolumes had grown by 129% in comparisonwith 2003, reaching 497 billion. In 2007, thetwo most popular types of securitised assetswere residential mortgage-backed securitiesand collateralised debt obligations (CDOs),which accounted for 52% and 27% respectivelyof total securitised assets.5 Significant usewas also made of commercial mortgagebacked securities (CMBSs). The use of othercollateral underlying securitised assets declinedconsiderably, falling to 11% of total securitisedassets in 2007.A general look at banks’ funding structureshighlights the existence of national andinstitutional differences. Such variation canbe explained by the level of sophistication offinancial markets and banks’ business models.10 For instance, countries with less maturefinancial markets tend to be more reliant ondeposits for their funding. In some cases,deposits account for up to 85% of banks’total liabilities. In more open financialmarkets, deposits constitute around30-50% 6 of banks’ total liabilities. Banks’ core activities also affect thefunding structure. The relative shares ofdeposits and market funding may varyconsiderably depending on the focus of theECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 2009banks’ activities (i.e. retail, market-relatedor universal).It is also noteworthy that banks’ off-balancesheet items increased rapidly in the years priorto the crisis. In fact, many banks had financialvehicles that were not included in their balancesheets, but which made investment decisionsfor which their parent companies were liable.Off-balance sheet vehicles offered both shortterm (through asset-backed commercial paper)and long-term (through securitisation) sourcesof funding.All in all, the growing imbalance betweenthe longer-term lending to customers and theshorter-term funding of banks’ activities createda maturity mismatch in banks’ balance sheetsand exposed banks to increased funding andcounterparty risks.(ii) Currency mismatchesIn the same way, banks’ funding patterns alsohelped to create a dangerous currency mismatch.Traditionally, there are two main modelsfor cross-currency liquidity management inbanking. Some banks control the maturity profile oftheir assets and liabilities irrespective oftheir currency and make up for shortagesin a given currency through short-termforeign exchange swaps. Others manage their liquidity risk exposureseparately for each individual currency.Between 2000 and mid-2007 European banks’net long US dollar positions grew to aroundUSD 800 billion, being funded in euro. Thiscreated significant exchange rate risk andconsiderable dependence on the foreignexchange swap market, which penalised bankswhich had adopted the first approach.56“Securitised issuance in Europe by type of collateral” (2007);Sources: Thomson Financial, JP Morgan, Merrill Lynch,Bloomberg.Source: ECB.

THE IMPACT OF THE CRISIS: SCARCERAND COSTLIER SOURCES OF FUNDINGThe financial turmoil that started insummer 2007, triggered by the mortgageproblem in the United States, strained banks’funding sources and had a considerable impacton banks that relied heavily on wholesale funding(e.g. Northern Rock). The declining confidencethat resulted from the rapid deterioration ofratings, valuation losses for securitised assets andthe appearance of off-balance sheet commitmentsin banks’ balance sheets heightened counterpartyrisks and made banks and other investorsmore cautious about lending to one another.As confidence deteriorated, a severe dislocationtook place in the global funding network,gradually affecting all funding markets. The firstmarket affected was the interbank market. Banksbegan to hoard liquidity for precautionary reasonsand to overcome fire sales. By then, a majorliquidity breakdown had taken place. Marketliquidity for mortgage-related securities andstructured credit products rapidly disappeared.Government bond yields plunged as investorsrejected risky assets and turned to the relativesafety of government securities. The collapse ofLehman Brothers in September 2008 exacerbated3 FUNDINGSOURCES ANDSTRATEGIESthe loss of confidence. The shock spread rapidlyfrom the interbank market to all other markets,such as the CDS market for financials andnon-financials, the commercial paper market,markets for covered bonds and bank bonds,and other long-term funding markets. Centralbanks provided liquidity injections to supportshort-term funding needs (see Chart 6).Another consequence of the financial crisishas been increasing funding costs as the costof market-based bank financing via bonds andequities remains at historically high levels(see Chart 6). Most major CDS indices haveexceeded their March 2008 peaks, recedingonly on speculation that the most severelyaffected banks would receive some kind ofgovernment assistance. However, following theimplementation of rescue plans (see Table 1 andSection 3.3), some uncertainty still remains.Government support has allowed banks’ CDSpremia to be reduced. However, because ofbanks’ changing fundamentals related to assetwrite-downs, counterparty risk and the impactof the general economic downturn, trends inCDS spreads have become more uncertain.A breakdown of credit and non-credit riskChart 6 Funding sources during the crisisPre-crisisAugust 2007to summer 2008LehmanBrothers’ FailureAfter governmentrescue palns2009 outlookShort-term financingInterbankCertificates of depositsDepositsCentral bankLong-term financingNon-guaranteed bondsGuaranteed bondsCovered bondsSecuritisationNote: This figure tries, by way of a “traffic light” analogy, to illustrate, at the various stages of the crisis, the availability of fundingsources for the European banking system. It distinguishes between three states: Green: available; Orange: signs of difficulties in gaining access; Red: impaired; White: not relevant.Please note that this is intended to reflect the overall situation in Europe and may not reflect specific national situations.ECBEU banks’ funding structures and policiesMay 200911

Chart 7 Cost of fundin

integral part of many larger banks' funding strategies. However, during the current fi nancial 1 The 36 surveyed banks were interviewed in the period between November 2008 and early January 2009. Of the 36 banks surveyed, 28 were single banks or parent banks of a banking group, and 32 had their headquarters in the euro area. The banks