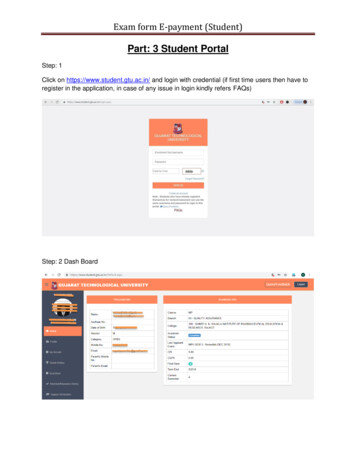

Transcription

THE POWER OF PURPOSEFUL AGINGPURPOSE

SUMMIT PARTICIPANTS THEPOWER OFPURPOSEFULAGINGCulture Change and the New DemographyCONTENTSPrefaceBReport from the 2016 Purposeful Aging Summit31 When Purpose and Aging Merge102 The Case for Purposeful Aging203 Challenges on the Path324 Communicate, Convince, Connect46Conclusion58Endnotes59Board of Advisors621

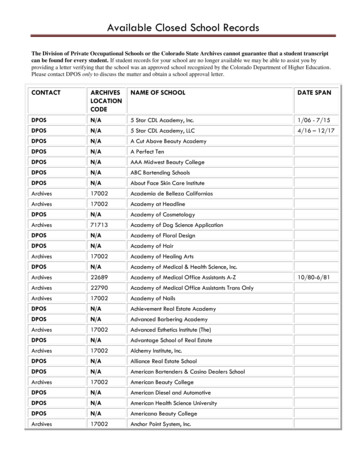

Left to right:Karabi AcharyaDirector, Robert WoodJohnson FoundationArthur BilgerFounder and CEO,WorkingNationPatricia BoyleNeuropsychologist, RushAlzheimer’s DiseaseCenter, Rush UniversityMedical CenterLaura CarstensenProfessor of Psychologyand Fairleigh S. DickinsonJr. Professor in PublicPolicy, Stanford University;Director, Stanford Centeron LongevityHenry CisnerosChairman, ExecutiveCommittee, SiebertCisneros Shank & Co.,LLC; Chairman, CityView;Former Secretary, U.S.Department of Housingand Urban DevelopmentPinchas CohenDean, Leonard DavisSchool of Gerontology,and Executive Director,Ethel Percy AndrusGerontology Center,and William and SylviaKugel Dean’s Chair inGerontology, Universityof Southern CaliforniaCatherine CollinsonPresident, TransamericaInstitute; ExecutiveDirector, Aegon Center forLongevity and RetirementJoseph CoughlinFounder and Director,Massachusetts Instituteof Technology AgeLabJohn FeatherCEO, Grantmakersin AgingSusan GianinnoChairman, North America,Publicis WorldwideMarc FreedmanFounder and CEO,Encore.orgLynn GoldmanMichael and Lori MilkenDean, Milken InstituteSchool of Public Health,George WashingtonUniversityKen DychtwaldPresident and CEO,Age WaveLinda FriedDean and DeLamarProfessor of PublicHealth, ColumbiaUniversity MailmanSchool of Public Health;Professor of Medicine,Columbia College ofPhysicians and Surgeons,and Senior Vice President,Columbia UniversityMedical CenterRichard EisenbergManaging Editor,Nextavenue.org, PBSLaura GellerSenior Rabbi, TempleEmanuel of Beverly HillsWilliam DamonProfessor, StanfordUniversity; Director,Stanford Center onAdolescenceJohn GompertsPresident and CEO,America’s PromiseAllianceBarbara BradleyHagertyAuthor; JournalistKerry HannonAuthor and Columnist;Expert in CareerTransitions andRetirementMichael HodinCEO, Global Coalition onAging; Managing Partner,High Lantern GroupJody HoltzmanSenior Vice President,Market Innovation, AARPCarol HymowitzEditor-at-Large,Bloomberg NewsPaul IrvingChairman, MilkenInstitute Center for theFuture of AgingIna JaffeCorrespondent, NPRPaula KergerPresident and CEO, PBSSherry LansingCEO, Sherry LansingFoundation; Founder,EnCorps TeachersProgramBecca LevyProfessor ofEpidemiology, YaleSchool of Public Health;Professor of Psychology,Yale UniversityDavid LindeCEO, Participant MediaDonald MillerLeonard K. FirestoneProfessor of Religion andCo-Founder, Center forReligion and Civic Culture,University of SouthernCaliforniaPhilip PizzoFounding Director,Stanford DistinguishedCareers Institute; Davidand Susan HeckermanProfessor of Pediatricsand of Microbiology andImmunology and FormerDean, Stanford UniversitySchool of MedicineAi-jen PooDirector, NationalDomestic WorkersAlliance; Co-Director,Caring AcrossGenerationsKimon SargeantVice President,Human Sciences, JohnTempleton FoundationTrent StampCEO, Eisner FoundationFernando Torres-GilProfessor of SocialWelfare and Public Policyand Director, Center forPolicy Research on Aging,University of California,Los AngelesLester StrongVice President,Experience Corps andExternal Affairs, AARPFoundationJohn WhyteDirector, ProfessionalAffairs and StakeholderEngagement, U.S. Foodand Drug AdministrationLara SullivanVice President, Strategyand Portfolio Solutions,Worldwide Research andDevelopment, Pfizer Inc.John ZweigChairman, HealthCare and SpecialistCommunications,WPP GroupWendy SpencerCEO, Corporationfor National andCommunity ServiceNora SuperChief, Programs andServices, NationalAssociation of AreaAgencies on AgingD

About the Milken InstituteThe Milken Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank determinedto increase global prosperity by advancing collaborative solutions thatwiden access to capital, create jobs, and improve health. We do thisthrough independent, data-driven research, action-oriented meetings,and meaningful policy initiatives.About the Center for the Future of AgingThe mission of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging is toimprove lives and strengthen societies by promoting healthy, productiveand purposeful aging. @MIAging @MilkenCFAaging.milkeninstitute.org Future of AgingCFA@milkeninstitute.orgAcknowledgmentsOur work to advance the cause of purposeful aging could not progress withoutthe dedicated efforts of colleagues who share our aspirations. Many peoplehave played a part in the success of the Purposeful Aging Summit and of thisreport, which captures the spirit and insights of the event. I want to acknowledge several of them for their valuable contributions.My gratitude to Arielle Burstein for her help in organizing the Summit andpreparing the materials that informed our conversations. I am grateful as wellto Rita Beamish for her words and efforts as my principal writing collaborator,to Edward Silver for his critical eye and editorial prowess, and to Jane Lee forher creative and thoughtful design work. My appreciation to Bryan Quinan andNancy McHose for their help planning the event, and to my assistant, ShantikaMaharaj, for her dependable support. Liana Soll, Sophie Okolo, and SindhuKubendran also deserve recognition for their valued efforts at the Center for theFuture of Aging.My special thanks to our Purposeful Aging Summit participants and to themembers of our Board of Advisors. We’re honored to work with this exceptionalgroup of leaders. Finally, let me express my deep appreciation to the JohnTempleton Foundation for its support. The Foundation’s dedication to researchand activities that elevate purposeful living inspires our daily work.Paul IrvingChairmanMilken Institute Center for the Future of AgingSanta Monica, Calif.PREFACEWith people living longer than ever and the world’solder population expanding at an unprecedented rate,the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging convenedthe Purposeful Aging Summit in Los Angeles in 2016.Thought leaders from public policy, business, academia,philanthropy, and media gathered to discuss reframingperceptions of aging in the 21st century. The participantsacknowledged the importance of overcoming deeplyingrained bias, and the need to shed light on the compellingbut little-understood benefits of purposeful aging. Theyrecognized the upside of changing the culture of agingfor individuals old and young. This report summarizes thethemes, findings, and vision of the Purposeful Aging Summit. 2016 Milken InstituteThis work is made available under the terms of the Creative CommonsAttribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, available atcreativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/3

As a society, we tend to believe thateach generation is an insular one,and that the interests of each areunique and separate from those ofothers. But now more than ever,people young and old must join forcesto address problems that affectboth of their communities.MICHAEL EISNER45

PURPOSE IN ACTIONCountless older Americans are making a differencein their communities and the world by embracingtheir later years with creativity, purpose, and passion.They are volunteers for social causes and civicorganizations. They are engaged in encore careers.They are mentors for young people and caregiversfor one another. Throughout this report, we highlightordinary people whose commitment demonstratesthe vitality and productivity of older lives.6PURPOSE IN ACTIONDIANE RALEIGHCo-Founder, Olmoti ClinicAs a former Peace Corps volunteer, Diane Raleigh never forgot about thegreat need she saw among Africa’s marginalized populations. At the age of70, still enjoying her career as a clinical psychologist in Palo Alto, Calif., shedecided to do something about it. Raleigh co-founded the Olmoti Clinic inremote northern Tanzania, aiding an impoverished Maasai community. Shealso serves as executive director of its operating trust, singlehandedly raisingmoney for the clinic. Proving that one person can change lives, Raleigh hastransformed the community by building a pipeline to provide fresh waterand constructing a primary school for children who can’t make the long,dangerous trek to the nearest village school. OlmotiClinic.org7

2BILLION900MILLIONAS THE WORLD TURNS, IT AGESWorld population age 60 and over is projected toincrease from 900 million in 2015 to 2 billion by 2050.Those age 80 and older will quadruple. In theUnited States, the 65-plus cohort will nearlydouble to 83.7 million from 43.1 million.PURPOSE IN ACTIONHENRY ROCKFounder and Executive Director, City Startup LabsHenry Rock had an epiphany at age 60: He wanted to foster a “reimagining”of black male millennials in the eyes of society and the young men themselves. Summoning his experience as a media executive and insights hegained from successful entrepreneurs, he launched City Startup Labs in 2014with financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation. The Charlotte, N.C.,organization instructs African Americans between 18 and 34 on launchingtheir own businesses. Now in its third year and newly housed at theUniversity of North Carolina, CSL focuses on character and critical thinkingas well as entrepreneurial how-tos, culminating in student pitches in frontof potential investors and local businesspeople. citystartuplabs.comSources: World Health Organization, U.S. Census Bureau.89

CHAPTER 1WHENPURPOSEAND AGINGMERGEThe world is crossing ademographic frontier. While itis foreign to us in many ways,the landscape on the otherside holds great possibilities.Every day in the United States, 10,000 people marktheir 65th birthdays. One in five Americans will havepassed this milestone in 2030, and the global population aged 60 and over is projected to total morethan 2 billion by midcentury, up from 900 million in2015.1 While this profound shift has stirred widespreadconcerns, it brings boundless opportunities to changemillions—perhaps billions—of lives for the better. Andthey are only beginning to be recognized.The evidence from numerous studies tells us thatthe record number of older adults is a unique humancapital resource. Its sheer size demands that weexplore its vast potential and employ it for the betterment of our world. At the same time, many agingadults fear that their “golden years” won’t be goldenat all. Concerns about health, safety, and financialsecurity loom large for people in their 60s and beyond.Furthermore, while advances in public health, science,and economic development have given us the gift oflongevity, age prejudice remains, so ingrained that itflourishes underrecognized and unacknowledged deepin our collective psyche. In today’s culture, adding moreyears to our lives does not necessarily mean addingmore life to our years.Purpose and PotentialThe new longevity landscape does hold powerfulprospects, however, if we open doors to this humanresource. A growing body of research suggests thataging with purpose offers solutions not just to problemsinherent in aging itself, but to an array of other challenges that demand attention. Older adults can infusesocieties with transformative social and economicbenefits. Through their insight and ability to mentor,they help the young learn and develop. As caregiversand volunteers, they help one another age with dignityand provide invaluable support. In work settings, theybring perspective, experience, and emotional stability.Let’s celebrate the fact that the aging population is, inthe words of Encore.org CEO Marc Freedman, “ouronly increasing natural resource.”The underpinning of these assertions is not soft scienceor speculation. It is well documented, although not wellrecognized, that older adults offer unique contributionsand that they gain mentally and physically throughThe afternoon of life is just as full ofmeaning as the morning; only, itsmeaning and purpose are different.CARL JUNG10CHAPTER 1: WHEN PURPOSE AND AGING MERGE 11

purposeful activity. Studies associate volunteerism, forinstance, with lower rates of mortality and depression,increased strength and energy, decreased symptomsof depression, and delayed physical disability.2Purpose—engagement and working toward goalsas we age—is important for longevity as well as vitality,productivity, and lower rates of cognitive decline,stroke, and heart attack.3“We have a tremendous opportunity to improvepublic health if we can get older people engaged,feeling purposeful and more proactive,” says neuropsychologist Patricia Boyle of the Rush Alzheimer’sDisease Center at Rush University Medical Center.“The potential health and economic benefits ofincreasing purpose in older persons are likely huge.”TROUBLING SIGNSBy Laura CarstensenThe timing of the purposeful aging movement is critical. Sobering findings from the StanfordCenter on Longevity’s Sightlines project add urgency and a potential red flag: 55-to-64-year-oldsare less socially engaged now than their predecessors were 20 years ago. They are less likely tobe married or involved in religious organizations. They don’t interact as much with neighbors andhave weaker ties to family and friends.Traditional modes of engagement are waning for all age groups, but the greatest decline isamong those on the cusp of old age. While it’s not clear if workplace or online socializing maybe compensating for these shortcomings, the startling findings have serious implications for ouraging society. Social engagement is a key to improving health and longevity, and it is critical forsocieties to utilize the human capital represented in older citizens.Feeling connected to others is crucial to physical and mental health. More than ever, it’simportant that people between middle and advanced age flourish psychologically, physically,spiritually, and intellectually. Finding purposeful engagement may be just what aging adultsneed, as research suggests that volunteering promotes overall well-being.Because of the size of the boomer cohort, the norms they set will not only have short-termramifications, but may endure for generations. A great deal is at stake. If boomers establishexpectations about giving back to communities and investing in younger generations, theycan put the United States on track to become a better nation. In contrast, if they bow out andwithdraw—as our Sightlines project suggests they may—we risk a dimmer future.12Older individuals want a sense of purpose in theirremaining years; they want to contribute.4 Enjoying anadditional three decades of life, on average, comparedto what our forebears could expect at the start of the20th century, today’s aging adults have the time toexplore those goals. Indeed, the nation and the worldcan benefit from their engagement: Issues of race,gender, and religion divide us; inequities in educationand justice constrain the potential of so many youngpeople; political and social institutions need repair; andpolicymakers can’t seem to find solutions. Beneficiallyengaged older adults can help fill the gaps.“We need the assets of our many older people to makeour nation stronger: their experience and expertise,their ability to analyze problems and help fix them, theircontinued desire to leave the world a better place,and their time,” states Linda Fried, dean and DeLamarprofessor of public health at the Mailman School of PublicHealth at Columbia University. She adds: “An importantkey to aging successfully is feeling that our lives are meaningful, that we have created something that will endurebeyond us. At every age we need some structure in ourlives and a reason to get up in the morning. Without it,sickness and earlier death are more likely.”Missing the BoatHowever, our cultural frames of reference have not caughtup to reality, with scant recognition of older individuals’potential. Long established and uninformed stereotypesshroud aging behind a negative lens that celebrates allthings young while overlooking scientific evidence aboutthe strengths of older adults. Virtually all forms of mediaand messaging reinforce these misperceptions.Older adults are not done with the world, but the world,cocooned in a culture that extols the virtues of youth,may be done with them. Ready for new beginnings,they are routinely shuffled to the sidelines and theshadows of decline. If older adults are to find meaningful roles that fulfill their enormous potential, attitudesmust change.This is a powerful story about promise for societieseverywhere, but it is obscured by a culture bound topre-21st century ideas. We need fresh ways to frameand communicate this story. We need a movement tomake the case for purposeful aging that can enrich usall, a movement that upends cultural assumptions.At the same time, we can accelerate the worthy butpiecemeal efforts that already promote purposefulaging. We can build up pathways for encore careersand support successful programs like AARPFoundation’s Experience Corps, the federal SeniorCorps, and other impactful examples of older peoplemaking a difference. We can advocate for additionalresources to spread and scale effective programs. Wecan enhance awareness and understanding throughstorytelling and media strategies.Setting the TrendIntergenerational conversations and collaboration—theengagement of millennials, Gen-Xers, baby boomers,and the Greatest Generation alike—are an importantpart of this movement. All will gain when older peopleare enabled to live with purpose.There’s much at stake for the future. The way today’saging adults interact with their communities, and thevalues and priorities they uphold, will set patterns forthose who come after them—generations that areexpected to enjoy even longer lives. By setting newnorms for serving others, they are defining a coursethat can lead to a better world.5The 21st century challenges older people to invent thisnew world of aging with purpose. With the opportunities of extended longevity ahead, baby boomers muststep up and join in efforts to redefine this stage of liferather than accepting yesterday’s norms. Summoningtheir sizable reserves of confidence and creativity, theycan establish a new era of aging as a multifaceted,productive experience.CHAPTER 1: WHEN PURPOSE AND AGING MERGE 13

We need the assets of our manyolder people to make our nationstronger: their experience andexpertise, their ability to analyzeproblems and help fix them, theircontinued desire to leave the worlda better place, and their time.PURPOSE IN ACTIONLINDA FRIEDJEANNE PINDERFounder and CEO, ClearHealthCosts.comJeanne Pinder founded ClearHealthCosts.com to help people grapple withone of the nation’s biggest problems—medical costs, and the confusionaround why a simple colonoscopy costs 913 in one place and 2,700 inanother. The lifelong journalist left the New York Times and launched acompany that gathers and posts individual providers’ prices, making adifference for people who may even forgo medical care, believing theycan’t afford it. “People need help on this,” Pinder says. “And journalists likeus are the right people to do it.” Starting in New York with grant funding,ClearHealthCosts.com has expanded into three additional markets. Pinderhelps sustain the growing business by developing and providing softwareservices and through editorial consultation with partners. ClearHealthCosts.com1415

We must shift the narrative fromfear and denial to an embrace ofaging, move from a back-to-youth orregression orientation to a purposefulnew way of being, and move fromolder people being a burden to beingan asset to society as a whole.AI-JEN POO1617

7.5A HEALTHY SELF-IMAGESeven and a half years—that was the longevity boostfor study participants who had positive self-perceptionsof aging, compared to those without. And peoplewho scored high on a purpose assessment fended offAlzheimer’s disease better than low scorers.PURPOSE IN ACTIONBEV BARTLETTMemory Cafe VolunteerAfter a career that began with teaching, then progressed to positions withlocal aging commissions and the Alzheimer’s Association, Bev Bartlett“retired” and asked herself, “What am I going to do with the rest of my life?”Today the 71-year-old serves on several aging-related committees andvolunteers about 15 hours a week in Brown County, Wis., at “memory cafes,”which enable dementia sufferers and their caregivers to gather and socialize.Her husband is a volunteer also, and Bartlett says their service enhancestheir relationship. “I found people are much happier when they have something to give, and I’m receiving much more than I get. My volunteer workmakes me feel better about myself.” Alzheimerscafe.comSource: Becca R. Levy et al., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.1819

CHAPTER 2THECASE FORPURPOSEFULAGINGScience increasingly holds thatthe new world of aging makespurpose a logical, productive,and obvious imperative.Research tells us that:With maturity, people develop an intrinsic urge togive backThe attributes of older people mesh neatly with theneeds of youthPurpose is tied to older adults’ physical and mentalwell-being, and even mortalityAn engaged older population provides economicbenefits, from workplace, taxation, and consumerimpacts to the value of charitable and volunteer workThe generative impulse manifests as a drive to leavea positive legacy. Aging adults seek to address theneeds of successor generations in a range of ways andshare their wisdom for the welfare of future societies.Evidence finds that the benefits of their service also aremutual. Studies demonstrate that in doing good forothers, people accrue physical and mental advantagesthemselves. Research also suggests that generativity isa cornerstone of successful aging, linked to satisfactionand overall well-being in later life.6The shortening of life’s horizons refocuses older peopleon mental processes that facilitate happiness. Theaging brain actually improves in many ways, includingin complex problem-solving and emotional stability—with intense moods giving way to larger perspectivesand nuanced viewpoints.7 This mental maturity often islinked to “wisdom,” which is a key to successful relationships and is associated with greater life satisfactionand longevity.8The arrival of the largest-ever older population at alife stage that deepens wisdom and strengthensemotional balance, enhanced by the extensiveeducation, experience, and skills of today’s aginggeneration, raises hopeful prospects. If we channelthese qualities, we can imagine vast possibilitiesfor purposeful activity to improve lives, civic andcharitable organizations, companies and economies,while embracing a self-reinforcing and vibrantolder population.WHAT IS GENERATIVITY?When people move through middle adulthood, they begin to experience an impulse to “pass thetorch” and use their knowledge, skills, and experience to improve life for future generations. Theinfluential psychoanalyst Erik Erikson defined this urge as “generativity,” in effect a motivationto contribute to a better tomorrow.The pattern dovetails with Laura Carstensen’s theory of socioemotional selectivity, which holdsthat personal perceptions of time, specifically life’s shortened horizons, play a fundamental rolein how people select and pursue social goals. Seeing the years behind them stretching longerthan the years ahead, they prioritize their activities, take a keener interest in the world outsidethemselves, and balance their emotions with greater wisdom. Things that were once stressful,they can now take in stride.20CHAPTER 2: THE CASE FOR PURPOSEFUL AGING 21

Good That Is Good for YouVolunteering is not the only pathway to purposefulliving—people also find meaning and purpose at workand through family relationships and social activities—but research on volunteerism identifies it as an essentialingredient in the recipe for healthy aging. A study of intergenerational volunteerism found thatolder adults enjoyed a heightened sense of well-beingfrom their interactions with youth. Older volunteersassociated successful aging with staying active, notworrying about problems, feeling young, and keepingup with children and the community.9 Older volunteers in a 2013 study experiencedreduced risk of hypertension, delayed physicaldisability, enhanced cognition, and lower mortality.While the mechanisms of these correlations werenot clear, researchers Dawn Carr, Linda Fried, andJohn Rowe identified the physical activity, cognitiveengagement and social interaction aspects of volunteerism as contributing factors. It is especially strikingin this research that while people who volunteer typically are thought to be wealthier, healthier, and moresocially connected, many people from groups loweron the socioeconomic ladder, including older adults,regularly volunteer in their communities. And thesevolunteers exhibit disproportionately greater benefitsfrom their service.10 Harvard Medical School professor George Vaillantfound that older people who achieved generativitythrough activities such as mentoring and supportingyounger people were three times as likely as theiruninvolved peers to experience joy instead of despairas they moved through their 70s.11 A three-year study found that in the federallysupported Foster Grandparents program, an armof Senior Corps, 71 percent of foster grandparentsreported almost never feeling lonely, compared to 45percent of people who were on a waiting list to jointhe program.12 UnitedHealth Group concluded in a 2013 surveythat volunteerism is an important part of a healthylifestyle, especially for older people. Survey respondents linked their volunteering to physical, mental,and emotional well-being. More than nine in 10 saidvolunteering improved their mood. Nearly eight in 10said it lowered their stress levels, and three-quarters22said it made them feel physically healthier. About aquarter of them even said that volunteering helpedthem manage their chronic illnesses.13 “Doing good isgood for you,” UnitedHealth Group concluded in itsreport. “In all of the pathways we take to good health,being a volunteer can help to make a meaningfuldifference.”Purpose and Alzheimer’sWhat about the illness that especially terrifies peopleover 65—Alzheimer’s disease?14 Implications of thecondition are well known, and many people haveexperienced the front-row agony of watching someoneclose fade into severe cognitive decline. A cure forAlzheimer’s and other dementias remains elusive, evenas population aging expands the flow of cases into atorrent. One in nine Americans age 65 and over nowsuffers from Alzheimer’s, and by age 85, one-thirdare affected.15 Without a medical breakthrough, thenumber will skyrocket to at least 14 million by midcentury, up from 5.2 million now.16 The impacts areprojected to be even greater in societies that are agingfaster than America. Alzheimer’s represents a pressingglobal problem.While cure is certainly the goal, any effective intervention would be of great value. Here again, the case forpurpose is compelling.Scientists have discovered that purposeful activity notonly can slow cognitive decline, but also may delay theonset of Alzheimer’s and buffer its effects on the brain.These findings emerged when Patricia Boyle and hercolleagues at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Centerinterviewed older adults about purpose in their lives,conducted cognitive testing and neurological exams,and examined brains postmortem for evidence ofAlzheimer’s. They found that higher levels of purposereduced harmful cognitive effects and slowed the rateof decline by about 30 percent, even when the brainalready exhibited the disease’s damaging plaques andtangles.17A separate longitudinal study spearheaded byBoyle found that people who reported having greaterpurpose in life were 2.4 times more likely to remainfree of Alzheimer’s than those with lower self-reportedpurpose scores.18The science clearly indicates wehave an opportunity to improve publichealth by helping older persons remainengaged and purposeful. We needto harness that, to let people knowthat having purpose helps people livelonger and better and that there’s abiologic basis for health-protectiveeffects of purpose in life. People don’tthink purpose affects our biology, butscience says it does. We need to betterunderstand exactly how—and for that,we sorely need funding.PATRICIA BOYLETo give these results context, it is important to note thatscience currently has no way to keep dementia-relatedCHAPTER 2: THE CASE FOR PURPOSEFUL AGING 23

pathology from accumulating: Nearly all older peoplehave some evidence of Alzheimer’s changes in theirbrains. Finding a way to mitigate its effects would beakin to discovering a magic pill.Benefits for Young and OldThe benefits of intergenerational activity are particularly striking for both young and old. We know thatpurposeful engagement is good for older people. Aswell, the very qualities they possess—the often-overlooked attributes that accompany this life stage—arewell-suited to the needs of the younger generation,especially vulnerable children who have suffered stressor trauma, according to emerging research. Experienceand empathy equip older adults for roles as tutors,mentors, coaches, and pillars of family support.19The long-term results of such interaction canbe dramatic. Scholars who study the obstaclesconfronting young people say that a key ingredient offuture success is the steady presence of caring adultscommitted to their development.20“While the needs and desires of older adults mayappear to be a world apart from those of young people,at both ages, finding purposes to pursue can promoteenergy, resilience, life satisfaction, achievement, andhealth,” says William Damon, professor of education atStanford University. “In our studies at Stanford, we havefound that the most important support for a youngperson’s search is having an older adult mentor whomodels a

1 When Purpose and Aging Merge 10 2 The Case for Purposeful Aging 20 3 Challenges on the Path 32 4 Communicate, Convince, Connect 46 Conclusion 58 Endnotes 59 Board of Advisors 62 THE POWER OF PURPOSEFUL AGING Culture Change and the Ne