Transcription

ON THE PATH TO EQUITY:IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESSOF BEGINNING TEACHERSJULY 2014INDUCTIONCAPACITYPRACTICECONDITIONSC O L L A B O R AT I O NLEADERSHIP

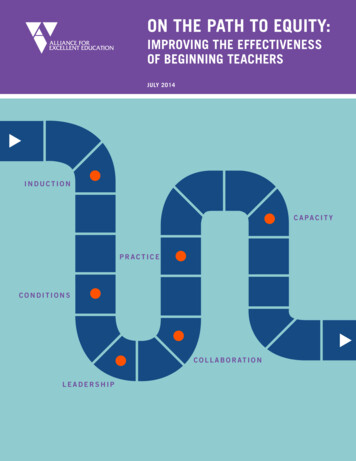

SUMMARYA new policy and economic environmentpromises to upend the twentieth-century blueprintfor high schools that has left large numbers ofstudents without diplomas or the advanced skillsessential for college and careers. To preparegraduates for a twenty-first-century societyand a global workplace, most states adoptedthe Common Core State Standards or otherinternationally benchmarked college- and careerready standards. Long-standing concerns remain,however, about whether states have an educatorworkforce, or the capacity to produce one, withthe training and skills needed to ensure thatstudents achieve the learning outcomes essentialto succeed in school and beyond. If the dominantteacher workforce policies and practices remainINTRODUCTIONTo achieve a fundamental transformation of educationand help students meet the higher performance set by thecommon core standards, the very culture of how teachersunchanged, then the aspirations of rigorousare supported must change. This will require coherentstate standards will simply continue a legacy ofincentives and structures to attract, develop, and retainunfulfilled reforms.the best teaching talent in high schools serving studentsThe good news is that multiple initiatives are now underway to develop professional standards for beginningteachers, strengthen preparation, and shape strategiesto address the developmental needs of teachersthroughout their career. This report highlights the workof New Teacher Center (NTC), a national nonprofitorganization headquartered in Santa Cruz, California,that has partnered with states, districts, and policymakersto develop programs and policies that accelerate newteacher effectiveness. NTC focuses on hard-to-staffschools that serve low-income students and students ofcolor, where high rates of teacher turnover tend to be moreprevalent and a disproportionately high percentage of newteachers are often employed.with the greatest needs. The challenge of preparing allstudents for the modern workplace rests with developingthe collective capacity of an entire profession to addressthe needs of all learners. Teaching conducted largely outof the sight and hearing of other teachers must ceaseto be the norm. A new paradigm is needed for powerfulsystems of professional learning by which a clear visionof effective teaching informs the entire program and newteachers receive comprehensive induction and access toschool-based collaborative learning.Teaching quality is recognized as the most powerfulschool-based factor in student learning. It outweighsstudents’ social and economic background in accountingfor differences in student achievement.1 Moreover,ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG1

analyses of longitudinal data sets reveal that teachersexert an accumulating influence: a series of superiorteachers can overcome the learning deficits between13%low-income students and their more advantaged peers.Likewise, the residual effects of having ineffective teachersover multiple years are devastating.2Unfortunately, commitment has rarely existed across stateAbout 13 percent of theAmerican workforce of 3.4million public school teacherseither moves (227, 016)or leaves (230,122) theprofession each year.Share this stat: #all4edand district lines to ensure all students equitable accessto effective teaching. Research shows chronic gaps indisadvantaged students’ access to effective teaching bothbetween and within schools. In addition, a recent Instituteof Educational Sciences study shows that districts rarelyuse data on teacher effectiveness to determine students’access to effective teaching throughout the system. The3variation in teaching quality is most acute in high schoolsthat serve low-income students and students of color.Disparities in the distribution of skilled teachers placed inhigh-need high schools have persisted despite provisionsto ensure teacher equity in the last reauthorization ofthe Elementary and Secondary Education Act, known asthe No Child Left Behind Act. Schools serving urban andpoor students are more likely to employ teachers who areon emergency waivers and who are not certified in thesubject they teach.4 Disadvantaged students have only a50 percent likelihood of being taught math and science byteachers who hold a degree and a license in the field inwhich they teach.5 Persistent inequities in the distributionof quality teaching lay to waste historic promises of equaleducation opportunity.Students are not the only ones whose ability to learnsuffers in low-performing schools. Too often, teachers inschools serving students from high-need environmentslack access to excellent peers and mentors and havefewer opportunities for collaboration and feedback.Moreover, without opportunities to engage with others toexamine and improve instructional practices, teachers’performance in high-poverty schools plateaus after a fewyears.6 In these lowest-performing high schools, moraleand work environment suffer because hard-to-staff schoolsbecome known as places to leave, not places in whichto stay.About 13 percent of the American workforce of 3.4 millionpublic school teachers either moves (227,016) or leaves(230,122) the profession each year.7 The high annualturnover rates seriously compromise the nation’s capacityto ensure that all students have access to skilled teaching.Researchers estimate that more than one million teachers,including new hires, transition into, between, or out ofDisparities in the distribution of skilled teachers placed in high-need highschools have persisted despite provisions to ensure teacher equity inthe last reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act,known as the No Child Left Behind Act.ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG2

schools annually.8 High-poverty schools experience aSince the mid-1980s the significantexpansion of the teaching workforcehas been accompanied by increasedturnover among beginning teachers.teacher turnover rate of about 20 percent per calendaryear—roughly 50 percent higher than the rate in moreaffluent schools.9 The estimate of the percentage of newteachers leaving teaching after five years ranges from 40percent to 50 percent, with the greatest exodus takingSince the mid-1980s the significant expansion of theplace in high-poverty, high-minority, urban, and ruralteaching workforce has been accompanied by increasedpublic schools.10 The cumulative costs of attrition of thoseturnover among beginning teachers. The annual attritionleaving teaching altogether are high. Richard Ingersoll,rate for first-year teachers has increased by more thanprofessor of education and sociology at the University of40 percent over the past two decades.12 The influx of newPennsylvania, estimates that states spend betweenteachers has neither stabilized the teaching workforce nor 1 billion and 2.2 billion a year on teacher attritionimproved teaching quality. In 1987–88, the modal, or mostturnover. (See Appendix A for state-by-state attritioncommon experience level, was fifteen years; by 2008, thecosts.)11 Studies suggest that the price tag for recruitmenttypical teacher was in his or her first year of teaching.13and replacement seriously underestimates the cumulativeBecause the economic downturn beginning in 2007–08costs of eroding the caliber and stability of the teacherslowed the rate of increase in the number of beginningworkforce, particularly in chronically underperformingteachers, by 2011–12 the modal teacher was someone inschools serving the neediest students.his or her fifth year.14Teaching Experience of School Teachers,1987–88, 2007–08, and 2011–12Number of 0100,00050,000016111621263136414651566166Years of ExperienceSource: R. Ingersoll, L. Merrill, and D. Stuckey, Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force, CPRE Report (#RR-80) (Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education,University of Pennsylvania, April 2014).ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG3

WHY IS TURNOVER SO HIGH?Ingersoll and his colleagues found that there is an annualreshuffling of significant numbers of employed teachersfrom poor to non-poor schools, from high-minority to lowminority schools, and from urban to suburban schools.15Teachers departing because of job dissatisfaction link theirdecision to leave to inadequate administrative support,isolated working conditions, poor student discipline, lowsalaries, and a lack of collective teacher influence overNew teacher retention rates varywidely among schools serving similarstudent populations, suggesting thatdifferences in school climate stronglyinfluence teacher turnover.conditions are well-suited for them to have the potential tobe effective.”19schoolwide decisions.16 Ingersoll writes, “In short, theStudies on working conditions and school context indicatedata suggest that school staffing problems are rooted inthat current teacher development and appraisal policiesthe way schools are organized and the way the teachingare unlikely to advance the national goals for improvingoccupation is treated and that lasting improvements in theteaching effectiveness and preparing students for thequality and quantity of the teaching workforce will requiremodern workplace if they fail to address these rootimprovements in the quality of the teaching job.”17causes.20 Susan Moore Johnson, the Jerome T. MurphyUnderscoring these conclusions is a Consortium onChicago School Research (CCSR) report on teachermobility in Chicago Public Schools, which shows thatmany schools serving low-income, minority students turnover half of their teaching staff every three years.18 Evenso, new teacher retention rates vary widely among schoolsserving similar student populations, suggesting thatdifferences in school climate strongly influence teacherturnover. The CCSR report notes, “Schools with highstability cultivate a strong sense of collaboration amongteachers and their principal. Teachers are likely to stay inschools where they view their colleagues as partners withthem in the work of improving the whole school and theProfessor in Education at Harvard University, writes, “Thiswork suggests that school context matters Reformerswho seek to increase opportunity and resilience amongdisadvantaged students would do well to think beyond theindividual teacher and address the differences in schoolsas places for teaching and learning.”21 Since the 1990s,studies have identified the benefits of organizationalstrategies that foster higher levels of teacher collaborationand peer learning.22 This research shows that socialcapital—the pattern of interactions among teachers andadministrators focused on student learning—affectsstudent achievement and school success across all typesof schools and grade levels.23Social capital—the pattern of interactions among teachers andadministrators focused on student learning—affects student achievementand school success across all types of schools and grade levels.ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG4

90 %Ninety percent of teachers believe that they share responsibility forstudent achievement, their success is linked to that of their colleagues,and increased collaboration in schools would have a major positiveeffect on student achievement.Share this stat: #all4edBuilding the collective capacity for strong high schoolwith a teacher’s decision to invest effort in acquiring newperformance requires creating a school climate ininstructional skills. They found that positive spilloverswhich it is assumed that the improvement of teachingare strongest for less-experienced teachers who areis a collective rather than individual enterprise. Asstill acquiring “on-the-job” skills, and that both past anddocumented in the 2009 MetLife Survey of the Americancurrent differences in peer quality affect current studentTeacher: Collaborating for Student Success, 90 percentachievement.27 Because accruing expertise has long-termof teachers believe that they share responsibility foreffects, the cumulative exposure to peers proves to be astudent achievement, their success is linked to that of theirpowerful predictor of improved student achievement.24colleagues, and increased collaboration in schools wouldhave a major positive effect on student achievement.25Short-term, replacement strategies treat teachers likeinterchangeable, expendable parts rather than asTeachers are more likely to change their teachingyoung professionals meriting sustained investmentspractices and improve student learning in the presence ofin their development as part of a community of expert,effective peers. C. Kirabo Jackson and Elias Bruegmannexperienced teachers. Many administrators and teacherfound that an individual teacher’s students have largereducators conclude that the lack of well-supervised clinicalachievement gains in math and reading when othertraining throughout preparation and during the initial yearsteachers in the schools are more effective.26 The authorsof teaching accounts for many of the problems facing newconcluded that the effects were due to peer learning alongteachers. Daniel Fallon, professor emeritus of public policyand psychology at the University of Maryland, writes, “Theonly preparation that most beginning teachers had wasthe semester-long student-teacher experience. This wasnot sufficient. Student teachers had not survived a seriesof instructional failures, experienced students’ boredom,discovered a wall of student learning resistance, or felt theisolation of ‘teaching forever.’ ” Teachers need from three toseven years in the field to become highly skilled—with theanalytic and flexible thinking needed to engage learners,deepen their conceptual understanding, and respond tohow well they are learning.28ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG5

IMPACT OF INDUCTIONOver the past two decades, research shows that retentionis closely related to the quality of the first teachingexperience.29 Analyses of the Schools and StaffingSurvey (SASS) and the Teacher Follow-up Survey(TFS), administered by the National Center for EducationStatistics, established the correlation between the level ofsupport and training provided to beginning teachers andtheir likelihood of moving or leaving after their first year.30In a similar vein, the Project on the Next Generation ofTeachers at the Harvard Graduate School of Educationfound that new teachers’ decisions to transfer out ofstates require some kind of induction program, few providelow-income schools were related to the extent to whichthe majority of beginning teachers with all four of the mostthose schools supported them by providing well-matchedcommon components: mentoring, reduced preparation/mentors, valuable induction programs, and appropriatecourse load, seminars/workshops, and supportivecurricular guidance.31communication with a principal or department chair.34A growing number of states have induction supportDespite the progress states have made in offeringprograms in place for beginning teachers—programs thatinduction opportunities, access to induction supportseducation researchers have been calling for since theremains inequitable, with teachers in schools with the1970s.32 Beginning teachers reporting that they have ahighest concentrations of poor and minority studentsmentor or master teacher working with them during theirreporting significantly lower participation rates in inductionfirst year have increased from about 50 percent in 1990 toand mentoring.35 This troubling support gap for teachersover 90 percent as of 2008.33 Even though the number ofis pervasive in low-income schools, where fewer teachersstates that currently require, and in some measure fund,have mentors than their counterparts in more affluentinduction programs for new teachers has continued toschools. Those who do have mentors are less likely toclimb, the overall character and content of these programsbe paired with an experienced teacher in the samevary widely, including duration, intensity, frequency ofschool, grade, or subject, and mentoring discussions—mentoring, training and criteria for mentor selection, andwhen they occur—are less likely to focus on issues ofcompensation for mentoring. Although more than half ofclassroom teaching.36Access to induction supports remains inequitable, with teachers in schoolswith the highest concentrations of poor and minority students reportingsignificantly lower participation rates in induction and mentoring.ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG6

THE CASE FORCOMPREHENSIVE INDUCTIONA review of selected, well-designed empirical studiesconducted since the 1980s shows positive effectsof induction for beginning teachers.37 As inductionhas become more widespread, most of the studieshave compared teachers according to their degree ofparticipation in one or more induction components.The induction elements producing the strongesteffects include having a mentor from the same field,scheduled collaboration with other teachers, and regularcommunication with one’s principal.38 When the numberof support measures increase, attrition rates for beginningteachers decline, they perform better at various aspectsof teaching, and, most significantly, their studentshave higher scores or greater gains on academicachievement tests.39Overall, teachers receiving a more comprehensivepackage of these induction components achieve higherlevels on all three outcomes:The induction elements producingthe strongest effects include havinga mentor from the same field,scheduled collaboration with otherteachers, and regular communicationwith one’s principal.A comprehensive induction program that comprisesmultiple types of support, such as high-quality mentoring,common planning time, and ongoing support from schoolleaders, reduced by one-half the turnover rate of thosereceiving induction in comparison to those receivingnone.40 However, few beginning teachers currentlyreceive the ongoing training and support that constitutescomprehensive induction. Only about half of novicesreceive mentoring from a teacher in their teaching field orhave common planning time with other teachers.41Many questions remain on specific aspects of inductionand on the factors that produce differential effectsof induction between low- and high-poverty schools.For example, mixed effects for new teacher induction teachers’ job satisfaction, commitment, and retention; teachers’ classroom teaching practices andschools may be attributable to substantial differences inpedagogical methods; andthe quality of programs, the organizational context, and the student achievement.programs in high-poverty schools compared to low-povertynature of instruction and teaching practice. New teachersin high-poverty schools must frequently follow prescriptivedistrict mandates regarding what they teach and howthey teach along with extensive requirements for testpreparation. Researchers and teacher educators questionwhether an induction program can simultaneously promotea teacher’s skill in engaging students in higher-orderinquiry while also emphasizing his or her ability to preparestudents for narrowly focused, standardized testing.42ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG7

FOSTERING POSITIVECONDITIONS FOR TEACHINGAND LEARNINGComprehensive InductionThe cumulative research on induction offers aWhile proving increasingly important to teacher retentionstrong argument for providing beginning teachersand quality, induction that is not part of a more systemicwith a comprehensive package of supports.approach to professional learning may be insufficient to“Comprehensive induction” combinesreduce the high levels of teacher turnover found in many urban, low-income public schools. Overall the qualityhigh-quality mentoring with rigorous mentorselection criteria;of professional development has failed to keep pacewith the enormous changes in the student population and the diversity of their learning needs. Between 1980common planning time for regular scheduledinteraction with other teachers;and 2009, the number of school-age children, ages five through seventeen, who spoke a language other thanparticipation in seminars and intenseprofessional development; andEnglish at home more than doubled, from 4.7 million (10 percent) to 11.2 million (21 percent).43 According to Theongoing communication and support fromschool leaders.MetLife Survey of the American Teacher: Past, PresentSource: R. Ingersoll and M. Strong, “The Impact of Induction and MentoringPrograms for Beginning Teachers: A Critical Review of the Research,” Reviewof Education Research 81, no. 2 (2011): 201–33.and Future, almost half of secondary school teachers saythat students’ learning abilities have become so mixedin their classrooms that they cannot teach effectively.44Data from multiple sources shows an overall patternof poorly designed and implemented professionalimprovement practices even in states where policies onstaff development exist.45The good news is that multiple initiatives are now underway to develop professional standards for initial licensure,strengthen preparation, and shape strategies to addressthe developmental needs of teachers throughout theircareer. New Teacher Center is one of the most prominentexamples in the country, and one with which teachers andpolicymakers should be well acquainted as they work toimprove teacher effectiveness. It has established a welldesigned, evidence-based induction model for beginningteachers to increase teacher retention, improve classroomeffectiveness, and advance student learning.NTC’s teacher induction model—implemented in morethan forty states and U.S. territories—provides multiyear, structured mentoring and intensive professionaldevelopment differentiated to meet beginning teachers’Almost half of secondary schoolteachers say that students’ learningabilities have become so mixed intheir classrooms that they cannotteach effectively.needs.46 Since 1998, NTC has partnered with states,districts, and policymakers to develop programs andpolicies that accelerate new teacher effectiveness. NTC’swork is particularly important in hard-to-staff schoolsthat serve low-income and minority students, whereON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG8

NTC’s comprehensive mentor-based teacher induction includes multi-year assistance for at least two years, with multi-support design; carefully selected, well-prepared, and systematicallyengaged principals who know how to create conditionsthat support teacher development; program leadership collaboratively shared among allsupported mentors who focus on instruction andstakeholders, including district administration and union/student learning;association leaders; andongoing formative assessment of the teacher’s practice strong alignment with other district goals that supportto guide learning experiences and professional goalteacher learning (e.g., evaluation, tenure, professionalsetting;learning communities).sanctioned time for targeted professional developmentactivities and for mentors and beginning teachers towork together, observe practice, and analyze studentlearning data;teacher turnover tends to be more prevalent and aAs NTC’s Review of State Policies on Teacher Inductiondisproportionately high percentage of new teachers areshows, most state policies lack a strong commitmentoften employed.to high-quality induction and mentoring.47 Too few stateNew teacher induction has the greatest impact when itis thoughtfully integrated into a broader vision of howschools, districts, and states define, measure, and improvethe performance of all teachers. Principals are responsiblefor leading the creation of supportive working conditionsand have a lead role in teacher development, evaluation,and school improvement. For this reason, NTC partnerswith districts to provide job-embedded executive coachingand professional development for school leaders. It isdesigned to support instructional leadership and build astrong connection between new teacher induction andschool and district goals.policies envision teacher induction as part of a system ofteacher development, establish quality program standards,help identify and train effective mentors, or generally offerdistricts the guidance and resources to provide meaningfulnew teacher support. NTC works with its district andstate partners to build systemic opportunities for newteachers to develop teaching practice and continuouslyimprove. School leadership, teaching conditions (includingopportunities for teacher leadership and collaboration),customized development opportunities, and teachingpolicy all greatly impact new teachers’ chances of successand the impact of induction programs designed toaccelerate their development.ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG9

NTC’S TEACHING ANDLEARNING CONDITIONSINITIATIVENTC also partners with states and districts to surveyteaching and learning conditions to the full populationof school-based licensed educators using its Teaching,Empowering, Leading, and Learning (TELL) survey.The TELL survey assesses the perceptions of teachers,principals, and other licensed educators about thepresence of supportive teaching and learning conditionsthat research shows is important to student achievementand teacher retention. All teachers perform better inschools with supportive leadership and a collaborativeculture for improving practice and student learning, andwhere they have sufficient time and resources. The surveycaptures data regarding the following conditions:In addition, NTC conducts an array of analyses basedon the TELL results and other data sets customized foreach state or district client. These may include analyses ofinduction programs in persistently low-performing schools,comparisons based on particular factors such as years ofexperience or differences in perceptions among groups ofeducators, and/or how survey data correlates with student time; facilities and resources; professional development; school leadership;teaching and learning conditions. teacher leadership;For example, in 2010, with the leadership of Governor instructional practices and support; managing student conduct;use survey data on teaching conditions as part of the community support and involvement; anddesign of school improvement initiatives. The 2011 TELL new teacher support for teachers in their first threeyears in the profession.achievement data. Additionally, NTC provides web-basedtools for schools and districts to use in analyzing theirTELL results to help identify strategies for improvingSteve Beshear and Commissioner Terry Holliday, theKentucky state legislature required that the state agencysurvey revealed low overall means for persistently lowperforming district schools in two areas: communitysupport and involvement, and managing student conduct.NTC provides each state and district with TELL surveyThese two areas, which showed the greatest connectionfindings as well as the results for each school that meetsto student achievement in 2011, became the focus ofthe required minimum response rate threshold to ensureimprovement efforts. Findings from the second TELLconfidentiality (generally 50 percent). Working at both theadministration in 2013 showed that there was consistentstate and district levels, NTC has received over one millionimprovement among the targeted schools in these twosurvey responses in more than twenty states since 2009.survey areas and that the gain exceeded improvement fornon-targeted district schools.48ON THE PATH TO EQUITY: IMPROVING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BEGINNING TEACHERSALL4ED.ORG10

NTC’S CROSS-STATEANALYSES 2012–13NTC encourages states to involve teachers,In 2013, NTC released Cross-State Analyses of ResultsThe goal is to help states use the survey data to develop2012–2013: Research Report 2013 TELL Survey tocoherent policies and practices that connect relatedprovide an additional contextual lens for states to betterfactors such as school leadership, teaching and learningunderstand and interpret their own survey findings onconditions, and specific educator policies. It integratesteacher working conditions. The analysis comparesthe focus on teaching and learning conditions withresponses from almost 365,000 educators acrossother teaching effectiveness initiatives and specificallynine states: Colorado, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland,with induction programs designed to accelerate newMassachusetts, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, andteacher development.superintendents, and community and business leadersin working collaboratively to use the survey findings.Vermont. Overall findings show that educators fromKentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee report meansconsistently at or above a 3.0—higher than the overallaverage for the nine states—with the exception of thearea of time. The lowest means across all states were forthree survey areas: instructional practices and support;As a result, state policymakers have begunto use the TELL survey data in various waysto change teaching and learning conditionsas part of broader reform efforts that include standards (NC, KY);50professional development; and time, which was perceivedby educators across all states as the condition with the most constraints. Reports on the TELL survey data forindividual states are available through publicly accessiblewebsites dedicated to each state.49development and adoption of state teaching conditionsinclusion of TELL data in principal evaluationprograms (DE, KY, NC, TN); use in principal pr

public schools.10 The cumulative costs of attrition of those leaving teaching altogether are high. Richard Ingersoll, professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, estimates that states spend between 1 billion and 2.2 billion a year on teacher attrition turnover. (See Appendix A for state-by-state attrition