Transcription

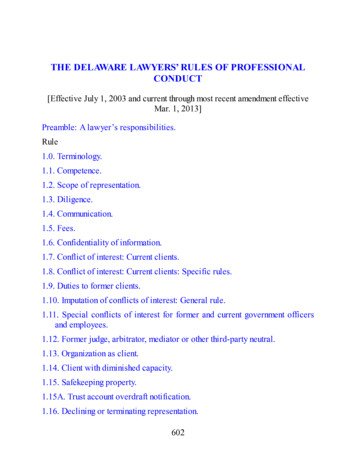

THE DELAWARE LAWYERS’ RULES OF PROFESSIONALCONDUCT[Effective July 1, 2003 and current through most recent amendment effectiveMar. 1, 2013]Preamble: A lawyer’s responsibilities.Rule1.0. Terminology.1.1. Competence.1.2. Scope of representation.1.3. Diligence.1.4. Communication.1.5. Fees.1.6. Confidentiality of information.1.7. Conflict of interest: Current clients.1.8. Conflict of interest: Current clients: Specific rules.1.9. Duties to former clients.1.10. Imputation of conflicts of interest: General rule.1.11. Special conflicts of interest for former and current government officersand employees.1.12. Former judge, arbitrator, mediator or other third-party neutral.1.13. Organization as client.1.14. Client with diminished capacity.1.15. Safekeeping property.1.15A. Trust account overdraft notification.1.16. Declining or terminating representation.602

1.17. Sale of law practice.1.17A. Dissolution of law firm.1.18. Duties to prospective client.2.1. Advisor.2.2. [Deleted].2.3. Evaluation for use by third persons.2.4. Lawyer serving as third-party neutral.3.1. Meritorious claims and contentions.3.2. Expediting litigation.3.3. Candor toward the tribunal.3.4. Fairness to opposing party and counsel.3.5. Impartiality and decorum of the tribunal.3.6. Trial publicity.3.7. Lawyer as witness.3.8. Special responsibilities of a prosecutor.3.9. Advocate in nonadjudicative proceedings.3.10. [Deleted].4.1. Truthfulness in statements to others.4.2. Communication with person represented by counsel.4.3. Dealing with unrepresented person.4.4. Respect for rights of third persons.5.1. Responsibilities of partners, managers, and supervisory lawyers.5.2. Responsibilities of a subordinate lawyer.5.3. Responsibilities regarding non-lawyer assistance.5.4. Professional independence of a lawyer.5.5. Unauthorized practice of law; multijurisdictional practice of law.603

5.6. Restrictions on right to practice.5.7. Responsibilities regarding law-related services.6.1. Voluntary pro bono publico service.6.2. Accepting appointments.6.3. Membership in legal services organization.6.4. Law reform activities affecting client interests.6.5. Non-profit and court-annexed limited legal-service programs.7.1. Communications concerning a lawyer’s services.7.2. Advertising.7.3. Solicitation of clients.7.4. Communication of fields of practice and specialization.7.5. Firm names and letterheads.7.6. Political contributions to obtain government legal engagements orappointments by judges.8.1. Bar admission and disciplinary matters.8.2. Judicial and legal officials.8.3. Reporting professional misconduct.8.4. Misconduct.8.5. Disciplinary authority; choice of law.FormsIndex follows Rules.Preamble: A lawyer’s responsibilities.[1] A lawyer, as a member of the legal profession, is a representative ofclients, an officer of the legal system and a public citizen having specialresponsibility for the quality of justice.[2] As a representative of clients, a lawyer performs various functions. Asadvisor, a lawyer provides a client with an informed understanding of the604

client’s legal rights and obligations and explains their practical implications.As advocate, a lawyer zealously asserts the client’s position under the rules ofthe adversary system. As negotiator, a lawyer seeks a result advantageous tothe client but consistent with requirements of honest dealings with others. Asan evaluator, a lawyer acts by examining a client’s legal affairs and reportingabout them to the client or to others.[3] In addition to these representational functions, a lawyer may serve as athird-party neutral, a nonrepresentational role helping the parties to resolve adispute or other matter. Some of these Rules apply directly to lawyers who areor have served as third-party neutrals. See, e.g., Rules 1.12 and 2.4. Inaddition, there are Rules that apply to lawyers who are not active in thepractice of law or to practicing lawyers even when they are acting in anonprofessional capacity. For example, a lawyer who commits fraud in theconduct of a business is subject to discipline for engaging in conduct involvingdishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation. See Rule 8.4.[4] In all professional functions a lawyer should be competent, prompt anddiligent. A lawyer should maintain communication with a client concerning therepresentation. A lawyer should keep in confidence information relating torepresentation of a client except so far as disclosure is required or permittedby the Rules of Professional Conduct or other law.[5] A lawyer’s conduct should conform to the requirements of the law, bothin professional service to clients and in the lawyer’s business and personalaffairs. A lawyer should use the law’s procedures only for legitimate purposesand not to harass or intimidate others. A lawyer should demonstrate respect forthe legal system and for those who serve it, including judges, other lawyersand public officials. While it is a lawyer’s duty, when necessary, to challengethe rectitude of official action, it is also a lawyer’s duty to uphold legalprocess.[6] As a public citizen, a lawyer should seek improvement of the law,access to the legal system, the administration of justice and the quality ofservice rendered by the legal profession. As a member of a learned profession,a lawyer should cultivate knowledge of the law beyond its use for clients,employ that knowledge in reform of the law and work to strengthen legaleducation. In addition, a lawyer should further the public’s understanding ofand confidence in the rule of law and the justice system because legal605

institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation andsupport to maintain their authority. A lawyer should be mindful of deficienciesin the administration of justice and of the fact that the poor, and sometimespersons who are not poor, cannot afford adequate legal assistance. Therefore,all lawyers should devote professional time and resources and use civicinfluence to ensure equal access to our system of justice for all those whobecause of economic or social barriers cannot afford or secure adequate legalcounsel. A lawyer should aid the legal profession in pursuing these objectivesand should help the bar regulate itself in the public interest.[7] Many of a lawyer’s professional responsibilities are prescribed in theRules of Professional Conduct, as well as substantive and procedural law.However, a lawyer is also guided by personal conscience and the approbationof professional peers. A lawyer should strive to attain the highest level of skill,to improve the law and the legal profession and to exemplify the legalprofession’s ideals of public service.[8] A lawyer’s responsibilities as a representative of clients, an officer ofthe legal system and a public citizen are usually harmonious. Thus, when anopposing party is well represented, a lawyer can be a zealous advocate onbehalf of a client and at the same time assume that justice is being done. Soalso, a lawyer can be sure that preserving client confidences ordinarily servesthe public interest because people are more likely to seek legal advice, andthereby heed their legal obligations, when they know their communicationswill be private.[9] In the nature of law practice, however, conflicting responsibilities areencountered. Virtually all difficult ethical problems arise from conflictbetween a lawyer’s responsibilities to clients, to the legal system and to thelawyer’s own interest in remaining an ethical person while earning asatisfactory living. The Rules of Professional conduct often prescribe terms forresolving such conflicts. Within the framework of these Rules, however, manydifficult issues of professional discretion can arise. Such issues must beresolved through the exercise of sensitive professional and moral judgmentguided by the basic principles underlying the Rules. These principles includethe lawyer’s obligation zealously to protect and pursue a client’s legitimateinterests, within the bounds of the law, while maintaining a professional,courteous and civil attitude toward all persons involved in the legal system.606

[10] The legal profession is largely self-governing. Although otherprofessions also have been granted powers of self-government, the legalprofession is unique in this respect because of the close relationship betweenthe profession and the processes of government and law enforcement. Thisconnection is manifested in the fact that ultimate authority over the legalprofession is vested largely in the courts.[11] To the extent that lawyers meet the obligations of their professionalcalling, the occasion for government regulation is obviated. Self-regulationalso helps maintain the legal profession’s independence from governmentdomination. An independent legal profession is an important force inpreserving government under law, for abuse of legal authority is more readilychallenged by a profession whose members are not dependent on governmentfor the right to practice.[12] The legal profession’s relative autonomy carries with it specialresponsibilities of self-government. The profession has a responsibility toassure that its regulations are conceived in the public interest and not infurtherance of parochial or self interested concerns of the bar. Every lawyer isresponsible for observance of the Rules of Professional Conduct. A lawyershould also aid in securing their observance by other lawyers. Neglect of theseresponsibilities compromises the independence of the profession and thepublic interest which it serves.[13] Lawyers play a vital role in the preservation of society. The fulfillmentof this role requires an understanding by lawyers of their relationship to ourlegal system. The Rules of Professional Conduct, when properly applied,serve to define that relationship.SCOPE[14] The Rules of Professional Conduct are rules of reason. They should beinterpreted with reference to the purposes of legal representation and of thelaw itself. Some of the Rules are imperatives, cast in the terms “shall” or“shall not.” These define proper conduct for purposes of professionaldiscipline. Others, generally cast in the term “may,” are permissive and defineareas under the Rules in which the lawyer has discretion to exerciseprofessional judgment. No disciplinary action should be taken when the lawyerchooses not to act or acts within the bounds of such discretion. Other Rulesdefine the nature of relationships between the lawyer and others. The Rules are607

thus partly obligatory and disciplinary and partly constitutive and descriptivein that they define a lawyer’s professional role. Many of the Comments use theterm “should.” Comments do not add obligations to the Rules but provideguidance for practicing in compliance with the Rules.[15] The Rules presuppose a larger legal context shaping the lawyer’s role.That context includes court rules and statutes relating to matters of licensure,laws defining specific obligations of lawyers and substantive and procedurallaw in general. The Comments are sometimes used to alert lawyers to theirresponsibilities under such other law.[16] Compliance with the Rules, as with all law in an open society, dependsprimarily upon understanding and voluntary compliance, secondarily uponreenforcement by peer and public opinion and finally, when necessary, uponenforcement through disciplinary proceedings. The Rules do not, however,exhaust the moral and ethical considerations that should inform a lawyer, forno worthwhile human activity can be completely defined by legal rules. TheRules simply provide a framework for the ethical practice of law.[17] Furthermore, for purposes of determining the lawyer’s authority andresponsibility, principles of substantive law external to these Rules determinewhether a client-lawyer relationship exists. Most of the duties flowing from theclient-lawyer relationship attach only after the client has requested the lawyerto render legal services and the lawyer has agreed to do so. But there are someduties, such as that of confidentiality under Rule 1.6, that attach when thelawyer agrees to consider whether a client-lawyer relationship shall beestablished. See Rule 1.18. Whether a client-lawyer relationship exists for anyspecific purpose can depend on the circumstances and may be a question offact.[18] Under various legal provisions, including constitutional, statutory andcommon law, the responsibilities of government lawyers may include authorityconcerning legal matters that ordinarily reposes in the client in private clientlawyer relationships. For example, a lawyer for a government agency mayhave authority on behalf of the government to decide upon settlement orwhether to appeal from an adverse judgment. Such authority in variousrespects is generally vested in the attorney general and the state’s attorney instate government, and their federal counterparts, and the same may be true ofother government law officers. Also, lawyers under the supervision of these608

officers may be authorized to represent several government agencies inintragovernmental legal controversies in circumstances where a private lawyercould not represent multiple private clients. These Rules do not abrogate anysuch authority.[19] Failure to comply with an obligation or prohibition imposed by a Ruleis a basis for invoking the disciplinary process. The Rules presuppose thatdisciplinary assessment of a lawyer’s conduct will be made on the basis of thefacts and circumstances as they existed at the time of the conduct in questionand in recognition of the fact that a lawyer often has to act upon uncertain orincomplete evidence of the situation. Moreover, the Rules presuppose thatwhether or not discipline should be imposed for a violation, and the severity ofa sanction, depend on all the circumstances, such as the willfulness andseriousness of the violation, extenuating factors and whether there have beenprevious violations.[20] Violation of a Rule should not itself give rise to a cause of actionagainst a lawyer nor should it create any presumption in such a case that alegal duty has been breached. In addition, violation of a Rule does notnecessarily warrant any other nondisciplinary remedy, such as disqualificationof a lawyer in pending litigation. The rules are designed to provide guidance tolawyers and to provide a structure for regulating conduct through disciplinaryagencies. They are not designed to be a basis for civil liability. Furthermore,the purpose of the Rules can be subverted when they are invoked by opposingparties as procedural weapons. The fact that a Rule is a just basis for alawyer’s self-assessment, or for sanctioning a lawyer under the administrationof a disciplinary authority, does not imply that an antagonist in a collateralproceeding or transaction has standing to seek enforcement of the Rule.[21] The Comment accompanying each Rule explains and illustrates themeaning and purpose of the Rule. The Preamble and this note on Scopeprovide general orientation. The Comments are intended as guides tointerpretation, but the text of each rule is authoritative.Rule 1.0. Terminology.(a) “Belief” or “believes” denotes that the person involved actuallysupposed the fact in question to be true. A person’s belief may be inferred fromcircumstances.609

(b) “Confirmed in writing,” when used in reference to the informed consentof a person, denotes informed consent that is given in writing by the person ora writing that a lawyer promptly transmits to the person confirming an oralinformed consent. See paragraph (e) for the definition of “informed consent.” Ifit is not feasible to obtain or transmit the writing at the time the person givesinformed consent, then the lawyer must obtain or transmit it within areasonable time thereafter.(c) “Firm” or “law firm” denotes a lawyer or lawyers in a law partnership,professional corporation, sole proprietorship or other association authorizedto practice law; or lawyers employed in a legal services organization or thelegal department of a corporation or other organization.(d) “Fraud” or “fraudulent” denotes conduct that is fraudulent under thesubstantive or procedural law of the applicable jurisdiction and has a purposeto deceive.(e) “Informed consent” denotes the agreement by a person to a proposedcourse of conduct after the lawyer has communicated adequate information andexplanation about the material risks of and reasonably available alternatives tothe proposed course of conduct.(f) “Knowingly,” “known,” or “knows” denotes actual knowledge of the factin question. A person’s knowledge may be inferred from circumstances.(g) “Partner” denotes a member of a partnership, a shareholder in a law firmorganized as a professional corporation, or a member of an associationauthorized to practice law.(h) “Reasonable” or “reasonably” when used in relation to conduct by alawyer denotes the conduct of a reasonably prudent and competent lawyer.(i) “Reasonable belief” or “reasonably believes” when used in reference toa lawyer denotes that the lawyer believes the matter in question and that thecircumstances are such that the belief is reasonable.(j) “Reasonably should know” when used in reference to a lawyer denotesthat a lawyer of reasonable prudence and competence would ascertain thematter in question.(k) “Screened” denotes the isolation of a lawyer from any participation in amatter through the timely imposition of procedures within a firm that are610

reasonably adequate under the circumstances to protect information that theisolated lawyer is obligated to protect under these Rules or other law.(l) “Substantial” when used in reference to degree or extent denotes amaterial matter of clear and weighty importance.(m) “Tribunal” denotes a court, an arbitrator in a binding arbitrationproceeding or a legislative body, administrative agency or other body acting inan adjudicative capacity. A legislative body, administrative agency or otherbody acts in an adjudicative capacity when a neutral official, after thepresentation of evidence or legal argument by a party or parties, will render abinding legal judgment directly affecting a party’s interests in a particularmatter.(n) “Writing” or “written” denotes a tangible or electronic record of acommunication or representation, including handwriting, typewriting, printing,photostating, photography, audio or video recording and electroniccommunications. A “signed” writing includes an electronic sound, symbol orprocess attached to or logically associated with a writing and executed oradopted by a person with the intent to sign the writing. (Amended, effectiveMar. 1, 2013.)COMMENT[1] Confirmed in Writing. — If it is not feasible to obtain or transmit awritten confirmation at the time the client gives informed consent, then thelawyer must obtain or transmit it within a reasonable time thereafter. If alawyer has obtained a client’s informed consent, the lawyer may act in relianceon that consent so long as it is confirmed in writing within a reasonable timethereafter.[2] Firm. — Whether two or more lawyers constitute a firm withinparagraph (c) can depend on the specific facts. For example, two practitionerswho share office space and occasionally consult or assist each other ordinarilywould not be regarded as constituting a firm. However, if they presentthemselves to the public in a way that suggests that they are a firm or conductthemselves as a firm, they should be regarded as a firm for purposes of theRules. The terms of any formal agreement between associated lawyers arerelevant in determining whether they are a firm, as is the fact that they havemutual access to information concerning the clients they serve. Furthermore, it611

is relevant in doubtful cases to consider the underlying purpose of the Rule thatis involved. A group of lawyers could be regarded as a firm for purposes ofthe Rule that the same lawyer should not represent opposing parties inlitigation, while it might not be so regarded for purposes of the Rule thatinformation acquired by one lawyer is attributed to another.[3] With respect to the law department of an organization, including thegovernment, there is ordinarily no question that the members of the departmentconstitute a firm within the meaning of the Rules of Professional Conduct.There can be uncertainty, however, as to the identity of the client. For example,it may not be clear whether the law department of a corporation represents asubsidiary or an affiliated corporation, as well as the corporation by which themembers of the department are directly employed. A similar question can ariseconcerning an unincorporated association and its local affiliates.[4] Similar questions can also arise with respect to lawyers in legal aid andlegal services organizations. Depending upon the structure of the organization,the entire organization or different components of it may constitute a firm orfirms for purposes of these Rules.[5] Fraud. — When used in these Rules, the terms “fraud” or “fraudulent”refer to conduct that is characterized as such under the substantive orprocedural law of the applicable jurisdiction and has a purpose to deceive.This does not include merely negligent misrepresentation or negligent failure toapprise another of relevant information. For purposes of these Rules, it is notnecessary that anyone has suffered damages or relied on the misrepresentationor failure to inform.[6] Informed Consent. — Many of the Rules of Professional Conductrequire the lawyer to obtain the informed consent of a client or other person(e.g., a former client or, under certain circumstances, a prospective client)before accepting or continuing representation or pursuing a course of conduct.See, e.g., Rules 1.2(c), 1.6(a) and 1.7(b). The communication necessary toobtain such consent will vary according to the Rule involved and thecircumstances giving rise to the need to obtain informed consent. The lawyermust make reasonable efforts to ensure that the client or other person possessesinformation reasonably adequate to make an informed decision. Ordinarily, thiswill require communication that includes a disclosure of the facts andcircumstances giving rise to the situation, any explanation reasonably612

necessary to inform the client or other person of the material advantages anddisadvantages of the proposed course of conduct and a discussion of theclient’s or other person’s options and alternatives. In some circumstances itmay be appropriate for a lawyer to advise a client or other person to seek theadvice of other counsel. A lawyer need not inform a client or other person offacts or implications already known to the client or other person; nevertheless,a lawyer who does not personally inform the client or other person assumes therisk that the client or other person is inadequately informed and the consent isinvalid. In determining whether the information and explanation provided arereasonably adequate, relevant factors include whether the client or otherperson is experienced in legal matters generally and in making decisions of thetype involved, and whether the client or other person is independentlyrepresented by other counsel in giving the consent. Normally, such personsneed less information and explanation than others, and generally a client orother person who is independently represented by other counsel in giving theconsent should be assumed to have given informed consent.[7] Obtaining informed consent will usually require an affirmative responseby the client or other person. In general, a lawyer may not assume consent froma client’s or other person’s silence. Consent may be inferred, however, fromthe conduct of a client or other person who has reasonably adequateinformation about the matter. A number of Rules require that a person’s consentbe confirmed in writing. See Rules 1.7(b) and 1.9(a). For a definition of“writing” and “confirmed in writing,” see paragraphs (n) and(b). Other Rulesrequire that a client’s consent be obtained in a writing signed by the client.See, e.g., Rules 1.8(a) and (g). For a definition of “signed,” see paragraph (n).[8] Screened. — This definition applies to situations where screening of apersonally disqualified lawyer is permitted to remove imputation of a conflictof interest under Rules 1.10, 1.11, 1.12 or 1.18.[9] The purpose of screening is to assure the affected parties thatconfidential information known by the personally disqualified lawyer remainsprotected. The personally disqualified lawyer should acknowledge theobligation not to communicate with any of the other lawyers in the firm withrespect to the matter. Similarly, other lawyers in the firm who are working onthe matter should be informed that the screening is in place and that they maynot communicate with the personally disqualified lawyer with respect to thematter. Additional screening measures that are appropriate for the particular613

matter will depend on the circumstances. To implement, reinforce and remindall affected lawyers of the presence of the screening, it may be appropriate forthe firm to undertake such procedures as a written undertaking by the screenedlawyer to avoid any communication with other firm personnel and any contactwith any firm files or other information, including information in electronicform, relating to the matter, written notice and instructions to all other firmpersonnel forbidding any communication with the screened lawyer relating tothe matter, denial of access by the screened lawyer to firm files or otherinformation, including information in electronic form, relating to the matter,and periodic reminders of the screen to the screened lawyer and all other firmpersonnel.[10] In order to be effective, screening measures must be implemented assoon as practical after a lawyer or law firm knows or reasonably should knowthat there is a need for screening.Cross references. — As to the Statement of Principles of Lawyer Conduct,see Supreme Court Rule 71(b)(ii).Effect of amendments. — The 2013 amendment, effective Mar. 1, 2013,substituted “electronic communications” for “email” in the first sentence in (n).NOTES TO DECISIONSKnowingly.Lawyer engaged in knowing misconduct, for which suspension was theappropriate discipline, by: (1) assisting a suspended lawyer in theunauthorized practice of law when the lawyer engaged the suspended lawyer towork on cases without determining the applicable restrictions; (2) failing tosupervise the suspended lawyer adequately; and (3) giving the suspendedlawyer a percentage of a contingency fee that included work performed bothbefore and after the suspension. In re Martin, — A.3d —, 2014 Del. LEXIS546 (Del. Nov. 18, 2014).Rule 1.1. Competence.A lawyer shall provide competent representation to a client. Competent614

representation requires the legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness andpreparation reasonably necessary for the representation.COMMENT[1] Legal knowledge and skill. — In determining whether a lawyer employsthe requisite knowledge and skill in a particular matter, relevant factorsinclude the relative complexity and specialized nature of the matter, thelawyer’s general experience, the lawyer’s training and experience in the fieldin question, the preparation and study the lawyer is able to give the matter andwhether it is feasible to refer the matter to, or associate or consult with, alawyer of established competence in the field in question. In many instances,the required proficiency is that of a general practitioner. Expertise in aparticular field of law may be required in some circumstances.[2] A lawyer need not necessarily have special training or prior experienceto handle legal problems of a type with which the lawyer is unfamiliar. Anewly admitted lawyer can be as competent as a practitioner with longexperience. Some important legal skills, such as the analysis of precedent, theevaluation of evidence and legal drafting, are required in all legal problems.Perhaps the most fundamental legal skill consists of determining what kind oflegal problems a situation may involve, a skill that necessarily transcends anyparticular specialized knowledge. A lawyer can provide adequaterepresentation in a wholly novel field through necessary study. Competentrepresentation can also be provided through the association of a lawyer ofestablished competence in the field in question.[3] In an emergency a lawyer may give advice or assistance in a matter inwhich the lawyer does not have the skill ordinarily required where referral toor consultation or association with another lawyer would be impractical. Evenin an emergency, however, assistance should be limited to that reasonablynecessary in the circumstances, for ill-considered action under emergencyconditions can jeopardize the client’s interest.[4] A lawyer may accept representation where the requisite level ofcompetence can be achieved by reasonable preparation. This applies as wellto a lawyer who is appointed as counsel for an unrepresented person. See alsoRule 6.2.[5] Thoroughness and preparation. — Competent handling of a particular615

matter includes inquiry into and analysis of the factual and legal elements ofthe problem, and use of methods and procedures meeting the standards ofcompetent practitioners. It also includes adequate preparation. The requiredattention and preparation are determined in part by what is at stake; majorlitigation and complex transactions ordinarily require more extensive treatmentthan matters of lesser complexity and consequence. An agreement between thelawyer and the client regarding the scope of the representation may limit thematters for which the lawyer is responsible. See Rule 1.2(c).[6] Retaining or contracting with other lawyers. — Before a lawyerretains or contracts with other lawyers outside the lawyer’s own firm toprovide or assist in the provision of legal services to a client, the lawyershould ordinarily obtain informed con

That context includes court rules and statutes relating to matters of licensure, laws defining specific obligations of lawyers and substantive and procedural law in general. The Comments are sometimes used to alert lawyers to their responsibilities under such other law. [16] Compliance with the Rules, as with all law in an open society, depends