Transcription

Dr. Larry Fong,Past President, College of Alberta Psychologists and Psychologists Association ofAlbertaThis book is an excellent resource compendium for practitioners workingwith children. It provides both theoretical constructs and best practicestrategies for engaging and intervening successfully with young people.I particularly liked the efforts that Dr. Chang and many of his contributorsmade towards sensitive engagement of children and their community ofsupporters.Don Andrews, M.Ed.,Director of Student Services, Independent School Advisory Committee, Calgary,AB, CanadaDr. Chang has compiled a major work, specifically organized to address anumber of essential questions in the treatment of children and their families. The book will help practitioners integrate theory and clinical practice.The contributors are highly knowledgeable and experienced professionals, who emphasize the importance of the relationship in understandingchildren and in the process of treatment. This is a timely, well-researchedvolume, theoretically sophisticated, yet practical in its clinical wisdom. Itcovers a range of problems with which children struggle.Dr. Don Pazaratz,President, Haydon Youth Services, Oshawa, ON, CanadaFamily Psychology PressCalgary9 780988 05960 3 Edited byJeff ChangISBN 978-0-9880596-0-3Creative Interventions with Children: A Transtheoretical ApproachDr. Chang has brought together experts in the field of children’s therapy,who not only have years of experience, but valuable insights into howchildren think, feel and respond to others. No doubt, this book will provide the readers with insights, based on the experience of many authors,which readers can use to improve their work with children.Creative Interventions with Children:A Transtheoretical ApproachEdited byJeff Chang

Creative Interventions withChildren: A TranstheoreticalApproachEdited byJeff ChangFamily Psychology PressCalgary

To the children we serve, and who teach us so much about work andlife, and to the parents who love them.Creative Interventions with Children: A Transtheoretical ApproachCopyright 2012 by Family Psychology PressAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or byany means without written permission from the author.ISBN: 978-0-9880596-0-3Printed in Canada

iThe EditorDr. Jeff Chang is Associate Professor in the Graduate Centre for Applied Psychology atAthabasca University, Director of The Family Psychology Centre, and Clinical Supervisor atCalgary Family Therapy Centre. He lives and works in Calgary, AB, Canada. He completed aPh.D. in Counselling Psychology at the University of Calgary, where his dissertation researchfocused on how Master’s students in counsellor education interpret their development. He hasbeen a Registered Psychologist in Alberta for twenty-five years, and is a Clinical Fellow andApproved Supervisor of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy.Dr. Chang has worked for over twenty-five years as a family therapist and psychologist,and supervisor/director, in children’s mental health, Employee Assistance Programs, andprivate practice. He has taught in graduate programs in family therapy and counsellingpsychology since 1989. He frequently supervises practicum students and licensure interns,directs children’s mental health programs, and maintains a private practice doing custodyevaluation and litigation support in family law matters.Dr. Chang presents and publishes on dialogic (narrative and solution-focused) therapies,family therapy, clinical supervision, and school-based mental health services. He has presentedin North America, Asia, and Europe.

iiThe ContributorsThe ContributorsStephen N. Baldridge, Ph.D., LMSW, Assistant Professor, BSSW Program Director, AbileneChristian University, Abilene, TX, USA.Kristin Boettger, RCAT, CCC, MA, Registered Art Therapist, Therapeutic Arts and HealingGardens Program, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB.Marielle A. Brandt, Ph.D, LPC, CPT, Professor, Department of Counselor Education,California State University, Sacramento, CA, USA.Diana K. Brown, M.A., LMFT, Clinical Counselor, Naval Station Everett, Fleet and FamilySupport Center, Marysville, WA.Felicia Carroll, M.Ed, M.A., LMFT, RPT-S, Adjunct Faculty, Pacifica Graduate Institute;Director, West Coast Institute for Gestalt Play Therapy, Solvang, CA, USA.Elysia Clemens, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO,USA.Rebecca A. Cobb, M.S., Doctoral Candidate, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL,USA.Mary Cole, M. Couns., CCC, Advisor, Disability Resource Centre, University of Calgary;private practice, Cole & Associates Counselling Services.Olena Darewych, M.A., RCAT, Faculty Member, Toronto Art Therapy Institute, Toronto, ON,Canada; President, Canadian Art Therapy Association.Erin M. Dugan, Ph.D., CRC, NCC, LPC-S, RPT-S, Assistant Professor, Louisiana StateUniversity Health Sciences Center - New Orleans, New Orleans, LA, USA.Sara E. Fey-Hinckley, M.A., LMFT, Mental Health Clinical Researcher, Department ofNeurosurgery, University of Washington/Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA.Wendy Froberg, Psy.D., R.Psych., IBECPT-P, CACPT-S, formerly Adjunct Assistant Professor,The University of Calgary; private practice, Calgary, AB, Canada.Ben Furman, M.D., Psychiatrist, Director, Helsinki Brief Therapy Institute, Helsinki, Finland.Greg Godard, M.Couns., R.Psych., Clinical Psychologist, Greg Godard PsychologicalServices, Medicine Hat, AB, Canada.Ruth Ogden Halstead, M.S., LMFTA, North Star Services, Crown Point, IN, USA.Chris Hammer, Ph.D., R.Psych., Silverhammer Coaching Services, Calgary, AB, Canada.Arden Henley, Ed.D., RCC, Dr. TCM (Hon), Principal of Canadian Programs, City Universityof Seattle; Director, Kean Henley Consultation, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

The ContributorsKelly Hesse, M.S., LMFT, Child Therapist, Operation Breakthrough, Inc., Kansas City, MO,USA.Jenny Orford Hill, ProfDocECAT, Reg Psychologist (private practice); Sessional Lecturer, LaTrobe University; Sessional Lecturer, Melbourne Institute for Experiential and CreativeArts Therapies, Melbourne, Australia.Maureen Howard, M.Sc., R.Psych., Mental Health Therapist, Alberta Health Services;psychologist, Maureen Howard & Associates, Pincher Creek, AB, Canada.Paul A. Jerry, M.A., R.Psych., Ph.D (Education), Associate Professor, Graduate Centre forApplied Psychology, Athabasca University, Medicine Hat, AB, Canada.Gunnur Karakurt, Ph.D., LMFT, Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University, Dept.of Family Medicine and Community Health, Cleveland, OH, USA.Kathleen B. Kmitta, M.S., LMFTA, Chesterton, IN, USA.Rachel Lewis, M.Sc., CFT, private practice, A Fresh Page, Montreal, QC, Canada.Liane MacDonald, M.Sc., R. Psych., Clinical Supervisor, Adolescent Day Treatment Program,Alberta Health Services; private practice, Imagine Psychological Services, Calgary, AB,CanadaMarilyn Magnuson, M.S.W., R.S.W., DVATI, RCAT, Express Yourself Child & Family ArtTherapy; Family Counsellor/Art Therapist, Adolescent Day Treatment Program, Calgary,AB, Canada.Jennifer L. Matheson, Ph.D., LMFT, Associate Professor, Colorado State University,Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Fort Collins, CO, USA.Jory McMillan, M.S.W., R.S.W., Mental Health Therapist, Alberta Health Services; SessionalInstructor, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.Einat S. Metzl, PhD, LMFT, ATR-BC, RYT, Assistant Professor, Loyola MarymountUniversity, School of Communications and Fine Arts, Dept. of Marital and Family Therapywith Specialization in Art Therapy, Los Angeles, CA, USA.Leslie Ann Moore, Ph.D., LMFT, Senior Lecturer, Counselor Education Program, TheUniversity of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA.Malissa Morrell, MA, LMFT, ATR-BC, Director of Expressive Arts, La Europa Academy,Salt Lake City, UT, USA.Evangeline Munns, Ph.D, C.Psych., RPT/S, CTT/ST, CACPTT/S, Munns PsychologicalConsultant Services, King City, ON, Canada.John J. Murphy, Ph.D, Licensed Psychologist, Professor, University of Central Arkansas,Conway, AR, USA.Sesen Negash, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Alliant University, San Diego, CA, USA.Jack Nowicki, LCSW, Senior Program Development Specialist, Texas Network of YouthServices & Lecturer at the University of Texas School of Social Work, Austin, TX, USA.R. Brett Nelson, Ph.D, NCSP, Licensed Psychologist and Credentialed School Psychologist;Professor and Coordinator, School Psychology Program, California State University, SanBernardino, CA, USA.Simon Nuttgens, Ph.D, R.Psych., Associate Professor, Graduate Centre for Applied Psychology,Athabasca University, Naramata, BC, Canada.David Nylund, Ph.D, LCSW, Professor, Department of Social Work, California State University,Sacramento, CA, USA.iii

ivThe ContributorsTina R. Paone, PhD, LPC, RPT-S, Associate Professor, Monmouth University, West LongBranch, NJ, USA.Karen Parsonson, Ph.D, Calgary, AB, Canada.Kenneth Phelps, Ph.D, LMFT, Assistant Clinical Professor and Outpatient Clinic Director,Department of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science, University of South CarolinaSchool of Medicine, Columbia, SC, USA.Shawn Powell, Ph.D, ABPP (School Psychology), Licensed Psychologist; Dean, School ofSocial & Behavioral Sciences, Casper College, Casper, WY, USA.Nathan Pyle, Ph.D, R.D.Psych., Psychologist, Child and Youth Mental Health and AddictionsServices, Prairie North Health Region, North Battleford, SK, Canada.Sabrina Ragan, M.Sc., CCC, CPT, R.Psych., Director, Keystone Child and Family Therapy,Grande Prairie, AB, Canada.Carrie J. Reid, M.A, RCAT, Owner, Mostly Salish Consulting, Qualicum Bay, BC, Canada.Carmen Richardson, M.S.W., R.S.W., RCAT, REAT, Director, Prairie Institute of ExpressiveArts Therapy, Calgary, AB, Canada.Nila Ricks, Ph.D., LMSW, Assistant Professor, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX, USA.Patricia N. E. Roberson., M.S., Doctoral Student, Child and Family Studies, the University ofTennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA.Laney Rosenzweig, M.S., LMFT, private practice, West Hartford, CT, USA; Visiting Faculty,University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.Adria Shipp, Ph.D, School Health Program Manager, Piedmont Health Services, Inc., Carrboro,NC, USA.Julie Tilsen, M.A., LP, Ph.D, Private Practice, Minneapolis, MN, USA.Risë VanFleet, Ph.D., RPT-S, CDBC, Founder and President, Family Enhancement & PlayTherapy Center, Inc. & The Playful Pooch Program, Boiling Springs, PA, USA.Lorie Walton, M.Ed, CPT-S, CTT-TS, Owner and lead therapist, Family First Play TherapyCentre Inc., Bradford, ON, Canada.David B. Ward, Ph.D., LMFT, Associate Professor and Department Chair, Marriage andFamily Therapy, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA, USA.Chloe Westelmajer, M.A., ATR, Clinical Coordinator of Residential Services, Wood’s Homes,Calgary, AB, Canada.Lorri Yasenik, MSW, RSW, CPT-S, RPT-S, Clinical Director, Rocky Mountain PsychologicalServices; Co-Owner, Rocky Mountain Play Therapy Institute, Calgary, AB, Canada.

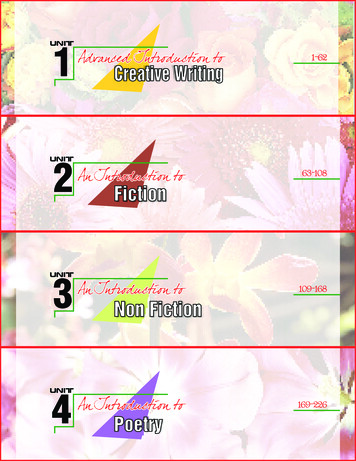

The ContributorsvTable of ContentsThe EditorThe ContributorsTable of ContentsiiivSection I: General Considerations in Children’s Therapy1 Introduction: Six Frames for Thinking about Therapy with Children and Their Families 32 The Necessity of Belonging and Other Discoveries12Section II: Creative Expressions: Art in Children’s Therapy3 Felting with Children4 Altered Book Making with Children5 Seeing Oneself Through Art6 Using Family Albums with Children of Divorce7 Outsider Witnessing Practices in Family Art Therapy8 Doll-Making9 The Colours of My Family Tree – Creative Genogram Mapping of Multi-GenerationalTrauma10 What I Look Like: Outside and Inside the Box11 My World of Feelings: Children Express Their Feelings, Problems, Strengths, andSolutions232935404450566266Section III: Changing Experience, Thought, and Action12 Kids’ Skills: A Solution-Focused Protocol for Helping Children Overcome Problems byLearning Skills7513 Naming and Taming Beasts: Extending the Narrative Metaphor8114 Using a Coach Approach with Children8615 Movie Magic: Building Solutions from the Client’s “Greatest Hits”9116 The Boffey Map: A Cognitive Behavioral Intervention9717 Curing Parental “Fears and Worries”: A Novel Approach to Decreasing TroublesomeChild Behaviours10218 Compliance Training According to Skinner’s Theory of Applied Behavior10619 Getting a Game Plan: Increasing Structure and Treatment Focus11020 Barbies and Beer: Narrative Therapy with a Gender Variant Child11521 A Hero’s Journey: Helping Children Re-Tell Their Problem Stories12022 The Narrative Construction of One Boy’s Real World12523 Hypnosis/Trance-work with Children13124 The Time-Away Corner13625 The Big Feelings Genogram14226 The ‘Internalized Other’ Interview with Children and Families14727 Treating Separation Anxiety Using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy15328 Friendly Ghosts: Re-Membering Conversations with Children15829 Scaling with Circles16330 Accelerated Resolution Therapy with Children167Section IV: The Healing Power of Play31 Child-Centered Play Therapy32 The Holding Environment in Child Therapy173181

viThe Contributors33 Every Child’s Life Is Worth A Story: A Tool For Integration34 Creating an Internal Locus of Control for Children through Returning Responsibility35 “Holding It Together”: Metaphors of Containment in Play Therapy36 Setting the Scene: A Multi-modal Approach to Tackling Multiple Problems in Families37 Caring for Hurts: A Theraplay Activity38 The Magic of Touch with a Cotton Ball39 Using Scenotest with Children of High Conflict Separation and Divorce40 Description as an Intervention When Working Therapeutically With Children187192197204210214220226Section V: Best Friends: Animal Assisted Techniques Therapy41 Canine-Assisted Play Therapy: Harnessing the Power of Cross-Species Play42 Has Therapy Gone To The Dogs?233240Section VI: Therapeutic Games43 Therapeutic Board Games with Latency-Aged Children44 Whose Job Is It? A Game About Responsibility45 Personal Power Cards: A Game for Oppositional Children249254260Section VII: Peer Power: Groups46 Structured Freedom in Group Art Therapy47 Group Activity Therapy48 Creative Empowerment for Girls: Strengthening Her Awakening Voice267273279

1Section IGeneral Considerations inChildren’s Therapy

2

Introduction31Introduction: Six Frames for Thinking aboutTherapy with Children and Their FamiliesJeff ChangI am delighted to have edited this volume of wonderfully creative interventions inchildren’s therapy. I am so very proud of all the authors who have contributed. Some are“old hands” at writing for publication, with many articles and books to their credit, whileothers are new practitioners who have long careers ahead of them, and whose innovations willinvigorate the field. This book is exciting to me because it emulates how most child and familytherapists work – they create and “steal” ideas from others, and integrate these ideas into theirwork. Most therapists I know maintain some kind of theoretical coherence, neither diggingtheir heels into theoretical rigidity, nor degenerating into a chaotic mishmash of therapeutictechniques. The best maintain a balance of creativity and conceptual rigor.The rich collection of tools in this volume has inspired me to clarify some frameworksthat have helped me to conceptualize this enterprise of therapy with children. The “success”or “failure” of the interventions in this collection does not stand on the particular interventionitself, but instead relies on the preparation and thoughtfulness exercised by each of thecontributing authors. Each contributor rests his or her intervention on a coherent philosophicalor theoretical stance, while considering the context in which the therapy is delivered. If Imay be forgiven for using a combat metaphor, the interventions each of the contributorsdescribes are “the tip of the spear.” They describe the “micro” of therapy. While the purposeof this book is to present creative ideas, and while I have asked the chapter authors to connecttheir interventions to some theoretical moorings, I would be remiss if I did not specify someframeworks for practice that provide a bit of context for the conduct of children’s therapy.There are almost as many theoretical approaches to child therapy as there are childtherapists. As the title of this book suggests, the reality of therapy on the front lines is thatpractitioners borrow from many theoretical traditions. However, in my view, it is necessaryto think more broadly about how we position ourselves when doing child and family therapy.Here are a few habits of thought I have learned along the way.Think Discursively and DeconstructivelyI think it is useful to see the “big ideas” that operate in our culture, so that we canunderstand their origin and development. By and large, big ideas or discourses are taken forgranted by most people in our culture. We are often so close to them that we cannot see howdiscourses stand behind and sponsor our ideas and beliefs – we often cannot see the forest forthe trees. These dominant discourses include: the preference for knowing through modernist,scientific thought; ideas about how women and men differ; ideas about “normal” sexuality;preference for learning via verbal/linguistic means; and the nature of childhood.

4IntroductionI think it is also useful to distinguish the “not-so-big” ideas that influence children andfamilies in more local ways. They rest on the big ideas. For instance, the “not so big” idea thata child should achieve “up to his potential” in school rests on the larger idea that society iskinder to those who have a typical education. So too, the concept that children can be classifiedas “ADHD” or “learning disabled” rests on the primacy of scientific thinking and diagnosticclassification.Discourses are not neutral; they are not just ideas. Foucault focused on how discoursesspecify and shape human life and behavior (Horrocks & Jevtic, 1997). Discourses spell outhow people should be in several arenas. Foucault refers to the education, health care, andlegal systems, and religious institutions as “surfaces of emergence.” They exercise influence,if not control, by perpetuating ideas of what is good enough or normal. Coming from asocial constructionist angle, Gergen (1991) proposes that many of the descriptors used torepresent the “self,” (“low self-esteem,” “authoritarian,” “externally controlled,” “repressed,”“depressed,” etc., to name just five of the twenty-two examples he listed) have only been incommon use since the twentieth century: “[T]he vocabulary of human deficit has undergoneenormous expansion within the past century. We have countless ways of locating faults thatwere unavailable even to our great-grandfathers” (pp. 13-14). This “vocabulary of deficit”has spread from professionals to the public at large, who come to see themselves and othersin terms of a disorder or diagnostic category. In my view, as therapists, we ought to examinethe historical and cultural context in which our theories of therapy arose. By examining ordeconstructing discourses, we can see how they invite us to behave, how they suggest that wetreat people, and the implications of our actions as therapists.However, clinical practice with children and families is not a philosophy seminar. Parentsbring in their troubled and troubling children, many of whom have great difficulty managingthe demands of everyday life. Accordingly, in clinical practice, I usually start with the family’sview of problems, since families usually experience more respect and acknowledgment whenwe discuss the problems that are important to them, rather than esoteric philosophical ideas.Being aware of discourses provides context to help me understand what I am doing, and keepsme aware of the social constructions that support the problem.I want to make it clear that I am not suggesting that diagnosis is futile. It provides acommon language that can be useful to communicate with other professionals, qualifychildren to receive services in a time of scarce resources, and to plan treatment. Moreover,the value of a diagnosis, like any other conceptualization or explanation, is in its utility, not inits “truth” (Amundson, 1996). Diagnoses earn their keep by providing useful ideas to guidetreatment, opening space for new options, and providing context. A diagnosis can tell usabout the common elements of a problem, which is useful as long as clients’ experience isnot subordinated to the diagnosis. For example, a diagnosis of Attention Deficit HyperactivityDisorder (ADHD) relies on some common defining characteristics. Nonetheless, one person’sexperience of ADHD may be very different from another’s. Diagnoses can also open spacefor new responses. A diagnosis could define a child not as “crazy” or “bad,” but as havingunusual ways of learning, or novel approaches to responding to challenges. Seeing the problemdifferently can point us toward different pathways to intervene. It is useful, however, to keepin the back of our minds that our diagnostic schemas and theoretical models emerge froma particular historical and cultural moment (Spiegel, 2005). They provide but one way ofconceptualizing human problems (Strong, 2012).As you read the chapters in this book, keep in mind the larger cultural stories that standbehind your therapeutic thinking, and the beliefs and explanations that our clients hold. Permityour curiosity to inhabit you, and, if possible, reflect on how you relate to the discourses thathold sway in your clinical setting.

IntroductionThink CoherentlyHere, I do not mean to suggest that you, the reader, does not already think coherently.I am simply acknowledging that this volume samples techniques from across the range oftheoretical orientations. I hope readers come from diverse theoretical stances, as well. Whateveryour theoretical orientation, I assert that child therapists should develop a clear theoreticalorientation that fits for them personally. The literature on common factors (Duncan, Miller,& Sparks, 2004; Duncan, 2010) indicates that, while no theoretical approach to therapy issuperior to any other, having a clearly developed theoretical stance helps therapists to orientthemselves, explain to themselves and others what they are doing and why they are doing it,and to move confidently in planning and executing their therapeutic interventions – so-calledallegiance effects.Norcross (2005) identified four approaches to psychotherapy integration: technicaleclecticism, theoretical integration, common factors approach, and assimilative integration. Intechnical eclecticism, practitioners combine techniques, while focusing on what interventionsare most effective with particular problems or populations, without necessarily subscribing tothe theories from which they arose. In theoretical integration, practitioners emphasize boththe integration of two or more underlying theories, and the integration of techniques. Theintegrated theory is more than the sum of its parts, and can give rise to new directions forpractice and research. The common factors approach asks what core elements are shared byeffective therapies, and seeks to potentiate these factors to create effective treatments. Finally,assimilative integrationists practice from one primary model, and introduce techniques fromother models, subordinated to their primary theoretical orientation.As you use this book, I urge you to sharpen and clarify your theoretical orientation and yourapproach to integration. Then I urge to you to purposefully integrate the creative techniquesyou will find here into a coherent theoretical framework – your theoretical framework. Engagein the intellectual struggle to make it clear to yourself what you are doing as a therapist, andwhy you are doing it.Think RelationallyThe therapeutic relationship is the most potent contributor to therapeutic outcome (Miller,Duncan, Brown, Sorrell, & Chalk, 2006). Asking for feedback about the alliance improvesoutcome. Accordingly, it is important to track the strength and viability of your alliance withthe client system – that is, not simply the child, but with the parents, extended family, schoolpersonnel, and many others.It is also important to get the relationship off on the right foot. Imagine being at yourgraduate school office. You receive a phone call telling you to meet with your committeein two hours. When you ask the reason you are to meet, it is vague. Dutifully you go. Theothers, all senior to you, are already there. As you enter, you are informed that you are tohave a comprehensive oral examination on research methods. now. How would you react?Would you be anxious? Angry? Would cooperation come easily to you? This might mirrorthe experience of a child entering therapy, and I would be tempted to ask why anyone wouldcooperate with such a procedure.Imagine for a moment another scenario. As a preteen, who was the person you alwayslooked forward to seeing? Maybe it was an older sibling’s boyfriend or girlfriend, an aunt oruncle, grandparent, family friend, coach, Cub or Scout leader, or teacher. What was significantabout that person? If you are anything like me, it was not very complicated: the person listenedto you, was more fun and interesting than your parents, and seemed like (s)he really wanted tospend time with you. We are responsible for initiating relationships that can support our youngclients’ desire to experiment with different behaviors. Solution-focused ideas about relationship(De Jong & Berg, 2013) suggest that we fit our recommendations for client action with their5

6Introductionrelationship to our services. In the context of a lack of familiarity, anxiety, and perhaps feeling“I am a bad kid”, children generally do not come with a customer style relationship. It’s ourresponsibility to ensure that our invitations to relationship are actually inviting, and to ensurethat we are hospitably hosting therapeutic conversations (Furman & Ahola, 1992).To get the relationship off on the right foot, I work to place myself in the position of atherapeutic uncle. If the child is in the waiting room with a parent, I make sure that I spendtime on the floor, meeting the child there before inviting the family into my office. I engage insmall talk about interests, schools (and getting out of school to see me), siblings, and the like.My style is a bit boisterous and silly at times, and I typically use that to my advantage by actingplayfully, all this before I ever get into my office.Use your natural style to connect with the children who come to see you; use what worksfor you. Be someone they enjoy coming to see; be one of the rare people in their lives who isnot interested in telling them what to do – just be present. Remind yourself that it is not theinterventions, in and of themselves, that are healing, but the intervention in the context ofyour therapeutic alliance. If the creative ideas we feature in this book don’t seem to “work,”consider how you can adjust your approach to your young client to strengthen the alliance.Think DevelopmentallyWhile some postmodern colleagues have eschewed a normalizing discourse (e.g., Madigan& Epston, 1995), I believe that such ideas – for example, Erikson’s (1950) psychosocialdevelopment stages or Piaget’s (1977) cognitive development stages – can be useful if they donot overwhelm the knowledge and experience of our clients. Moreover, there is a rich socialconstructionist literature on child development (e.g., Bruner, 1987; Bryant, 1979; Butterworth,1987; Feldman, 1987; Lloyd, 1987; Smedslund, 1979) that is critical of fixed notions of childdevelopment and the fixed ways in which they invite us to act, but acknowledge how childrendevelop as they grow older.Cognitive DevelopmentMemory researchers and specialists in cognitive and language development generallyassert that elementary aged children have richer experiences of events in their lives than theycan typically express verbally (Fivush, Kuebli, & Clubb, 1992; Price and Goodman, 1990;Nelson, 1986). In conversations with adults, children are quite sensitive to their conversationalpartners, and begin to anticipate their listeners’ needs. They engage in metacognition, thatis, they evaluate what they are saying and check that it fits with the purpose and context ofconversation.Children between the ages of six and eleven have typically developed the ability tode-center, that is, to construe events from others’ points of view. They can create mentalrepresentations of a series of concrete actions, usually events that they have alreadyexperienced. It is much more difficult for children this age to create mental representations ofabstractions, but it is helpful if concrete objects or visual representations are used to aid thecreation of representations. Inductive reasoning – generalizing from specific instance to infera general theory – is generally mastered by children this age. On the other hand, before twelveor thirteen, young people have great difficulty reversing this process – beginning with a theoryor principle and predicting what should occur (Bryant, 1979).It is generally agreed that, before the age of ten or eleven, children do not store memoriesas sequential narratives. What is stored in memory tends to be very accurate, specific, anddiscrete, and can be organized into therapeutically useful experiences by repeated telling(Bull, 1995; Fivush & Shukat, 1995; Poole & White, 1995; Saywitz, 1995).Erik Erikson (1950) suggested that school aged children have a need to exercise masteryover the world -- what he termed the struggle of “industry versus inferiority.” While stage

Introductiontheories of normal development have been criticized from a postmodern or narrative perspective(e.g., Sanders, 1997), experientially, Erikson’s assertion rings true to me. Children between theages of about six and eleven love to influence the world and they love to note their impact andmastery on it. My

Athabasca University, Director of The Family Psychology Centre, and Clinical Supervisor at Calgary Family Therapy Centre. He lives and works in Calgary, AB, Canada. He completed a Ph.D. in Counselling Psychology at the University of Calgary, where his dissertation research