Transcription

D17-38607June 2018Best practice primary andsecondary preventativeinterventions in chronic diseasein remote AustraliaBarbara Schmidt, Janie Dade Smith and Kristine Battye from the Barbara Schmidt &Associates PTT LTD, Manunda, Queensland, have prepared this report on behalf ofthe Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

Published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health CareLevel 5, 255 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000Phone: (02) 9126 3600Fax: (02) 9126 3613Email: mail@safetyandquality.gov.auWebsite: www.safetyandquality.gov.auISBN: 978-1-925665-49-9 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2017All material and work produced by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality inHealth Care (the Commission) is protected by copyright. The Commission reserves the rightto set out the terms and conditions for the use of such material.As far as practicable, material for which the copyright is owned by a third party will be clearlylabelled. The Commission has made all reasonable efforts to ensure that this material hasbeen reproduced in this publication with the full consent of the copyright owners.With the exception of any material protected by a trademark, any content provided by thirdparties and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this publication is licensedunder a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivatives 4.0 Internationallicence.Enquiries about the licence and any use of this publication are welcome and can be sent tocommunications@safetyandquality.gov.au.The Commission’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourcedfrom it) using the following citation:Schmidt B, Smith D J, Battye K. Strategies for implementing best practice primaryand secondary preventative interventions in chronic disease in remote Australia.Sydney: ACSQHC; 2017DisclaimerThe content of this document is published in good faith by the Commission for informationpurposes. The document is not intended to provide guidance on particular healthcarechoices. You should contact your health care provider for information or advice on particularhealthcare choices.This document includes the views or recommendations of its authors and third parties.Publication of this document by the Commission does not necessarily reflect the views of theCommission, or indicate a commitment to a particular course of action. The Commissiondoes not accept any legal liability for any injury, loss or damage incurred by the use of, orreliance on, this document.Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventionsII

PrefaceThe Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (the Commission)publishes the Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation series with the aim of improving theappropriateness of health care in Australia.In November 2015, the Commission published the first Australian Atlas of HealthcareVariation (the Atlas). The Atlas made 67 recommendations for reducing unwarrantedvariation and promoting appropriate care. In May 2016 the Australian Health Ministers’Advisory Council (AHMAC) noted the implementation strategy addressing the Atlasrecommendations.The Atlas showed that people living in remote Australia have a much higher prevalence ofchronic disease and significant variation in interventions delivered when compared withpeople living in cities. Recommendation 6a stated that the Commission host a roundtable ofservice provider and consumer groups from remote areas to identify successful strategies forimplementing best practice primary and secondary prevention services for patients withchronic disease in remote Australia. The Commission expanded the scope of thisrecommendation and included a review of Australian literature and interviews with keyprogram leaders.In March 2017, the Commission contracted Barbara Schmidt and Associates to identify anddescribe best practice primary and secondary prevention services for patients with chronicdisease in remote Australia. This preface, which is written by the Commission, provides anoverview of the project. Barbara Schmidt and Associates wrote the remainder of the report.The Commission worked closely with the authors and thanks Barbara Schmidt andAssociates for its commitment to the project. The report offers insights for healthcareprofessionals about best practice primary and secondary prevention services for patientswith chronic disease in remote Australia. The report provides: A literature overview of Australian research in primary and secondarypreventative interventions in chronic disease in remote Australia A description of successful strategies being implemented, the potentialeffectiveness and impact of these initiatives Examples of best practices in primary and secondary preventative interventionsin chronic disease implemented in remote Australia A summary of enablers and barriers in implementing best practice primary andsecondary preventative interventions in chronic disease in remote Australia.The report found that the key enabler for successful and sustainable primary preventionprograms is leadership by a community organisation. The common success factor forsecondary prevention intervention is that the health service has made the paradigm shift tothe chronic care model to guide service planning, underpinned by a continuous qualityimprovement framework. Each of the examples showcase an intervention that improvedservice access by strengthening at least one of the health service domains of the chroniccare model.The Commission continues its program of work focused on improving the appropriateness ofhealth care in Australia.Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventionsIII

ContentsPreface .IIIAbbreviations . 1Summary . 3Introduction. 61.1.1The remote context1.1.1 Remote Health Service Delivery Models1.1.2 Health Providers in Remote Australia1.1.3 Retaining the workforce1.26777Public policy and health – the clinical context1.2.1 Chronic disease model of care1.2.2 Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in remote Australia889Project aim, scope and methodology. 102.2.1Project Scope102.2Methodology11Literature overview . 123.3.1Primary prevention for chronic , adult and older person’s health checksHealth information systemsImmunisationHealthy lifestyle programsSmokingNutritionPhysical activity3.2 Secondary Prevention for Specific Chronic Conditions3.2.1 Chronic disease guidelines and care planning3.2.2 Diabetes and Amputations3.2.3 Cardiovascular disease and respiratory disease121212121313131414141415Findings Best practice interventions . 174.4.1Roundtable discussion174.2Primary prevention interventions184.2.1 Nutrition and the Food Ladder - Ramingining4.2.2 Be Healthy and Safe Maranoa Project4.3Secondary prevention interventions1818194.3.1 Service Delivery Design194.3.1.1 Decentralised Service Delivery Model – Congress4.3.1.2 Outreach Generalist Physician Model – Katherine Hospital4.3.1.3 Telehealth outreach services for diabetic retinopathy4.3.2 Clinical Decision Support Systems4.3.2.1 Patient information system management - Kimberley Aboriginal MedicalService4.3.2.2 Clinical Decisions making tools – Top End Health Service4.3.2.3 Quality improvement using MedicineInsight – Tasmania GP202122Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventions22232324IV

4.3.3 Organisational influence and integration4.3.3.1 Regional program support systems – Nganampa Health4.2.3.2 Health system organisation and integration - Maari MaEnablers and barriers to best practice . 275.5.1Enablers to best practice interventions5.1.1 Improving primary prevention interventions5.1.2 Improving secondary prevention interventions5.26.242525Barriers to best practice and improved chronic disease outcomes27272830Summary . 31Appendix 1: Methodology . 32Step 1: Literature review discussion paper32Step 2: Roundtable meeting33Step 3: Consultation process33Step 4: Collation and analysis34Step 5: Production of the project report34Appendix 2: Stakeholders consulted . 35Appendix 3: Interview questions . 37Appendix 4: Case exemplars . 38References . 53Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventionsV

AbbreviationsACCHOAboriginal Community Controlled Health OrganisationACCHSAboriginal Community Controlled Health ServiceAHPAboriginal Health PractitionerAIHWAustralian Institute of Health and WelfareALPAArnhem Land Progress Aboriginal CorporationAMSAboriginal Medical ServiceAPYAnangu Pitjantjatjara YankunytjatjaraBRAMSBroome Regional Aboriginal Medical ServiceCAACCentral Australian Aboriginal CongressCCMMChronic Conditions Management ModelCDChronic DiseaseCDUCharles Darwin UniversityCOPDChronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseCWHHSCentral West Hospital and Health ServiceDRDiabetic RetinopathyGPGeneral PractitionerGPMPGeneral Practice Management PlanHbA1CHaemoglobin A1C – a blood test that indicates blood glucose is controlICOPIndigenous Cardiac Outreach ProgramIHPIndigenous Health PractitionerIHWIndigenous Health WorkerKAMSKimberley Aboriginal Medical ServiceKWHBKatherine West Health BoardLHNLocal Health NetworkMBSMedical Benefits SchemeMMExThis is the name of the patient information system marketed by IPAHealthcareBest practice primary and secondary preventative interventions1

MoUMemorandum of UnderstandingNGONon-Government OrganisationNHMRCNational Health and Medical Research CouncilNHCNganampa Health CouncilNTNorthern TerritoryPBSPharmaceutical Benefits SchemePCISPrimary Care Information SystemPHCPrimary Health CarePHNPrimary Health NetworkPISPatient Information SystemRACGPRoyal Australian College of General PractitionersRANZCORoyal Australian and New Zealand College of OphthalmologistsRHDRheumatic Heart DiseaseRFDSRoyal Flying Doctor ServiceRNRegistered NurseRODRSSRemote Outreach Diabetic Retinopathy Screening ServiceSWHHSSouth West Hospital and Health ServiceTEHSTop End Health ServiceBest practice primary and secondary preventative interventions2

SummaryPeople living in remote Australia have a much higher prevalence of chronic disease andsignificant variation in interventions delivered when compared with urban dwellers. Theselargely include variations in medicines for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseand Alzheimer’s disease and significant variations in hospital admission rates for heartfailure and diabetes related lower limb amputations.In March 2017 the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care contractedBarbara Schmidt and Associates to undertake a consultancy to identify and describesuccessful strategies that effectively implement best practice primary and secondaryprevention services for patients with chronic disease in remote Australia. The methodologyconsisted of a literature overview, consultation with key stakeholders in remote Australia,collation and analysis of materials and a written report.The literature overview identified a number of successful interventions for effective primaryprevention of chronic disease. These include existing child, adult and older person’s healthchecks, immunisation programs, and healthy lifestyle programs for smoking, nutrition andphysical activity. Best practice secondary prevention initiatives were also identified in theliterature, these include several best practice clinical chronic disease guidelines and careplanning instruments for chronic disease management in remote areas; studies into diabetesmanagement specifically the Getting Better at Chronic Care project in north Queensland, theABCDE Project in the Northern Territory, and the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical ServiceRetinal Screening Program.1-3 While a number of other initiatives were also identified, thereis limited published literature on successful initiatives, and many of those identified are nolonger delivered in remote communities. This may be due to common issues found in remoteAustralia such as the initiative being a pilot program, defunding of the initiative, the personwho championed it has left, or the program outcomes have not been published.The consultation process consisted of a roundtable discussion forum (n 12) held in Cairnswith the participants from the National Rural Health Conference, and a remote consultationprocess (n 15) across five states. The roundtable assisted in identifying several bestpractice examples of primary and secondary prevention services in remote Australia, and inidentifying key stakeholders for the interviewing process. The conference presentations werealso targeted to identify new initiatives in primary and secondary prevention in remoteAustralia.The consultation findings revealed that to be successful, any initiative must reflect featuresof the Chronic Care Model.4 Successful primary prevention strategies had the followingfeatures: collaboration with several community based agencies usually external to the healthservices; a partnership approach; and a focus on the social determinants of health. Thesefeatures contribute to the sustainability of initiatives. Two successful primary preventioninitiatives were reported to demonstrate these characteristics. The first is the Food Ladder, afood security and social business model operating in Ramingining and Katherine in theNorthern Territory. In the first six months of operation in Ramingining a 5% increase in thesale and consumption of fruit and vegetables was reported. The second is a successfulhealth promotion model, the Be Heathy and Safe Maranoa Project from Roma inQueensland, where the regional council is the first stop and coordinator for all healthpromotion initiatives in the shire.Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventions3

Three successful and well embedded secondary prevention models were identified in theconsultation process that demonstrate how a change in service delivery design can improveaccess to services to manage chronic disease:1. The Central Australian Aboriginal Congress in the Northern Territory – adecentralised model of care based on population numbers, better use ofinfrastructure, and a redefinition of service delivery roles improved screening andcare planning.2. A Generalist Physician Outreach Model in Katherine in the Northern Territory – ageneral physician model of specialist service delivery integrated into primary healthcare service delivery improved continuity of care.3. A Telehealth model in central Western Queensland – provides access to specialistservices for people living in remote areas to avoid patient travel, improve appropriatescreening, prevent hospitalisations and manage a chronic condition using bestpractice guidelines.Best practice clinical decision support includes electronic patient records, practicemanagement, care planning and recall systems, medication management, and securereferral processes. The project identified a number of examples of the use of a systematicapproach to chronic care:1. The Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service uses MMex as their corporate system for anetwork of eight community controlled health services in Western Australia.2. Top End Health Service in the Northern Territory uses the Chronic ConditionsManagement Model as a systematic and integrated approach to prevent and managechronic disease by streamlining systems to improve coordination, integration,delivery, documentation and evaluation of care. Over four years these changes haveled to almost a doubling in care planning for patients to 61%, with nearly 96% ofdiabetic patients having had a HbA1C recorded in the past year as well as areduction in preventable hospitalisations.3. MedicineInsight is used in rural Tasmania to promote quality improvement inprescribing, whereby GPs can compare their prescribing with other GPs at local,regional and national levels.4. Nganampa Health Service in Central Australia found that having a dedicated chronicdisease program manager who provides ongoing professional development for staffand measures compliance with clinical protocols for chronic disease prevention, hascontributed to a reduction in emergency evacuations by 57% in the past year.5. Maari Ma Health Service Aboriginal Corporation in Broken Hill uses a hub and spokemodel to deliver a comprehensive coordinated primary care strategy in the Far WestRegion of New South Wales. The key features of the strategy include client focuseddelivery of care quality improvement and population health approach to address riskfactors across the continuum. In the past five years this has resulted in a ten-foldincrease in screening, almost 80% of clients having a care plan and there arereported improvements in blood pressure control.The overarching finding of this study is that a systematic approach to chronic diseaseprevention and management is critical for success. The main enablers for success toimprove primary prevention are to ensure:Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventions4

That any intervention is embedded into the social fabric of the community Strong partnerships are developed to empower the community, recognising that theseare often found outside the health sector Interventions are tailored specifically to each remote community Screening is targeted for different age and gender groups Sustainable long term funding to support initiatives that build on the socialdeterminants of health.To improve secondary prevention interventions the enablers are to: Use a system approach to chronic disease care Redesign health services to implement the chronic care model Embed continuous quality improvement into the culture of service planning, monitoringand evaluation to ensure chronic disease is ‘everyone’s business’.This will involve having a clear blueprint for service development, actively engaging withclinicians, investing in training and supporting the workforce, having and ensuring allpractitioners use the same clinical information and decision support system, proactivelysupporting telehealth and ensuring all initiatives and staff understand the construct of thecommunity in which they serve.Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventions5

1. IntroductionPeople living in remote parts of Australia have higher rates of chronic disease thanpeople living in urban and regional areas.5-7 The percentage of the population whosmoke, drink to excess, are obese and are physically inactive is also higher.8 Hospitaladmission rates for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), andheart failure are markedly higher in remote areas and highest in low socioeconomicstatus groups. Death rates for diabetes is three times those living in urban areas anddeath rates for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease andasthma are all significantly higher.5,6,9The first Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation (the Atlas), released in November2015, identified variation in interventions delivered for a number of chronic conditionsbetween remote, regional and urban areas.5 These included dispensing of medicinesfor asthma and COPD, and anticholinesterase medicine used to treat Alzheimer’sdisease, hospital admission rates following heart failure, diabetes related low limbamputation and average length of stay in hospital for people with stroke. Dispensingof medicines for asthma showed a strong socioeconomic trend, with dispensing rateshighest in the lowest socioeconomic groups, highest in major cities and lowest inremote areas.5 Rates of diabetes-related lower limb amputations are higher in remoteareas compared to metropolitan areas. Indigenous people in remote areas are aboutthree times more likely to have diabetes, 10 times more likely to be admitted fordiabetic foot complications and 30 times more likely to suffer diabetes-related lowerlimb amputation than non-Indigenous people.5 There is considerable variation in thedispensing of anticholinesterase medicines, used to alleviate symptoms of somedementia types. Dispensing rates were higher in major cities than in regional andremote areas.5There are distinct features of remote populations that contribute to the variation ininterventions to address chronic disease. These include the remote health context,the models of service delivery, many different health service providers, and workforcerecruitment and retention. Public health policy, and the approach to service deliverythat underpins how chronic diseases are managed in remote areas, also influencethe variation in health outcomes.1.1 The remote contextRemote Australia makes up 78 per cent of the landmass of Australia. It is enormouslydiverse geographically, climatically, culturally as well as clinically for those healthprofessionals working there.Remote populations are geographically dispersed, with many small communitiesspread over large distances. This means there is not the critical mass of populationto have the full range of primary health care services in every community to preventand manage chronic disease. In addition to being geographically remote, peopleliving in remote areas are generally of lower socioeconomic status and there is ahigher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have complexhealth care needs.10,11 These geographic factors and underlying social determinantsof health all contribute to this variation in health status and service utilisation inremote areas.There are also significant differences between remote and very remote practicebecause of the distance involved in accessing health care, the types of healthBest practice primary and secondary preventative interventions6

professionals available, support available for clinicians, the cross-cultural nature ofthe work and the types of populations being serviced.12 It is this remote context thatchanges everything about a normal situation and requires health professionals towork from different remote models of care that usually don’t include hospitals,general practices and doctors who are based in the larger centres.1.1.1 Remote Health Service Delivery ModelsRemote health service delivery models are different from urban services due to theremote context. Remote services are typically characterised by geographical,professional and often social isolation of practitioners; a strong multidisciplinaryapproach; overlapping and changing roles of team members; a relatively high degreeof GP substitution; and practitioners requiring public health, emergency and extendedclinical skills.13 Remote practitioners are required to manage a full range of servicesacross the lifespan with often limited resources. The types of remote service deliverymodels include: Fly in fly out / drive in drive out models Primary health care clinics often led by remote area nurses and Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander health workers Hub and spoke models to provide allied health and specialist services that alsouse fly in fly out/ drive in drive out arrangements.1.1.2 Health Providers in Remote AustraliaThere are many different health service providers operating in remote areas, oftendelivering services in the same community. This occurs due to the state and territoryresponsibilities under the National Healthcare Agreement 2017 to improve healthoutcomes for all Australians.14 It involves specific funding programs to improveaccess to primary health care services including initiatives to prevent and managechronic disease care services.The type of service provider often depends on the population being served,geographic location and the model of service delivery. Health service providersinclude: State and territory government hospital and health services Aboriginal Community Controlled Services that are managed and led byAboriginal people Private and non-government organisations (NGOs) Mining, Defence Force, and other industries often led by paramedics, nurses oroccupational health and safety officers.151.1.3 Retaining the workforceGovernments and employers often have difficulty in recruiting and retaining healthprofessionals to live and work in remote areas. This has resulted in serious workforceshortages, extremely high turnover rates of staff, and maldistribution of mostworkforce groups.15 This is of concern when dealing with the management of chronicdisease, where continuity of care, a systems approach, and the overall managementof programs to maintain sustainability are of the highest importance. This iscompounded by generally poor orientation to remote practice, variable managementpractices and a rising number of staff employed on short term contracts throughrecruitment agencies.Best practice primary and secondary preventative interventions7

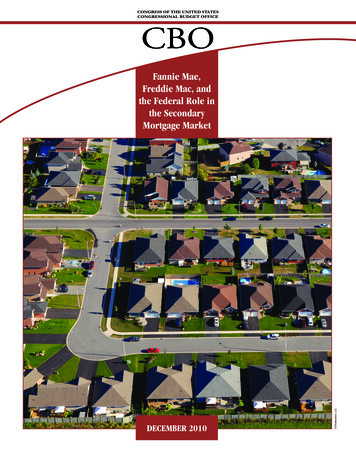

1.2 Public policy and health – the clinical contextPatients with chronic diseases have different needs to people with an acute illnessand require different solutions that include a comprehensive and systematicapproach to service delivery. In 1998 Wagner developed the Chronic Care Model toguide service providers to reorganise the health care system to better prevent andmanage chronic conditions.16 This approach is very different to the acute model ofcare in which health professionals are usually trained.1.2.1 Chronic disease model of careOver the last 11 years the Australian Government has developed the NationalChronic Disease Strategy17 and funded a number of initiatives to support services toredesign their health delivery systems. These include: the Healthy for LifeProgram,18 the Australian Primary Care Collaborative,19 and the One21seventyprogram.20 These initiatives supported services to move from an acute episodicapproach to service delivery to a systematic approach using the Chronic CareModel.4,21The Chronic Care Model identifies six domains within the health system that all needto be working effectively to build the capacity of individuals and the health team toimprove health outcomes. The domains are shown in Figure 1 and include:1.2.3.4.5.6.Organisational influence and integrationDelivery systems designClinical decision supportInformation systemsSelf-management support, andLinks with the community, other health services and other resources.Figure 1.1 The Chronic Care Model22The model is underpinned by the philosophy of continuous quality improvement tostrengthen the domains of the Chronic Care Model to achieve best practice in chronicdisease care. The MacColl Centre for Health Innovation developed a systemsassessment tool to help health services analyse their service delivery systems andBest practice primary and secondary preventative interventions8

identify areas for improvement.22 The tool has been adapted for use in Australia bydifferent states and territories.23-25 The adaptation for Indigenous primary health carecollapses the model into five domains combining the information systems anddecision support domains together.25 This recognises that current best practice is forprimary health care services to have an electronic information system with built-indecision support functions. Remote health services that implement the chronicdisease model, and actively participate in continuous quality improvement activities,are more likely to have a well-developed health system to improve healthoutcomes.261.2.2 Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme inremote AustraliaMedicare is the Australian Government funded health insurance scheme thatprovides free or subsidised health care services to the Australian population. TheMedicare system is largely structured around the work of private GeneralPractitioners (GPs) and medical specialists. The Medicare system is complimentedby the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) which is managed under theNational Medicines Policy and is designed to provide timely, reliable and affordableaccess to medicines and medicines services to ensure optimal health outcomes withconsideration of economic objectives.27Management of chronic and complex conditions by GPs is currently funded underthe fee-for-service based Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS) using a mix of timedand untimed Medicare items. These items pay GPs to assess, plan, coordinate andreview the health care of patients with chronic or terminal medical conditions andcomplex care needs. In addition, MBS provides fully paid five ‘untimed’ ChronicDisease Management benefits annually for clients to access allied health servicesfor multidisciplinary care.In remote areas, there are very few private GPs so a complementary system toaccess Medicare funding for GP services has evolved. In 2006, the Council ofAustralian Governments introduced the Section 19 (2) Health Insurance Act 1973Exemptions Initiative – Improving Access to Primary Care in Rural and RemoteAreas Initiative. The initiative provides access to Medicare funding to pay for prima

5. Enablers and barriers to best practice. 27 5.1 Enablers to best practice interventions 27 5.1.1 Improving primary prevention interventions 27 5.1.2 Improving secondary prevention interventions 28 5.2 Barriers to best practice and improved chronic disease outcomes 30 6.