Transcription

Edited by Rafi RomanoAssociate editors: Silvia Geron and Pablo EcharriLingual & EstheticOrthodonticsLondon, Berlin, Chicago, Tokyo, Barcelona, Beijing, Istanbul, Milan,Moscow, New Delhi, Paris, Prague, São Paulo, Seoul and Warsaw

vContentsIntroduction and Acknowledgments ixSection I:The Lingual Appliance: Brackets, Wiresand Accessories 1Chapter 1Development of the In-Ovation L Bracket from GAC Carlos F. Navarro, Marco A. Navarro, Jorge A. Villanueva3Chapter 2New Horizons in 2D Lingual Orthodontics Vittorio Cacciafesta15Chapter 3The Stealth System, Today and in the Future Antonio Veneziani(with the cooperation of Paolo Morandotti)29Chapter 4magic : Treatment Efficiency Meets Patient Comfort Rubens Demicheri41Chapter 5ORG Lingual Brackets Rafi Romano and Silvia Geron67Chapter 6STb: The Light Lingual System Luca Lombardo73Chapter 7The Phantom Bracket: Lingual Self-ligation and Esthetics Thomas W. Örtendahl87Chapter 8Lingual Orthodontic Cases Treated with OriginalHiro Brackets Toshiaki Hiro95Lingual & EstheticOrthodontics

viContentsChapter 9Lingual & EstheticOrthodonticsSelf-ligation and Traditional Ligation inLingual Orthodontics: Pros and Cons Alfredo Gilbert125Chapter 10 Customized Brackets and Archwires forLingual Orthodontic Treatment Rafi Romano147Chapter 11 3D Interactive Treatment Planning and Patient-SpecificAppliances Craig A. Andreiko157Chapter 12 The Manufacturing Process for LingualJet Pascal Baron, Christophe Gualano, Laurent Sempe,Ari Sciacca, and Geoffrey Hall167Chapter 13 Self-ligating Brackets in Lingual Orthodontics Hatto Loidl181Chapter 14 The Evolution Bracket: Clinical Experience Manabu Nakagawa193Chapter 15 Instruments Used in Lingual Orthodontics Victoria Burdess199

ContentsSection II:Updated Laboratory andSimulation Techniques Chapter 16 Digital Advancements in Lingual Orthodonticsand Laboratory Procedures Ari SciaccaChapter 17 Orapix System in Lingual Orthodontics Carla Maria Melleiro GimenezChapter 18 Indirect Bonding Technique in Lingual Orthodontics:The Hiro System Toshiaki Hirovii207209219239Chapter 19 In-house Lingual Bracket Transfer Systems Alfredo Gilbert255Chapter 20 A Modified Hiro System Within a Laboratory Sequence Peter Taylor275Chapter 21 Lingual Plain-Wire Appliance System Hee-Moon Kyung289Lingual & EstheticOrthodontics

viiiContentsSection III:Mechanics: from Alignment to Finishing Chapter 22 Tooth-Size Discrepancies and Stripping Carlos F. Navarro, Marco A. Navarro,Jorge A. Villanueva309Chapter 23 How to Control the Vertical Dimension with LingualOrthodontics Silvia Geron325Chapter 24 Theoretical Analysis of Maxillary Incisor Movementdue to Anteroposterior Force: Labial vs Lingual Tamar Brosh349Chapter 25 Interdisciplinary Treatment with Lingual Orthodontics Asif Chatoo361Chapter 26 Combining Lingual Orthodontics With Surgery Joan-Pau Marcó379Chapter 27 The Customized Hiro Transfer System Hatto Loidl399Chapter 28 Microimplant Anchorage in Lingual OrthodonticTreatment Hee-Moon KyungLingual & EstheticOrthodontics307407Chapter 29 Microimplants and Lingual Orthodontics Pablo Echarri427Chapter 30 Lingual Orthodontics in a Multidisciplinary Practice Laura Buso Frost461Chapter 31 Finishing with Lingual Orthodontics Silvia Geron489

ContentsSection IV:Tips and Tricks in Lingual Treatment 509Chapter 32 Paradigms in Lingual Orthodontics Julia Harfin511Chapter 33 Problems, Their Solutions, and Some Clinical Tips Henrique Valdetaro529Chapter 34 Clinical Considerations for the Establishmentof Facial Balance and Harmony Toru InamiChapter 35 Aluminum Oxide: To Use or Not To Use? Rita ThurlerChapter 36 Speech and Language Therapy: The Key toFunctional Control and Relapse Avoidance inLingual Orthodontic Treatments Diana GrandiChapter 37 Rotated Teeth in Lingual Orthodontics:Problems and Solutions Silvia Geron and Rafi RomanoChapter 38 It’s All in Your Hands: Food for Thought Federico I. Marconi Jr.ix563581593609617Lingual & EstheticOrthodontics

xContentsSection V:Clear and Esthetic Appliances Chapter 39 Invisalign: Effective and Accurate Treatment ofa Variety of Malocclusions Willy Z. DayanChapter 40 Lingual Orthodontics in Class II and Class IIIMalocclusions: The Microimplant-SupportedPendulum and Mechanics Lorenzo Favero and Vittorio FaveroChapter 41 Clear Aligner: Its Application and CombinedTreatment with Lingual Brackets TaeWeon KimSection VI:Future of Lingual Orthodontics Chapter 42 Future of the Lingual Orthodontics Technique Rafi RomanoIndex Lingual & EstheticOrthodontics631633649663677679685

Introduction and AcknowledgmentsxiIntroduction and AcknowledgmentsAlthough only just over a decade has passed since our first lingualbook (Lingual Orthodontics, B.C. Decker, 1998), myriad changes haveoccurred in lingual orthodontic techniques: numerous new bracketshave been presented by various companies, including individualizedcomputerized techniques; laboratory techniques have been upgradedand protocols are more detailed and simple; and biomechanics havebeen thoroughly investigated. As a result, lingual orthodontics has gainedpopularity and become part of the daily routine in many clinics.At the same time, a different esthetic option has emerged: clearaligners (Invisalign and the like). This has challenged practitioners toascertain the true advantages of the lingual technique over other estheticalternatives. The demand for esthetic treatment is constantly growing – atrend that will doubtless continue. Yet, the lingual technique still constitutes only a niche and lingual practitioners are still an exclusive group,meeting each other at the few meetings held worldwide.Although research and information on the lingual technique is stilldeficient, this book presents probably the most up-to-date informationavailable to the clinician. It covers not just a specific bracket or a specifictechnique, but the entire scope of options and information available.Thirty-four of the best clinicians from around the world, whopractice lingual orthodontics on a daily basis, have contributed theirexperiential knowledge in the most objective, noncommercial manner.The book does not aim to direct the orthodontist toward a specific treatment modality, but rather to review innovations in the technique and toserve as a reference source, which to date has unfortunately been lackingfor the lingual clinician.The book has been written and edited in a very short period oftime, to render it as up-to-date as possible. Being free of commercialLingual & EstheticOrthodontics

xiiIntroduction and Acknowledgmentsconstraints, I believe the book presents orthodontists with the broadestperspective and range of updates on the lingual technique.On a personal note, my lingual practice began soon after I completed my postgraduate programme. I was advised by a good friendin France to adopt this unique esthetic technique, and with his help Imet Dr Didier Fillion, who then was already one of the gurus of thetechnique. Dr Fillion’s enthusiasm and exclusive dedication to lingualtreatment inspired me and was one of the major reasons for editing myfirst textbook.Over the years, I have gained numerous personal friends withinthis field of orthodontics, many of whom gladly accepted my invitationto contribute to this textbook. I thank them most sincerely and profoundly for their commitment and motivation. Special thanks go to myassociate editors, Dr Silvia Geron and Dr Pablo Echarri.I am deeply grateful to Quintessence Publishing, especially to thepublisher Dr H. W. Haase and his son, Mr C. W. Haase, for their continued support. This is my third book to be published by Quintessence,and I have also been appointed Editor-in-Chief of ORTHODONTICS:The Art and Practice of Dentofacial Enhancement (formerly WJO) byQuintessence Publishing.I thank my personal assistant, Evelyn Rosenberg, and last but notleast my beloved family: my father, Dr Albert Romano, also a dentist,who inspired me and followed my developing career; my wife, Michal;and our four children, Emily, Lee-Ann, Illy, and Adam.Rafi Romano, DMD, MSCLingual & EstheticOrthodontics

The LingualAppliance:Brackets, Wires andAccessoriesICarlos F. NavarroMarco A. NavarroJorge A. VillanuevaVittorio CacciafestaAntonio VenezianiRubens DemicheriRafi RomanoSilvia GeronLuca LombardoThomas W. ÖrtendahlToshiaki HiroAlfredo GilbertCraig A. AndreikoPascal BaronChristophe GualanoLaurent SempeAri SciaccaGeoffrey HallHatto LoidlManabu NakagawaVictoria Burdess

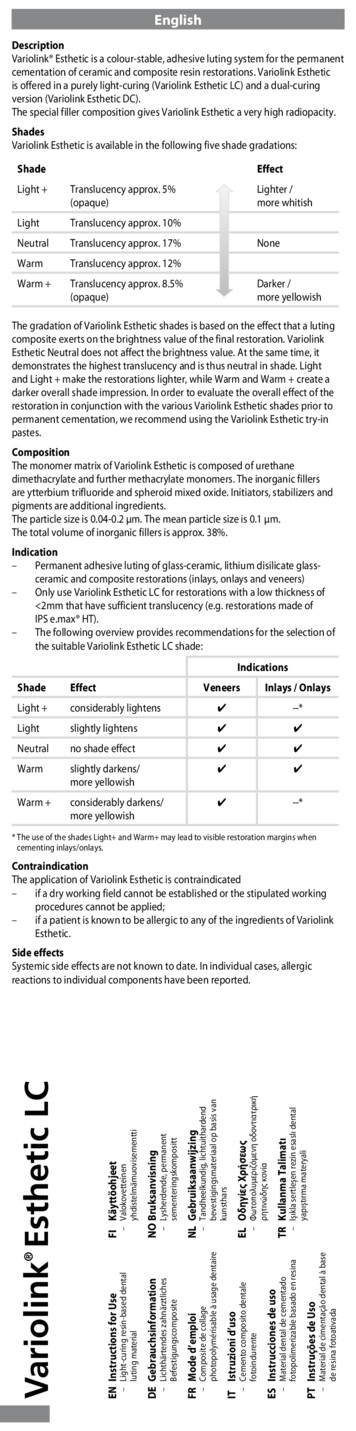

78Luca LombardoabcFig 6-4 (a to c) Case 1: Extraoral initial photographs.Social Six TreatmentThe so-called Social Six treatment is a clinical procedure proposed byScuzzo and Takemoto for the correction of all malocclusions with slightto moderate crowding or diastemata limited to the anterior portionof the maxillary and mandibular dentition. This is an invisible treatment, which necessitates no patient collaboration and limited chair-sidetime; patient comfort is favored due to the use of small brackets (STbs)attached only to incisors and canines and, in a small number of cases,the first premolars.Social Six generally involves the use of round, very light wires; itcannot be used in cases requiring torque control of one or more dental elements. Thus, the bracket positioning in this technique does notrequire complex laboratory procedures, and can therefore be performedby the orthodontist directly on the malocclusion model of the patient(simplified indirect bonding). Bracket transfer is then carried out bymeans of transfer masks; Scuzzo and Takemoto suggest that this is performed using thermoplastic glue to optimize precision.The first archwire to be positioned must be very resilient (0.012 or0.013-inch Ni-Ti or copper-nickel-titanium (Cu-Ni-Ti)) to ensure lightforces and rapid dental movements, and will remain in place for a periodof 5–16 weeks. If necessary, posttreatment finishing can be carried outusing a more rigid wire (0.016-inch Ni-Ti or TMA (beta-titanium)).Figures 6-4 to 6-11 illustrate a case of Class I dental malocclusionwith maxillary and mandibular diastemata treated via Social Six withSTb brackets. Figures 6-4 to 6-6 show the pretreatment situation.After an initial phase of tooth alignment using a 0.012-inch Ni-Tiarchwire (Fig 6-7), spaces were closed using elastic chains on a more rigid0.016-inch TMA archwire (Fig 6-8). Figures 6-9 to 6-11 show intraoraland extraoral images after treatment.The Lingual Appliance:Brackets, Wires andAccessories

STb: The Light Lingual SystemaFig 6-5 (a to e) Case 1: Intraoral initialphotos.bcde79baFig 6-6 (a, b) Case 1: Orthopantomogram and lateral cephalogram before treatment.Fig 6-7 (a, b) Case 1: Tooth alignmentusing a 0.012-inch Ni-Ti archwire.abFig 6-8 (a, b) Case 1: Space closure.abThe Lingual Appliance:Brackets, Wires andAccessories

228Carla GimenezFig 17-13 (left) Anterior viewof the dental arches in occlusionand the contact points – collisiontest.Fig 17-14 (right) Posterior viewof the dental arches in occlusionand the contact points – collisiontest.Fig 17-15 (left) Bracket positioning on the virtual setup.Fig 17-16 (right) Bracket positioning for a mushroom archwire.Fig 17-17 (left) Bracket positioning for a straight archwire.Fig 17-18 (right) Adjustment forbracket positioning in a 3D view.4. Virtual bracket positioningOnce the virtual setup is completed in the software library, the selectionof virtual lingual brackets is processed. All brackets will initially appearin the same virtual plane, parallel to the occlusal plane (Fig 17-15),and will be moved as a group to arrange the composition according toconventional bracket placement (mushroom archwire) (Fig 17-16) orlingual straight archwire (without in-out bend) (Fig 17-17). It is thenpossible to move each bracket individually to refine bracket positioning(Figs 17-18 and 17-19).The brackets can be moved vertically to find the ideal height, withlateral movements providing the ideal inclination, and in the sagittal planeto achieve the shortest distance between the bracket base and the enamelsurface to obtain the smallest resin pads possible (Fig 17-20). The programUpdated Laboratoryand SimulationTechniques

Orapix System in Lingual Orthodontics229Fig 17-19 (left) 3D bracketindividualization.Fig 17-20 (right) The resin padcan be minimized by adjustingthe bracket positioning.Fig 17-21 (left) Checkingbracket positioning with thearches in occlusion.Fig 17-22 (right) Clinical viewshowing resin pad sizes forincisor brackets with a mushroomarchwire.Fig 17-23 (left) Clinical viewshowing resin pad sizes forincisor brackets with a straightarchwire.Fig 17-24 (right) Canine bracket in slight rotation for straightwire technique.makes it possible to check whether the lingual brackets respect the teethlimits and whether there are any interferences when the maxillary and mandibular arches are in occlusion (Fig 17-21) and adjustments can be made.When mushroom archwires are used, the incisor brackets are relatively far from the lingual surfaces because their positions depend onthe thickness of the canines (Fig 17-22). In the lingual straight-wiretechnique, the position of the incisor brackets no longer depends oncanine thickness. The incisor brackets are placed with the maximumpossible contact with the lingual surfaces (Fig 17-23). To eliminatethe bends between canine and premolar, the canine brackets must beplaced in rotation (Fig 17-24) (distal offset); likewise, to eliminatethe bends between premolar and molar, the second premolar bracketsmust sometimes be slightly in rotation (according to the thickness of thefirst molars).Updated Laboratoryand SimulationTechniques

456Pablo EcharriFig 29-84 Molar intrusion.Fig 29-85 Detailing and finishing.Mechanics:from Alignmentto Finishing

Microimplants and Lingual OrthodonticsDeep-bite cases457Fig 29-86 Lingual brackets andlabial buttons.For the treatment of deep-bite cases with the intrusion of the incisors,the following is the protocol23:1.Indirect bonding of the lingual brackets and tubes to all maxillaryand mandibular teeth.2.A 0.016-inch Ni-Ti archwire for alignment and leveling and a0.0175 0.0175-inch TMA archwire for torque control (Fig 29-86).3.Insert a microimplant between the roots of the central and lateralincisors in the labial side and bond labial ceramic or plastic buttonsonto the labial surface of the upper incisors (Figs 29-87 and 29-88).4.Intrusion of the upper incisors, using elastic chain or light elastics(3.5 oz and 1/8 inch) from the microimplants to the labial buttons(Fig 29-89)5.Detailing and finishing with a 0.016-inch stainless steel or TMAarchwire (Fig 29-90).ConclusionMicroimplants enable more effective mechanics, which facilitates labialand lingual orthodontics and therefore reduces the treatment time.Mechanics:from Alignmentto Finishing

566Toru InamiPowell AnalysisSteiner Analysis Tweed AnalysisSEnasofrontal:115 130 nasofacial: 30 40 SLSNASNBANBSNDFMAFMIAnasomental:120 132 Z angleU–1 to NAnasolabial:90 120 Occl. to SNU1 to L1U lip to E lineL lip to E lineGo–Gn to SNmentocervical:80 95 aIMPAbPo to NBL1 to NBFig 34-2 (a) Powell cephalometric analysis. (b) Steiner and Tweed cephalometric analysis.4 measurements of the Tweed analysis and 4 measurements of the Powellanalysis (Fig 34-2).ResultsMean values of the pretreatment and posttreatment cephalometricmeasurements of the two groups were compared and tested for statisticalsignificance (Table 34-1).1.Many subjects in the straight group had maxillary protrusion withprotrusive A point, while there was a greater proportion of thehigh-angle and Class II malocclusions with retrognathic mandiblesin the convex group.2.ANB angle was successfully reduced in the straight group, whileANB angle reduction was difficult in the convex group.3.It was possible to retract point A, but very difficult to advancepoint B in both groups.4.There were no significant changes in FMA or SN-M angle ineither group, indicating that the mandibular plane angle was maintained without opening during lingual treatment.Summary of the StudyClass II malocclusions can be categorized into two clinical types, according to the profile changes obtained with treatment: straight type with profile improvement: Class II malocclusion dueto maxillary protrusion with protrusive A pointTips and Tricks inLingual Treatment

Clinical Considerations for the Establishment of Facial Balance and Harmony567Table 34-1 Results. The official approval of mean value and significant differenceStraight groupConvex stsignificancePostTxPre S-CsignificancePost 24576.671.50.20071.30.001**0.000**U1 to NA (mm)7.20.000**3.78.00.000**3.40.2560.381U1 to NA 1 to NB (mm)9.60.000**6.913.50.000**9.20.001**0.001**L1 to NB 2Po to NB0.30.001**1.3–1.50.048*–1.30.008**0.001**Po & L1 to NB9.30.000**5.615.00.000**10.50.001**0.000**U1 to l to SN17.00.021*18.120.40.021*22.50.0640.027*Go-Gn to SN37.50.46237.646.50.06947.00.001**0.000**SL (mm)46.30.15246.336.70.06235.90.006**0.001**SE (mm)19.60.13319.319.80.005**19.40.4480.499U-lip to -lip to 04**107.2106.20.003**113.50.0610.035*Student t-test, * P 0.05 ; **P 0.01. convex type without profile improvement: Class II malocclusiondue to a retrognathic mandible (particularly with a high-angle,dolichofacial pattern).The following clinical criteria for achieving facial balance and harmonyshould be considered in planning lingual orthodontic treatment. Clinical criterion 1: A proper interincisal angle should be established by adequately uprighting madibular incisors, which necessitates the application of good lingual root torque to the maxillaryincisors to prevent them from rabbiting.Tips and Tricks inLingual Treatment

640Willy Z. DayanFig 39-10 (left) ClinCheck withovercorrection of deep anterioroverbite.Fig 39-11 (right) Clinical resultof ClinCheck overcorrectionordered in Fig 39-10.images for a successful case of leveling of curve of Spee and deep bite withInvisalign, with no refinements or auxiliary treatment.The ClinCheck treatment plan (Fig 39-10) to create this levelingand room for restorations (Fig 39-11) was specified with overcorrection,just as would be the case with an accentuated reverse-curve archwire.The experienced Invisalign clinician learns to think of the whitesurfaces of the teeth (or edges of attachments) as the force applicationsurfaces and not necessarily as teeth positions in some types of movements.Treatment of Class II MalocclusionClass II correction is a very common challenge faced by clinical orthodontists. Class II correction for the nongrowing or adult patient poses aneven more complex set of clinical obstacles. Clinicians are encouraged tonot alter their Class II treatment philosophy. Instead, clinicians shoulduse Invisalign as a tool in their armamentarium. The treatment of ClassII malocclusion in an adult is illustrated below. The author’s philosophy is to approach the case with a technique to first correct the Class IImolar relationship, and then later to correct the crowding and deep biteelements of the case. This has been the approach used for many cases.Clinicians may choose to distalize molars with other appliances, suchas the Distal Jet , Pendulum, T Rex , Frog , Celtin , or Carriere .All these appliances can be incorporated into Invisalign treatment. Theclinician sets up the case using the appliance(s) of choice and then incorporates Invisalign to help obtain individual ideal treatment goals. Theadvantage of continuing to treat cases in the same way the clinician hasin the past is that the only element that has changed is the Invisalign tool.This allows the clinician to compare the effectiveness of Invisalign withhis or her previous experiences.The case illustrated in Fig 39-12 is a typical Class II adult case thatwas corrected with Invisalign. Treatment began with a maxillary removable appliance (distalization screws) with adjunct anchorage provided byClear and EstheticAppliances

Invisalign: Effective and Accurate Treatment of a Variety of Malocclusions641Fig 39-12 (a, b) Before treatment of Class II, division 2, malocclusion.abFig 39-13 (left) Maxillaryremovable appliance to distalizemolars.Fig 39-14 (right) Class II elastics to lower buttons with lowerEssix retainer.Fig 39-15 (a, b) Class IIelastics to lower buttons duringInvisalign.abClass II elastics (supported by a mandibular vacuum-formed retainer), asshown in Figs 39-13 and 39-14.Once the maxillary molars were distalized, Invisalign couldbe used to sequentially distalize the premolars and then the anteriorteeth, thus decreasing the overjet and correcting the dental Class IImalocclusion. Note that with braces, patients use Class II elastics toavoid anchorage loss during this second phase of correction; this isalso the case with Invisalign, where Class II elastics are used fromthe mesial aspect of the maxillary canines to bonded buttons onthe mandibular second molars (Fig 39-15; however note that thisfigure shows a different case, to demonstrate the use of elastics withInvisalign).Clear and EstheticAppliances

book (Lingual Orthodontics, B.C. Decker, 1998), myriad changes have occurred in lingual orthodontic techniques: numerous new brackets have been presented by various companies, including individualized computerized techniques; laboratory techniques have been upgraded and protocols are more detailed and simple; and biomechanics have .