Transcription

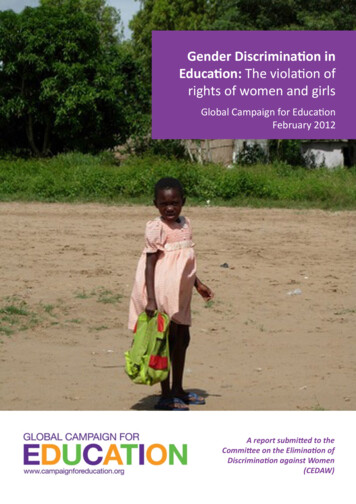

Gender Discrimination inEducation: The violation ofrights of women and girlsGlobal Campaign for EducationFebruary 2012A report submitted to theCommittee on the Elimination ofDiscrimination against Women(CEDAW)

TABLE OF CONTENTSPART I: Introduction .3CASE STUDY 1: Bolivia .5PART II: The nature of gender discrimination in education .6PART III: Necessary state action .9PART IV: Initial survey results .10CASE STUDY 2: Armenia .12PART V: Conclusions and recommendations .14REFERENCES .15CASE STUDY 3: Pakistan .16CASE STUDY 4: Tanzania .17ANNEX 1: Availability Table .18LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1: Percentage of respondents unhappy being a girl or a boy .10Figure 2: Gender stereotyping of subject aptitude .11Figure 3: Teachers’ experience of gender discrimination .11This report is independently published by the Global Campaign for Education (GCE). GCE is a civil society coalition whichcalls on governments to deliver the right of everyone to a free, quality, public education.Global Campaign for Education Global Campaign for Education 2012All rights reserved25 Sturdee AvenueRosebank, Johannesburg 2132South Africawww.campaignforeducation.orgCover image: GCE Mozambique (Movimiento de Educação para Todos)Pages 8-9 image VSO RwandaPage 13 Agencia Brasil/Marcello Casal JrAll other images Global Campaign for Education

PART 1: Introduction2. Education is strongly embedded in CEDAW, inways that reflect this rich relationship between genderequality and the right to education. CEDAW article 10explicitly enshrines the right to equality in education,while many other articles – notably 5 (on social andcultural norms), 7 (on civil and political participation), 8(on international representation), 11 (on employment),14 (on the social, economic and cultural rights of ruralwomen) and 16 (on rights to and within marriage, andwomen’s reproductive rights) – express rights of which thefull realization is very strongly dependent on addressinggender discrimination in education. Moreover, CEDAW’sGeneral Recommendation 3, as well as article 10 of themain convention, expresses clearly the role of educationin addressing wider gender discrimination based onstereotyping and biased cultural norms.4. There has been undeniable progress made inimproving gender parity in education in the threedecades since the entry into force of CEDAW. Parity inenrolment has accelerated over the 22 years since the firstagreement of the Education For All framework in Jomtien,and since agreement of the Millennium DevelopmentGoals in 2000. The number of girls out of school fellby more than 40% from 1999 to 2008ii, and girls nowconstitute 53% of those children out of school, as opposedto 60% at the start of the millennium. The MDGs calledfor gender parity at primary and secondary education by2005, a target that was clearly missed; nevertheless, it isencouraging that at an aggregate level, the world is nowcloser to achieving gender parity, at least so in primaryeducation.Gender Discrimination in Education: The violation of rights of women and girls1. There are multiple and diverse links between genderequality and the fulfillment of the human right toeducation. The pervasive denial of the human rightto education experienced by women and girls acrossthe globe – as shown, for example, by the fact that twothirds of the world’s non-literate adults are women – is astriking example of gender discrimination. Education isan enabling and transformative right. As pointed out bythe Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights(CESCR), the right to education “has been variouslyclassified as an economic right, a social right and acultural right. It is also a civil right and a political right,since it is central to the full and effective realization ofthose rights as well. In this respect, the right to educationepitomizes the indivisibility and interdependence of allhuman rights”i. A strong education system, in line withthe principle of non-discrimination, is key for redressinggender injustice in wider society, and for overcomingsocial and cultural norms that discriminate against girlsand women. CESCR has also clearly stated that “theprohibition against discrimination enshrined in article2 of the Covenant [of Economic, Social and CulturalRights] is subject to neither progressive realizationnor the availability of resources; it applies fully andimmediately to all aspects of education and encompassesall internationally prohibited grounds of discrimination”.The Global Campaign for Education (GCE) thereforesees the challenge posed by gender discrimination ineducation as multiple: policy and practice in educationneeds to be re-oriented to ensure the deconstruction ofgender stereotypes as well as the promotion of equalityof experience and relations for both sexes in education,thus addressing power imbalances that perpetuate genderinequality and leveraging access to all rights by womanand girls.3. The human right to education and nondiscrimination is further affirmed by a number ofother international treaties. Along with the clearexpression of a universal right to education in Article 26of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and theprovisions on gender-equitable education in CEDAW, themost significant expressions of these rights are found inthe Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989),the International Covenant on Economic, Social andCultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966) and the 1960 UNESCOConvention against Discrimination in Education.Governments further committed themselves to ensuringgender equality in education in the Dakar Frameworkfor Action (2000), the Millennium Development Goals(2000), the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action(1995) and the World Declaration on Education For All(1990), which stated that “the most urgent priority is toensure access to, and improve the quality of, educationfor girls and women, and to remove every obstaclethat hampers their active participation.” Yet despitethese numerous treaties, States and the internationalcommunity still largely treat education as a developmentgoal and not as a right. GCE believes that a clearrights-based understanding of education is crucial toovercoming gender discrimination and to re-orientingeducation towards the promotion of greater genderequality in society as a whole.5. Progress on enrolment, however, should not mask thefact that girls and women continue to be denied theirrights throughout the education cycle, and still facehuge discrimination and disadvantage in terms of access,progress, learning and their experience in schools. Thetarget of achieving gender parity in school enrolmentsgained significant traction in the international communitynot least because of its inclusion in the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs). But the consequentprogress has led to a dangerous complacency about thereduction of gender inequality in education. Girls are stillfar more likely to drop out before completing primaryeducation, have markedly worse experience in school,often characterized by violence, abuse and exploitation,and have scant chance of progressing to secondary schooland tertiary education. The preliminary findings ofGCE’s global survey of gender in schools show that morethan one fifth of girls in secondary schools are unhappy3

with their gender, and nearly two fifths have been madefun of at school for being a girl. In sub-Saharan Africa,there is a 10 percentage point gap between girls’ andboys’ primary school completion rates, and in onlyseven of the 54 countries in sub-Saharan Africa do girlshave a greater than 50% chance of going to secondaryschool. GCE’s survey shows that gender stereotypes stillprevail in schools, particularly around male and femaleaptitudes, as do unequal power relations, as shown in, forinstance, the fact that girls are far more likely to performclassroom chores. This perpetuates gender inequalitieswithin the education system and society as a whole. Itis hardly surprising, then, that nearly two-thirds of theworld’s illiterate people are women. True gender equalityin education — and beyond — remains far from beingachieved.6. The Global Campaign for Education (GCE) is acivil society coalition which calls on governments toact immediately to deliver the right of every girl, boy,woman and man to a free quality public education.Since our formation in 1999, millions of people andthousands of organizations – including civil societyorganizations, trade unions, child rights campaigners,teachers, parents and students – have united to demandEducation for All. We believe that quality public educationfor all is achievable, and we therefore demand thatgovernments north and south take their responsibilityto implement the Education for All goals and strategiesagreed by 180 world governments at Dakar, in April 2000,and since agreed time and again.Global Campaign for Education7. GCE’s Global Action Week in 2011 focused ongender equality in education. GCE mobilized membersand schools in over 100 countries to discuss genderdiscrimination in education, and to call for politiciansto ‘Make it Right’ for gender equality in education. Wepresented parliamentarians, ministers and heads of statewith demands in the form of manifestos and petitions.Our coalitions joined forces with national women’s groups4and enlisted the support of high-profile women to amplifyour demands. The GCE coalition continues to campaignand lobby on the global, regional and national stage toensure gender justice prevails within and beyond schools.8. With this report, GCE seeks to present the CEDAWcommittee with information that indicates the currentstate of gender equality in education globally. Inorder to do so, we draw on GCE’s own report jointlyproduced with RESULTS from 2011, Make It Right:ending the crisis in girls’ education, which included ananalysis of girls’ education in 80 developing countries;on information supplied by GCE member coalitionsbefore and during 2011 Global Action Week on genderand education and on the preliminary results of ongoingparticipatory research on gender discrimination inschools, which GCE and its membership is conductingwith students, teachers and the community. Part II ofthis report sets out the rights-based framework throughwhich we will analyze gender equality in education,and presents an overview of progress and key areas ofconcern, while Part III indicates the kinds of State actionsneeded to address these issues. In Part IV, we present thepreliminary results of the participatory research (dueto be concluded in mid-2012 and the conclusions fromwhich shall be formally presented to CEDAW). We finishwith conclusions and recommendations in Part V, withour predominant focus on national-level action that canand should be taken by CEDAW’s State signatories, interms of the legal, political and financial frameworks thatwill support gender equality in education. The reportalso includes brief national case studies, from differentregions, which present examples of some of the differentforms of gender discrimination in education. The premiseof this report is that human rights law should be moreexplicitly recognized as the primary foundation for effortsto achieve Education For All, and more specifically genderequality in education, and that this recognition will entailan appropriate focus on State responsibility and capacity.

CASE STUDY 1: BOLIVIALegislative and policy contextBolivia ratified CEDAW without reservations in 1990 and the optional Protocol in 2000. The constitution guarantees equalrights for men and women; yet women generally have a lower level of protection than men. Living conditions for Boliviaare among the worst in Latin America, and women are often the victims of violence and discrimination. The degree ofdiscrimination is even greater for indigenous women, gender inequality is deeply entwined with class stratification and ishard to bring to light.The numbersThirteen percent of adult women in Bolivia cannot read and write, compared to just 5% of men, but there is some sign ofprogress in efforts to educate young generations. The net primary enrolment rate for girls is 94%, and Bolivia also reportsa 94% rate of girls’ transition to secondary education. Overall net enrolment rates for secondary education are, however,much lower (for both boys and girls) at just 69%.ViolenceOne significant problem which affect women’s and girls’ ability to realize their right to education is violence. Physicalintegrity is not sufficiently protected and this has created a serious crisis in education. Fifty percent of Bolivian womenare believed to have suffered physical, psychological or sexual violence at the hands of men, and a study by Child DefenseInternational Bolivia found that there are at least 100 cases of sexual attacks on children at school, every day. Until schoolsare guaranteed to be safe spaces for girls, this problem will continue to have a huge impact on girls’ and women’s education.PregnancyGender Discrimination in Education: The violation of rights of women and girlsOf great concern is the ill treatment of pregnant girls. Although national education policy allows pregnant girls to continuewith schooling, they are repeatedly excluded because school authorities bow to societal pressure against keeping pregnantgirls in school. Civil society groups are currently contesting the decision of school authorities in El Alto to exclude two finalyear pregnant girls from school. They were re-enrolled in line with national education policy but due to reprisals from thepublic, the girls were once again excluded.Multiple discriminationIndigenous women are disproportionately targeted by discrimination. For example, Amalia Laura is a 23 year old lawgraduate who suffered repeated discrimination based on her indigenous and rural background, while taking her universitydegree at an urban center. She was targeted for the traditional indigenous way she wore her hair and clothes throughout theyears and her college graduation picture was altered by classmates, transforming her dressing into the toga she had refusedto wear for the occasion, in a clear demonstration of intolerance, abuse and discrimination. She took the case to court.Civil society actionIn the last few years, the Bolivian Campaign for the Right to Education and its allies have carried out a number ofimportant initiatives addressing gender discrimination at national and local levels. Civil society pressure helped ensure thatthe new National Education Law affirms that the Bolivian State will promote education free of patriarchy, and a new lawagainst violence in schools is currently being discussed in Parliament. Civil society organizations are campaigning for a newcurriculum to be agreed, based on gender equity, for both primary and secondary education. The campaign also works hardto raise awareness, share information and increase citizen participation in education policy. Adult learners have also beeninvited to take part in the process – they have been involved especially in the 2011 Global Action Week, debating how agender perspective can change education.Bolivian Campaign for the Right to Education; CDI-Bolivia; UNESCO Institute of Statistics (http://www.uis.unesco.org)5

PART II: The nature of genderdiscrimination in education9. GCE understands education to be a right, andanalyzes it through the ‘4A’ framework, whichencompasses availability, accessibility, acceptability, andadaptability. The 4A framework was developed by theformer UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education,the late Katarina Tomasevski , and adopted by the CESCRin 1999. In this submission, and drawing on the workof ActionAidiii and the Right to Education Project, weselect criteria and indicators for each of the four As thatare most relevant to the experience of girls and womenin education, and to the role of education in combatingbroader gender discrimination. We therefore ask thefollowing questions:Is education available to girls and women, throughoutthe cycle, and not simply in terms of primary levelenrolments?Is education accessible, in terms of the absence offinancial, physical, geographical and other barriers?Is education acceptable for girls and women as well asboys and men, in terms of its content, form and structure– both what is being taught and learned, and how thatteaching and learning happens?Is education adaptable, in terms of being responsiveto girls’ and boys’ different needs and lives, taking intoaccount phenomena such as girls’ and women’s labour,early marriage and pregnancy?Some of the relevant issues may cut across differentAs; they can be inherent to the school system (such ascurriculum), or have a much broader scope (such as childlabour or gender stereotyping).Global Campaign for Education10. GCE’s analysis of the availability of education in 80developing countries finds very mixed progress, butacross the board there is a shocking disconnect betweengirls’ access to primary schooling and their ability toenjoy a full cycle of education. Our ‘availability table’ (seeannex I) tracks the current status of and recent progress ingirls’ enrolment, attendance, learning and transition fromprimary through to tertiary levels. Of the 80 countries, werate 20 as strong performers, 18 as middling, 16 as weakand eight as failing. A further 18 countries do not havesufficient data to assess their progress – itself an indicationof a lack of attention to girls’ education. It should be notedthat even in countries rated as strong performers, the rateof girls’ continued attendance and transition to secondaryeducation can be woeful. Tanzania, for example, scoreshighly because of vast improvements in enrolment; butonly 32% of the girls who complete primary school makethe transition to lower secondary. In Burundi, girls’6primary enrolment increased a remarkable 200%; yetone quarter of enrolled girls will drop out before grade 5and, of those female students remaining, only 22% willmake the transition to lower secondary. In fact, in 47out of 54 African countries, girls have less than a 50%chance of completing primary school. The very low ratesof continued attendance and, in particular, transition tosecondary education, are a stark reminder of why we needto look beyond primary school enrolment figures (oftenmeasured only on the first day) and track availability morecomprehensively, including in early childhood care andeducation, on which there is still extremely scarce data.11. Whilst improving availability of girls’ educationwill require investment, our analysis shows that thereis no simple link between a country’s income level andits performance. Of the 24 weak or failing countries,half are low-income countries, and half are middleincome. Of the 20 strong performers, five are low-incomecountries. This indicates clearly that appropriate policiescan be successfully implemented (or not) regardless of acountry’s overall wealth.12. Looking at the policies of successful countries interms of availability of education for girls, GCE hasidentified the provision of early childhood care andeducation (ECCE), improved non-formal educationfor adult women, and removing barriers to secondaryeducation as all being crucial.ECCE: World Bank studies, among others, haveestablished that girls provided with pre-primary educationstay enrolled in and attend school for longeriv, whilstECCE eases the caring burden on older girls and women.Yet in low-income countries only 18% of children areprovided with a pre-primary educationv.Youth and adult education: given that two thirds ofthe world’s 796 million non-literate adults are women – alegacy of women’s exclusion from formal education andof their rights being violated – a focus on quality andappropriate youth and adult education is key to repairsuch legacy. Yet provision is patchy, under-funded, andunder-emphasized. Governments should invest at least3% of their budgets in youth and adult education, as manyhave previously committed to do.Post-primary barriers: secondary education remainsout of reach for millions of girls, and tertiary even moreso. In the Central African Republic, Niger, Chad andMalawi, for example, fewer than 1 in 200 girls go touniversity. Systemic barriers include a number of culturalfactors, as well as significant cost barriers.Explanations of the (un)availability of education for girlsand women are also to be found through analyzing theother 3As: accessibility, acceptability and adaptability.13. The financial costs associated with schooling, whichcan affect accessibility for all, have a disproportionateimpact on girls. Analysis abounds of the gendered impactof school fees (and other associated costs of schooling),

which combine with a preference for educating boys toimpact girls disproportionately. Basic education shouldtherefore be both free – genuinely so, with adequatefinance provided to schools – and compulsory. Theseelements have been found to address both the reality andthe perception that it is more valuable to educate boysvi.In Uganda, the introduction of free primary educationcaused total girls’ enrolments to rise from 63% to 83%,and enrolments of the poorest fifth of girls from 46%to 82%vii. Given the lack of accessibility of secondaryeducation for girls, it is extremely important that Statesextend free education to this level, as established inGeneral Recommendation 13 of CESCR that affirms“States parties are required to progressively introducefree secondary and higher education”. Beyond directfees for education, it is also necessary to provide supportfor the associated costs of education, such as schoolmaterial, transport and food, which often lead parents tokeep children out of school, particularly during times ofeconomic hardship. Research published collaborativelyby a number of organizations and US universities inearly 2012 reported that many young women in postearthquake Haiti are exchanging sex for payment ofeducational expenses: this is just one shocking exampleof the coping mechanisms in place when education is notfreely available, and the exploitation that such situationsfacilitateviii.and mechanisms to ensure safe transport, which may beas simple as ensuring adult accompaniment for childrentravelling to school.14. Opportunity costs must also be tackled upfront, asthere are important associated gender impacts, relatedin particular to the above mentioned overall preferenceto prioritize boys education. Child labour is a centralobstacle to the fulfilment of the right to education, withover one fifth of the world’s children aged 5-17 yearsbeing exploited by child labour, a huge proportion ofwhich relates to domestic servants, primarily carried outby girls. We highlight that “child domestic work is a clearexample of how gender identity contributes to the shapingof the different kinds of labour. Child domestic labourpatterns correspond to deep-seated, sex-based divisions oflabour”, being a clear reflection of gender discriminationix.Legislation that combats child domestic labour is key toovercoming gender associated inequalities in access toeducation. It is worth noting that stipend programs andconditional cash transfer programs have been employedin settings as diverse as Brazil, Yemen, Nepal, Tanzania,Malawi, Madagascar, Gambia and Kenya, and havesucceeded in reducing girls’ drop-out rates and delayingearly marriage.17. Making education more acceptable for girls alsoinvolves ensuring that the curriculum, the classroomand school culture are of high quality, uphold rights,and are relevant and safe. In terms of curriculumreform, a greater emphasis is needed both on includingequal and positive representation and images of women,and in ensuring that relevant skills and knowledge –including around sexual and reproductive health – areincluded. Along with improvements in the overall qualityof education, these curriculum reforms could do muchto address perceptions and reality of the low value ofeducation, which acts as a disincentive for parents toeducate their daughters. In terms of classroom culture,teachers must ensure full participation of women andgirls in the classroom – which itself may involve a breakwith cultural norms – and schools need to work harderto avoid directing boys and girls into subjects, activitiesand games deemed ‘appropriate’ for their gender. GCE’ssurvey showed that overall around half of pupils stilltend to identify so-called ‘soft’ subjects with girls, andmore technical subjects with boys, with the associationsstrongest in South Asia. The majority of pupils wereaware of games that they described as being “only” forgirls or for boys. School safety is a huge issue for girls: attheir best, schools can provide girls with protection fromviolence and abuse, through the act of educating them; attheir worst, they are a site of abuse. Surveys conducted byGCE members indicate that violence against and abuseof girls often exists alongside a culture of impunity, inwhich abuse is rarely reported or punished. Requiredaction includes not only monitoring and enforcement oflegislation, but improved school infrastructure, trainingfor teachers and parents, more female teachers andcurriculum reform.Gender Discrimination in Education: The violation of rights of women and girls15. The distance of schools and the lack of adequatefacilities both have a significant effect on theaccessibility of education for girls, particularly interms of the provision of sanitary facilities for girls. Inresearch conducted in Uganda, 61% of girls reportedstaying away from school during menstruationx. A lackof adequate, separate facilities and can also increasevulnerability to and fear of sexual assault and violence.Similarly, when children have to travel long distancesto school, parents are more likely to prevent girls fromgoing to school because of fears for their safetyxi. Thisrequires both greater provision of schools in rural areas16. Addressing the lack of female teachers is asignificant element in making education moreacceptable for girls. This can have a direct impact onenrolment, with the correlation especially strong in subSaharan Africa and at secondary levelxii. Yet only aroundone third of secondary school teachers in South and WestAsia are female and fewer than three in 10 in sub-SaharanAfrica. Disparities can be even greater at tertiary level:in Ethiopia, for example, fewer than 1 in 10 tertiary levelteachers are female. The absence of women teachers fromthis level is perpetuated and exacerbated by the systemiclack of opportunities for girls and women to accessrequired skills and trainingxiii. Those women who doenter teaching can suffer gender discrimination in theirprofession: the preliminary results of GCE’s global teachersurvey show a huge 30% of female teachers reporting thatthey have experienced gender discrimination. In regionswhere the teaching profession has become feminized,however, this has in some cases contributed to its lowstatus and pay. There needs to be simultaneous effortsto raise the status of the teaching profession, whilstsupporting greater female participation in regions wherethis is very low.7

18. In November 2010 there were hearings at the CESCRon sexual and reproductive rights and GCE supportsa greater emphasis on the need to address the direct,indirect and structural determinants that may influencethe level of enjoyment of sexual and reproductivehealth. These determinants, which include women’s levelof education, relate to the enjoyment of all other humanrights. As the former UN Special Rapporteur on the rightto education, Vernor Muñoz, has noted, education playsa key role in promoting sexual and reproductive rights:“There is no valid excuse for not providing people withthe comprehensive sexual education that they need inorder to lead a dignified and healthy life.”19. The educational system must be adaptable tostudents’ different contexts and interests;

schools, which GCE and its membership is conducting with students, teachers and the community. Part II of . are among the worst in Latin America, and women are often the victims of violence and discrimination. The degree of discrimination is even greater for indigenous women, gender inequality is deeply entwined with class stratification and .