Transcription

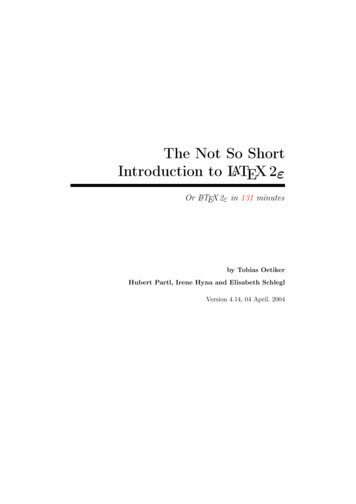

The Not So ShortIntroduction to LATEX 2εOr LATEX 2ε in 131 minutesby Tobias OetikerHubert Partl, Irene Hyna and Elisabeth SchleglVersion 4.14, 04 April, 2004

iiCopyright 1995-2002 Tobias Oetiker and all the Contributers to LShort. Allrights reserved.This document is free; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the termsof the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation;either version 2 of the License, or (at your option) any later version.This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUTANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITYor FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the GNU General PublicLicense for more details.You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License along withthis document; if not, write to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 675 Mass Ave,Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Thank you!Much of the material used in this introduction comes from an Austrian introduction to LATEX 2.09 written in German by:Hubert Partl partl@mail.boku.ac.at Zentraler Informatikdienst der Universität für Bodenkultur WienIrene Hyna Irene.Hyna@bmwf.ac.at Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung WienElisabeth Schlegl noemail in GrazIf you are interested in the German document, you can find a versionupdated for LATEX 2ε by Jörg Knappen atCTAN:/tex-archive/info/lshort/german

ivThank you!While preparing this document, I asked for reviewers on comp.text.tex.I got a lot of response. The following individuals helped with corrections,suggestions and material to improve this paper. They put in a big effort tohelp me get this document into its present shape. I would like to sincerelythank all of them. Naturally, all the mistakes you’ll find in this book aremine. If you ever find a word that is spelled correctly, it must have been oneof the people below dropping me a line.Rosemary Bailey, Marc Bevand, Friedemann Brauer, Jan Busa,Markus Brühwiler, Pietro Braione, David Carlisle, José Carlos Santos,Neil Carter, Mike Chapman, Pierre Chardaire, Christopher Chin, Carl Cerecke,Chris McCormack, Wim van Dam, Jan Dittberner, Michael John Downes,Matthias Dreier, David Dureisseix, Elliot, Hans Ehrbar, Daniel Flipo, David Frey,Hans Fugal, Robin Fairbairns, Jörg Fischer, Erik Frisk, Mic Milic Frederickx,Frank, Kasper B. Graversen, Arlo Griffiths, Alexandre Guimond, Andy Goth,Cyril Goutte, Greg Gamble, Frank Fischli, Neil Hammond,Rasmus Borup Hansen, Joseph Hilferty, Björn Hvittfeldt, Martien Hulsen,Werner Icking, Jakob, Eric Jacoboni, Alan Jeffrey, Byron Jones, David Jones,Johannes-Maria Kaltenbach, Michael Koundouros, Andrzej Kawalec,Sander de Kievit, Alain Kessi, Christian Kern, Jörg Knappen, Kjetil Kjernsmo,Maik Lehradt, Rémi Letot, Flori Lambrechts, Johan Lundberg, Alexander Mai,Hendrik Maryns, Martin Maechler, Aleksandar S Milosevic, Henrik Mitsch,Claus Malten, Kevin Van Maren, Richard Nagy, Philipp Nagele,Lenimar Nunes de Andrade, Manuel Oetiker, Urs Oswald, Demerson Andre Polli,Maksym Polyakov Hubert Partl, John Refling, Mike Ressler, Brian Ripley,Young U. Ryu, Bernd Rosenlecher, Chris Rowley, Risto Saarelma,Hanspeter Schmid, Craig Schlenter, Gilles Schintgen, Baron Schwartz,Christopher Sawtell, Miles Spielberg, Geoffrey Swindale, Laszlo Szathmary,Boris Tobotras, Josef Tkadlec, Scott Veirs, Didier Verna, Fabian Wernli,Carl-Gustav Werner, David Woodhouse, Chris York, Fritz Zaucker, Rick Zaccone,and Mikhail Zotov.

PrefaceLATEX [1] is a typesetting system that is very suitable for producing scientificand mathematical documents of high typographical quality. It is also suitablefor producing all sorts of other documents, from simple letters to completebooks. LATEX uses TEX [2] as its formatting engine.This short introduction describes LATEX 2ε and should be sufficient formost applications of LATEX. Refer to [1, 3] for a complete description of theLATEX system.This introduction is split into 6 chapters:Chapter 1 tells you about the basic structure of LATEX 2ε documents. Youwill also learn a bit about the history of LATEX. After reading thischapter, you should have a rough understanding how LATEX works.Chapter 2 goes into the details of typesetting your documents. It explainsmost of the essential LATEX commands and environments. After readingthis chapter, you will be able to write your first documents.Chapter 3 explains how to typeset formulae with LATEX. Many examplesdemonstrate how to use one of LATEX’s main strengths. At the endof the chapter are tables listing all mathematical symbols available inLATEX.Chapter 4 explains indexes, bibliography generation and inclusion of EPSgraphics. It introduces creation of PDF documents with pdfLATEX andpresents some handy extension packages.Chapter 5 shows how to use LATEX for creating graphics. Instead of drawing a picture with some graphics program, saving it to a file and thenincluding it into LATEX you describe the picture and have LATEX drawit for you.Chapter 6 contains some potentially dangerous information about how toalter the standard document layout produced by LATEX. It will tell youhow to change things such that the beautiful output of LATEX turns uglyor stunning, depending on your abilities.

viPrefaceIt is important to read the chapters in order—the book is not that big, afterall. Be sure to carefully read the examples, because a lot of the informationis in the examples placed throughout the book.LATEX is available for most computers, from the PC and Mac to large UNIXand VMS systems. On many university computer clusters you will find thata LATEX installation is available, ready to use. Information on how to accessthe local LATEX installation should be provided in the Local Guide [5]. If youhave problems getting started, ask the person who gave you this booklet.The scope of this document is not to tell you how to install and set up aLATEX system, but to teach you how to write your documents so that theycan be processed by LATEX.If you need to get hold of any LATEX related material, have a look at oneof the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (CTAN) sites. The homepage isat http://www.ctan.org. All packages can also be retrieved from the ftparchive ftp://www.ctan.org and its various mirror sites all over the world.They can be found e.g. at ftp://ctan.tug.org (US), ftp://ftp.dante.de(Germany), ftp://ftp.tex.ac.uk (UK). If you are not in one of these countries, choose the archive closest to you.You will find other references to CTAN throughout the book, especiallypointers to software and documents you might want to download. Instead ofwriting down complete urls, I just wrote CTAN: followed by whatever locationwithin the CTAN tree you should go to.If you want to run LATEX on your own computer, take a look at what isavailable from CTAN:/tex-archive/systems.If you have ideas for something to be added, removed or altered in thisdocument, please let me know. I am especially interested in feedback fromLATEX novices about which bits of this intro are easy to understand andwhich could be explained better.Tobias Oetiker oetiker@ee.ethz.ch Department of Information Technology andElectrical Engineering, Swiss Federal Institute of TechnologyThe current version of this document is available onCTAN:/tex-archive/info/lshort

ContentsThank you!iiiPrefacev1 Things You Need to Know1.1 The Name of the Game . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.1.1 TEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.1.2 LATEX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.2 Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.2.1 Author, Book Designer, and Typesetter1.2.2 Layout Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.2.3 Advantages and Disadvantages . . . . .1.3 LATEX Input Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.3.1 Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.3.2 Special Characters . . . . . . . . . . . .1.3.3 LATEX Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.3.4 Comments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.4 Input File Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.5 A Typical Command Line Session . . . . . . . .1.6 The Layout of the Document . . . . . . . . . .1.6.1 Document Classes . . . . . . . . . . . .1.6.2 Packages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.6.3 Page Styles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1.7 Files You Might Encounter . . . . . . . . . . .1.8 Big Projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1111222344456679991111132 Typesetting Text2.1 The Structure of Text and Language2.2 Line Breaking and Page Breaking . .2.2.1 Justified Paragraphs . . . . .2.2.2 Hyphenation . . . . . . . . .2.3 Ready-Made Strings . . . . . . . . .2.4 Special Characters and Symbols . . .15151717181919.

viiiCONTENTS2.52.62.72.82.92.102.112.122.132.4.1 Quotation Marks . . . . . . . . . . .2.4.2 Dashes and Hyphens . . . . . . . . .2.4.3 Tilde ( ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.4.4 Degree Symbol ( ) . . . . . . . . . .2.4.5 The Euro Currency Symbol ( ) . . .2.4.6 Ellipsis (. . . ) . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.4.7 Ligatures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.4.8 Accents and Special Characters . . .International Language Support . . . . . . .2.5.1 Support for Portuguese . . . . . . .2.5.2 Support for French . . . . . . . . . .2.5.3 Support for German . . . . . . . . .2.5.4 Support for Korean . . . . . . . . . .2.5.5 Support for Cyrillic . . . . . . . . . .The Space Between Words . . . . . . . . . .Titles, Chapters, and Sections . . . . . . . .Cross References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Footnotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Emphasized Words . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Environments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.11.1 Itemize, Enumerate, and Description2.11.2 Flushleft, Flushright, and Center . .2.11.3 Quote, Quotation, and Verse . . . .2.11.4 Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2.11.5 Printing Verbatim . . . . . . . . . .2.11.6 Tabular . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Floating Bodies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Protecting Fragile Commands . . . . . . . .3 Typesetting Mathematical Formulae3.1 General . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.2 Grouping in Math Mode . . . . . . . . . . .3.3 Building Blocks of a Mathematical Formula3.4 Math Spacing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.5 Vertically Aligned Material . . . . . . . . .3.6 Phantoms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.7 Math Font Size . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.8 Theorems, Laws, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.9 Bold Symbols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3.10 List of Mathematical Symbols . . . . . . . 9394144.4545474751525454555758

CONTENTSix4 Specialities4.1 Including Encapsulated PostScript Graphics4.2 Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.3 Indexing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.4 Fancy Headers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.5 The Verbatim Package . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.6 Downloading and Installing LATEX Packages . .4.7 Working with pdfLATEX . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.7.1 PDF Documents for the Web . . . . . .4.7.2 The Fonts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.7.3 Using Graphics . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.7.4 Hypertext Links . . . . . . . . . . . . .4.7.5 Problems with Links . . . . . . . . . . .4.7.6 Problems with Bookmarks . . . . . . . .4.8 Creating Presentations with pdfscreen . . . . .5 Producing Mathematical Graphics5.1 Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2 The picture Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.1 Basic Commands . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.2 Line Segments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.3 Arrows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.4 Circles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.5 Text and Formulas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.6 The \multiput and the \linethickness command . .5.2.7 Ovals. The \thinlines and the \thicklines command5.2.8 Multiple Use of Predefined Picture Boxes . . . . . . .5.2.9 Quadratic Bézier Curves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.10 Catenary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5.2.11 Rapidity in the Special Theory of Relativity . . . . . .5.3 XY-pic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6 Customising LATEX6.1 New Commands, Environments and Packages6.1.1 New Commands . . . . . . . . . . . .6.1.2 New Environments . . . . . . . . . . .6.1.3 Extra Space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.1.4 Commandline LATEX . . . . . . . . . .6.1.5 Your Own Package . . . . . . . . . . .6.2 Fonts and Sizes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.2.1 Font Changing Commands . . . . . . .6.2.2 Danger, Will Robinson, Danger . . . .6.2.3 Advice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.3 Spacing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192939495959999100101101102103103103106106107

xCONTENTS6.46.56.66.76.3.1 Line Spacing . . . . .6.3.2 Paragraph Formatting6.3.3 Horizontal Space . . .6.3.4 Vertical Space . . . . .Page Layout . . . . . . . . . .More Fun With Lengths . . .Boxes . . . . . . . . . . . . .Rules and Struts . . . . . . .107107108109110112113115Bibliography117Index119

List of Figures1.11.2A Minimal LATEX File. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Example of a Realistic Journal Article. . . . . . . . . . . . . .774.14.2Example fancyhdr Setup. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Example pdfscreen input file . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70816.16.2Example Package. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103Page Layout Parameters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

List of Tables1.11.21.31.4Document Classes. . . . . . . . . . . .Document Class Options. . . . . . . .Some of the Packages Distributed withThe Predefined Page Styles of LATEX. . . . . . . .LATEX. . . .91012122.12.22.32.42.52.62.7A bag full of Euro symbols . . . . . .Accents and Special Characters. . . .Preamble for Portuguese documents.Special commands for French. . . . .German Special Characters. . . . . .Bulgarian, Russian, and Ukrainian .Float Placing Permissions. . . . . . 3.123.133.143.153.163.173.183.19Math Mode Accents. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Lowercase Greek Letters. . . . . . . . . . . .Uppercase Greek Letters. . . . . . . . . . .Binary Relations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Binary Operators. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .BIG Operators. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Arrows. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Delimiters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Large Delimiters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Miscellaneous Symbols. . . . . . . . . . . . .Non-Mathematical Symbols. . . . . . . . . .AMS Delimiters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .AMS Greek and Hebrew. . . . . . . . . . . .AMS Binary Relations. . . . . . . . . . . . .AMS Arrows. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .AMS Negated Binary Relations and Arrows.AMS Binary Operators. . . . . . . . . . . .AMS Miscellaneous. . . . . . . . . . . . . .Math Alphabets. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .585858595960606060616161616262636364644.1Key Names for graphicx Package. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .66.

xivLIST OF TABLES4.2Index Key Syntax Examples. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6.16.26.36.46.5Fonts. . . . . . . . . .Font Sizes. . . . . . . .Absolute Point Sizes inMath Fonts. . . . . . .TEX Units. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Standard Classes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .69104104105105109

Chapter 1Things You Need to KnowThe first part of this chapter presents a short overview of the philosophy andhistory of LATEX 2ε . The second part focuses on the basic structures of a LATEXdocument. After reading this chapter, you should have a rough knowledge ofhow LATEX works, which you will need to understand the rest of this book.1.11.1.1The Name of the GameTEXTEX is a computer program created by Donald E. Knuth [2]. It is aimedat typesetting text and mathematical formulae. Knuth started writing theTEX typesetting engine in 1977 to explore the potential of the digital printingequipment that was beginning to infiltrate the publishing industry at thattime, especially in the hope that he could reverse the trend of deterioratingtypographical quality that he saw affecting his own books and articles. TEXas we use it today was released in 1982, with some slight enhancements addedin 1989 to better support 8-bit characters and multiple languages. TEX isrenowned for being extremely stable, for running on many different kinds ofcomputers, and for being virtually bug free. The version number of TEX isconverging to π and is now at 3.14159.TEX is pronounced “Tech,” with a “ch” as in the German word “Ach” orin the Scottish “Loch.” In an ASCII environment, TEX becomes TeX.1.1.2LATEXLATEX is a macro package that enables authors to typeset and print theirwork at the highest typographical quality, using a predefined, professionallayout. LATEX was originally written by Leslie Lamport [1]. It uses the TEXformatter as its typesetting engine. These days LATEX is maintained by FrankMittelbach.

2Things You Need to KnowLATEX is pronounced “Lay-tech” or “Lah-tech.” If you refer to LATEX inan ASCII environment, you type LaTeX. LATEX 2ε is pronounced “Lay-techtwo e” and typed LaTeX2e.1.21.2.1BasicsAuthor, Book Designer, and TypesetterTo publish something, authors give their typed manuscript to a publishingcompany. One of their book designers then decides the layout of the document (column width, fonts, space before and after headings, . . . ). The bookdesigner writes his instructions into the manuscript and then gives it to atypesetter, who typesets the book according to these instructions.A human book designer tries to find out what the author had in mindwhile writing the manuscript. He decides on chapter headings, citations,examples, formulae, etc. based on his professional knowledge and from thecontents of the manuscript.In a LATEX environment, LATEX takes the role of the book designer anduses TEX as its typesetter. But LATEX is “only” a program and thereforeneeds more guidance. The author has to provide additional information todescribe the logical structure of his work. This information is written intothe text as “LATEX commands.”This is quite different from the WYSIWYG1 approach that most modernword processors, such as MS Word or Corel WordPerfect, take. With theseapplications, authors specify the document layout interactively while typingtext into the computer. They can see on the screen how the final work willlook when it is printed.When using LATEX it is not normally possible to see the final output whiletyping the text, but the final output can be previewed on the screen afterprocessing the file with LATEX. Then corrections can be made before actuallysending the document to the printer.1.2.2Layout DesignTypographical design is a craft. Unskilled authors often commit seriousformatting errors by assuming that book design is mostly a question ofaesthetics—“If a document looks good artistically, it is well designed.” Butas a document has to be read and not hung up in a picture gallery, the readability and understandability is much more important than the beautifullook of it. Examples: The font size and the numbering of headings have to be chosen to makethe structure of chapters and sections clear to the reader.1What you see is what you get.

1.2 Basics The line length has to be short enough not to strain the eyes of thereader, while long enough to fill the page beautifully.With WYSIWYG systems, authors often generate aesthetically pleasingdocuments with very little or inconsistent structure. LATEX prevents suchformatting errors by forcing the author to declare the logical structure of hisdocument. LATEX then chooses the most suitable layout.1.2.3Advantages and DisadvantagesWhen people from the WYSIWYG world meet people who use LATEX, theyoften discuss “the advantages of LATEX over a normal word processor” or theopposite. The best thing you can do when such a discussion starts is to keepa low profile, since such discussions often get out of hand. But sometimesyou cannot escape . . .So here is some ammunition. The main advantages of LATEX over normalword processors are the following: Professionally crafted layouts are available, which make a documentreally look as if “printed.” The typesetting of mathematical formulae is supported in a convenientway. Users only need to learn a few easy-to-understand commands that specify the logical structure of a document. They almost never need totinker with the actual layout of the document. Even complex structures such as footnotes, references, table of contents, and bibliographies can be generated easily. Free add-on packages exist for many typographical tasks not directlysupported by basic LATEX. For example, packages are available to include PostScript graphics or to typeset bibliographies conforming toexact standards. Many of these add-on packages are described in TheLATEX Companion [3]. LATEX encourages authors to write well-structured texts, because thisis how LATEX works—by specifying structure. TEX, the formatting engine of LATEX 2ε , is highly portable and free.Therefore the system runs on almost any hardware platform available.LATEX also has some disadvantages, and I guess it’s a bit difficult for me tofind any sensible ones, though I am sure other people can tell you hundreds;-)3

4Things You Need to Know LATEX does not work well for people who have sold their souls . . . Although some parameters can be adjusted within a predefined document layout, the design of a whole new layout is difficult and takes alot of time.2 It is very hard to write unstructured and disorganized documents. Your hamster might, despite some encouraging first steps, never beable to fully grasp the concept of Logical Markup.LATEX Input Files1.3The input for LATEX is a plain ASCII text file. You can create it with anytext editor. It contains the text of the document, as well as the commandsthat tell LATEX how to typeset the text.1.3.1Spaces“Whitespace” characters, such as blank or tab, are treated uniformly as“space” by LATEX. Several consecutive whitespace characters are treatedas one “space.” Whitespace at the start of a line is generally ignored, and asingle line break is treated as “whitespace.”An empty line between two lines of text defines the end of a paragraph.Several empty lines are treated the same as one empty line. The text belowis an example. On the left hand side is the text from the input file, and onthe right hand side is the formatted output.It does not matter whether youenter one or severalspacesafter a word.It does not matter whether you enter one orseveral spaces after a word.An empty line starts a new paragraph.An empty line starts a newparagraph.1.3.2Special CharactersThe following symbols are reserved characters that either have a specialmeaning under LATEX or are not available in all the fonts. If you enter themdirectly in your text, they will normally not print, but rather coerce LATEXto do things you did not intend.#2 % &{} \Rumour says that this is one of the key elements that will be addressed in the upcomingEX3 system.LAT

1.3 LATEX Input Files5As you will see, these characters can be used in your documents all thesame by adding a prefix backslash:\# \ \% \ {} \& \ \{ \} \ {}# %ˆ& {} The other symbols and many more can be printed with special commandsin mathematical formulae or as accents. The backslash character \ can notbe entered by adding another backslash in front of it (\\); this sequence isused for line breaking.31.3.3LATEX CommandsLATEX commands are case sensitive, and take one of the following two formats: They start with a backslash \ and then have a name consisting ofletters only. Command names are terminated by a space, a number orany other ‘non-letter.’ They consist of a backslash and exactly one non-letter.LATEX ignores whitespace after commands. If you want to get a spaceafter a command, you have to put either {} and a blank or a special spacingcommand after the command name. The {} stops LATEX from eating up allthe space after the command name.I read that Knuth divides thepeople working with \TeX{} into\TeX{}nicians and \TeX perts.\\Today is \today.I read that Knuth divides the people workingwith TEX into TEXnicians and TEXperts.Today is 4th April 2004.Some commands need a parameter, which has to be given between curlybraces { } after the command name. Some commands support optional parameters, which are added after the command name in square brackets [ ].The next examples use some LATEX commands. Don’t worry about them;they will be explained later.You can \textsl{lean} on me!You can lean on me!Please, start a new lineright here!\newlineThank you!Please, start a new line right here!Thank you!3Try the \backslash command instead. It produces a ‘\’.

6Things You Need to Know1.3.4CommentsWhen LATEX encounters a % character while processing an input file, it ignoresthe rest of the present line, the line break, and all whitespace at the beginningof the next line.This can be used to write notes into the input file, which will not showup in the printed version.This is an % stupid% Better: instructive ---example: Supercal%ifragilist%icexpialidociousThis is an example: SupercalifragilisticexpialidociousThe % character can also be used to split long input lines where no whitespace or line breaks are allowed.For longer comments you could use the comment environment providedby the verbatim package. This means, to use the comment environment youhave to add the command \usepackage{verbatim} to the preamble of yourdocument.This is another\begin{comment}rather stupid,but helpful\end{comment}example for embeddingcomments in your document.This is another example for embedding comments in your document.Note that this won’t work inside complex environments, like math forexample.1.4Input File StructureWhen LATEX 2ε processes an input file, it expects it to follow a certain structure. Thus every input file must start with the command\documentclass{.}This specifies what sort of document you intend to write. After that, youcan include commands that influence the style of the whole document, oryou can load packages that add new features to the LATEX system. To loadsuch a package you use the command\usepackage{.}When all the setup work is done,4 you start the body of the text withthe command4The area between \documentclass and \begin{document} is called the preamble.

1.5 A Typical Command Line Session\begin{document}Now you enter the text mixed with some useful LATEX commands. Atthe end of the document you add the\end{document}command, which tells LATEX to call it a day. Anything that follows thiscommand will be ignored by LATEX.Figure 1.1 shows the contents of a minimal LATEX 2ε file. A slightly morecomplicated input file is given in Figure 1.2.1.5A Typical Command Line SessionI bet you must be dying to try out the neat small LATEX input file shownon page 7. Here is some help: LATEX itself comes without a GUI or fancybuttons to press. It is just a program that crunches away at your input file.Some LATEX installations feature a graphical front-end where you can click\documentclass{article}\begin{document}Small is beautiful.\end{document}Figure 1.1: A Minimal LATEX File.\documentclass[a4paper,11pt]{article}% define the title\author{H. Partl}\title{Minimalism}\begin{document}% generates the title\maketitle% insert the table of contents\tableofcontents\section{Some Interesting Words}Well, and here begins my lovely article.\section{Good Bye World}\ldots{} and here it ends.\end{document}Figure 1.2: Example of a Realistic Journal Article.7

8Things You Need to KnowLATEX into compiling your input file. On other systems there might be sometyping involved, so here is how to coax LATEX into compiling your input fileon a text based system. Please note: this description assumes that a workingLATEX installation already sits on your computer.51. Edit/Create your LATEX input file. This file must be plain ASCII text.On Unix all the editors will create just that. On Windows you mightwant to make sure that you save the file in ASCII or Plain Text format.When picking a name for your file, make sure it bears the extension.tex.2. Run LATEX on your input file. If successful you will end up with a .dvifile. It may be necessary to run LATEX several times to get the tableof contents and all internal references right. When your input file hasa bug LATEX will tell you about it and stop processing your input file.Type ctrl-D to get back to the command line.latex foo.tex3. Now you may view the DVI file. There are several ways to do that.You can show th

graphics. It introduces creation of PDF documents with pdfLATEX and presents some handy extension packages. Chapter 5 shows how to use LATEX for creating graphics. Instead of draw-ing a picture with some graphics program, saving it to a file and then including it into LATEX you describe the picture and have LATEX draw it for you.