Transcription

FOOD & WATER W ATCH ! IOWA FARMERS UNION ! MISSOURI RURAL CRISIS CENTER ! NATIONAL FARMERS U NIONThe Anticompetitive Effects of the Proposed JBSCargill Pork Packing AcquisitionJuly 2015

ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITION1I. IntroductionThe proposed acquisition of Cargill Pork(Cargill) by JBS S.A. (JBS) wouldsignificantly reduce competition in the hogprocessingandslaughterindustry,disadvantaging hog producers, wholesalepork buyers and, ultimately, consumers. Thescale and scope of the proposed acquisitionwarrant substantial scrutiny by the U.S.Department of Justice.JBS and Cargill are already two of thelargest meatpackers in the United States andglobally. In the United States, the combinedfirms sold 59 billion worth of meatproducts in 2014 making them the secondand third largest meat processing firmsbehind Tyson Foods.1 Brazil-based JBS isthe world’s largest meat company and thesecond largest beef packer, second largestpoultry processor and third largest porkpacker in the United States.2 Cargill is thelargest privately held company in the UnitedStates and the third largest meat processor inthe United States.3 The proposed acquisitionalso would mean that the top two porkpacking firms — Smithfield and JBS — arecontrolled by foreign companies.4The proposed 1.45 billion acquisitionwould join the third and fourth largest porkpacking companies and the post-acquisition1“National Provisioner’s Top 100.” National Provisioner.May 2015 at 30.2“JBS to purchase U.S. Cargill pork assets for 1.45billion.” Reuters. July 1, 2015; Magalhaes, Luciana. “WithCargill purchase, Brazil’s JBS poised to become No. 2 porkproducer in U.S.” Wall Street Journal. July 2, 2015; “2014top poultry companies.” Watt Poultry USA. March 2014 at18.3Murphy, Andrea. “Top 20 largest private companies of2014.” Forbes. November 5, 2014; Clyma, Kimberlie.“Leaders of the pack.” Meat and Poultry. March 2015 at 16,22.4In 2013, Smithfield was purchased by ShuanghuiInternational Holdings Ltd. (now WH Group) for 4.7billion. Tadena, Nathalie. “Smithfield Shareholdersapprove Shuanghui deal.” Wall Street Journal. September24, 2013.JBS would surpass Tyson Foods to becomethe second largest hog processor in thecountry behind Smithfield. 5 It also wouldcreate a considerably more verticallyintegrated JBS. The deal includes Cargill’stwo pork slaughter and processing plants(located in Ottumwa, Iowa and Beardstown,Illinois), five feed mills (located in Missouri,Arkansas, Iowa, and Texas), along with fourhog production facilities (located inArkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas).6 Cargill’shog production facilities were the eighthlargest in the country in 2014, with 161,000sows.7The merger extends JBS’ long-term effort tobecome the dominant protein company ineach market. The company has grown intothe largest meat processor in the worldprimarily through large acquisitions. JBShas “a very aggressive growth strategy” andgrowth through acquisitions is “in [thecompany’s] DNA.” 8 The proposed t in the long-term growth of[JBS’] domestic and global pork businessanddemonstrates[thecompany’s]commitment to the U.S. livestock sector.”9The proposed merger would enable JBS togrow to become a more dominant and morevertically integrated meat manufacturer andviolates the Clayton Act’s prohibitionagainst mergers that may “substantially to5JBS USA. [Press release]. “JBS USA Pork agrees topurchase Cargill pork business.” July 1, 2015; Magalhaes(2015); National Pork Board. “Pork Stats 2014.” 2014 at 22.6JBS USA (2015).7“Top 25 Pork Powerhouses.” Successful Farming. 2015.8Runyon, Luke. “Inside the world’s largest food companyyou’ve never heard of.” KUNC Community Radio forNorthern Colorado. June 26, 2015; Blankfield, Keren.“JBS: the story behind the world’s biggest meat producer.”Forbes. April 21, 2011.9Gylan, Georgi. “JBS to make further acquisition withCargill pork business.” Global Meat News. July 2, 2015.

2ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONlessen competition, or tend to create amonopoly.” 10 The proposed merger runsafoul of the U.S. Department of Justice’smerger guidance stating “[m]ergers shouldnot be permitted to create, enhance, orentrench market power or to facilitate itsexercise.”11Rapid consolidation in the food andagriculture sectors has been of risingconcern to farmers, consumers and federalregulators. Since the economy began torecover from the recession, the pace ofmergers has accelerated and threatens toincrease concentration in the already overconsolidated food and agriculture sectors. In2014, there were more than more than 300food and beverage mergers and acquisitionsvalued over 120 billion. 12 The proposedacquisition contributes to the growing sizeand market power of the top meat andpoultry processors that has had tremendousripple effects across the food chain. Mergersand acquisitions in one portion of the foodchain are used to justify reverberatingmergers up and down the agribusiness, foodmanufacturing and retailing sectors.Only robust antitrust enforcement canprotect consumers and farmers fromanticompetitive combinations and practices.A May 2012 Department of Justice report“stressed the importance of vigorousantitrust enforcement” and detailed the waysthat anticompetitive mergers and conductcan harm farmers, consumers and others.131015 U.S.C. §18.U.S. Department of Justice/Federal Trade Commission(DoJ/FTC). “Horizontal Merger Guidelines.” August 19,2010 at 2.12Harris Williams & Co. “Food and Beverage IndustryUpdate.” January 2015 at 11; de la Merced, Michael. “Dealmakers notched nearly 3.5 trillion worth in ’14, best in 7years.” New York Times. January 1, 2015.13U.S. Department of Justice. “Competition andAgriculture: Voices from the Workshops on Agricultureand Antitrust Enforcement in our 21st Century Economy.”May 2012 at 2.11As President Barack Obama observed in his2013 Inaugural Address “a free market onlythrives when there are rules to ensurecompetition and fair play.”14The proposed acquisition creates asubstantially more concentrated hogslaughter market and would give JBSCargill the capacity and incentive toprofitably exert this market power over itsrivals, farmers and consumers. It wouldsignificantly increase the company’s buyerpower over farmers, both nationally and inthe Midwest regions surrounding eachfacility (Section II). It would increase theanticompetitive vertical integration in theindustry, reducing options for farmersselling hogs on the open market, deliveringhogs under contract or raising hogs underproduction contracts (Section III). It wouldalso further concentrate the market forwholesale pork products, raising prices forretailers, further processing companies andfoodservice outlets (Section IV). Ultimatelythese price increases would be passed ontoconsumers at the grocery store (Section V).The combined increase in monopsonymarket power over hog producers and theincrease in monopoly market power overconsumers acts as a transfer of economicwelfare from both farmers and eaters towhat would become the second largest porkpacker in the United States.The Department of Justice must oppose theearly termination of the antitrust review andissue a second request under the Hart-ScottRodino Act to fully examine theanticompetitive and anti-consumer impactsof the proposed acquisition. 15 We believethe Department of Justice should ultimatelyenjoin this merger.14President Barack Obama. 2013 Inaugural Address.January 21, 2013.1515 U.S.C. §18(e).

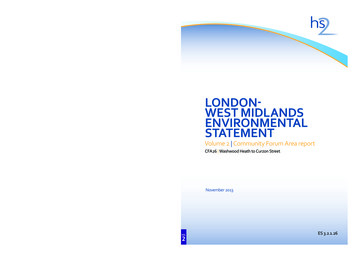

ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITION3II. Proposed Acquisition Would Exacerbate Buyer Power Over Hog FarmersThe proposed acquisition would increase thebuyer power concentration over hog farmersin an already consolidated hog slaughter andprocessing sector. Over the past few decades,the U.S. pork packing and processingindustry has gained a dominant position overhog farmers through mergers, acquisitionsand the emergence of contractualrelationships between packers and producers.The appropriate market to measure porkpacker buyer power is live slaughter hogs(gilts and barrows) within the appropriateregional markets encompassing captive drawareas (see below for analyses of severalregions of concern).States, and well above levels generallyconsidered to elicit non-competitivebehavior and result in adverse economicperformance,” according to Oklahoma StateUniversity professor Clement Ward.18 Thishorizontal consolidation and verticalintegration in the pork packing industry hascontributed significantly to the decline in thenumber of hog farms. The United States haslost 150,000 hog operations — about 70percent — between 1993 and 2012.19National concentration in the hog slaughterindustry has nearly doubled over the pastthree decades as mergers significantlyreduced the number of competitors andincreased market concentration. 20 In 1982,the four largest firms slaughtered one out ofthree hogs (35.8 percent) nationally. ByCompetition among processors is critical forthe thousands of farmers trying to earn aliving selling their hogs. In 2013, 111million hogs were purchased ata cost of over 20 billion.16 tio'74% 2014,commercialhogslaughter was 106.9 million65% 65% 65% 64% 64% 64% 64% 63% 63% 63% head. 17 28.6 million of them61% 57% 57% 57% 56% were in Iowa alone.54% 54% 50% 46% 44% 44% 44% 42% 40% 34% 34% 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2014 2015* The hog production sector ishorizontally concentrated (onlya few companies buy, slaughterand process the majority ofhogs) and vertically integrated(pork packers have tightcontractual relationships withhog producers throughout levels are among the highest ofany industry in the UnitedSource: USDA GIPSA, National Pork Board; 2015 accounts for proposed JBSJCargill acquisition 16National Pork Producers Council. “The importance oftrade to U.S. agriculture.” Testimony before the AgricultureCommittee. United States House of Representatives. March18, 2015 at 2.17U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). NationalAgricultural Statistical Service (NASS). “LivestockSlaughter 2014 Summary.” April 2015 at 6, 45.18Ward, Clement E. “A review of causes for andconsequences of economic concentration in the U.S.meatpacking industry.” Current. No. 3. 2002 at 1.19USDA NASS. “Hogs—Operations with Inventory.”Available at quickstats.nass.usda.gov, accessed July 2014.20Ward (2002) at 5.

4ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONTable 1: National Pork Packing ConcentrationSlaughter Capacity (head/day)Market SharePost-JBSCargill201220132014Post-Merger son 3%Cargill 2611,2721,277HHI-All1,4121,4181,42236,800Δ% 14.2%Source: Analysis of National Pork Board data.2014 that figure nearly doubled, as the fourbiggest companies slaughtered two out ofthree hogs (65.5 percent) (see Figure 1).21Since the 1990s, Smithfield Foods, thenation’s largest pork processor, absorbedcompetitors including John Morrell,Premium Standard Farms and Farmland,which had facilities and operationsthroughout the Midwest. 22 In 2001, TysonFoods bought IBP, which had four hogpacking plants in reasethenationalconcentration in pork packing. If theproposed acquisition were approved, the topfour pork packers would slaughter three outof four hogs (74.0 percent), a 13.0 percentincrease (see Table 1). The proposedacquisition would represent the largestincrease in pork packer concentration in thepast 25 years, significantly larger than whenSmithfield purchased Farmland in 2003.24The proposed acquisition would create amoderately concentrated national hog packermarket, with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index(HHI) increase over 200 with a national HHIof over 1,600 that “potentially raise[s]significant competitive concerns [that] oftenwarrant scrutiny.” 25 The proposedacquisition would make the three largestpork packers much closer in size andconsiderably larger than the next largestpackers. Prior to the proposed deal, JBS andCargill were only slightly larger than thenext largest rival, Hormel (with 11.6, 8.7and 8.5 percent of the national slaughtercapacity, respectively). After the proposeddeal, JBS-Cargill would be twice as large asHormel and about four times larger than thefifth and sixth largest firms (Triumph andSeaboard, each with under 5 percent of thenational slaughter capacity).21USDA. Grain Inspection, Packers and StockyardsAdministration. “Packers and Stockyards Statistical Report:1997 Reporting Year.” GIPSA SR-99-1. June 1999 at Table31; USDA GIPSA. “2013 Annual Report Packers andStockyards Program.” March 2014 at Table 14 at 31;National Pork Board (2014) at 22.22Smithfield Foods. SEC Form 10-K. August 2, 1999 at 2;Smithfield Foods. Annual Report 2004. 2004 at 6; NationalPork Board (2009–2012) at 96.23Tyson Foods. 2001 Annual Report. 2001 at 22; NationalPork Board. “Pork Quick Facts.” 2012 at 96.24The proposed acquisition increases the four-firmconcentration ratio by 10 percentage points, a nearly 16percent relative increase. The 2003 Smithfield-Farmlandmerger was associated with a 7 percentage point increase inthe four-firm concentration ratio, a relative increase of 13percent. John Morrell. [Press release]. “John Morrellpresident urges Senators to clear Smithfield-FarmlandFoods transaction.” July 23, 2003.25DoJ/FTC (2010) at 19.

ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONA. Buyer power extracts value y strengthen monopsony buyerpower and enable JBS-Cargill to exerciseunilateral and coordinated market power todepress hog prices paid to producers andfarmers. The rising concentration in the porkpacking industry increases buyer powersignificantly and gives firms more leverageover farmer suppliers. This power dynamicallows processors to exercise considerablecontrol over farmers, lower the prices theypay for hogs and more easily collude withother packers, either tacitly or expressly.Pork packers and processors are thegatekeepers of the hog and pork sector.These firms can source hogs from thousandsof different farmers but the farmers sell mostof their hogs to only a handful of firms.Farmers generally sell all their marketablehogs to one buyer, which gives pork packerstremendousbargainingpoweroverfarmers.26 The decline in the number of hogbuyers has left fewer selling options for hogproducers, which puts them under increasedpressure to take whatever price they can get,even if it does not cover their costs.Consolidation has made it easier for porkpackers to tacitly collude to drive downprices. All pork packers benefit when theprices they pay to producers are low, sothere is little incentive to compete bybidding up prices and every incentive toexercise tacit coordinated market power.Buyers can withhold or lower their offers forhogs with little fear of competitors trying topay more for the product.27 In some cases,there is only one buyer at hog auctions as a26Carstensen, Peter C. University of Wisconsin LawSchool. Statement Prepared for the Workshop on MergerEnforcement. February 17, 2004 at 13.27Ibid. at 4.5resultofmarketconsolidation.Consolidation also gives the pork packers asignificant informational advantage overfarmers because they regularly purchaselarge volumes of hogs and are moreknowledgeable about prevailing marketconditions. 28 In 1990, when pork packerconcentration levels were only half whatthey are today, a study found that the hogpacking sector exhibited market buyerpower that was “not statistically differentfrom a collusive oligopsony.”29The perishability of most agriculturalproducts significantly exacerbates theimpact of market concentration and givesbuyers unique leverage over farmers. 30Buyers can impose lower prices orunfavorable terms on farmers who must sellperishable products.31 Finished livestock areonly at their ideal slaughter weight for a fewweeks.32 Market hogs are slaughtered at anideal weight of 265 pounds. 33 If farmerscannot find decent prices for their hogswhen they reach market weight, they mustchoose between bearing the cost ofoverfeeding their hogs while they search foralternate buyers and/or receiving lessfavorable prices.28Schroeder, Ted C. and James Mintert. “Market Hog PriceDiscovery: Barriers and Opportunities.” Paper presented atthe National Pork Producers Council’s National PorkSummit. Kansas City, Missouri. December 10, 1999 at 3.29Azzam, A.M. and E. Pagoulatos. “Testing oligopolisticand oligopsonistic behavior: An application to the U.S.meat-packing industry.” Journal of Agricultural Economics.Vol. 41, Iss. 3. 1990 at 368.30Domina, David and C. Robert Taylor. Organization forCompetitive Markets. “The Debilitating Effects ofConcentration in Markets Affecting Agriculture.”September 2009 at 8.31Carstensen (2004) at 22.32Taylor, C. Robert. Auburn University. “The Many Facesof Power in the Food System.” Presentation at the DoJ/FTCWorkshop on Merger Enforcement. February 17, 2004 at 3.33USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. “2012 AnnualMeat Trade Review.” 2012 at 3.

6ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK 'Four/Firm'Concentration'(real 2014 dollars) 120 70% 60% 100 50% 80 40% 60 30% percent of the national hog marketbefore the proposed merger (11.6and 8.7 percent, respectively), butthe proposed acquisition wouldgive JBS-Cargill more than onefifth of the national hog market(20.3 percent), giving the postmerger firm considerably moreleverage over hog farmers andcapacity to disadvantage farmersin price negotiations and contracts.Mergers and acquisitions havemade the remaining pork packerssignificantly larger and helped to 20 10% drive medium-sized firms out ofbusiness. Since 2003, six hog J 0% slaughter plants closed in the1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 Midwest, reducing the total dailyReal Hog Price ( 2014/CWT, left axis) CRJ4 (right axis) market for hogs by 22,500 headSource: USDA NASS; USDA GIPSA, BLS — the equivalent of eliminating36TriumphFoods.ThisBuyer power is similar to seller power, butconsolidation has reduced options and pricesthe power dynamics between pork packersfor farmers. A 1999 economic model bybuying hogs is different from thePurdue University estimated that amonopolistic power exerted by foodmarketplace with 20 equally sized porkcompanies on retail consumers. Buyers havepackers (akin to the national market in thedifferent market incentives and operate inlate 1980s) would pay about 5 percent lessdifferent marketplaces, and the limitationsthan a perfectly competitive marketplace; aon buyer-side competition can be differentmarketplace with eight firms would pay 18than for sellers. 34 Consolidated buyerpercent less; and if there were only fourmarkets and large single-firm buyer marketfirms, they would pay 28 percent less than ashares can be more distorting andperfectly competitive market.37 The authorsanticompetitive than seller markets.concluded, “We have shown that greaterconsolidation in the meat packing andBuyers can exert more market power overprocessing industry creates a markdowntheir suppliers with a smaller share of theeffect on the prices farmers receive for livepurchasing market than sellers can exercise.animals.”38Buyers can potentially exert unilateraldominance over suppliers with control ofless than ten percent of the purchasingmarket. 35 JBS and Cargill held about 10 40 20% 36National Pork Board. “Pork Facts.” 2013 at 101.Paarlberg, Philip et al. Department of AgriculturalEconomics, Purdue University. “Structural Change andMarket Performance in Agriculture: Critical Issues andConcerns About Concentration in the Pork Industry.” StaffPaper 99-14. October 1999 at 6 to 7.38Ibid. at 8.3734Carstensen (2004) at 3.Foer, Albert A. American Antitrust Institute. “Mr.Magoo Visits Wal-Mart: Finding the Right Lens forAntitrust.” Working Paper No. 06-07. November 30, 2006at 5.35

ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONAs market concentration has increased, thereal price farmers receive for their hogs hasdeclined (see Figure 2). Between 1988 and2012, the market share of the top four porkpackers nearly doubled from 34 percent to64 percent. 39 Over the same period, realfarmgate hog prices fell by about one-fifth(18 percent), from 84 per hundredweight inthe period 1988 to 1992 to 68 perhundredweight between 2010 and 2014(measured in inflation adjusted 2014dollars). 40 The proposed acquisition wouldonly worsen this trend by strengtheningJBS-Cargill’s overall leverage over hogfarmers and strengthening its unilateral andcoordinated market power to push down onhog prices. Even if the proposed acquisitioncontributed to small but significantreductions in the price farmers receive forhogs, it could have a significant impact onwhether hog producers are economicallyviable or are forced to exit farming.41Farmers would be largely unable to avoidthese price cuts. The livelihood of hogfarmers depends on their ability to sell theirhogs to buyers offering the best prices thatenable them to pay for all of the costs thatthey incur, including production andtransportation. 42 Hog farming requiressignificant investment, infrastructure, andtime considerations that are unique to thoseanimals. Hog farmers cannot easily switch39USDA GIPSA. “Packers and Stockyards StatisticalReport: 1996 Reporting Year.” SR-98-0. October 1998 at48; USDA GIPSA. “Packers and Stockyards StatisticalReport: 1995 Reporting Year.” SR-97-1. 1997 at Table 31;USDA GIPSA. “Packers and Stockyards Annual Report2010.” 2010 at 45; USDA GIPSA. “Statistical Report 2002.”2002 at Table 30; USDA GIPSA. “Packers and StockyardsAnnual Report 2013.” 2013 at 31.40USDA NASS. Quickstats. “Hogs—Price Received,Measured in /CWT.” Available atquickstats.nass.usda.gov, accessed July 2015; Real dollardeflator calculated with U.S. Department of Labor, Bureauof Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator. Available atbls.gov/data/inflation calculator.htm, accessed July 2015.41Ward (2002) at 2 and 19.42See Complaint at 6. U.S. v. Cargill, Inc. and ContinentalGrain Co. (D.D.C. 1999) (No. 99-1875).7to another animal type or a commodity cropin order to avoid a small farmgate pricedecrease.Nor would it be likely that new pork packerswould enter the market to capitalize on JBSCargill’s exercise of market power bypaying slightly more for hogs or chargingslightly less for pork. New entry into porkprocessing is costly and time consuming.Construction of a large-scale slaughterfacility would take hundreds of millions ofdollars and the additional planning, designand permitting costs are substantial. Arecent expansion of Cargill’s Ottumwafacility alone cost the company 25million. 43 Building a facility from scratchwould likely be considerably more, and if afirm wanted to enter the market throughpurchasing an already completed facility,this current acquisition shows how muchthat can potentially cost. As the Departmentof Justice noted in its complaint against theCargill-Continental grain merger, thesefactors make it unlikely that the “exercise ofmarket power will be prevented by newentry [ ] or by any other countervailingcompetitive force.”44B. Midwestern hog-buyinggeographic marketNational concentration measurements canconceal much higher market concentrationthat farmers face at the regional or locallevel.45 Mergers can increase market powerin regional markets where the merged firmcan extract even minor price concessions43Cargill. [Press release]. “Cargill 29 million Hedrick,Iowa, pork business feed mill dedication set for May 12.”May 4, 2012.44See Complaint at 12. U.S. v. Cargill, Inc. and ContinentalGrain Co. (D.D.C. 1999) (No. 99-1875).45MacDonald, James M. and William D. McBride. USDAEconomic Research Service (ERS). “The Transformationof U.S. Livestock Agriculture: Scale, Efficiency, and Risks.”EIB-43. January 2009 at 25.

8ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONthat sellers cannot avoid. 46 Pork packingplants are generally located near hogproduction areas to reduce livestocktransportation costs from the farm to theslaughterhouse.47 The majority of U.S. hogsare produced in the Midwestern corn belt,where transportation costs and access tocorn and soymeal feed ingredients is thelowest.48The proposed JBS-Cargill acquisitionincludes five pork packing plants, a JBSplant and a Cargill plant in Iowa, a JBS plantin Minnesota, a Cargill plant in Illinois and aJBS plant in Kentucky, spanning the hogproducing region from Indiana to Minnesota,Nebraska and Missouri (see Map 1).49 Thetransportation cost and hog weight“shrinkage” limit the distance that hogs canbe transported in order to reach a potentialcompeting buyer’s processing facility. 50Hogs are shipped on average 113 miles from46U.S. v. Cargill (2000) at 19.Muth, Mary K. et al. RTI International. “Pork Slaughterand Processing Sector Facility-Level Model.” Prepared forUSDA, Food Safety and Inspection Service. Contract No.53-3A94-02-12. June 2007 at 2–2.48RTI International. Prepared for USDA GIPSA. “GIPSALivestock and Meat Marketing Study: Volume 1: ExecutiveSummary and Overview – Final Report.” January 2007 at1–4.4749National Pork Board (2013) at 100; USDA NASS. 2012Census of Agriculture Atlas Maps. “Number of Farms with200 or More Hogs and Pigs: 2012.” 2014 at Map 12-M150.50See Complaint at 7. U.S. v. JBS. S.A. and National BeefPacking Co., LLC. (N.D. Ill. 2008) (No. 08-CV-05992).

ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONTable 2: Midwestern Hog Belt—Farms and Hog SalesStateHogFarmsStateFarmRank% ofFarmsHog Sales(head)StateSalesRank% 3,62049.20%131,604,491South DakotaKentuckyMidwestern Total27,558Source: USDA NASS 2012 Census of Agriculture.farm to slaughterhouse, with a standarddeviation of 96 miles.51 Almost all hogswould be shipped within two standarddeviations of the average, or about 300miles. 52The appropriate geographicmarkets to evaluate the proposed JBSCargill acquisitionare the markets delineated by theoverlapping draw areas of the JBS andCargill pork packing plants.In the overlapping 300-mile “draw areas”for the JBS and Cargill facilities, thesefacilities are two of a small number ofcompeting pork processing plants. Byacquiring Cargill’s facilities in these captivedraw areas, JBS would be in a position tounilaterally, or in coordination with the fewremaining competitors, depress prices paidto hog farmers because transportation costs51RTI International (2007) at 2–48.A 300-mile draw is also in line with the typicaltransportation distance to market beef cattle. See Sexton,Richard J. Department of Agricultural and ResourceEconomics, University of California Davis.“Industrialization and Consolidation in the U.S. FoodSector: Implications for Competition and Welfare.” WaughLecture, Agricultural & Applied Economics AssociationAnnual Meeting, Tampa, Florida. August 2, 2000 at 21.529would preclude producers fromselling to more distant buyersoutside the captive draw areas insufficient quantities to preventthe price decrease.53The JBS and Cargill plantscompete to source hogs with65.3%other large slaughter plants74.9%within this 300-mile draw. Thisarea includes the major pork93.4%packers in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa,122.0%Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska131.8%andSouthDakota.This190.5%Midwestern region encompasses200.5%the buyer market for hogs for the66.2%proposed acquisition based onlocations of the suppliers (hogfarmers),transportationlimitations and competitive landscape forhog purchases.54There are essentially two broad draw areaswithin this Midwestern hog and corn belt,the western draw of Iowa and surroundingstates and the eastern draw of Illinois andIndiana and the surrounding states. Thesestates represent half of the hog farms (49.2percent) and two-thirds of the hog sales(66.2 percent) in the United States (seeTable 2).55 The proposed acquisition reducesthe options for the nearly 28,000 hogproducers in both regions, substantiallyincreases horizontal concentration andincreases the monopsony buyer power ofpork packers, giving them more marketpower to depress the prices farmers receivefor their hogs. In this analysis, we examinethe Iowa pork packing market, the Iowa andsurrounding states market and the IllinoisIndiana and surrounding states market.53See Complaint at 8 and 12. U.S. v. Cargill, Inc. andContinental Grain Co. (D.D.C. 1999) (No. 99-1875).54DoJ/FTC (2010) at 13 to 14.55USDA NASS. 2012 Census of Agriculture data.

10ANITICOMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF PROPOSED JBS2CARGILL PORK ACQUISITIONTable 3: Pork Packing Concentration in IowaSlaughter Capacity (head/day)Market SharePost Merger ChangePost 01220132014Tyson Foods53,60053,700JBS-Swift18,500Cargill PorkPost JBSCargillΔ% rce: Analysis of National Pork Board data.These are imprecise but reasonable

living selling their hogs. In 2013, 111 million hogs were purchased at a cost of over 20 billion.16 In 2014, commercial hog slaughter was 106.9 million head.17 28.6 million of them were in Iowa alone. The hog production sector is horizontally concentrated (only a few companies buy, slaughter and process the majority of