Transcription

The Association BetweenSchool-Based Physical Activity,Including Physical Education,and Academic PerformanceU.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesCenters for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health PromotionDivision of Adolescent and School Healthwww.cdc.gov/HealthyYouthRevised Version — July 2010(Replaces April 2010 Early Release)

Acknowledgments:This publication was developed for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Adolescentand School Health (DASH) under contract #200-2002-00800 with ETR Associates.Suggested Citation:Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The association between school-based physical activity, including physicaleducation, and academic performance. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010.

TABLE OF CONTENTSExecutive Summary .5Introduction .8Methods10Conceptual Definitions .10Inclusion Criteria .10Identification of Studies that Met the Inclusion Criteria .11Classification of Studies .11Study Coding Process .12Data Analysis .13Results .14School-Based Physical Education Studies .16Recess Studies .19Classroom Physical Activity Studies .21Extracurricular Physical Activity Studies .2428Summary .Overall Findings .28Findings for Physical Activity by Context .29Findings by Gender, Other Demographic Characteristics, and Research Design .30Strengths and Limitations of Review .30Implications for Future Research or Evaluation .31Implications for Schools .32References .34Appendices .39Appendix A: Database Search Terms .39Appendix B: Coding Sheet .41Appendix C: Glossary of Research Design Terms .51Appendix D: School-Based Physical Education Summary Matrix .52Appendix E: Recess Summary Matrix .62Appendix F: Classroom Physical Activity Summary Matrix .67Appendix G: Extracurricular Physical Activity Summary Matrix .73The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYWhen children and adolescents participate in therecommended level of physical activity—at least 60minutes daily—multiple health benefits accrue. Mostyouth, however, do not engage in recommendedlevels of physical activity. Schools provide a uniquevenue for youth to meet the activity recommendations,as they serve nearly 56 million youth. At the sametime, schools face increasing challenges in allocatingtime for physical education and physical activityduring the school day.There is a growing body of research focused onthe association between school-based physicalactivity, including physical education, and academicperformance among school-aged youth. To betterunderstand these connections, this review includesstudies from a range of physical activity contexts,including school-based physical education, recess,classroom-based physical activity (outside of physicaleducation and recess), and extracurricular physicalactivity. The purpose of this report is to synthesize thescientific literature that has examined the associationbetween school-based physical activity, includingphysical education, and academic performance,including indicators of cognitive skills and attitudes,academic behaviors, and academic achievement.MethodsFor this review, relevant research articles and reportswere identified through a search of nine electronicdatabases, using both physical activity and academicrelated search terms. The search yielded a total of406 articles that were examined to determine theirmatch with the inclusion criteria. Forty-three articles(reporting a total of 50 unique studies) met theinclusion criteria and were read, abstracted, andcoded for this synthesis.Coded data from the articles were used to categorizeand organize studies first by their physical activitycontext (i.e., physical education, recess, classroom-basedphysical activity, and extracurricular physical activities),and then by type of academic performance outcome.Academic performance outcomes were grouped intothree categories: 1) academic achievement (e.g.,grades, test scores); 2) academic behavior (e.g., ontask behavior, attendance); and 3) cognitive skills andattitudes (e.g., attention/concentration, memory, mood).Findings of the 43 articles that explored the relationshipbetween indicators of physical activity and academicperformance were then summarized.ResultsAcross all 50 studies (reported in 43 articles), there werea total of 251 associations between physical activityand academic performance, representing measuresof academic achievement, academic behavior, andcognitive skills and attitudes. Measures of cognitiveskills and attitudes were used most frequently (112 ofthe 251 associations tested). Of all the associationsexamined, slightly more than half (50.5%) were positive,48% were not significant, and only 1.5% were negative.Examination of the findings by each physical activitycontext provided insights regarding specific relationships.1) School-Based Physical Education StudiesSchool-based physical education as a contextcategory encompassed 14 studies (reported in 14articles) that examined physical education coursesor physical activity conducted in physical educationclass. Typically, these studies examined the impactof increasing the amount of time students spent inphysical education class or manipulating the activitiesduring physical education class. Overall, increasedtime in physical education appears to have a positiverelationship or no relationship with academicachievement. Increased time in physical educationdoes not appear to have a negative relationshipwith academic achievement. Eleven of the 14 studiesfound one or more positive associations betweenschool-based physical education and indicators ofacademic performance; the remaining three studiesfound no significant associations.2) Recess StudiesEight recess studies (reported in six articles) exploredthe relationship between academic performance andrecess during the school day in elementary schools.Six studies tested an intervention to examine howrecess impacts indicators of academic performance;The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance 5

the other two studies explored the relationshipsbetween recess and school adjustment or classroombehavior. Time spent in recess appears to have apositive relationship with, or no relationship with,children’s attention, concentration, and/or on-taskclassroom behavior. All eight studies found oneor more positive associations between recess andindicators of cognitive skills, attitudes, and academicbehavior; none of the studies found negativeassociations.3) Classroom Physical Activity StudiesNine studies (reported in nine articles) exploredphysical activity that occurred in classrooms apartfrom physical education classes and recess. Ingeneral, these studies explored short physicalactivity breaks (5–20 minutes) or ways to introducephysical activity into learning activities that wereeither designed to promote learning through physicalactivity or provide students with a pure physicalactivity break. These studies examined how theintroduction of brief physical activities in a classroomsetting affected cognitive skills (aptitude, attention,memory) and attitudes (mood); academic behaviors(on-task behavior, concentration); and academicachievement (standardized test scores, readingliteracy scores, or math fluency scores). Eight of thenine studies found positive associations betweenclassroom-based physical activity and indicators ofcognitive skills and attitudes, academic behavior, andacademic achievement; none of the studies foundnegative associations.4) Extracurricular Physical Activity StudiesNineteen studies (reported in 14 articles) focusedspecifically on the relationship between academicperformance and activities organized through schoolthat occur outside of the regular school day. Theseactivities included participation in school sports(interscholastic sports and other team or individualsports) as well as other after-school physical activityprograms. All 19 studies examining the relationshipsbetween participation in extracurricular physicalactivities and academic performance found one ormore positive associations.Strengths and LimitationsThis review has a number of strengths. It involved asystematic process for locating, reviewing, and codingthe studies. Studies were obtained using an extensivearray of search terms and international databasesand were reviewed by multiple trained coders. Thestudies cover a broad array of contexts in which youthparticipate in school-based physical activities and spana period of 23 years. Furthermore, a majority (64%) ofstudies included in the review were intervention studies,and a majority (76%) were longitudinal.The breadth of the review, however, is a limitation. Allstudies meeting the established review criteria wereincluded and treated equally, regardless of the studycharacteristics (e.g., design, sample size). The studieswere not ranked, weighted, or grouped according totheir strengths and limitations. The breadth of the review,while revealing a variety of study designs, measures, andpopulations, often made comparisons and summariesdifficult. As a result, conclusions are intentionally broad.Implications for PolicyThere are a number of policy implications stemming fromthis review: There is substantial evidence that physical activity canhelp improve academic achievement, including gradesand standardized test scores. The articles in this review suggest that physical activitycan have an impact on cognitive skills and attitudesand academic behavior, all of which are importantcomponents of improved academic performance.These include enhanced concentration and attentionas well as improved classroom behavior. Increasing or maintaining time dedicated to physicaleducation may help, and does not appear to adverselyimpact, academic performance.6 The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance

Implications for SchoolsThe results of this review support several strategies thatschools can use to help students meet national physicalactivity recommendations without detracting fromacademic performance: School-based physical education: To maximizethe potential benefits of student participation inphysical education class, schools and physicaleducation teachers can consider increasing theamount of time students spend in physical education oradding components to increase the quality of physicaleducation class. Articles in the review examinedincreased physical education time (achieved byincreasing the number of days physical education wasprovided each week or lengthening class time)and/or improved quality of physical education(achieved through strategies such as using trainedinstructors and increasing the amount of active timeduring physical education class). Extracurricular physical activities: The evidencesuggests that superintendents, principals, and athleticdirectors can develop or continue school-basedsports programs without concern that these activitieshave a detrimental impact on students’ academicperformance. School administrators and teachersalso can encourage after-school organizations, clubs,student groups, and parent groups to incorporatephysical activities into their programs and events. Recess: School boards, superintendents, principals,and teachers can feel confident that providing recessto students on a regular basis may benefit academicbehaviors, while also facilitating social developmentand contributing to overall physical activity and itsassociated health benefits. There was no evidence thattime spent in recess had a negative association withcognitive skills, attitudes, or academic behavior. Classroom-based physical activity: Classroomteachers can incorporate movement activities andphysical activity breaks into the classroom setting thatmay improve student performance and the classroomenvironment. Most interventions reviewed here usedshort breaks (5–20 minutes) that required little or noteacher preparation, special equipment, or resources.The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance 7

INTRODUCTIONWhen children and adolescents participate in at least60 minutes of physical activity every day, multiplehealth benefits accrue.1,2 Regular physical activity buildshealthy bones and muscles, improves muscular strengthand endurance, reduces the risk for developing chronicdisease risk factors, improves self-esteem, and reducesstress and anxiety.1 Beyond these known health effects,physical activity may also have beneficial influences onacademic performance.Children and adolescents engage in different typesof physical activity, depending on age and accessto programs and equipment in their schools andcommunities. Elementary school-aged children typicallyengage in free play, running and chasing games,jumping rope, and age-appropriate sports—activitiesthat are aligned with the development of fundamentalmotor skills. The development of complex motor skillsenables adolescents to engage in active recreation (e.g.,canoeing, skiing, rollerblading), resistance exerciseswith weights or weight machines, individual sports (e.g.,running, bicycling), and team sports (e.g., basketball,baseball).1,3 Most youth, however, do not engage in therecommended level of physical activity. For example,Defining Academic PerformanceIn this review, academic performance is usedbroadly to describe different factors that mayinfluence student success in school. Thesefactors fall into three primary areas: Cognitive Skills and Attitudes(e.g., attention/concentration, memory,verbal ability). Academic Behaviors (e.g., conduct,attendance, time on task, homeworkcompletion). Academic Achievement (e.g.,standardized test scores, grades).only 17.1% of U.S. high school students meet currentrecommendations for physical activity (CDC, unpublisheddata, 2009).Schools, which serve nearly 56 million youth in theUnited States, provide a unique venue for youth to meetthe physical activity recommendations.4 At the sametime, schools face increasing challenges in allocatingtime for physical education and physical activity duringthe school day. Many schools are attempting to increaseinstructional time for mathematics, English, and sciencein an effort to improve standards-based test scores.5As a result, physical education classes, recess, andother physical activity breaks often are decreased oreliminated during the school day. This is evidenced bydata from both students and schools. For example, in2007 only 53.6% of U.S. high school students reportedthat they attended physical education class on 1 or moredays in an average week at school, and fewer (30%)reported participating in physical education classesdaily.6 Similarly, in 2006 only 4% of elementary schools,8% of middle schools, and 2% of high schools in theUnited States provided daily physical education or itsequivalent for all students in all grades.7 Furthermore,in 2006 only 57% of all school districts required thatelementary schools provide students with regularlyscheduled recess. As for physical activity outside ofphysical education and recess, during the school day,16% of school districts required elementary schools, 10%required middle schools, and 4% required high schoolsto provide regular physical activity breaks.7In addition to school-day opportunities, youth also haveopportunities to participate in physical activity throughextracurricular physical activities (e.g., school sports,recreation, other teams), which may be available throughschools, communities, and/or after-school programs.8Seventy-six percent of 6- to 12-year-olds reportedparticipating in some sports in 1997,9 and in 2007, 56%of high school students reported playing on one or moresports teams organized by their school or community inthe previous 12 months.6There is a growing body of research focused onthe association between school-based physicalactivity, including physical education, and academic8 The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance

performance among school-aged youth.3,10-16 Thisdeveloping literature suggests that physical activity mayhave an impact on academic performance through avariety of direct and indirect physiological, cognitive,emotional, and learning mechanisms.12,17,18 Research onbrain development indicates that cognitive developmentoccurs in tandem with motor ability.19Several review articles also have examined theconnections between physical activity and academicbehavior and achievement. Sibley and Etnier12conducted a meta-analysis of published studies relatingphysical activity and cognition in youth. Two additionalreviews described the evidence for relationships betweenphysical activity, brain physiology, cognition, emotion,and academic achievement among children, drawingfrom studies of humans and other animals across thelifespan.14,20 Finally, two other reviews summarized selectpeer-reviewed research on the relationship betweenphysical activity and academic performance, with anemphasis on school settings and policies.15,16Research also has explored the relationships amongphysical education and physical activity, fitness levelsand motor skill development, and academic performance.For example, several studies have shown a positiverelationship between increased physical fitness levels andacademic achievement10,21-27 as well as fitness levels andmeasures of cognitive skills and attitudes.28 In addition,other studies have shown that improved motor skill levelsare positively related to improvements in academicachievement29-31 and measures of cognitive skills andattitudes.32-34To extend the understanding of these connections, thisreview offers a broad examination of the literature ona range of physical activity contexts, including physicaleducation classes, recess, classroom-based physicalactivity breaks outside of physical education class andrecess, and extracurricular physical activity, therebyproviding a tool to inform program and policy effortsfor education and health professionals. The purposeof this report is to synthesize the scientific literaturethat has examined the association between schoolbased physical activity, including physical education,and academic performance, including indicators ofcognitive skills and attitudes, academic behaviors, andacademic achievement.How Physical Activity Affects theBrain16-18Cognitive skills and motor skills appearto develop through a dynamic interaction.Research has shown that physical movementcan affect the brain’s physiology byincreasing Cerebral capillary growth. Blood flow. Oxygenation. Production of neurotrophins. Growth of nerve cells in thehippocampus (center of learning andmemory). Neurotransmitter levels. Development of nerve connections. Density of neural network. Brain tissue volume.These physiological changes may beassociated with Improved attention. Improved information processing,storage, and retrieval. Enhanced coping. Enhanced positive affect. Reduced sensations of cravings andpain.The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance 9

METHODSConceptual DefinitionsThe research on this topic suggests that physical activitycan be related to many different aspects of academicperformance (e.g., attention, on-task behavior, gradepoint average [GPA]), and as a result, the existingliterature examines a wide range of variables. Inthis report, those variables are organized into threecategories: 1) cognitive skills and attitudes, 2) academicbehaviors, and 3) academic achievement. The threecategories, as well as other important terms used in thisreport, are defined below.Academic Performance: In this review, academicperformance is used broadly to describe different factorsthat may influence student success in school. Thesefactors are grouped into three primary areas:1) Cognitive Skills and AttitudesCognitive skills and attitudes include both basiccognitive abilities, such as executive functioning,attention, memory, verbal comprehension, andinformation processing, as well as attitudes andbeliefs that influence academic performance, suchas motivation, self-concept, satisfaction, and schoolconnectedness. Studies used a range of measures todefine and describe these constructs.2) Academic BehaviorsAcademic behaviors include a range of behaviorsthat may have an impact on students’ academicperformance. Common indicators include on-taskbehavior, organization, planning, attendance,scheduling, and impulse control. Studies used arange of measures to define and describe theseconstructs.3) Academic AchievementAcademic achievement includes standardized testscores in subject areas such as reading, math, andlanguage arts; GPAs; classroom test scores; andother formal assessments.Physical Education: Physical education, as definedby the National Association for Sport and PhysicalEducation (NASPE), is a curricular area offered in K–12schools that provides students with instruction on physicalactivity, health-related fitness, physical competence, andcognitive understanding about physical activity, therebyenabling students to adopt healthy and physicallyactive lifestyles.35 A high-quality physical educationprogram enables students to develop motor skills,understand movement concepts, participate in regularphysical activity, maintain healthy fitness levels, developresponsible personal and social behavior, and valuephysical activity.35Recess: Recess is a time during the school daythat provides children with the opportunity for active,unstructured or structured, free play.Physical Activity: Physical activity is defined as anybodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletalmuscle that increases energy expenditure above a restinglevel.1 Physical activity can be repetitive, structured, andplanned movement (e.g., a fitness class or recreationalactivity such as hiking); leisurely (e.g., gardening); sportsfocused (e.g., basketball, volleyball); work-related (e.g.,lifting and moving boxes); or transportation-related (e.g.,walking to school). The studies in this review includeda range of ways to capture the frequency, intensity,duration, and type of students’ physical activity.Physiology: In this report, physiology includesindicators of structural or functional changes in the brainand body. Studies most often reported measures ofphysical fitness, motor skills, and body composition fromthis construct.Inclusion CriteriaThe following criteria were used to identify publishedstudies for inclusion in this review. Studies had to Be published in English. Present original data.10 The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance

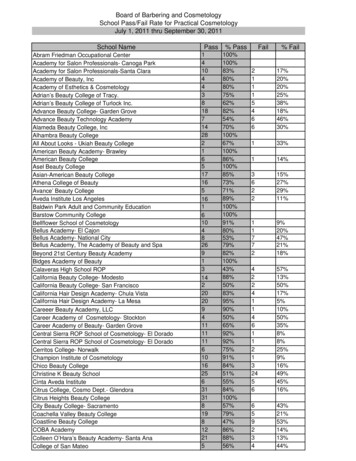

Be published between 1985 and October 2008.* Focus on school-aged children aged 5–18 years. Include clear measures of physical education and/orphysical activity, such as– Physical education class.– Recess.– Classroom-based physical activity (outside ofphysical education and recess).– Extracurricular physical activities (including schoolsports and other teams). Measure academic performance (cognitive skillsand attitudes, academic behaviors, and academicachievement) using one or more educational orbehavioral outcomes. Examples include– Graduation or dropout rates (n 2).– Performance on standardized tests (n 17).– Academic grades/GPA (n 9).– Years of school completed (n 1).– Time on task (n 3).– Concentration or attentiveness in educationalsettings (n 7).– Attendance (n 3).– Disciplinary problems (n 6).– School connectedness† (n 2).Studies were excluded if they did not meet the abovecriteria or if they focused solely on sedentary lifestylevariables, overweight status, or media use ratherthan physical activity. Studies also were excluded ifthey focused exclusively on the relationship betweenacademic performance and fitness test scores rather thanphysical activity itself. Review articles, meta-analyses, andunpublished studies were excluded from the coding andanalysis portion of this review, although their referencelists were used to identify original research to bereviewed for inclusion.Identification of Studies that Metthe Inclusion CriteriaStudies were identified through a search of nineelectronic databases (ERIC, Expanded AcademicIndex ASAP, Google Scholar, PsycNET , PubMed,ScienceDirect , Sociological Abstracts, SportDiscus ),and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied HealthLiterature (CINAHL ) using a pre-established set of searchterms that included both physical activity and academicrelated terms (see Appendix A). Additional studies alsowere located from reference lists of the identified articles.Classification of StudiesThe search yielded 406 articles (see Figure 1). Twotrained researchers examined each article to determineits match with the inclusion criteria; it was then classifiedas “included for review” or “excluded from review.”When the match was unclear, articles were temporarilyclassified as “possible inclusion” before being reviewedby two additional researchers for final classification.Initially, 50 articles were identified for inclusion. Four ofthose articles were later excluded because they lackedclarity necessary to categorize them appropriately for thereview. For example, one article examining movementlacked sufficient information to determine whether themovement should be classified as physical activity;another article lacked a clear academic performancevariable. The other two articles lacked clarity indescriptions of analyses and testing of research questionsthat was necessary for categorization. A fifth article wasexcluded because of its focus on elite athletes rather thana general student population. Two additional articles thatexamined associations between participation in a sportsbased interdisciplinary curriculum and academic gradeswere excluded because of insufficient detail about thephysical activity participation levels of students and thesubsequent lack of fit into the review categories.* Articles published between October 2008 and the publication datethat met the inclusion criteria and made a notable contribution tothe field may have been included in the review based on expertrecommendations.†School connectedness refers to students’ belief that adults andpeers in the school care about their learning as well as aboutA total of 363 articles were excluded. Reasons forexclusion were failure to include an appropriate measureof physical activity (n 103), academic achievement(n 40), or both physical activity and academicachievement (n 25); classification as a review or metaanalysis (n 82); inclusion of participants outside thethem as individuals.36The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance 11

Article Classification SystemFIGURE 1:406Total ArticlesClassified as108Included for Review260Excluded from Review85 of these articles werelater classified as excluded87Excluded from Review21Included for Review38Possible InclusionThese 38 articles were reviewedby 5 team members andthen classified as22Included for Review16Excluded from Review43Total Articles Included for Reviewage range of interest (n 58); inability to obtain full textof the study (n 49); and a publication date outside theinclusion range (n 6).Overall, 43 articles (describing 50 unique studies) metthe inclusion criteria and were read, abstracted, andcoded for this synthesis. Two articles in this reviewpresented findings from more than one study that metinclusion criteria; one article described three studies,37and the other reported six.2Study Coding ProcessWhenever possible, information was abstracteddirectly from articles as stated by authors. The followinginformation was abstracted: purpose, research questions,study design, sampling, sample characteristics, setting,theory, intervention, methods, analytic strategy, results,limitations, study focus, and additional comments. Forthis review, study designs were classified as experimental,quasi-experimental, descriptive, or case studies (studydesigns are defined in Appendix C); data collectionmethods and time points were noted as described.Studies that lacked details regarding any field of interestwere coded as “information not provided.”To ensure consistency in coding, approximately 17%The coding method for this report is similar to that ofof all articles were double-coded by a reviewer and aseveral prominent literature reviews in the public healthsenior coder. A team of article reviewers met regularlyfield.38-40 A team of eight trained reviewers read andduring the coding process to discuss and resolve issuescoded the 43 articles using a standard coding protocolassociated with coding. A system was established for(see Appendix B). When multiple studies were presented handling coding questions and concerns. Senior teamin a single article, this information was noted in themembers resolved and verified issues as they arose.coding, but the studies remained grouped by article. Thecoding protocol involved abstracting information from the A brief summary profile of each study was thenstudies and entering it into a Microsoft Access database. created (see Appendices D–G). A list of the studies12 The Association Between School-Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance

classified as using quasi-experimental or experimentaldesigns is provided at the beginning of each of theseappendices. These summaries were e-mailed to thestudies’ corresponding authors for review and verification.Authors not responding within the initial timeline receiveda second request for review. Seventy-two percent of theauthors (31 of 43) reviewed their summaries. Au

help improve academic achievement, including grades and standardized test scores. The articles in this review suggest that physical activity can have an impact on cognitive skills and attitudes and academic behavior, all of which are important components of improved academic performance. These include enhanced concentration and attention