Transcription

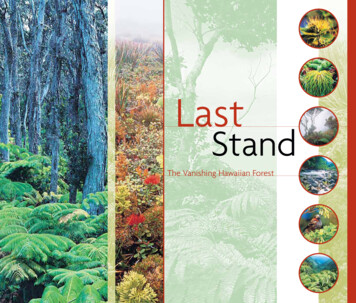

LastStandThe Vanishing Hawaiian Forest

LastStandThe VanishingHawaiian ForestForests can change dramatically over relatively short periods of history. Hawaii's nativeforests evolved over millions of years to become one of the most remarkable naturalassemblages on Earth. Yet since the onset of human arrival, 1,000 years ago, their historyhas largely been one of loss and destruction.The worst damage occurred during the 19th century, when cattle and other introducedlivestock were allowed to multiply and range unchecked throughout the Islands, laying wasteto hundreds of thousands of acres of native forest.The situation became so dire that the captains of government and industry realized thatif the destruction continued there would be no water for growing sugarcane, the Islands’ emergingeconomic mainstay. In response, the 1903 Territorial Legislature created Hawaii’s forest reservesystem, ushering in a new era of massive public-private investment in forest restoration.Today, we reap the benefits of this investment but, ironically, no longer have a wellfunded forest management program. Public investment in watershed protection has droppedprecipitously, and once again the Hawaiian forest stands at a critical historical juncture.The State of Hawai‘i, which has stewardship responsibilities for half of the Islands’1.5 million acres of forested lands, is currently spending less than 1% of its budget to protectall of its natural and cultural resources.The knowledge and tools to protect our forests exist, but almost two decades ofchronic budget shortfalls has left forest managers struggling to sustain watersheds, battlethe nation’s worst extinction crisis, and stem a silent and growing invasion of alien plantsand animals.Hawaii's native forests are among the Earth’s biological treasures, sheltering morethan 10,000 unique species. These forests supply our state with fresh water, protect ourworld-class beaches from destructive run-off and sediment, and are a vital link to the survivalof Hawaiian cultural practices.In the battle to defend these ancient forests, new public-private partnerships haveformed across the state. These partnerships, which reflect a deeper understanding ofthe connection of native forests to water resources, offer perhaps the best hope forlong-term forest preservation. Indeed, only by committing to a new era of public-privatecooperation can we ensure the survival of the Hawaiian forest for generations to come.

The Hawaiian Rain ForestWATER AND THE FORESTWhere DoesHahai no- ka ua i ka ulu la-‘auRains always follows the forestWaterThe Ultimate WatershedA giant living spongeMillions of years of evolution have made the Hawaiian foresthighly efficient at capturing and retaining water. Generallyspeaking, the more complex the structure of a forest, the moreenhanced its watershed functions.The Hawaiian rain forest, withits marvelous multi-layered structure– tall canopy, secondarytrees, shrubs and fern layers, ground-hugging mosses and leaflitter– acts like a giant sponge, absorbing water andallowing it to drip slowly underground and into streams. Evenwithout rain, the forest can pull moisture from passing clouds.In Hawai‘i, this interception can push water capture above andbeyond total annual rainfall by as much as 30 percent.Come From?– Hawaiian proverbhen you live on islands in the middle of a vast ocean, it’sWhard to put a price on the value of fresh water. Without itthere is no life.The Hawaiian Islands lie in a relatively aridpart of the Pacific, 2,500 miles from the nearest continentallandmass, and the rainfall in the surrounding ocean is only25 to 30 inches a year. Yet freshwater is abundant here.Where does it come from?The answer lies in the convergence of winds uponthe Islands’ richly forested mountains. As warm ocean airmoves inland, it is forced upwards by the mountainousterrain, cooling and condensing on its forested slopes.The upland forest captures water in the form of mist, fog,and rain, absorbing and releasing it into streams andunderground aquifers.Water collection is an essential function of allforests, but the Hawaiian forest seems perfectly designedby nature for the task. Its dense canopy provides an umbrellathat intercepts rain. Its thick layered understory acts as agiant sponge, soaking up water. Its roots grip the mountainand anchor the soil, reducing erosion and enhancingsurface water quality.Water is the most important product of the forest,but its supply has always been so plentiful relative to ourneeds, and so cheap, that our awareness of its value hasdimmed. Fresh water is not an unlimited resource, and itsready availability, quality, and sustainability are linked to thehealth of our forested watersheds. When we destroy our forests or allow our watersheds to degrade, we put our futureprosperity and quality of life at risk.The Watershed:N a t u r e’sCollection BasinA conserver of waterThe Hawaiian rain forest is a great conserver of water. The tall, closed canopy shades out the sun,resulting in less water lost to evaporation and transpiration. The dense vegetation also blocks wind,which would otherwise pull moisture from the land. The many layers of vegetation blunt the erosiveeffects of rain, and once saturated, buffer the release of stored water, reducing immediate flow in wettertimes, maintaining it in dry. Long after rain subsides, the forest delivers fresh water for human use.A watershed is an area of land, such asmountain or a valley, that catches andcollects rain water. Topography influences how water moves toward the oceanvia rivers, streams, or via movementunderground. In Hawai‘i, our forestedmountains are our primary watersheds.These areas, which contain both nativeand non-native forests, recharge ourunderground aquifers and provide adependable source of clean water forour streams.A reef saverWater is the most important product of the forest, but its supply hasalways been so plentiful relative to our needs, and so cheap, that ourawareness of its value has dimmed. Fresh water is not an unlimitedresource, and its ready availability, quality, and sustainability arelinked to the health of our forested watersheds.There is a direct correlation in Hawai‘i between thehealth of our forested watersheds and the healthof our reefs and beaches. Without a healthy forestto anchor the soil and temper the erosive effectsof heavy rain, large amounts of sediment wash offour steep mountains and into the ocean, pollutingstreams, destroying coral reefs, and degradingcoastal fishing resources.Our defense against drought and floodPerhaps the greatest value of the thousands ofnative species in our upland forests is the functionthat they perform together, as part of a complex,natural ecosystem.The balance achieved over themillennia has produced forests that can bestweather the typical cycles of drought and floodin the region, and are uniquely adapted to theclimate and soils of the mountain. Native forestecosystems provide the best chance for a stablewatershed, and it would be impossible to replacethem at any price if they were destroyed.WhenWatershedsare DestroyedWhen a forest is degraded, rain fallingon bare earth causes erosion.The waterretaining upper layers of the soil arewashed away, leaving behind lesspermeable clays. Water runs off thisimpermeable surface instead of filteringdown to replenish the aquifer.Streams that emanate fromdeforested mountains flood duringrains. When the rains stop, the streamsrun dry. The loss of stabilizing tree andplant roots results in landslides. Debriscarried by streams quickly ends up inocean coastal areas, smothering reefs.When a native forest is erodedand damaged, opportunistic foreignspecies easily invade. While these newplants can help stabilize bare ground,the watershed cover they create istypically simple in structure and notas effective as that of native forest.

“Of all the places in the world, I would like to see thegood flora of Hawai‘i. I would subscribe fifty poundsto any collector who would go there and work.”– Charles Darwin, NaturalistSCIENCE AND THE FORESTA Storehouseof Biological Richesharles Darwin never made it to Hawai‘i, but other naturalists who did documented its astonishing naturalCdiversity.From its sun-baked coasts to its snow-capped summits, Hawai‘i is an evolutionary wonder, and itsnative forests a storehouse of biological riches.Biologists today are still cataloguing what lives in the Islands’ native forests, but already they havedescribed a litany of wonders: happy-face spiders and carnivorous caterpillars; giant, flowering lobelioidsand brilliantly hued song birds – even a remarkable native fish whose powerful pelvic fins allows it to scalethousand-foot waterfalls.Hawai‘i is home to over 10,000 native species, more than 90% of which are found nowhere elsein the world. Science calls this phenomenon “endemism” – naturally occurring in only one place. High ratesof endemism typically signal biological wealth. With more endemic species than any place of similar size onEarth, Hawai‘i is biologically rich, and its native forests globally important.Forests That Defy NamingHawai‘i has almost as many types of nativeforest as there are U.S. states, including thenation’s only tropical rain forests. ‘Ohi‘a lehua,known for its bright red, orange, or yellowbrush-like flowers, and koa, the highly prizednative hardwood species, are the dominantforest types. But the diversity hardly endsthere. The Big Island has its sub-alpinemamane forests, La- na‘i its dry forests of lamaand olopua, Kaua‘i its mist-shrouded swampforests of dwarf ‘o-hi‘a and lapalapa. Many ofour forest types defy naming. Scientists areforced to call them “diverse mesic forests”because the list of constituent trees is so longand the mix so evenly blended that no onespecies can be called dominant. All total, thereare 48 different native Hawaiian forest andwoodland types and more than 175 differentspecies of native trees, the vast majority ofwhich are found nowhere else on Earth.WhyBiodiversityMattersBorn of volcanic soil and shaped byevolution, Hawaii’s native forests arerich storehouses of biological diversity.But what is biodiversity? And why doesit matter?“Biological diversity” refers tothe variety of life forms on Earth, fromgenes to species to ecosystems. It is thisgenetic variation that allows living thingsto survive change by adapting to differentphysical and biological conditions.Biodiversity plays a critical rolein providing foods and medicines and isessential to maintaining the ecologicalprocesses upon which life depends.Plants, animals, and microorganismsare the cogs within natural systems thatregulate climate and atmosphere, purifywater and air, and maintain soil systems.A biologically diverse forestecosystem provides backup support foressential biological functions. Thus, inthe same way that a diversified stockportfolio enables an investor to weathersudden shocks to the financial markets,a diversified ecosystem allows a forestto recover from natural disasters likedrought, fire, and disease.When we lose our native forests,we lose the important ecological services they provide, as well as a big partof the collective natural and culturalheritage of our Islands. The quality ofour environment and our own quality oflife are diminished. So, too, is the qualityof life that we pass on to our children.-‘ohi‘alehuaSignature Treeof the Hawaiian Forest-‘Ohi‘a lehua can be found almosteverywhere in native Hawaiianecosystems and is the signature treeof the Hawaiian forest. Its scientificname, Metrosideros polymorpha,meaning “many forms,” describes itwell. ‘Ohi‘a grows on sun-scorchedlava and in rain-soaked bogs, andfrom just above sea level to the treeline at 9,500 feet. It can appear asa shrub or an emergent 100-foottree. Its leaves can be smooth andglossy, thick and leathery, coveredwith a dense felt of hairs, andeverything in between. Typically, twoor more forms of ‘o- hi‘a lehua willbe growing next to each other, sodifferent in stature, aspect, leaf andflower, that they look to be entirelydifferent species.

SCIENCE AND THE FORESTA NaturalLaboratoryfor theStudy of Evolutionoceanic island archipelagosRlikeemoteHawai‘i are prized as unparallelednatural laboratories for the study ofevolution. While species that colonizesuch island groups evolve in the sameway as continental species, the processoccurs much faster in an island settingand is more readily observable. Manyof the phenomenon that Darwindocumented in the fabled GalapagosIslands, another isolated island group,and which led to his theory of evolution,find even greater expression in Hawaii’snative forests.Hawai‘i surpasses the GalapagosIslands in the number and varietyof species that evolved from acommon ancestor, a phenomenonscientists call “adaptive radiation.”Over time, and in response totheir environment, species evolveto occupy diverse habitats.Thus,a single Hawaiian tarweedradiated into 36 species, a singlespecies of tree snail became agenus of 40, a single finchproliferated into more than 50species of honeycreepers.Hawaiian lobelioids areconsidered one of the mostspectacular examples of islandevolution in flowering plants. Anearly botanist referred to Hawaiianlobelioids as “the peculiar prideof our flora” because of theamazing diversity of form andhabitat taken by an adaptiveradiation of more than 100Hawaiian species, all derived fromone original ancestor. Hawaiianlobelioids are the world’s largestgroup of related plant speciesendemic to an island archipelago.Liittschwager and Middleton with Environmental Defense 2002When one speciesbecomes manyThe marvels of co-evolutionWhen two interacting species, typically an animaland a plant, evolve together in ways that arebeneficial to both, it’s called “co-evolution.” Inthe Hawaiian forest, honeycreepers and lobelioidsco-evolved in a tight relationship of feeding.The long curved bills of certain honeycreepersfit precisely into the tubular flowers of manylobelioids.The fit of beak to flower is often soprecise that the bird can draw nectar whilemaintaining a clear view of the world, alert foravian predators such as hawks and owls.When herbs become trees“Hawai‘i is the greatest place on Earth to be a biologist.”– Peter Vitousek, Stanford University; Member, National Academy of SciencesThe original plants and animals that colonizedHawai‘i found a place that was free of mammals,reptiles, and most other harmful predators andpests. As a result, many species evolved awaytheir defenses – their thorns and odors and saps.Free to focus their energies elsewhere, manyherbs and shrubs became trees, which helpsexplain why Hawai‘i has such diverse forest types.Scientists call these and other similar evolutionary changes “adaptive shifts.”The Hawaiian forest contains many examples, including the nativenettle, or ma- maki, which lost its stinging hairs, and50 species of“mintless”mints.Hawai‘ihas almostall of Earth’svariationin climate,and most ofits variationin soil.Nature’sUniversityThere are few better natural laboratories than Hawai‘ifor the study of evolution, the role of individual speciesin an environment, and the complex relationshipsbetween organisms.Not only is the Hawaiian archipelago wellisolated, but as Darwin noted, its main islandsare well isolated from each other. Each is adifferent geological age and boastsendemic species.Hawai‘i has almost all of Earth’svariation in climate, and most of itsvariation in soil. Rainfall rangesfrom eight inches a year to morethan 400 inches, and temperaturesfrom near desert heat to freezing.In addition, elevation changes aredramatic, rising quickly from sea levelto summits approaching 14,000 feet.All of this spectacular variation is found in avery small area, and it’s almost all on one kind of rock,with ecosystems that are neatly organized – by lavaflow, by elevation, by side of the mountain, by island.All of these factors work to produce extraordinarynative forests that enable scientists to conductresearch in ways that can be duplicated in few otherplaces. Armed with this knowledge, scientists canmeasure biodiversity, assess its potential threats,and design methods to protect it.

HAWAIIAN CULTURE AND THE FORESTWood – Mainstay ofthe Material CultureThe RootsA u w -e !of our Culturecultural traditions reflect aHlong,awaiianclose-standing relationship with theWao Akua“Realm of the Gods”FishpondThe Ahupua‘aWao Kanaka“Realm of Man”native forest. In ancient times, the forestwas celebrated in chant, song, and dance,and its many gifts provided for the spiritualand material needs of the culture.Water from the forest fed the lo‘i(taro fields) in the lowlands and thefishponds along the coast. Woods fromforest were used to make houses, canoes,weapons, and tools. Forest plants andherbs were gathered for healing andmedicinal purposes, and the feathers ofbirds fashioned into brilliantly coloredcapes, helmets, and lei.A deep reverence for the naturalworld permeated ancient life. Hawaiianssaw themselves as part of, not separatefrom, nature.The land was the ‘a-ina, or“that which feeds,” and its rich diversityhelped shape and inspire the nativeculture.Today, the survival of an authenticHawaiian culture is inherently tied to thepreservation of the forest and the naturalenvironment in which its traditionsevolved.“To maintain our ownbeauty, we must maintain thebeauty of the forest,” saysKumu Hula Pua Kanahele.“If we cut down the forest,we cut down ourselves.”Ancient Hawaiian lifewas based around theahupua‘a system of landmanagement, whichevolved to protect the uplandwater resources that sustainedhuman life. A typical ahupua‘a, orland division, was wedge-shaped and extended from the summitsinto the sea. As water flowed from the upland forest, down throughthe ahupua‘a, it passed from the wao akua, the realm of the gods, tothe wao kanaka, the realm of man, where it sustained agriculture,aquaculture, and other human uses. Water was a gift from the gods,and all Hawaiians took an active part in its use and conservation.Liittschwager and Middleton with Environmental Defense 2002The HawaiianRelationshipto NatureIn the ForestReside the GodsThe ancient Hawaiians sawgods everywhere in natureand worshiped a pantheonof natural deities.Theupland forest was waoakua, the realm of thegods, and the trees were aphysical manifestation ofthis spiritual realm. Entryinto the forest was limitedto a few consecratedindividuals and involved astrict protocol, including anoffering and a statement ofidentity and purpose. If thepurpose was to collecttrees, only a single tree orspecies could be collectedat a time.The upland forestwas sacred to Ku-, the godof war, governance, andleadership.‘Ohi‘a lehua wasthe physical manifestationof Ku-, and the taking of alarge ‘o- hi‘a was regardedas a sacred act, requiringa human sacrifice.Early Hawaiians possessed an especially detailed knowledge ofthe differing physical characteristics of wood.Trees such as‘o- hi‘a lehua, lama, and naio were often chosen for thebasic framework of a house, while endemic hardwoodssuch as kauila, uhiuhi, olopua, and koa were used tofashion spears, daggers, and clubs. Wiliwili, a woodof the dry forest, was known for its buoyancy and usedfor making fishing floats and surfboards, while koawas used for making canoes, bowls, containers, andtools. Wood played a singularly important role in allaspects of Hawaiian life. Shelter, agriculture, fishing, foodpreparation, storage, transportation, weaponry, and religionall included key structures or tools made from the different treesavailable in the native forest.Ancient Hawaiians believed they weredirect kin of the plants and animalsthat shared their world, and thatboth animate and inanimate thingspossessed spiritual power, or mana.They believed that beings with greatmana could take on the form ofother plants and animals, and thatone’s spirit might cycle through otherliving things after human death. Insuch a world, you could talk directlyto the winds and rains and expect aresponse, or have the ‘io, the Hawaiianhawk, as your ancestral guardian,watching over you from his perch inthe forest.As the youngest descendents among living family, humanshad the role of caretakers, while theplants and animals, as the oldersiblings of the ‘a- ina, providedguidance.The saying goes: He ali‘ino- ka ‘a- ina, he kauwa- wale kekanaka. The land is chief, thehuman is but a servant.In the early 1990s when the double-hulled Hawaiianvoyaging canoe, Hawai‘iloa, journeyed to Tahiti, itwas the first modern canoe of its kind createdas much as possible from native materials.During its conception, however, theHawai‘iloa hit a significant snag: a yearlong search through the native forestsof the Big Island identified only two livingkoa trees large enough for her hulls.For master navigator Nainoa Thompson,the discovery came as a shock, and hefound that he could not, in good conscience,remove the trees from the forest. Instead, hetraveled to the Pacific Northwest where he asked twotribes of native Americans for a gift of two largespruce trees. The experience instilled in Nainoa astrong conviction that preservation of the native forestis fundamental to Hawaiian cultural revival.“Each time we lose another Hawaiian plant or bird orforest, we lose a living part of our ancient culture.”– Nainoa ThompsonPolynesian Voyaging SocietyHula and the ForestIn Hawaiian culture, Laka, the goddess of hula,is a forest deity, and so are the various plants thatare sacred to the dance, including ‘o- hi‘a lehua,maile, and palapalai ferns. When the ancientswent to the forest to gather the materials withwhich they made their lei and costumes, they weremindful of a conservation ethic that is deeplyrooted in old Hawaiian ways: Take from the forestonly what you need. Chant and give thanks.Featherworkin Old Hawai‘ifeathers of many endemic forest birds were usedTtohefashioncapes, cloaks, helmets, and lei of spectacularbeauty in old Hawai‘i. Feather garments were a symbolof high social rank.They were worn only by royalty andconnected the chiefs to the gods.The red feathers ofthe ‘i‘iwi and the ‘apapane, and the yellow feathers ofthe now extinct ‘o-‘o- and mamo, predominated, but black,white, green, and other colors were also used. Whilefeatherwork may have contributed to the decline ofmany native birds, examples of the art form are amongthe most treasured objects to be found in the Pacificcollections of the world’s greatest museums.

THREATS TO THE FORESTDeadly InvadersForestsUnder Siegeyou go in Hawai‘i, theAnativelmostforesteverywhereis under siege. Goats are eatingtheir way up the side of the mountain inEast Moloka‘i. Miconia calvescens, the“green cancer,” has a foothold on Mauiand the Big Island. Feral pigs have spreadinto every watershed in the state.Remote, oceanic islands are morevulnerable to ecological invasions thatany other ecosystems. In Hawai‘i, thedamage done by feral cattle, pigs,goats, rats, weeds, wildfire,invasive insects, and other threatsintroduced by people has renderedthe Islands’ native forests amongthe most endangered in the world.Since the onset of humanarrival, Hawai‘i has lost almosthalf of its native forest cover.While the historical impacts fromagriculture, grazing, logging, anddevelopment are responsible for much ofthis loss, the greater threat today is thedestruction wrought by invasive plantsand animals.Non-native species prey upon anddestroy the habitat of native species, competewith them for food and habitat, and spreadforeign diseases. Over time, they can transform the forests they invade, changingthem from native to non-native, simplifyingtheir structure, altering soil composition,sucking up scarce water, and increasingthe risk of fire.“The Green Cancer”WildfireExcept in active volcanic areas,fire is not a part of the naturallife-cycle of native Hawaiian ecosystems, and only a few speciesregenerate after a fire, if at all.The void they leave is quicklyfilled by fire-adapted alien weeds,which increase the risk of futurefires.This vicious cycle of destruction has played out on Moloka‘i,which has seen four major firesin the last 20 years. Previousfires allowed flammable aliengrasses to gain a foothold, andwith each new fire they spreadfurther. The worst fire covered13,000 acres and destroyed someof the last remnants of lowlanddry forest and rare species.Miconia is recognized as the mostinvasive and dangerous alien plantspecies of Pacific Island rain forests.This fast-spreading LatinAmerican plant casts a dense shadethat kills everything beneath it, andits shallow roots cannot hold the forest floor’s exposed soil. Over time adiverse, multi-layered native forestbecomes a single-species miconiaforest, prone to landslides. Incipientmiconia populations on O‘ahu andKaua‘i have been cleared, but moreaggressive and sustained effortsare needed for Maui and theBig Island, where this weed infeststhousands of acres.Rototillers of the ForestWild pigs are widespread inHawaii’s native forests. Wherethey root and trample, theydestroy native vegetation,accelerate erosion, spreadweeds in their droppings, andpollute the water supply witheroded silt, feces, and foreigndiseases. Pigs eat the nestlingsof ground nesting birds, andtheir wallows create breedingsites for foreign mosquitoes,which spread deadly diseasesto Hawaii’s endangeredforest birds.Avian PerilThe Hawaiian archipelago oncesustained at least 140 speciesof native birds. Seventy of thosespecies are now extinct, andanother 30 are endangered. ForHawaii’s remaining forest birds,introduced mosquitoes thatspread avian malaria and otherdiseases are a primary threat.Koa KillerBanana poka, a non-native vineintroduced to Hawai‘i from SouthAmerica, has smothered over70,000 acres of prime nativeforest. Hardest hit have been thestate’s precious koa forests, whichsupply Hawaii’s most renownedhardwood and support many rarebirds and plants.“Far wiser to nip these pests in the bud before theybloom into expensive and formidable plagues.”Dangerous BeautyUsing their antlers to girdle andkill native trees, axis deer wreakhavoc on native Hawaiian ecosystems. Like other hoofed animals, they trample and eat nativevegetation, spread non-nativeweeds, and greatly contribute toerosion. Axis deer have alreadyproven their ability to destroyHawaiian forests on La-na‘i andMoloka‘i.They now threaten todo the same on Maui.Rats!Cannibal SnailRats are widespread in Hawai‘iand their impact on native forestsis profound. Rats dine on nativesnails and raid the nests ofnative birds.They devour theseeds and fruits of native plants,as well as many of the nativeinsects these birds and plantsrely upon. In the end, they canshut down natural regenerationof our native species andcontribute to their decline andextinction.– Honolulu Star-BulletinIn addition to rats, one of the greatestthreats to Hawaii’s endangered treesnails is the carnivorous rosywolfsnail. Native to Florida andCentral America, the wolfsnail wasintroduced to Hawai‘i in 1955 in amisguided attempt to control anagricultural pest, the giant Africansnail. Wolfsnails eat all snailsregardless of size and have decimatednative Hawaiian snail populations.Wolfsnails even devour their ownspecies, giving them the commonname “cannibal snail.”An Ounce of Preventionfederal, and private managers of Hawaii’s forestsSspendtate,morethan 75% of their resources to prevent thespread of alien pests, and repair the damages theycause. The best way to protect our native forests fromfurther invasions is through enhanced prevention –stopping alien pests before they get here, or beforethey spread. For example, experts warn that Hawaiicould soon have established snake populations if severalpractical steps are not taken now. Hundreds of crediblesnake sightings have been reported in the Islands, andmost of those snakes were free-roaming and notrecovered.“Once you allow an invasive pest to becomeestablished, it’s almost impossible to eradicate, saysMaui scientist Lloyd Loope of the U.S. Geological Survey.“Expensive control costs are permanent. There’s noputting the mongoose back in the cage.”TheExtinctionCrisisHawai‘i has the dubious distinctionof being home to more than onethird of the birds and plants on theU.S. Endangered Species List. Whenspiders, snails, and insects areincluded, nearly 60% of Hawaii’s totalnative flora and fauna is imperiled,by far the highest percentage ofany state. Destruction and the lossof forest habitat is the primarycause of species decline. If we areto preserve our remaining nativeforests and prevent further speciesloss, we must halt the continuinginvasion of non-native plants andanimals that is undermining theecological stability of our Islands.

Liittschwager and Middleton with Environmental Defense 2002Biodiversity and Scientific StudyHawaii’s native forests are one of the world’sbiological treasures and a natural laboratory for the study ofevolution. Studies of Hawaii’s native plants and animals have alreadyrevolutionized scientific understanding of how species evolve.AestheticsThe scenic beauty of Hawaii’s rain-forestedmountains is of great value to Island residentsand a primary visitor attraction.Ground water qualityWhat are 4.5 - 8.5 billionOur Forests Worth?are more renowned for their natural environment than Hawai‘i.FYetewasplacesa state we devote little money to its protection and essentially take for* “Environmental Evaluation and the Hawaiian Economy,”prepared by the University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization.Principal investigator: Jim Roumasset. 83.7 - 394 millionIn-stream uses 82.4 - 242 millionSpecies habitatBiotechnologyResearch into the genetics of the Islands’ native biodiversitycould have a significant impact on medical science, geneticengineering, and agricultural biotechnology. 487 million - 1.4 billionBiodiversity 660,000 - 5.5 millionTotal Value ofGoods and Servicesfrom a Single HawaiianLiittschwager and Middleton with Environmental Defense 2002granted the many benefits it provides.In the case of our forests, w

and the mix so evenly blended that no one species can be called dominant. All total, there are 48 different native Hawaiian forest and woodland types and more than 175 different species of native trees, the vast majority of which are found nowhere else on Earth. Signature Tree of the Hawaiian Forest 'O-hi'a lehua can be found almost