Transcription

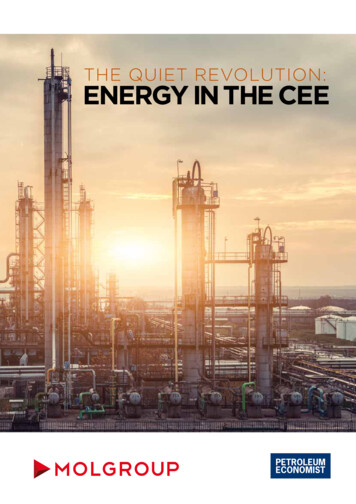

THE QUIET REVOLUTION:ENERGY IN THE CEE

ACCEPTOR CHALLENGE?At MOL Group we address the challenges of innovation, regulation and changingcustomer demand. We are leading the industrial transformation in Central andEastern Europe by becoming the premier chemicals company, by diversifying ournon-fuel products, and by being the first choice of those on the move.SEE THE INDUSTRY OUR WAYmolgroup.infoFollow us on

NEW DYNAMICSThe energy economics of Central andEastern Europe are changing. Onegroup, MOL, has recognised that thereare opportunities among the difficulties,says Zsolt Hernadi, chairman and CEOCONTENTS04 The quiet revolutionPolitical and economic sands are shiftingin the CEE – for the better08 Mapping growthCEE oil and gas infrastructure, laid out byPetroleum Economist’s cartography team10 Economics of growthThe CEE is set for growth, but wouldbenefit from wider geopolitical stability12 Opportunity in diversityRegional finances are set for steadygrowth, and wider stability beckons14 CEE oil and gas companiesembrace Energy UnionBy working together, regional players canfeel the benefits of scale economicsEditorDerek BrowerManaging editorMichael McCawDesignSam MillardCartographyKevin Fuller, Peregrine BushPublisherElliot ThomasThe Petroleum Economist Ltd is part of Gulf PublishingHoldings LLC. Registered in England. Company No:04531428 All rights reserved. Petroleum Economist is aRegistered Trade Mark. Petroleum Economist, London,2016. Reproduction of the contents of this publicationin any manner whatsoever is prohibited without priorconsent from the publisher.Over the past 15 years, MOL has moved to apre-eminent position in Central and EasternEurope (CEE), becoming a truly internationaloil and gas company with market-leadingpositions across the core parts of our business.We committed ourselves to internationalgrowth and the efficient operation of ourintegrated business model, setting the pacein regional consolidation. In that period, ourearnings have grown seven-fold and marketcapitalisation has grown five-fold.Since well before the current downturnin global oil prices, MOL has endeavoured– successfully – to improve the efficiency ofits downstream operations and grow its retailnetwork, whilst optimising and intensifyingupstream performance in the region. Theoil price context since mid-2014 has merelyproved that this was the correct path to take.MOL faces the same challenge as itspeers, however – how to evolve andcontinue growing in a lower carbon future,characterised by constant technologicalinnovation and ever-shifting customer habitsand needs. At MOL we see this time of changeas a clear opportunity to improve ourselves,rather than a threat to be resisted. Using thecapability, the financial means and the leadingregional market position we have built up asa foundation, we want both to address thisopportunity and to ensure that our businesscan respond dynamically to future trends.It’s true that with our resilient businessmodel we are well-positioned to continue todeliver strong returns, but by no means will webury our heads in the sand. Now is the timeto lay down the foundations of operations thatare sustainable in the long term.MOL recently set out its new longterm strategy, “MOL Group 2030 – EnterTomorrow”, the objective of which is not onlyto sustain and strengthen our regional positionin our core businesses, but also to once againdrive the changes in CEE.Demand for hydrocarbon-based motor fuelslooks certain to decline in the long run. As MOLlooks to diversify from motor fuels, we willfurther diversify and expand our petrochemicalsportfolio with the aim of becoming a leadingchemical company in CEE.While the on-going drive for greaterefficiency and profitability at MOL’s refinerieswill continue, we are also looking to grow theshare of non-motor fuel products, movingup the value chain to target those semicommodity and speciality petrochemicalproducts with a higher added value.We believe that serving one millioncustomers every day across our CEE retailnetwork gives us insight into the needs ofconsumers – and these needs are changing.MOL is aiming for an evolution in retailsimilar to that in its petrochemicals business,so that customers use our network of servicestations to do more than just fill up their cars.Upstream will continue to play a key role,operating profitably and adding value even ina low oil price environment. This will meanmaximising value from MOL’s existing assetbase, while sustaining our production at leastat today’s level.I am confident that through thecombination of our high quality assets,financial strength, growing markets, talentedpeople and the right corporate culture, MOLwill once again set the pace for the next 15years, offering competitive returns to ourshareholders and contributing to the longterm social and economic prosperity of theeconomies in the region.THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEE 03

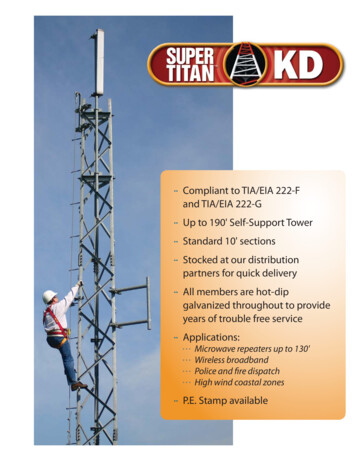

THE QUIETREVOLUTIONAs the energy infrastructure in the CEE developsacross a number of projects, the political andeconomic sands are shifting – for the betterAs the north-south gas corridor steadilyapproaches completion, it brings closer theEU’s strategy of making Central EasternEurope more energy independent. Of vitalimportance to Brussels in the wake of thegas crises of 2006 and 2009, the corridorwill enhance regional interconnectivity withliquefied natural gas terminals located at eachend of the system.A significant bonus is that regionalinterconnectivity will enable liquid gasmarkets with gas-on-gas competition bygiving access to LNG sources.Much of the infrastructure is already inplace. One of the first countries off the markwas Hungary, where two large gas storageshave been built and interconnectors developedwith most of the neighbouring nations.However there’s still work to be done.Although the Polish LNG facility hasbeen completed at the northern end, thesouthern end needs extra infrastructure toreduce bottlenecks and boost flows. Just oneexample: there’s still no reverse flow capacity04 THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEEon the Hungary-Croatia interconnector intoHungary due to missing developments onthe Croatian side, and the LNG terminalproposed for the Croatian island of Krk is atan early stage of development. It will requirethe support of the Croatian government andthe EU in order to reach completion.The delays have been particularlydisappointing for Hungary which has been anearly champion of an efficient, integrated gasmarket at both domestic and regional levels.On a brighter note, a broad and high-levelinitiative has been formed to speed up gasintegration in the wider region. Under theumbrella of the Central and South EasternEuropean Gas Connectivity (CESEC), itcombines 15 nations with a vital interest inthe creation of a gas network. Establishedin early 2015, CESEC is working to resolveinterconnector delays by taking intoconsideration all relevant issues includingthose pertaining to regulation, technologyand finance.The results are already showing up. InSeptember CESEC signed off four importantinitiatives. The so-called BRUA project, one ofthe most important for the region, connectingBulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Austria isgaining traction. Four countries – Greece,Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary – agreedto work together on the “ vertical corridor”that would share gas between them. Amemorandum of understanding was signedon achieving reverse flows on the trans-Balkanpipeline.And Bulgaria and Romania declaredthemselves close to completing aninterconnector that would also have the knockon effect of facilitating more interconnectionswith neighbouring countries.With all this going on, the CEE is nowfar better-placed in the diversification ofits gas imports than it was a decade ago. Atpresent Russia provides almost a quarter ofEurope’s natural gas but the CEE is much lessdependent on this supplier than it was. Andas Brussels is beginning to deploy funding forthe further development of gas infrastructure,

MUCH HAS BEEN ACHIEVED INTHE LAST FEW YEARS IN OIL ANDGAS SECURITY IN THE REGION,PARTICULARLY SINCE THERUSSIAN INVASION OF EASTERNUKRAINE AND THE EARLIER GASCRISIS OF 2009An LNG tanker cruises toward PolandRussia’s influence on the region’s energy needswill inevitably reduce.Meantime think tanks such as the GermanInstitute for Economic Research believe thatexisting infrastructure could be used moreefficiently, but that would require morecooperation between Member States thanthere is at present. That view coincides withthat of energy companies such as Hungary’sMOL, which believes that small but essentialadd-ons to the existing networks, combinedwith scalable projects, offer the best bang forthe buck.The increase in LNG terminals will beimportant in gas integration in the region. Thebiggest such terminal in northern and centraleastern Europe, Świnoujście in Poland, cannow handle methane carriers with a capacityof between 120,000 cubic metres and, inthe case of the Q-Flex class, 217,000 cm.And much of that gas can now be pipelinedbeyond Poland into other CEE countries. AsJan Chadam, president of terminal operatorPolskie LNG, pointed out at the time of theinaugural berthing: “The receiving terminal’spotential makes us an important player inenergy independence in the whole region.”Before that happens though, Poland needsto install missing infrastructure such as aPoland-Slovakia interconnector that wouldboost the flow of its LNG to the rest of theCEE. Gas experts also say Poland needs todevelop its internal network.The EU has earmarked a considerablebudget to subsidise the financing of the CEE’spipelines.Starting in 2009 with a sum of 4bn, thenow-replaced European Energy Programmefor Recovery (EEPR) saw its capex capabilityexpand rapidly in the wake of the UkrainianRussian conflict, which jolted Brussels outof its complacency over the region’s andEurope’s energy independence. The currentbudget devoted to the expansion of Europe’sgas network between now and 2025 is about 5.35bn.The increase in the number and capacity ofthe pipelines, particularly those devoted to gas,contributes to energy security right across theregion because of the interlocking nature ofthe network. For instance, when the recentlyannounced 187m Baltic interconnectorlinking Finland and Estonia is activated in2020, it will unite the eastern Baltic Sea regionwith the rest of the European energy market.In the event of a crisis such as occurred in 2009when Russia turned off the pipeline throughUkraine, the new pipeline will take some of thepressure off the CEE.Technically challenging, the pipeline willrun 172km including 80km off shore. A twoway transmission system, it will transport7.2m cubic metres of gas a day in bothdirections. But when the gas starts flowing,energy consultants point out that the benefitfor Finland – until now heavily reliant onRussian gas – and the broader Baltic regionwill be historic. Thus the planned pipelinewould have an important symbolic as well aspractical value if built.As smaller but essential developmentstake place, big-ticket projects are exercising aprofound influence on gas supplies and willcontinue to do so.For instance, Nord Stream 2. Germanyappears committed to it in the face ofconcerted opposition.As Russia attempts to decrease its exposureto Ukrainian transit to Central Europe,Germany has striven to take over the role ofEurope’s gas transit hub with the help of theNord Stream pipeline that transports Russiannatural gas to Western Europe underneath theBaltic Sea. This is a position Germany wouldcement if Nord Stream 2 were to go ahead.The CEE is concerned about the project,THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEE 05

Poland’s Šwinoujšcie, one of thelargest LNG terminals in Europemainly because it runs counter to the EUrulebook on energy.Not only would it dramatically alter the gastransit axis and dominant flows, it would causecurrent gas transit income received by Polandand Slovakia to fall dramatically.At the same time, warns the CentralEuropean Policy Institute (CEPI), it wouldundermine the efforts undertaken by CEEcountries such as Hungary, with the backingand financial support of the EU, to diversifytheir gas markets.In its support for Nord Stream 2, Germanyalso puts itself at loggerheads with Brussels.As CEPI explains, the pipeline would improveGermany’s energy security at the expense ofthe economic and energy security of the CEE.More recently, in late July Slovakia’s MarošŠefčovič, Vice President of the EuropeanCommission for energy, openly attacked theentire rationale for Nord Stream 2.As he argued, the original basis forthe pipeline has been undermined bythe approximately 50% fall in the cost ofseaborne LNG deliveries in the last few years06 THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEEas well as by the mushrooming of receivingterminals around the Caspian Sea and theeast of the Mediterranean, with yet more onthe drawing board. “But in particular, gas istransported more and more by sea routesunder liquefied form,” he explained. “Pricesare very competitive.”And although the South Stream pipelineacross the Black Sea was cancelled in 2014and supposedly buried after Russian PresidentVladimir Putin announced his country’swithdrawal from the project in the teeth ofopposition from Brussels, some believe it’sstill on the agenda.In July 2016 Dušan Bajatović, head ofSerbia’s state-owned provider of natural gasSrbijagas, expressed his conviction that theproject will eventually happen – because ithas to.“One way or another, the South Streamwill be completed,” Bajatović predicted on thebasis that by 2035 Europe will require 150bncm more natural gas per year than it currentlyimports.Much has been achieved in the last fewyears in oil and gas security in the region,particularly since the Russian invasion ofeastern Ukraine and the earlier gas crisisof 2009. Generally, points out CEPI, gasinfrastructure has been strengthened andseveral two-way cross-border pipelines havebeen switched on.Poland, for instance, can now be suppliedfrom western hubs and Gaz-System, the Polishoperator, is implementing interconnectionswith Lithuania, Slovakia and the CzechRepublic. Also, despite entertaining biggerambitions, Slovakia now benefits from a twoway flow across its border with the CzechRepublic. It has also boosted the AustrianSlovak interconnector capacity and has a newinterconnection with Hungary and Ukraine.As the CEPI explains: “Compared to a fewyears ago, [the region’s] energy security hasimproved, especially in gas.”Indeed experts have coined the phrase“quiet gas revolution” to describe the progressthe CEE has made, admittedly after beingshocked into action by the events of 2009 and2014.

But there are a lot more projects on thehorizon. According to CEE’s Gas RegionalInvestment Plan (GRIP), a cooperativeinitiative launched by the European Networkof Transmission System Operators for Gas(ENTSOG), there’s a busy programme to becompleted between now and 2025. In all, 88sizeable projects are planned in the region. Ofthese, 24 are already fully funded and 64 areunder development.One such landmark project is the gasinterconnector between Poland and Lithuania,part-funded by 30m from Brussels. Due tobe turned on in 2019, the interconnector willhook up several CEE countries to gas storedin a floating LNG terminal in Klaipėda onLithuania’s Baltic coast. The pipeline will,points out CEPI, “put an end to the [energy]isolation of the Baltic states.”In 2014 the European Commissionconducted a stress test of the vulnerability ofthe CEE’s gas supplies. The verdict, as thosebehind CESEC explained, was “extremelyvulnerable” to the risk of a cut by its biggest,and in some countries, sole supplier. Andcompared with Central Western Europe,consumers were paying a lot more for theirgas. CESEC concluded: “The main reasonswere missing cross-border infrastructure andpoor implementation of energy market rulesthat would allow reliable gas supplies from adiverse range of suppliers to be delivered ataffordable prices to consumers.”Since then CESEC has overseen a rapidturnaround in gas integration. No longeris the CEE so vulnerable – and, as theorganisation predicts, soon it will be even lessso. As Šefčovič said in September: “In workingtogether we can achieve heightened energysecurity and diversification in a region whichhas already experienced a severe vulnerabilityto its gas supplies.”Impressed by what it’s been able to achieve,CESEC has lately embraced even biggerambitions.Its members have decided to extend theircooperation into renewable energy and energyefficiency by reducing their dependence onexternal suppliers, just as they’ve managed todo with gas. Next up, predicts Commissionerfor Climate Action and Energy Miguel AriasCañete, is the creation of a regional electricitymarket.But companies in the region have notneglected the importance of oil supplydiversification as a key element of the CEE’senergy security. MOL, for instance, haveinvested in the Friendship I/Adria crude oilpipeline in order to be able to potentially fullysupply its Danube and Bratislava refineriesfrom the Adriatic. MOL plans to increase itsIN ALL, 88 SIZEABLE PROJECTSARE PLANNED IN THE REGION. OFTHESE, 24 ARE ALREADY FULLYFUNDED AND 64 ARE UNDERDEVELOPMENTA border delivery station at the natural gas pipelinenear Rozvadov, Czech Republiccrude intake from the Adriatic to 33% in thenext few years to process the most profitablecrude and to match the demand for itsproducts.Other oil companies are following suit inthe pursuit of extra output, important in aregion that is in the middle of what could bea long-term process of diversification in itssource of oil. During 2016, crude from theMiddle East – notably Iran, Saudi Arabia andIraq – has been shipped into the CEE on alarger scale than before.As with gas, the region has historically beensupplied by Russia, mainly pipelined fromthe Urals, and the European Commission isconcerned that the burden of supply does notfall on one country. Poland and Germany,for instance, are particularly dependenton Urals crude. That’s why the berthing ofthe supertanker Atlantas in Gdansk in thesummer with a cargo of Iranian crude wasseen as symbolic.Similarly, the opening of the Naftowy Pernoil terminal – also in Gdansk – in April hasbeen greeted within the EU as another stepforward in the region’s energy diversificationbecause it provides Poland with anothersource of supply.Both these developments follow Poland’sPKN Orlen agreement of a long-term contractlast year with Saudi Aramco – its first ever –for delivery of crude to the Polish outfit’srefineries. PKN Orlen also has long-termcontracts with Rosneft. Some of the Saudioil will be moved to Lithuania and the CzechRepublic.Although, as oil experts point out, thecontinuation of Middle East-sourced crudedepends significantly on favourable shippingrates and the volumes hardly put a dent inRosneft’s supplies, they do mark a milestonein the region’s pursuit of energy security.Meanwhile, the Czech Republic’s Unipetrol– owned by PKN Orlen – is also in the marketfor Adriatic oil. The firm recently signed up toa three-year agreement for the transportationof crude oil to refineries in Kralupy andLitvinov, via the Adria pipeline. The agreementshould provide the Czech Republic withgreater crude supply security, mimicking thecharge towards a more stable energy marketacross the region.THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEE 07

MAPPING GROWTH:CEE OIL AND GAS INFRASTRUCTURE 08 THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEE ¡ ¡

THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THECEE 09

ECONOMICSOF GROWTHRegional finances are set for steady growth,but the CEE could benefit from widergeopolitical stabilityIt’s just as well the oil and gas industry acrossthe CEE is used to economic and politicalupheaval. For most of the last 20 years, it’s hadto deal with almost continuous change and it’sbecome a way of life for commerce in generalin the region.As PWC Poland’s senior economistMateusz Walewski observed earlier this year,“international and local businesses havebecome used to continual reform over thisperiod and executives say it has helped themto become more agile and less fragile.”And these nations have to be agile. “Themajority of CEE countries are small, relativelyopen and heavily dependent on exportsfor growth, notably to other EU countries,”Walewski adds. “This makes them highlysensitive to developments in advancedeconomies.”Economists generally divide the region’scountries into three quite distinct camps. Thereare the smaller Baltic states, the next-biggestand export-focused economies such as theCzech Republic, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungaryand Poland, and the troubled countries suchas heavily indebted Slovenia. The nimbler10 THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEEones such as the Baltics are expected to growat a rapid rate – up to 4% a year betweennow and 2020 – while the export-orientedcountries with “reasonably friendly businessenvironments”, says Walewski, should achievecollective annual growth of between 2-3%.Of the latter, Romania, Slovakia, theCzech Republic, Hungary and Poland areprime examples. They already serve as a vitalelement of the European supply chain inmanufacturing, particularly in the automotiveindustry. Just two in fact, the Czech Republicand Slovakia turn out more cars than doesFrance despite having just 16m peoplebetween them.Ominously, they are increasinglyapplying their engineering know-how to thedevelopment of home-grown brands andcompeting in the wider European market intheir own right. Clearly this will be importantfor the development of the region’s energysector. And it’s why, estimates consultancyFocusEconomics in a recent forecast, Romaniawill be the region’s fastest-growing economyin 2016 with a predicted rate of 4.5%, closelyfollowed by Poland and Slovakia, both witharound 3.2%.Although the CEE is seen as a cohesiveregion, most observers believe economicprospects will vary considerably, accordingto how capable their governments dealwith current challenges including that ofBrexit. “The Brexit decision will likely dragon confidence and might contribute to afurther weakening of investment [in theregion], which has already been decliningdue to lower inflows from EU funds,” predictsFocusEconomics.Energy outlookThe oil and gas industry has had a particularlyturbulent period created by rock-bottomcrude prices exacerbated by Iran’s return to oilexporting after the ending of an internationalban, the after-shocks of the attempted coup inTurkey that has already affected exports fromseveral countries such as Romania, and theslowdown of Brussels-based investment.The good news in all of this is low-costfeedstock.With its ability to transcend national issues,the region’s oil and gas industry is profiting

Rising Danube: regional economics are looking strongfrom the ever-cheaper crude that is fuellingthe downstream industry. “Taking advantageof cheap feedstocks, refiners have made themost of larger profit margins and producinghigher value products,” points out the WorldRefining Association in its latest report on theregion.Rather than rely on the feedstock windfallthough, industry in the CEE has launched itsown initiatives. “There has also been a hugefocus on driving efficiency, cutting costs andadapting to change,” adds the association.Only by creating efficient, value-driven supplychains have upstream companies been able tosurvive.Although it adds to the turmoil, the liftingof sanctions from Iran in early 2016 may behelping the downstream industry. Despite theEuropean market already being oversuppliedto the tune of 1.5m barrels a day, the arrivalof Iranian oil has served to further depressfeedstock prices and encourage in the processdeeper investment in petrochemical plantsacross the region.According to the association, the industry’sbiggest concern now is that feedstock pricesTAKING ADVANTAGE OFCHEAP FEEDSTOCKS,REFINERS HAVE MADE THEMOST OF LARGER PROFITMARGINS AND PRODUCINGHIGHER VALUE PRODUCTScontinue to stay at current levels. “Themajority of respondents see the lifting ofsanctions as having a positive affect forEuropean refineries Iranian crude offers acheap feedstock for refiners in the CEE regionwho saw record margins in 2015 and wouldlove to see this trend continue.”And that’s considered likely because Iranlooks like it will continue to pump crude intoa saturated European market.Making hay while the sun shines, oil andgas industry spokesmen report they are usingfatter margins from downstream businesses toput aside funds for the sprucing up of ageingassets in their upstream activities.The attempted coup in Turkey alarmed theregion’s entire energy sector. As a vital energytransit hub as well as an important and fastgrowing outlet for CEE countries, its longterm stability is considered vital throughoutthe EU. For example Romania, for whichTurkey is its biggest single export market, isalready suffering from the economic fall-outof the coup.On the bright side the region can onlybenefit from an end to the war in Syria andto conflicts with Islamic State that havedestabilised the Turkish market.Of the two major pipelines running throughTurkey, the one originating from Kirkuk innorthern Iraq has been severely affected bythe fighting.“Turkey plays a hugely influential rolewithin the region and is seen as a major playerin the downstream market,” points out theWorld Refining Association, citing its strategiclocation as a shipping hub and infrastructuresuch as the Star refinery under constructionon the Petkim Peninsula.If and when peace is restored, theCEE’s heavy current investments in theirdownstream activities could pay offhandsomely in the coming years.THE QUIET REVOLUTION: ENERGY IN THE CEE 11

OPPORTUNITYIN DIVERSITYUsing the capability, the financial means and a leadingregional market position in CEE, Hungary’s MOL see

Europe’s gas transit hub with the help of the Nord Stream pipeline that transports Russian natural gas to Western Europe underneath the Baltic Sea. This is a position Germany would cement if Nord Stream 2 were to go ahead. The CEE is concerned about the project, MUCH HAS BEEN ACHIEVED IN