Transcription

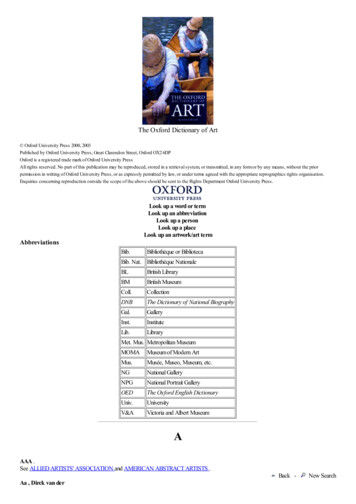

The Oxford Dictionary of Art Oxford University Press 2000, 2003Published by Oxford University Press, Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DPOxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University PressAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the priorpermission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation.Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department Oxford University Press.Look up a word or termLook up an abbreviationLook up a personLook up a placeLook up an artwork/art termAbbreviationsBib.Bib. Nat.BLBMColl.DNBGal.Inst.Lib.Met. Mus.MOMAMus.NGNPGOEDUniv.V&ABibliothèque or BibliotecaBibliothèque NationaleBritish LibraryBritish MuseumCollectionThe Dictionary of National BiographyGalleryInstituteLibraryMetropolitan MuseumMuseum of Modern ArtMusée, Museo, Museum, etc.National GalleryNational Portrait GalleryThe Oxford English DictionaryUniversityVictoria and Albert MuseumAAAA .See ALLIED ARTISTS' ASSOCIATION and AMERICAN ABSTRACT ARTISTS .Back Aa , Dirck van derNew Search

(1731–1809).The best-known member of a family of Dutch painters from The Hague. His speciality was grisaille decorative panels for interiors (examples inV&A, London). There was another van der Aa family of artists active in the 18th cent. in Leyden; most of the members were illustrators orengravers.Back New SearchAachen , Hans von(1552–1615).German painter, active in the Netherlands, Italy (1574–87), and most notably Prague, where he settled in 1596 as court painter to the emperorRudolf II (1552–1612). On Rudolf's death he worked for the emperor Matthias (1557–1619). His paintings, featuring elegant, elongated figures,are—like those of his colleague Bartholomeas Spranger —leading examples of the sophisticated Mannerist art then in vogue at the courts ofnorthern Europe, and he was particularly good with playfully erotic nudes (The Triumph of Truth , Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 1598). Engravingsafter his work gave his style wide influence and he ranks as one of the most important German artists of his time. He was married to Regina deLassus , daughter of the composer Orlando de Lassus (1532–94), who erected his tomb in St Vitus's Cathedral in Prague.Back New SearchAalto , Alvar(1898–1976). Finnish architect, designer, sculptor, and painter. One of the most illustrious architects of the 20th cent., Aalto was also a talented abstract painterand sculptor and an important furniture designer. In 1925 he married Aino Marsio , who was his chief collaborator until her death in 1949,particularly with the Artek furniture (first designed for the Paimio Sanatorium in 1928), whose new methods of bending and jointing andrevolutionary flowing lines became internationally popular and had a lasting influence on furniture design. During the period 1927 to 1954, butparticularly during the 1930s, Aalto engaged in what have been described as artistic laboratory experiments, making both abstract reliefs and freeabstract sculptures in laminated wood. These sculptural experiments, many of which were fine works of art in their own right, had the dual purposeof solving technical problems concerning the pliancy of wood in the manufacture of furniture and of developing spatial ideas which served as aninspiration for his architectural work, as in the Institute of International Education at New York (1965), where walls are conceived as abstractsculptural reliefs in wood. In the 1960s Aalto came to the fore as a monumental sculptor, working in bronze, marble, and mixed media.Outstanding among his monumental works is his memorial for the Battle of Suomussalmi, a leaning bronze pillar raised 9 m. on a stone pedestal setup in the arctic wastes of the battlefield (1960). Aalto was also influential in introducing modern art—particularly the works of Alexander Calderand Fernand Léger , his close friends—to the Finnish public.Back New SearchAaltonen , Wäinö(1894–1966).Finnish sculptor who came to be regarded as the personification of the patriotic spirit of his country in the years following the declaration ofindependence from Russia (1917). The bronze monument to the runner Paavo Nurmi (1925, the best-known cast is outside the athletics stadium inHelsinki) and the bust of the composer Sibelius (1928, various casts exist) are probably his most famous portrayals of national heroes.Back New SearchAbakanowicz , Magdalena(1930– ).Polish sculptor. She is the pioneer and leading exponent of sculpture made from woven fabrics and has been widely imitated in Europe and theUSA.Back New SearchAbbate , Niccolò dell'( c.1510–71).Italian painter. He was trained in the tradition of his birth-place, Modena, but he developed his mature style in Bologna (1547–52) under theinfluence of Correggio and Parmigianino . There he decorated palaces, combining painted stucco with figure compositions and landscapes (the bestsurviving examples are at the Palazzo Pozzi, now Palazzo dell' Università). His elegant figure style was influenced particularly by Parmigianino. Hewas invited to France in 1552, probably at the suggestion of Primaticcio , under whom he worked at Fontainebleau , and he remained in Francefor the rest of his life. Most of his work in the palace itself has been lost, and he is now considered most important for his landscapes with figuresfrom mythological stories (Landscape with the Death of Eurydice , NG, London). In these he was the direct precursor of Claude and Poussinand one of the sources of the long-lived tradition of French classical landscape.Back New SearchAbbey , Edwin Austin(1852–1911).American painter, etcher, and book illustrator, active and highly successful in England (where he settled in 1878) as well as his own country. Hespecialized in historical scenes and had several large and prestigious commissions, most notably a set of murals representing The Quest of theHoly Grail (completed 1902) in Boston Public Library (his friend Sargent also painted murals there) and the official painting commemoratingEdward VII's coronation in 1902 (Buckingham Palace, London). Such paintings now seem rather overblown and ponderous, and he is most highlyesteemed for his lively book illustrations. He was particularly prolific for Harper's Weekly , his association with the magazine lasting from 1870until his death.Back New SearchAbbot , Lemuel Francis( c.1760–1802).English portrait painter. His clientele included many naval officers and he is best known for his portrayals of Lord Nelson . He did several portraitsof him with slight variations (an example is in the NPG, London). In 1798 Abbot became insane, and his unfinished works were completed byother hands.Back New Search

Abildgaard , Nicolai Abraham(1743–1809).Danish Neoclassical painter. From 1772 to 1777 he studied in Rome, where his friendship with Fuseli helped to form his electic early style. On hisreturn to Denmark his work became more purely Classical, as is best seen in his cycles of paintings illustrating Apuleius and Terence (Statens Mus.for Kunst, Copenhagen). He became one of the leading figures in Danish art and had great influence because of his post as Director of theCopenhagen Academy (1789–91 and 1801–9), where his pupils included Runge and Thorvaldsen . Abildgaard occasionally worked as anarchitect, sculptor, and designer (most notably of some Grecian furniture for himself), and he also wrote on art. His most ambitious work, a hugedecorative scheme at Christianborg Palace, was destroyed by fire in 1794.Back New Searchabstract art .Art that does not depict recognizable scenes or objects, but instead is made up of forms and colours that exist for their own expressive sake.Much decorative art can thus be described as abstract, but in normal usage the term refers to 20th-cent. painting and sculpture that abandon thetraditional European conception of art as the imitation of nature. Herbert Read (Art Now , 1948) gave the following definition: ‘in practice we call“abstract” all works of art which, though they may start from the artist's awareness of an object in the external world, proceed to make a selfconsistent and independent aesthetic unity in no sense relying on an objective equivalence.’ Abstract art in this sense was born and achieved itsdistinctive identity in the decade 1910–20 and is now regarded as the most characteristic form of 20th-cent. art. It has developed into manydifferent movements and ‘isms’, but three basic tendencies are recognizable:i (i) the reduction of natural appearances to radically simplified forms, exemplified in the sculpture of Brancusi (one meaning of the verb ‘abstract’is to summarize or concentrate);ii (ii) the construction of works of art from non-representational basic forms (often simple geometric shapes), as in Ben Nicholson's reliefs;iii (iii) spontaneous, ‘free’ expression, as in the Action painting of Jackson Pollock . Many exponents of such art dislike the word ‘abstract’, butthe alternatives they prefer, although perhaps more precise, are usually cumbersome, notably non-figurative, non-representational, and NonObjective .The aesthetic premiss of abstract art—that formal qualities can be thought of as existing independently of subject-matter—existed long before the20th cent. In 1780, in his 10th Discourse to the students of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds advised that ‘we are sure from experiencethat the beauty of form alone, without the assistance of any other quality, makes of itself a great work, and justly claims our esteem andadmiration’; and in discussing the Belvedere Torso he referred to ‘the perfection of this science of abstract form’. In the 19th cent. several notablewriters followed this line (Maurice Denis , for example) and many of the leading painters of the 1890s—notably the Symbolists —stressed theexpressive properties of colour, line, and shape rather than their representative function. This process was taken further by the major avant-gardemovements of the first decade of the 20th cent.—especially Cubism , Expressionism , and Fauvism . By 1910, then, the time was ripe for abstractart, and it developed more or less simultaneously in various countries. Kandinsky is often cited as the first person to paint an abstract picture, butno artist can in fact be singled out for the distinction. (A work by Kandinsky known as ‘First Abstract Watercolour’ (Musée National d'ArtModerne, Paris) is signed and dated 1910, but some scholars believe that it is later and was inscribed by Kandinsky several years after itsexecution. This kind of problem arises not only with Kandinsky : several early abstract artists were keen to stress the primacy of their ideas andwere not above backdating works.) Among the other artists who produced abstract paintings at about the same early date as Kandinsky were theAmerican Arthur Dove and the Swiss Augusto Giacometti , cousin of Alberto Giacometti .The individual pioneers were soon followed by abstract groups and movements—among the first were Orphism and Synchromism in France.There was a particularly rich crop in Russia, with Constructivism , Rayonism , and Suprematism all launched by 1915. The almost religious fervourwith which some of the Russian artists pursued their ideals was matched by the members of the De Stijl group in Holland, founded in 1917. Tosuch artists, abstraction was not simply a matter of style, but a question of finding a visual idiom capable of expressing their most deeply felt ideas.In the period between the two world wars, the severely geometrical style of De Stijl and the technologically orientated Constructivism were themost influential currents in abstraction (they came together in the Bauhaus ), although Surrealism also had a strong abstract element. The firstinternational exhibition of abstract art was held in Paris in 1930 and there were many outstanding individual achievements in abstraction in thisperiod—the sculpture of Calder and Hepworth , for example. However, in general figurative art was dominant, and abstract art was banned intotalitarian countries such as Germany and Russia. The second heroic period of abstract art came after the Second World War, when theenormous success of Abstract Expressionism and its European equivalent Art Informel made abstraction for a time virtually the dominantorthodoxy in Western art.Back New SearchAbstract Expressionism .The dominant movement in American painting in the late 1940s and 1950s. It was the first major development in American art to lead rather thanfollow Europe, and it is often reckoned the most significant art movement anywhere since the Second World War. The energy and excitement itbrought to the American art scene helped New York to replace Paris as the world capital of contemporary art, and much of the subsequent historyof painting can be written in terms of reactions to it. The phrase ‘Abstract Expressionism’ had originally been used in 1919 to describe certainpaintings by Kandinsky , but in the context of modern American painting it was first used by the New Yorker art critic Robert Coates in 1945; bythe end of the decade it had become part of the standard critical vocabulary. The painters embraced by the term worked mainly in New York(hence the term New York School ) and there were various ties of friendship and loose groupings among them, but they shared a similarity ofoutlook rather than of style—an outlook characterized by a spirit of revolt against tradition and a demand for spontaneous freedom of expression.The stylistic roots of Abstract Expressionism are complex, but despite its name it owed more to Surrealism —with its stress on automatism andintuition—than to Expressionism . A direct source of inspiration came from the European Surrealists who took refuge in the USA during theSecond World War. The most famous Abstract Expressionist is Jackson Pollock , whose explosive energy best sums up the movement, but thework of other leading exponents was sometimes neither abstract (the leering Women of de Kooning ) nor expressionist (the serene visions ofRothko ). Even allowing for these wide differences, however, there are certain qualities that are basic to most Abstract Expressionist painting: thepreference for working on a huge scale; the emphasis placed on surface qualities so that the flatness of the canvas is stressed; the adoption of anall-over type of treatment, in which the whole area of the picture is regarded as equally important; and the glorification of the act of painting itself(see ACTION PAINTING ).

Alongside de Kooning , Pollock , and Rothko , the painters who are considered central to Abstract Expressionism include Gorky , Gottlieb ,Guston , Kline , Motherwell , Newman , and Still . Most of them struggled for recognition early in their careers, but during the 1950s themovement became an enormous critical and financial success. It had passed its peak by 1960, but several of the major figures continuedproductively after this. By 1960, also, reaction against the emotionalism of the movement was under way, in the shape principally of Pop art andPost-Painterly Abstraction . Sculptors as well as painters were influenced by Abstract Expressionism, the leading figures including Ibram Lassaw(1913– ), Seymour Lipton (1903–86), and Theodore Roszak (1907–81).Back New SearchAbstraction-Création .The name taken by a group of abstract painters and sculptors formed in Paris in February 1931, following the first international exhibition ofabstract art held there in 1930. It was successor to the group Cercle et Carré , founded in 1930. The group was open to artists of all nationalitiesand the organization was loose, so that at one time its numbers rose to as many as 400. As indicated by its title, the association was intended toencourage so-called ‘creative’ abstraction, by which was meant abstract works constructed from non-figurative, usually geometrical, elements(rather than abstraction derived from natural appearances, of the kind being developed by Roger Bissière among others in France). Theassociation operated by arranging group exhibitions and by publishing an illustrated annual with the title Abstraction-Création: Art non-figuratif ,which appeared from 1932 to 1936 with different editors for each issue. Within this general principle the association was extremely catholic in itsoutlook and embraced many kinds of non-figurative art, from the Constructivism of Gabo , Pevsner , and Lissitzky , and the Neo-Plasticism ofMondrian , to the expressive abstraction of Kandinsky , and even the biomorphic abstraction of Arp and some forms of abstract Surrealism .Owing, however, to the strength of the Constructivist element and the supporters of De Stijl , the emphasis fell increasingly upon geometrical ratherthan expressive abstraction. After c. 1936 the activitiesA French term for a private art school, several of which flourished in Paris in the late 19th and early 20th cents. The term ‘atelier libre’has alsobeen used to refer to such establishments. Entry to the official École des Beaux-Arts was difficult (almost impossible for foreigners, who from 1884had to take a vicious examin ation in French) and teaching there was conservative, so private art schools, with their more liberal regimes, wereoften frequented by progressive young artists. Four of them are particularly well known. The Académie Carrière was opened in 1890 by EugèneCarrière (1849–1906), a painter of portraits, religious pictures, and—his speciality—scenes of motherhood. His style was characteristically misty,monochromatic, and vaguely Symbolist . Rodin was a great admirer of his work. There was no regular teaching at the school, though Carrièrevisited it once a week. It was here that Matisse met Derain , thus helping to form the nucleus of the future Fauves . The Académie Julian wasfounded in 1873 by Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907), whose work as a painter is now forgotten. The school had no entrance requirements, wasopen from 8 a.m. to nightfall, and was soon the most popular establishment of its type. Julian opened several branches throughout Paris, one ofthem for women artists, and by the 1880s the student population was about 600. Although the Académie Julian became famous for the unrulybehaviour of its students, it was regarded as a stepping-stone to the École des Beaux-Arts (Julian had been astute in engaging teachers from theÉcole as visiting professors). Among the French artists who studied there were Bonnard , Denis , Matisse , and Vuillard . The list of distinguishedforeign artists who studied there is very long. The Académie Ranson was founded in 1908 by Paul Ranson (1864–1909), who had studied at theAcadémie Julian. After Ranson's early death, his wife took over as director, and his friends Denis and Sérusier were among the teachers. Amonglater teachers the most important was Roger Bissière , whose style of expressive abstraction influenced many young painters in the 1930s; hispupils included Manessier . The Académie Suisse was founded in about 1850 by a former artists’ model called Suisse ‘in an old and sordidbuilding where a well-known dentist pulled teeth at one franc apiece artists could for a small fee work from the living model without anyexaminations or tuition’ (John Rewald ,Back New SearchAcadémie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, Paris .See ACADEMY .Back New Searchacademy .Association of artists, scholars, etc., arranged in a professional institution. The original Academy was an olive grove outside Athens where Platoand his successors taught philosophy, and his school of philosophy was therefore known as ‘The Academy’. In the Italian Renaissance the wordbegan to be applied to almost any philosophical or literary circle and was sometimes employed of groups of artists who discussed theoretical aswell as practical problems—in this sense it was used somewhat ironically of Botticelli's studio c. 1500. Similarly the famous Accademia ofLeonardo da Vinci —the reference has come down to us in engravings of the first years of the 16th cent.—almost certainly implied no more th an agroup of men who discussed scientific and artistic problems with Leonardo. Another premature ‘academy’ is the one attributed by Vasari toLorenzo de’ Medici under the direction of the sculptor Bertoldo , a suitable ancestor for the one that Vasari himself promoted in 1563; all theevidence suggests that while Lorenzo allowed artists and others easy access to his collections, there was no organized body of any kind concernedwith the arts in the Florence of his day. Finally, there is an engraving of 1531 by Agostino Veneziano (1490–1540) which shows the Accademiadi Baccio Bandin in Roma in luogo detto Belvedere . Although this portrays sculptors drawing a small statue in Bandinelli's studio, it probablyrepresents no more than a group of friends discussing the theory and practice of art.The first art academy proper was set up some 30 years later when Duke Cosimo de' Medici founded the Accademia del Disegno in Florence in1563. The prime mover was Giorgio Vasari , whose aim was to emancipate artists from control by the guilds, and to confirm the rise in socialstanding they had achieved during the previous hundred years. Michelangelo , who more than any other embodied this change of status in his ownperson, was made one of the two heads and Duke Cosimo himself was the other. Thirty-six artist members were elected, and amateurs andtheoreticians were also eligible for membership. Lectures in geometry and anatomy were planned, but there was no scheme of compulsory trainingto replace authority, but in Florence itself it soon degenerated into a sort of glorified artists' guild.The next important step was taken in Rome, where in 1593 was founded the Accademia di S. Luca, of which Federico Zuccaro was electedpresident. Though more stress was laid on practical instruction than at Florence, theoretical lectures were also prominent in the Academy's plans.However, the Academy was not at all successful in its war against the guilds until the powerful support it received from Pope Urban VIII (MaffeoBarberini ) in 1627 and 1633. Thereafter it grew in wealth and prestige. All the leading Italian and many foreign artists in Rome were members;debates on artistic policy were held; some influence over important commissions was wielded; and everything was done to make the lives of thosewho were not members (such as many of the Flemish freelance artists working in Rome—see FIAMMINGO ) as unpleasant as possible.

The only other similar organization in Italy was the Academy established in Milan by Cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1620. But meanwhile theword was very frequently used of private institutions where artists met either in a studio or in some patron's palace to draw from life. The mostfamous example of this kind was organized by the Carracci in Bologna.In France a group of painters, moved by the same reasons of prestige as had earlier inspired the Italians, persuaded Louis XIV (1638–1715) tofound the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1648. Here too the guilds put up a powerful opposition, and its supremacy was notassured until Colbert was elected Vice-Protector in 1661 and found in the Académie an instrument for imposing the official standards andprinciples of taste. Colbert and Lebrun , the Director, envisaged dictatorship of the arts, and for the first time in history the expression ‘academicart’ acquired a precise significance. The Académie arrogated to itself a virtual monopoly of teaching and of exhibition, and by applying rigidly itsown standards of membership came to wield an important economic influence on the profession of artist. For the first time an orthodoxy of artisticand aesthetic doctrine obtained official sanction. Implicit in the academic theory and teaching was the assumption that everything to do with thepractice and appreciation of art, or the cultivation of taste, can be brought within the scope of rational understanding and reduced to logicalprecepts that can be taught and studied.Other art academies were founded in Germany, Spain, and elsewhere between the middle and end of the 17th cent., and it has been calculatedthat in 1720 there were nineteen of them active in Europe. An upsurge of activity occurred in the middle of the 18th cent., and by 1790 well over ahundred art academies were flourishing throughout Europe. Among these was the Royal Academy in London, which was founded in 1768(previously in England there had been only private teaching academies, one of which was run by Thornhill and then by Hogarth ). For the most partthese academies were the product of a new awareness on the part of the State of the place that art might be expected to p Baroque and Rococo .Everywhere the academies made themselves the champions of the new return to the antique . As far as instruction went, the copying of casts andlife drawing were paramount, and Classical subjects were particularly encouraged.There was some opposition to these bodies from the start. Towards the end of the 18th cent. French Revolutionary sentiment was especially bitterabout the exclusive privileges enjoyed by members of the Académie, and many artists, with David in the lead, demanded its dissolution. This stepwas taken in 1793, but after various experiments had been tried and substitute bodies set up, the Académie was reinstated in 1816 as theAcadémie des Beaux-Arts.In fact the real threat to academies came rather from the Romantic notion of the artist as a genius who produces his masterpieces by the light ofinspiration which cannot be taught or subjected to rule. Opposition was accentuated by the widening breach between creative artists and thebourgeois public after aristocratic patronage declined.Virtually all the finest and most creative artists of the 19th cent. stood outside the academies and sought alternative channels for exhibiting theirworks, although Manet , for example, always craved traditional academic success. When the revaluation of 19th-cent. art took place with the finalrecognition of the Impressionists this contrast was too blatant to be ignored. Academies were condemned out of hand by the adventurous, thoughthey still retained prestige among those who were too confused by the prevailing breakdown of taste to risk supporting what they did notunderstand. Gradually compromises were made on both sides, facilitated by the liberalization of the academies and the increasing number of artschools which have finally broken academic monopolies. Academies now generally hold the view that they should at least insist on certainstandards of sheer craftsmanship which any artist, however personal his vision, is expected to display. During the 20th cent. the pace hasquickened. Most of the aesthetic movements, however revolutionary they seemed at the time, have rapidly produced their own ‘academicism’asminor artists of no more than moderate endowment have aped the mannerisms of the few geniuses who have shaped each movement. Thus, theword ‘academic’now almost always carries a pejorative meaning, and is associated with mediocrity and lack of originality. Virtually all the finestand most creative artists of the 19th cent. stood outside the academies and sought alternative channels for exhibiting their works, although Manet,for example, always craved traditional academic success. When the revaluation of 19th-cent. art took place with the final recognition of theImpressionists this contrast was too blatant to be ignored. Academies were condemned out of hand by the adventurous, though they still retainedprestige among those who were too confused by the prevailing breakdown of taste to risk supporting what they did not understand. Graduallycompromises were made on both sides, facilitated by the liberalization of the academies and the increasing number of art schools which have finallybroken academic monopolies. Academies now generally hold the view that they should at least insist on certain standards of sheer craftsmanshipwhich any artist, however personal his vision, is expected to display. During the 20th cent. the pace has quickened. Most of the aestheticmovements, however revolutionary they seemed at the time, have rapidly produced their own ‘academicism’ as minor artists of no more thanmoderate endowment have aped the mannerisms of the few geniuses who have shaped each movement. Thus, the word ‘academic’ now almostalways carries a pejorative meaning, and is associated with mediocrity and lack of originality.Back New Searchacademy board .A pasteboard used for painting, especially in oils, since the early 19th cent. It is made of sheets of paper sized and pressed together, and treatedwith a ground consisting usually of white lead, oil, and chalk. Sometimes it is embossed with indentations—a sort of mechanical ‘grain’—inimitation of canvas weave. Because it is fairly inexpensive, academy board is a popular support with amateur painters, and it is also used byprofessional artists for sketches and studies.Back New Searchacademy figure .A careful painting or drawing (usually about half life-size) from the nude made as an exercise. The figure is usually depicted in a heroic pose, andthere is a tradition of suitable postures which goes back to the Carracci . An academy figure ascribed to Géricault is in the National Gallery,London.Back New SearchAccademia di Belli Arti, Venice .The municipal picture gallery of Venice and one of the most important collections in Italy. It was founded by decree of Napoleon in 1807 andcombined the collection of the old Academy, the Galleria dei Gessi founded in 1767, with works of art from suppressed churches and monasteries.The collection has continually been enriched by additions, in particular Venetian paintings returned after the fall of Napoleo

OED The Oxford English Dictionary Univ. University V&A Victoria and Albert Museum A AAA . See ALLIED ARTISTS' ASSOCIATION and AMERICAN ABSTRACT ARTISTS . Back - New Search Aa , Dirck van der (1731–1809). The best-known member of a family of Dutch painters from The Hague. His speciality w