Transcription

Timber ManualDatafile P1TimberSpecies andPropertiesRevised Edition2004

ContentsIntroduction.2Wood Structure .3Sapwood and Heartwood .3Softwoods and ure .4Properties.4Density .4Moisture Movement .4Moisture Content.4Durability of Heartwood .5Strength .6Fatigue Effect .7Temperature Effect .7Preservative Treatment Effect .7Joint Strength .7Hardness .7Thermal Properties .8Electrical Conductivity.8Chemical Resistance .8Corrosive Action .9Acoustic Properties .9Utilisation.9Grading.9Weathering .9NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesThe Timber SpeciesProperties Schedule .9-17Cover Photo: Whether it be structural ordecorative, timber selection must take intoaccount the properties and appearancecharacteristics of species.This revised edition of Timber Manual Datafile P1 was supported inpart with funding from the Forest and Wood Products Research &Development Corporation (FWPRDC).The Corporation is jointly supported by the Australian forest and woodproducts industry and the Australian Government.The information, opinions, advice and recommendations containedin this Datafile have been prepared with due care. They are offeredonly for the purpose of providing useful information to assist thoseinterested in technical matters associated with the specification anduse of timber and timber products. While every effort has been madeto ensure that this Datafile is in accordance with current technology,it is not intended as an exhaustive statement of all relevant data, andas successful design and construction depends upon numerous factorsoutside the scope of the Datafile, the National Association of ForestIndustries Ltd accepts no responsibility for errors or omissions fromthis Datafile, nor for specification or work done or omitted to be donein reliance on this Datafile. NAFI — 1989, 2004ISBN — 1 86346 006 3, ISBN — 1 86346 021 72IntroductionTimber is one of man’s oldest building materials. It is arenewable, naturally occurring organic polymer, uniquein a world of synthetic and composite building materials.Today, timber is derived from sustainably managedforests and is one of our most environmentally friendlybuilding materials. The wide distribution of timber, itsready availability, variety of uses and relative ease ofhandling and conversion, have all contributed to its wideacceptance in the building industry.The small tubular cells that are the fundamentalstructural elements of solid wood give timber its goodproperties for sound, electrical and heat insulation, forengineering requirements, and strong aesthetic appeal.Because of its wide range of properties, it is essentialthat for a particular application, the most suitable timberspecies is selected.A sound understanding of tree growth and timberproperties, combined with skilful forest management,ensures that we can reliably plan to meet these futuretimber demands, while building a world-competitiveforest and forest products resource.An essential first step in generating fit-for-purposetimber products is the selection of appropriate timberspecies. There are more than 30,000 tree speciesthroughout the world, producing timber with a widerange of properties. In its natural solid form, or inreconstituted or engineered products, timber hasproperties that will meet the specified requirements for awide range of applications.Pages 10 to 17 of this Datafile present the TimberSpecies Properties Schedule, a full listing of thepoperties of the timber from over 60 species of tree.Species properties may also be modified by specialtreatments that, for example, increase the decayresistance, surface hardness and dimensional stability oftimber products.The wide range of properties available from timberprovides the designer with an almost unlimited choicefor both structural and decorative applications.The timber industry has a network of advisory servicesthroughout Australia to help timber users, specifiers/architects, builders and regulators make the mostappropriate selection of timber products.These services are listed at the end of this Datafile.Weatherexposedapplicationsrequire selectionof suitable,durable speciessuch as inthis outdoorrestaurant deckand pergola

Natural grainand colourof timberenhancesbuildinginterior.sapwood thickness is only about 2-5 cm in radial width.Comparisons of sapwood and heartwood show that: sapwood and heartwood, at equivalent moisturecontents, are equally strong and weigh about thesame. sapwood has lower natural decay resistance(durability) than heartwood, but generally acceptspreservatives more readily. sapwood is usually lighter in colour than heartwood,however, in some species, there is little difference.(Note: The durability ratings of a species published in thisDatafile is based on that of the outer heartwood.)Sapwood and HeartwoodThe structure of a tree stem can be broadly divided intotwo main zones. When viewing the end-section of a logor cross-section of a tree stem, the central wood zone,is usually considerably darker than the portion adjacentto the bark. Generally, the light coloured wood is thesapwood remainder. (See Figure 1) The discolourationor darkening of the heartwood zone is due to theproduction and secretion of substances that are byproducts of the living processes in the tree.The tree grows in thickness by producing new wood,or outer sapwood just under the bark, while the innersapwood, adjacent to the heartwood, is in the process ofbeing converted into heartwood. This means that oncea tree reaches a steady stage in its growth pattern, thethickness of the sapwood remains fairly constant. Theby-products that cause the darkening of the heartwoodare termed extractives and these are laid down by thetree as the inner sapwood cells die and are convertedinto heartwood. The heartwood itself can be dividedinto inner- and outer-heartwood. The extractives havea marked influence on timber properties, particularlydurability. The proportion of sapwood to heartwoodvaries depending on species and growth conditions. Insoftwoods (see below), like radiata pine, the sapwoodconstitutes a considerable portion of the log volume,while in hardwoods (see below), like the eucalypts, theFigure 1: Tree cross-sectionSoftwoods and HardwoodsThe terms “softwood” and “hardwood” do not indicatesoftness or hardness of particular timbers. Thesoftwoods come from the coniferous (cone-bearing)species such as the pines, spruces and Douglas fir(Oregon). The hardwoods come from the broadleavedgroup of species such as the eucalypts, oaks, andmeranti. Many hardwoods are softer and lighter thansome softwoods, e.g., balsa, paulownia.NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesWood StructureThe wood cells of a tree can be divided into those thatgive the timber its strength and general structure, andthose that conduct liquids, such as water and nutrients,through the tree during its growth.Fibres are the structural elements that make up 30-80%of the volume of timber in hardwoods, and tracheids arethe structural elements that constitute about 90% of thevolume of timber in softwoods.The conductive cells in hardwoods are vessels (alsocalled pores) and rays, while softwoods possess rays butnot vessels. Vessels allow liquid flow longitudinally upand down the tree while rays facilitate lateral flow acrossthe tree stem. The arrangements of the various woodcells in the overall structure of timber vary from onespecies to another and define the various properties andcharacteristics of the final timber products.Colourvariationsbetweensapwood andheartwoodadd characterto ceilingpanellingLight colouredsapwoodcontrasts withheartwood incypress pineflooring3

All unfinishedtimber turnsgrey if exposedto weatherAppearancePropertiesColourDensityMost timbers show variation in colour between speciesand within species. Colour descriptions usually relate tothe heartwood of the species and may be significantlydifferent from that of the sapwood. Colour may alsovary during use and can be influenced by the applicationof different finishes. Timber exposed to light will changecolour and unprotected timber, exposed to the weather,will eventually become silvery grey in colour.GrainGrain refers to the general direction, size andarrangement of the wood cells (discussed above),and may be used to broadly describe the timber’sappearance. However, the word “grain” when used alonemay not be sufficiently specific. It is more appropriateto use such descriptive terms as straight grain, slopinggrain, spiral grain, irregular grain, wavy grain, and thelike, which describe some specific characteristics of thetimber grain.NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesNatural figureenhancesveneer panelledwalls in publicplaces such asrestaurantTextureThe timber’s texture may be described as being coarse,fine, even or uneven. This differentiation between coarseand fine texture is made on the basis of the size andarrangement of the wood cells. Softwoods are normallyconsidered to be fine textured, whereas hardwoods mayspan the range from coarse to fine. Mountain ash is anexample of a coarse textured hardwood but brush box,also a hardwood, is considered to have a fine texture.FigureFigure means the patterns produced on the surfaceof timber, and is influenced by the arrangement anddimensions of the wood cells, the nature of the grain,and colour variations in the heartwood and sapwood.Figure may also depend on whether logs are quartersawn or back sawn. Interlocked and wavy grain createa striking figure, due to the manner in which light isabsorbed or reflected at differing angles by the woodcells.Density of timber at a specific moisture content is theamount (mass) of wood substance in a given volume,expressed as kilograms per cubic metre.Density is influenced by the amount of wood cell wallrelative to the amount of void space in and betweenthe cells. The density of the wood cell wall (fibres,tracheids, vessels, or rays) is constant in all timberspecies at 1400-1500 kg/m3 Thus, the main factorsaffecting density are the size of the cells (includingcell wall thickness), the amount of void spaces, and theproportions and distribution of the different cell types.In general terms, density is one of the most reliableindicators of strength, as well as several other properties,such as stiffness, joint strength, hardness, ease ofmachining, fire resistance and drying characteristics.Density can be given in at least one of three forms.Density is greatly influenced by the amount of moisturecontained in the timber at the time of measurement.For that reason, density values are normally quotedat a standard moisture content of 12 per cent. This isreferred to as the air-dry density. Sometimes the termbasic density may also be used. It is defined as the massof oven-dry wood divided by its green volume. In thiscase, it is a green density value. Approximate densitiesfor unseasoned timber are set out in the Timber SpeciesProperties Schedule at the end of this Datafile.Moisture MovementAs wood dries below its fibre-saturation point, it shrinks.However, the loss in dimension is not the same in alldirections. The longitudinal shrinkage, that is, the lengthof timber of product, is very small and usually may bedisregarded.In the radial direction, (across a piece of timber)depending on species, shrinkage is around 3% to 6%when drying down to 12% moisture content. In thedirection of the growth rings, ie: tangentially, theshrinkage is generally about twice this amount, 6%to12%.Moisture ContentBecause living trees contain sap, newly felled timberusually has a high moisture content. Moisture content(MC) is the mass of water contained in the wood,expressed as a percentage of the mass of oven-dry wood.When the moisture content is between zero and about4

Equilibrium moisture content (emc)of wood (%)Figure 2: Equilibrium moisture content (emc)Relative HumidityFigure 3: Effect of shrinkageIf seasoned timber is used, the direction of cut isusually not as important since there should be no largesubsequent change in dimension.For some structural applications, it may be necessary touse large sections of unseasoned timber. In these cases,it is essential to limit the effects of shrinkage by carefuldesign. The possibility of differential shrinkage betweenadjacent members should be avoided. (Refer to DatafileP4 - Timber – Design for Durability for additionalinformation.)Additional techniques considered to be good practice tominimise the movement effects due to moisture changes,are: select timbers with low movement characteristics. protect against excessive drying or wetting. apply a coating to the timber that will retard rapidmoisture absorption or loss. use smaller rather than larger cross-sections.The term “movement” is used to describe the periodicsmall dimensional changes that occur in seasoned timberdue to environmental changes. This movement maybe either shrinkage or swelling and its basic cause is achange in the moisture content of wood occurring belowthe fibre saturation point.The usual way of minimising the likelihood of anyadverse effects is to ensure that the timber member whenfirst installed is at a moisture content approximatelymid-way between the extremes of the equilibriummoisture content it is likely to attain in service. Internalflooring, for example, would probably need to beinstalled with its moisture content at around 12%.Seasoned timber has a moisture content between 10%and 15%, and its use has several advantages including: cross-section dimensions remain almost constant. weight is reduced. strength is improved. electrical resistance is increased. gluing and nail holding properties are improved. joint strength is increased.Durability of HeartwoodIn general, there are two main factors, which influence atimber’s in-service performance. The first is the naturaldurability of the particular species, while the otherrelates to the type and degree of hazard to which thetimber is exposed.Durability is expressed in terms of one of four classes,which have been based on a combination of field trialsfor untreated heartwood both in the ground and abovethe ground (when ventilation and drainage are adequate),expert opinion, and experience of timber in service.Class 1 timbers have the highest level of naturaldurability and are expected to be resistant to decay andtermite attack for at least 25 years.The durability rating reflecting natural durability, relatesto the resistance of outer heartwood of the species tofungal and insect (termite) attack. Note that sapwood isdeemed not to be durable unless it has been treated withsome form of preservation material.5NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and Properties25%, moisture is totally contained within the cell walls,but in the range from 25% MC to 35% MC (dependingon the species), the cell walls become saturated; andthis is called the fibre-saturation point (FSP). Above thefibre-saturation point, additional moisture is held as freewater in the cell cavities.Timber releases or absorbs moisture in response tochanges in relative humidity until the moisture contentof the timber has stabilised at an equilibrium moisturecontent (EMC). Assuming a constant temperature, theultimate moisture content that a given piece of timberwill attain, expressed as a percentage of its oven-dryweight, depends upon the relative humidity of thesurrounding atmosphere. (See Figure 2.)Moisture content within living trees varies greatly.Moisture content may range from 30% in the heartwoodof some hardwoods and Douglas fir, to 200% in thesapwood of some low density timbers. Generally, timberwhich has a moisture content exceeding 15% is regardedas unseasoned.The effect of shrinkage on timber sections cut fromvarious sections of a log, is shown in Figure 3. Thiseffect may only be of major significance to the end-userwhen unseasoned timber is used and is allowed to dry inplace.

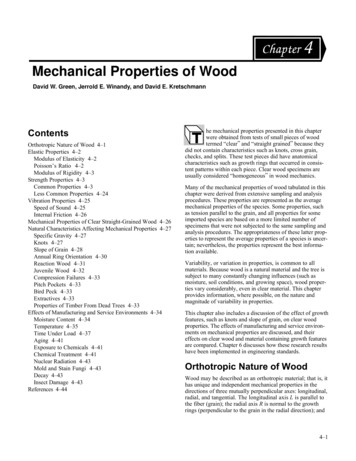

Durable timberselected forexposedtropicalenvironment.The Classes are only a guide to expected performance;they should not be used as definitive prescriptions. (Fordurability of Australian timbers see the Timber SpeciesProperties Schedule.)The serviceability of timber may also be affected byborers, termites, or marine borers. Note that termiteresistance may not be the same as decay resistance andthis is listed separately in national Standards for timbersthat are used inside and above the ground. AS56042003 Timber – Natural Durability Ratings, lists bothin-ground and above-ground life expectancies and thetermite resistance of timbers when used inside.Good design workmanship, finishing and maintenanceare helpful, together with the selection of species of highnatural durability where necessary. An alternative is theuse of timber that has been treated with some form ofpreservative. (Further discussion about durability can befound in Datafile P4 - Design for Durability.)NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesStrengthThe strength of timber is described in terms of “stressgrades”. A stress grade is defined in the AS1720 SAATimber Strutures Code, as the classification of timberfor structural purposes. It is based on either visual ormachine grading, which indicates the basic workingstresses and stiffnesses that apply to timber productsused for structural design purposes. The stress grade isdesignated in a form such as F7, which indicates thatfor such a grade of timber , the basic working stress inbending is approximately 7 MPa.When timber is graded by visual means the resultingstress grade is influenced by both the inherent strengthof the species concerned and the quality (or grade)of the particular parcel of timber. Grade descriptionsare listed in Australian Standard specifications forstructural timber, which places limits on the size orextent of strength reducing characteristics, such asknots or sloping grain. The two main Standards are AS2082 Timber – Hardwood - Visually Stress-Graded forStructural Purposes and AS 2858 Timber - Softwood– Visually Stress-Graded for Structural Purposes.The inherent strength of timber species (strength group)is scheduled in Appendix A. There are seven strengthgroups (S1 to S7, with S1 being the strongest) forunseasoned timber and eight (SD1 to SD8) for seasonedtimber.The relationship between these strength groups, thevisual grades and the resulting stress grades is illustratedin Table 1.An exception to the general rule is cypress pine. Theappropriate stress grades for cypress pine are F4, F5 andF7. For further information refer to AS2858.Stress grades may also be determined by mechanicalgrading to deliver: machine stress grading; and proof gradingMachine stress grading utilises a computer-controlledmachine which is usually limited to production centreswith large throughputs. The basis of the technique is thatstiffness can be directly correlated to strength.Table 1: Strength group/stress grade/visual grade relationshipStrengthGroupStructural No.2Stress GradeStructural F22F17F14F11F8F34F27F22F17F14F11F8F7Structural No.1Unseasoned TimberS1S2S3S4S5S6S7Seasoned TimberSD1SD2SD3SD4SD5SD6SD7SD8Structural No.4Structural No. 4Note: Structural grade no.5 applies to softwood only - as specified in AS28256

Individual pieces are fed into the machine in alongitudinal direction and continually deflected in thenarrow dimension by a given load. A coloured sprayindicates the stress grade of the piece, based on ameasure of the resulting deflection.Machine Graded Pine (MGP), used to designate stressgrades for seasoned softwoods like radiata, slash, hoop,and other pines, is now widely available in the framinggrades MGP10, 12, and 15. These grades satisfy therequirements of stress grades F5, F8 and F11 seasonedtimber, respectively.Proof grading allocates a stress grade to a piece oftimber if it demonstrates its ability to sustain a specificproof bending stress. The proof stress applied isgenerally from 2.2 to 2.4 times the actual design stress.The load is applied on edge to simulate the usual loadingmethod in service.Fatigue EffectUnlike most structural materials, timber is very resistantto cyclic loading, as occurs with structures subjectedto high wind loads or vibrating machinery. Allowableworking stresses for loads of long duration are safe formost structures subjected to impact or cyclic loading,but designers should determine the magnitude andfrequency of cyclic loading and consider them in design.Sustained loading produces a time-dependent behaviourof timber known as creep, and allowance for this effectis made in AS1720 SAA Timber Structures Code.Standard static tests show that wood subjected to 30million cycles of stress in tension parallel to the grainretains 40% of its static strength. In joints, considerationmust be given to cyclic effects on metal connectors.Timberstructuresand claddingperform wellin a coldalpineenvironments.Preservative Treatment EffectCurrent commercial preservative treatments have littleeffect on the strength of timber. Allowable workingstresses are the same as for untreated timber. It should benoted that timber treated with water-borne preservativesthat has not been re-dried after treatment should beregarded as unseasoned timber for grading purposes.Where the timber is re-seasoned after treatment it mayneed to be re-graded.Joint StrengthFor the purpose of joint design, all species have beenclassified into six ‘joint groups’ - J1 to J6 - for theunseasoned condition, and six groups JD1 to JD6 forthe seasoned condition. The Timber Properties Scheduleat the end of this Datafile shows the joint groups forindividual species.Where test data is not available for a particular species,a joint group may be established in relationship to aspecies density. Table 2 provides minimum averagedensities appropriate to each joint group.HardnessHardness of wood refers to its resistance to wear orabrasion and it’s resistance to indentation. It is alsoreflected in the difficulty of sawing and planing thetimber. Hardness is measured by the load required toembed a defined-sized ball to one half its diameter intothe wood. The figures given in the Timber PropertiesSchedule refer to this resistance to indentation, whichgenerally is considered to be an indicator of the otherhardness factors.NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesStress gradingpermitsengineered trussdesign usingsmall membersizes.Temperature EffectThe strength of timber is affected by temperature. Ingeneral, the mechanical properties of wood decreasewhen it is heated and increase when it is cooled. Atbelow freezing temperatures, strength values for bendingand compression, and for resistance to shock, areslightly higher than for values at normal temperatures.Timber subjected to very high temperatures can beweakened, but allowable working stresses are safe fortimber exposed to temperatures up to approximately40oC. Above that, stresses should be reduced.The combination of high temperature and high humidityin structures such as indoor swimming pools will needto be considered. Reference should be made to Clauses2.5.2 and 2.5.3 of AS 1720.1 SAA Timber StructuresCode.Table 2: Density/joint group relationshipUnseasoned TimberJoint GroupBasic Densitykg/m3J1750J2600J3475J4380J5300J6240Seasoned TimberJoint GroupJD1 JD2 JD3 JD4 JD5 JD6Air-dry940 750 600 475 380 300Density at12% mc kg/m3NOTE: Basic density is the mass of an oven-dry specimendivided by its volume when unseasoned.7

NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and PropertiesThermal PropertiesCompletely dry wood expands with heat and contractson cooling. The thermal expansion of wood is generallyinsignificant. When thermal expansion does occur, it isabout 5 to 10 times greater across the grain than along it.Consequently, thermal expansion in timber structures isseldom a consideration.For very long spans, such as in bridges or large floorareas, expansion should be calculated, taking theoffsetting effect of shrinkage into account. Expansionjoints should be provided if warranted.The thermal conductivity of wood is low, so timber canbe viewed as a natural insulator. Air pockets within thewood’s cellular structure make it a natural barrier toheat and cold. Since thermal conductivity increases withdensity, light-weight timber is a better insulator thandense timber. Thermal conductivity varies slightly withmoisture content, residual deposits in the timber suchas the extractives, and natural characteristics, such aschecks, knots and grain direction.An advantage of timber-framed construction is thatadditional insulating materials can be placed in thespaces between framing members without increasingwall, ceiling, roof or floor thickness.Some preservative treatments, e.g. copper chromiumarsenic (CCA), in the presence of moisture can corrodeunprotected fittings and fixings such as mild or brightsteel nails and screws. It is important under theseconditions to ensure that the fittings and fixings are ofresistant materials, such as hot-dipped galvanised nailsand screws. Further information on this can be found inDatafile P4 - Timber - Design for Durability.Aluminium, copper, brass, bronze and galvanised steelare much more resistant than bright steel to wood acidssuch as acetic acid. When the pH of wood is below 4.3the rate of corrosion of steel increases considerably.Table 3 provides pH values for a range of species. Amore comprehensive list may be found in Wood inAustralia by K.R. Bootle.Electrical ConductivityThe electrical resistance of timber varies greatly withits moisture content, from many thousands of megohmswhen very dry to near zero at the fibre-saturation point;electric moisture metres utilise this properly to measurethe moisture content of timber.In the moisture ranges where timber is a good insulator(poor conductor), moisture metres are reasonablyaccurate. However, timber becomes a good conductorat and above the fibre-saturation point, meaning thatresistance moisture metres cannot be used in thisrange with accuracy. Other metres, based on electriccapacitance, can be used in these cases.As a conductor, timber can be heated by subjecting it toa high-frequency electrical field. Some adhesives can beheat-cured by this process during laminated timber orplywood manufacture.Seasoned timber is normally regarded as a nonconductor for most practical purposes. Note however,that timber containing high levels of water-solublesalts from some preservatives and fire-retardants orthrough prolonged contact with seawater, may undergo8Timberstructuresare idealfor indoorswimmingpools.an increase in conductivity when the moisture contentexceeds about 12%.Chemical ResistanceTimber offers considerable resistance to buildingattack by a wide variety of chemicals including organicmaterials, hot or cold solutions of acids or neutral salts,and dilute organic and mineral acids. Direct contactwith caustic soda should be avoided. Strong acids andalkalies will destroy timber in time but the action isnot rapid, with alkaline chemicals more likely to causecellular degradation than acidic ones.In general, heartwood is more resistant to chemicalattack than sapwood, because of its relative resistanceto liquid penetration. Resistance to chemical attackis greater in softwoods than in hardwoods due tosoftwoods usually having a lower hemicellulose andhigher lignin content.Resin in some softwoods, such as Douglas fir and slashpine, shows good resistance to chemicals if free ofsapwood. The benefit of resisting chemical attack shouldbe balanced against the practical difficulties of havingpreservation material penetration into softwoods.Because of the properties identified above, timber iscommonly used to manufacture vats and tanks forchemical storage or for structural members in factorieswhere corrosive vapours are present.Further information can be found in Datafile P4 Timber - Design for Durability.Table 3: Timber – pH valuesSpeciespH Valueash, alpineblackbuttbox, brushfir, Douglasgum, spottedironbarkjarrahkapurmeranti, red, lightmerbaupine, cypress, whitepine, hooppine, 74.3-6.14.35.75.24.0-4.8

WeatheringCorrosion of metals by wood can sometimes occur whenthe wood is wet or is used unseasoned. This is related tothe timber’s conductivity (see previous page for moredetails on this subject). Examples may be seen where theextractives in moist wood have reacted with bright steelnails and caused dark coloured corrosion products to b

ISBN — 1 86346 006 3, ISBN — 1 86346 021 7 NAFI Timber Manual Datafile P1 - Timber Species and Properties 3 Introduction Timber is one of man’s oldest building materials. It is a renewable, naturally occurring organic polymer, unique in a world of synthetic and composite building materials. Today,