Transcription

A RESOUR CE G UI DE TOENGAG I NG EMP LOYER SBy Randall Wilson JANUARY 2015

Jobs for the Future works with our partners toAccelerating Opportunity seeks to changedesign and drive the adoption of education andthe way Adult Basic Education is delivered bycareer pathways leading from college readiness toputting students on track to earn a postsecondarycareer advancement for those struggling to succeedcredential and providing them with the supportin today’s economy.needed to succeed. The initiative targets workersWWW.JFF.ORGwho are underprepared for today’s demanding jobmarket and builds on the legacy of JFF’s innovativeadult education initiative Breaking Through, as wellas Washington State’s I-BEST program. AcceleratingOpportunity is supported by a strategic partnershipof five of the nation’s leading philanthropies.WWW.ACCELERATINGOPPORTUNITY.ORGACK NOW LE D GME N T SThis resource guide was made possible with the generous support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,the U.S. Department of Labor, The Joyce Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, The Kresge Foundation,the Open Society Foundations, the Arthur Blank Foundation, the Woodruff Foundation, the CaseyFoundation, and the University of Phoenix Foundation. Barbara Endel, program director at Jobs for theFuture, provided critical guidance in conceiving and improving this guide. Maria Flynn, senior vice presidentat JFF, and Navjeet Singh, deputy director of the National Fund for Workforce Solutions, also reviewed andoffered comments. Erica Acevedo, JFF program manager, provided invaluable research assistance. We alsowant to thank members of the Accelerating Opportunity coaching staff for their contributions and input:Israel Mendoza, consultant; Nan Poppe, consultant; Darlene Miller, executive director, National Council forWorkforce Education; and, at JFF, Rachel Pleasants McDonnell, senior program manager; Alexandra Waugh,senior program manager; and Nate Anderson, program director. On the JFF communications team, SophieBesl, project manager, communications, and Rochelle Hickey, graphic designer, provided editorial anddesign support.COPYRIGHT 2014 Jobs for the FuturePHOTOGRAPHY 2010 Mary Beth Meehan

TA BLE OF CON T E N T SA RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERSWhy Engage Employers?12LEVEL I: ADVISING6LEVEL II: BUILDING EDUCATIONAL CAPACITY8LEVEL III: CO-DESIGNING CURRICULA ANDCAREER PATHWAYS10LEVEL IV: CONVENING WORKFORCE PARTNERSHIPS13LEVEL V: LEADING AND SUSTAINING REGIONALPARTNERSHIPS15CONCLUSION17REFERENCES19

ivA RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

A R E S O UR CE GUI D E TOE N GAG I NG E MPLOYE R SThis resource guide presents working models of successful employerengagement and lessons for securing and sustaining partnerships withemployers. It was written to help education and training providers fullyrealize the value of strategic, long-term, and intensive partnershipswith employers. While directed to community colleges and theirstate-level partners in Accelerating Opportunity, it is relevant to allpractitioners in workforce, career, and technical education, and adulteducation.To develop this guide, the author researched current literatureon employer engagement, with a particular focus on partnershipsbetween community colleges and employers. We looked for thebest examples that have a demonstrated track record—especiallyones mentioned in multiple sources—and that are relevant to theadvancement of lower-skilled and/or lower-income adult workers.There are a number of useful frameworks and models in circulation;this resource guide draws on and synthesizes them to provide acompact introduction for staff in community colleges and workforceprograms. (See References for a full listing.)This guide responds to a mismatch between the demand and supplysides of the labor market. While there is considerable effort on thepart of the workforce community, in colleges and elsewhere, toconnect to employers and provide the best-skilled job candidates,those efforts do not always translate into results valued byemployers. This mismatch is well illustrated by the “perception gap”between educators and employers, recently documented by theLumina Foundation. According to a study conducted by Gallup forInside Higher Ed, 96 percent of chief academic officers claimed tobe “extremely or somewhat confident” that their institutions areJOBS FOR THE FUTURE1

According to a study conducted by Gallup for Inside HigherEd, 96 percent of chief academic officers claimed to be“extremely or somewhat confident” that their institutions arepreparing students for success in the workforce. In contrast,just 11 percent of employer representatives said they believethat graduates have the skills and competencies needed bytheir businesses.preparing students for success in the workforce. InEducation, remarks, partnerships allow both sidescontrast, just 11 percent of employer representativesto “leverage their combined knowledge of laborsaid they believe that graduates have the skills andmarkets, skills, pedagogy, and students” (Soarescompetencies needed by their businesses (Lumina2010).2014). More effective and long-term engagementof employers is necessary to address these gaps—inperception, but most importantly, in educationaland career preparation.Strong employer engagement is also vital in today’seconomic climate. Slow economic recovery, rapidtransformations in technology, higher-skill andcredential requirements for good-paying jobs,and emerging mismatches between employerW HY EN GAGE E MPLOYE R S?Working with employers is a fact of life forcommunity colleges—particularly their career/technical and workforce divisions. Just asneeds and worker skills make business andeducational partnerships critical. But initiatingsuch relationships and ensuring their success andsustainability is far from simple.employers need postsecondary institutions toprovide a workforce with the right skills andcredentials, community colleges need employers—toget the skills and competencies right, at a minimum;to ensure that curricula are relevant and up-to-date;and to employ graduates. All of these functions areessential, but none are as fundamental as “gettingthe relationship right.” For community colleges,this means working with employers in a variety ofIntegrated pathwaysIntegrated pathways combine basic skills and careertechnical instruction in a single curriculum; offerclear pathways from adult education to communitycollege and postsecondary credentials in high-demandoccupations; and offer comprehensive academic andpersonal support services to increase student success.activities, over an extended period, in a mannermutual interests and leads to mutually successfulEMPLOYER ENGAGEMENT IS CRITICALTO BUILDING SUCCESSFUL PATHWAYSoutcomes.For integrated pathway programs to succeed,that builds trust through participation in projects ofEngaging employers produces benefits at everystage of the educational process, especially in thedevelopment and execution of career pathwayprograms. But the simplest case for it is this:neither employers nor educators can accomplishtheir goals in the labor market alone. As LouisSoares, vice president of the American Council on2A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERSstates and colleges need to identify high-demandindustries and occupations and prepare students forhigh-value credentials in those industries. Doing sorequires close cooperation with industry as well aspublic workforce agencies to ensure that pathwaysand supporting curricula and instruction are closelyaligned with the labor market. States and colleges

in Accelerating Opportunity rely on employers Strategic: approaching employers in the contextwho “actively engage with colleges on pathwayof specific plans, opportunities, and objectives,development,” according to the initiative’s goals,rather than on a spot basis, when the collegeand work toward the goal of consistent exchange ofneeds assistance.labor market information between businesses andcolleges, as well as improved job placement andemployment results for students.DEFINING EMPLOYER ENGAGEMENTEmployer engagement is more than conveningan advisory committee that meets with collegerepresentatives periodically, or a one-off projectof contract training with a single employer,though both of these activities can be valuableto employers, colleges, and students. These Mutually valuable: solving problems andcreating value for both sides of the labormarket—employers (the demand side) andeducation and training providers and learners(the supply side). Wide-ranging: engaging a variety of employersby using varied methods to recruit and involve alarge number, rather than relying on one or a fewof “the usual” representatives. Comprehensive: engaging employers in a varietyactivities are necessary but limiting if the goal isof issues and activities ranging from curriculumdevelopment of curricula, pathways, skill sets, anddevelopment and competency identificationcredentials that align with real labor market needsto student advising and placement, and policyand result in job placement and career successadvocacy on critical issues.for students and employers. To accomplish this,educators need to take a more active approach in Intensive: engaging employers substantivelyand in depth, moving the conversations from arelating to employers.high level (“we need higher-skilled candidates”)Active engagement of employers is differentto an in-depth dialogue about specific skill sets,from a purely advisory approach. In a recentlong-term economic needs, and strengths andpublication, the Corporation for a Skilled Workforceweaknesses of educational programs in meetingdistinguished between a narrowly “advisory” orthem.transactional role for employers and one based on Empowering: encouraging employers to“strategic partnerships” (Parker 2013). Approachingdevelop and assume leadership roles in pathwayemployers as “high-impact,” strategic partnersdevelopment and other initiatives; approachingmeans looking beyond the immediate needs of apotential partners from business at the outset ofprogram or college and seeking ways to make locala process, rather than near the end.employers or industries competitive. It requiresbuilding ongoing opportunities for problem-solvingand program development. Doing so requiresapproaching employers in a listening rather thanan “asking” mode—less “what can you do for us”and more “where is your pain? How can we help inaddressing your challenges?”When employers are engaged as strategic partners, Institutionally varied: engaging employersthrough a number of channels, including industryor professional associations, public workforceentities (Workforce Investment Boards, onestop career centers), chambers of commerce,labor-management training partnerships, andeconomic development authorities, amongothers.their relationship to the community college, orother education and training partners, changes.These qualities distinguish engaged relationshipswith employers from narrowly advisory ones: Continuous: cultivating long-term relationships,A LADDER OF EMPLOYER ENGAGEMENTIt is helpful to understand the college-employerrelationship—and the many activities supportingit—as a continuum of activities and levels ofrather than episodic, one-time, or short-termengagement, with each step or level representingtransactions on an as-needed basis.a higher degree of engagement and deeperJOBS FOR THE FUTURE3

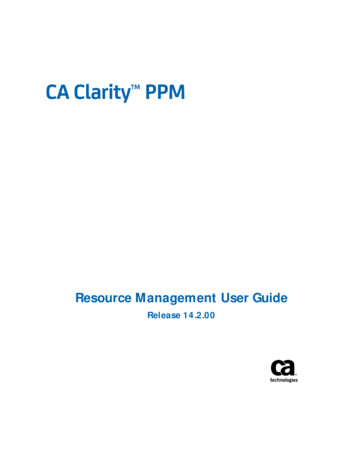

integration of employers in a college’s workforceLevel 4: Convening. Educators work activelyand education activities. Activities taken at oneto recruit and convene businesses and theirlevel, in turn, make more intensive practicesassociations as substantive, ongoing participantspossible at successive levels by demonstrating valuein addressing workforce needs. At a more intensiveand establishing trust and credibility. At higherlevel, colleges serve as hubs or brokers of workforcelevels, employer engagement becomes increasinglycollaboration with employers and other educationcentral to a college or workforce division’s strategy.and training providers.Figure 1 (on page 5) illustrates this continuum andLevel 5: Leading. At the most intensive level,gives examples of activities associated with eachcolleges, employers, and other stakeholders buildlevel of employer engagement. It also shows howpartnerships that transform local or regionalthese activities change as an employer relationshipworkforce systems and enhance the growth ofdeepens from a “new relationship” to a “workingtargeted industries or sectors. Some of the mostrelationship” to a “strategic partnership.”1Level 1: Advising. In the most basic form,effective and long-lasting regional partnerships arethose that are led by industry representatives.employers are consulted informally about hiringThis “ladder” or continuum of employeror training needs through interviews or surveysengagement is not meant to be followed rigidly. Itof businesses in a sector or region. More formally,is a stylized model that illustrates a progressionemployers are represented on advisory boardsfrom less intensive forms of engagement—suchfor a program of study, a grant, or a division.as advisory boards or contract training—to moreWhere advisors are engaged more strategically,intensive ones, such as development of pathwayseducators shift from seeking short-term “input”or partnering for sectoral workforce initiatives.or job placements from employers to collaboratingGiven the needs and interests of educators andwith them to understand workforce challenges andemployers, as well as partnerships or collaborationssupport the success of employers, students, andalready in place, some steps may be skipped,communities.engaged in simultaneously, or performed inLevel 2: Capacity-building. Educators andemployers respond to one another’s needs:colleges provide customized training and skilledjob candidates to individual firms; employers assistwith equipment, space, loaned employees, and otherdifferent sequences. The ladder also suggests howproductive relationships with employers mightevolve, with activities at one level helping buildtrust, momentum, and leverage for more intensiveactivities.supports to the college. Employers lecture or evenThe next section describes each level of employerteach an adjunct course at the college, while collegeengagement in more detail, offering examples andinstructors bring courses to the worksite.lessons from the practice of community collegesLevel 3: Co-designing. The employer shifts frombeing a passive advisor to an active collaboratorand other providers of workforce education andtraining.with the college on education and workforceinitiatives, including design of new curricula andpathways.1The continuum concept of “new,” “working,” and “strategic” relationships with business is adapted from CorporateVoices for Working Families, 2012, Business and Community College Partnerships: A Blueprint.4A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

Figure 1. Ladder of Employer EngagementNew RelationshipKey employerWorking RelationshipStrategic PartnershipLevel ILevel IILevel IIILevel IVLevel dingInitial contact /new relationshipEstablishing trustand credibilityWorkingrelationshipTrusted providerand collaboratorFull strategicpartnerDiscuss hiringneeds, skills,competencies;advise on curricula;contract training;hire graduatesJob site tours;speakers; mockinterviews;internships; needsassessment; loan/donate equipment;recruitingCurriculumand pathwaydevelopment;adjunct faculty ulti-employer/ multi-collegepartnerships WesternTechnicalCollege(WisconsinShifting Gears) BristolCommunityCollege OwensboroCommunityand TechnicalCollege NorTEC Health CareersCollaborativeof GreaterCincinnati /Cincinnati StateCommunityand TechnicalCollegeroleStage ofrelationshipActivityexamplesEngagementexamples bylevel MonroeCommunityCollege AutomotiveTechnicalEducationCollaborative(AMTEC) Columbus StateCommunityCollege(LogisticsART) NorthernVirginiaCommunityCollege(NoVAHealthFORCE) Cabrillo College/ Bay AreaCommunityCollegeConsortium HealthProfessionsPathway (H2P)JOBS FOR THE FUTURE5

LEV EL I : A DV I SI N GAt this initial level of engagement, colleges consult employers abouttheir hiring needs, skills, and competencies required for specificoccupations, and the dynamics of labor supply and demand. Thismay take the form of one-to-one contacts with individual businesses,or regular meetings with an advisory board. By contacting a groupof employers, colleges can obtain an industry-wide perspective andgenerate knowledge that may not emerge from one-to-one contacts,as employers engage and learn from one another. And the informationcomplements labor market intelligence from government or privatesources. Continued conversations with employers help to fine-tune oradapt curricular or pathway designs to current market conditions.Potential questions to pose to employers might include: What contributes to your company’s growth? What policies most affect this industry? What are persistent skill gaps, and why?Using labor market data from government and/or “real time” sourcesaids in deepening understanding of regional and sectoral issues.Presenting findings to employers, to obtain their confirmation orcorrections, helps to anchor and enrich the discussion. Providingdata also signals to employers that educators are prepared for asubstantive discussion, while offering something of value to theemployer.6A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

Other tips for creating an effective advisoryIdeally, employers convened in this fashion becomerelationship with employers:more than occasional advisors to the college. They Solicit information from employers usingcome to see value in joining with other employersa variety of methods, including one-onone interviews, focus groups, surveys, andpresentations. Get out of the office and meetto discuss workforce and educational concerns,extending their network and expanding theirknowledge.employers on their own turf. If holding joint meetings of employers, allowtime for non-workforce topics of interest toparticipants, such as finance, supply chains,or technology.Wisconsin: Shifting Gears initiative’s Regional Industry Skills EducationWhen used as part of a broader strategic approach, advisory boards can generate data essentialto creating industry partnerships, curriculum designs, and programs of study. Wisconsin collegesparticipating in Regional Industry Skills Education, a program of the Shifting Gears initiative, turnedto employers who sit on advisory committees for occupational programs, to identify training needsand align pathway and bridge programs with industry trends. Western Technical College enlistedits manufacturing advisors in such a discussion, resulting in development of a career pathwayin computer numeric control (CNC) machining, as well as the CNC Skills Institute, for training inoperation, set-up, and programming (Chong & Schwartz 2012).Rochester, New York: Monroe Community CollegeRochester’s Monroe Community College used surveys of the region’s employers to assess skill needsand probe for potential gaps. After compiling an extensive database of firms, it conducted twosurveys, including a skill needs assessment. Their research revealed that Rochester’s manufacturers,especially smaller employers, struggled to recruit CNC machinists, particularly those with strongskills in analysis, blueprint reading, and technical writing. Survey results complemented findingsfrom real-time labor market information showing a gap between machinist grads supplied by MCCand openings in the region’s workplaces. As a result, the college mounted an accelerated certificateprogram in precision machining. It is currently planning to continue skill assessment surveys on atwice-yearly basis (Wright 2013).JOBS FOR THE FUTURE7

LEV EL I I : B UI LD I N GE D U CAT I ON A LCA PACI TYAt this stage, engaging employers serves to strengthen collegeprograms and facilitate instruction and skill acquisition. This mightinclude engaging employers to advise on, loan, or even donatetechnology to support hands-on learning. For students who are internsor employees of a college’s business partner, the employer can sharein assessment of project-based assignments, provide placements,and train or mentor students. Some colleges also employ loaned staffor executives as adjunct instructors. Employers, in turn, can hostclassroom-based learning, with college instructors teaching at theworksite, and make accommodations for employee-learners to study,providing release time and financial assistance.With deeper engagement, both sides gain capacity for educationalinnovations such as work-based learning. A good example of suchinnovations comes from Jobs to Careers, a national initiative thatinvested in development of incumbent frontline health care workers asa means to better care. The program, managed by Jobs for the Futureand supported by the Robert Wood Johnson and Hitachi Foundations,included 17 partnerships of health care employers and educationalproviders, including community colleges.8A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

Employers can also expand the capacity of colleges’Other tips for expanding work-based learningcareer and placement services. This can extendopportunities include:from lending guest speakers and conducting mock Work with employers to develop work-basedinterviews to offering shadowing opportunities andhelping assess and screen candidates for careerpathway programs. Of course, the most vital rolefor supporting students’ careers lies in interviewingand hiring students who successfully completelearning opportunities for adult learners(e.g., job shadowing, internships, on-the-jobtraining). Sustain innovative work-based practices bycertificate and degree programs, or employing themencouraging systems changes in both thewhile they study toward a credential. After hiring,community colleges and partner employers,an employer can work with the college, workforcesuch as granting college credit for experientialprovider, or community-based organization tolearning and offering employees tuitioncoach and support the candidate’s retention insupport for basic skills and developmentalemployment and career advancement.courses.Fall River, Massachusetts: Bristol Community CollegeIn one Jobs to Careers site, Bristol Community College, in Fall River, Massachusetts, worked closelywith an addiction treatment facility, Stanley Street Treatment and Resources, to enhance skillsand provide career path opportunities for SSTAR’s frontline counseling and administrative staff.To support a new course on effective group facilitation skills, eight staff members of SSTAR wereappointed as adjunct college faculty. The course was taught both onsite at the facility, by SSTARsupervisors and BCC faculty, and online. Supervisors also provided work-based learning opportunitiesthrough mentoring and coaching of students in the course (Biswas 2011; Quimby & Rogers 2010;Rogers & Wagner 2010).JOBS FOR THE FUTURE9

LEV EL I I I : COD ES I G N IN GCU R R I CULA A N DCA R EE R PAT HWAYSAt the “co-design” stage, educators and employers have conductedsufficient shared activities to demonstrate the value that each canbring to the table, and they have the credibility and trust necessaryfor a working relationship. College staff engage employers indeveloping or modifying curricula in career/technical and professionalprograms. Employers can offer real-time advice and help set standardsfor programs of study, as well as new certificates and degrees thatsupport career advancement. Joint analysis of workforce data andemployer needs informs development of curricula and pathwaystailored to meet these needs. Employers assist in contextualizingcurricula to reflect workplace knowledge and competencies.Establishing strong working relationships between colleges andemployers in the design process offers many advantages. One is thestandardization of curricula, and their translation into credentialswith industry recognition and, in the best cases, transferability acrossemployers (Chong & Schwartz 2012; Bozell & Goldberg 2009). Thiswas demonstrated powerfully in the automotive sector through theAutomotive Technical Education Collaborative (AMTEC), comprisingauto manufacturers and community colleges tasked with definingcompetencies, tasks, and skills needed for specific jobs, identifyingskill gaps, and upgrading curricula and instruction (Parkers et al. 2012;Chong & Schwartz 2012).10A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

The National Network of Sector Partners offers Request authentic workplace materials,these additional recommendations (Mills 2011):scenarios, and examples from employers to Work alongside employers to review and alignassist in contextualizing the instruction.existing curricula or develop new curricula Ask employers to identify the credentialsthat meet national and state standards tothey value for occupations in the chosensupport local job market needs.pathway(s).Owensboro, Kentucky: Owensboro Community and Technical CollegeA close working relationship around curriculum or pathway design helps ensure that graduates’skills are relevant and responsive to employers’ needs—especially critical in today’s rapidly changingenvironment. This sometimes requires going back to the drawing board. Owensboro Communityand Technical College’s manufacturing skills initiative, Meeting Educational Capacity ThroughHigher Education Alternatives, was launched to address the shortage of technically skilled workersin the region’s manufacturing sector. The initiative, with support from the federal Communitybased Job Training grant, was originally designed to serve incumbent workers through on-the-jobtraining, but the Great Recession’s impact reduced employers’ need for this. After consultationwith manufacturers—ones that OCTC had built close relationships with in prior work—the collegeredesigned its program to meet employers’ needs for multiskilled workers whose skills bridged areassuch as welding, electrical, and mechanical, as opposed to specialized employees in each area. Theprogram, available to dislocated workers through online and classroom instruction, offered shortterm, stackable credentials aligned with OCTC’s academic programs. As employers validated theskills and performance of candidates completing the program, they became more comfortable withenlisting the college to train incumbent workers. The latter—lower-level production workers lackingcredentials—were trained to enter pathways and prepare to move up as higher-level workers retiredwith the economy recovering (Milfort et al. 2013).Engage employer partners at the beginning of a designprocess, including discussion of the purpose and goals.JOBS FOR THE FUTURE11

Columbus, Ohio: Columbus State Community College’s LogisticsARTThe LogisticsART program of Columbus State Community College illustrates the value of earlyand ongoing collaboration with employers in curriculum design and implementation. The programoriginated from the needs of Columbus-area logistics firms for both work-ready entry-level workersand higher-skilled incumbents. CSCC worked through area business and sector associations—theChamber of Commerce’s Logistics Council and Ohio’s Skills Bank Logistics Employer Panel—toconvene 16 employers who defined critical skills gaps, and a core group that designed an entry-levelprogram in logistics. Once the larger group vetted the curriculum, the community college deliveredentry-level training in work readiness and the Certified Logistics Program of the Manufacturing SkillsStandard Council. Logistics employers, in turn, conducted the third module of specialized technicaltraining, employing on-the-job instruction on the warehouse floor. According to a U.S. Department ofLabor report, “success in engaging employers has translated into success in placement,” includingcandidates who are formerly incarcerated or who lack high school credentials. The program’ssuccess has induced the Chamber to include LogisticsART in site visits of prospective employers(Workforce3One 2012).12A RESOURCE GUIDE TO ENGAGING EMPLOYERS

LEV EL I V: CON V E N I N GWO R K FOR CEPA R T NE R SHI PSAs employers and educators begin to build sector-focusedpartnerships, they often move to create a bigger “table.” ColumbusState Community College, for instance, through its federal PathwaysOut of Poverty grant, brought business associations as well asindividual employers into its collaboration. The college also engagedthe public workforce system, nonprofit and community-basedservice providers, and economic development authorities (Hay &Blair 2013). Similarly, the Northern Rural Training and EmploymentConsortium (NorTEC), a workforce intermediary serving 11 countiesin rural Northern California, casts a wide net, engaging “economicdevelopment, universities, community colleges, and employer groupsto focus on jobs and business creation.” In so doing, it has made itselfa “regional convener” for this conversation (Workforce3One 2011).In 2005, Northern Virginia Community College convened theregion’s largest health care employers and health professionsschools in response to predicted shortages in the nursing and alliedhealth workforces. The assembled group established a sectoralconsortium, NoVAHealthFORCE, and an action plan to addressworkforce shortages. The consortium’s decision making is steeredby its CEO Roundtable, comprising the executives of six hospital andhealth care systems, and the presidents of the region’s colleges.Meeting twice annually, the group has secured annual allocations byVirginia’s General Assembly in nursing and allied health education,with additional investments by each of the participating employers.JOBS FOR THE FUTURE13

To sustain long-term partnerships with employers, o

This resource guide was made possible with the generous support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. Department of Labor, The Joyce Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, the Arthur Blank Founda