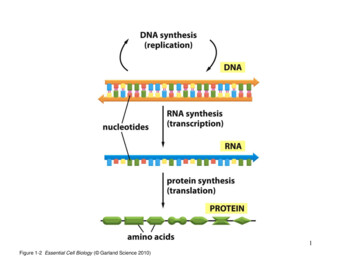

Transcription

THE ESSENTIALConstitution1

THE ESSENTIALConstitutionTable of Contents201020406IntroductionThe Originsof the U.S.ConstitutionThe Genius of theConstitution: TheFounders’ DesignSeparation ofPowers: ThreeBranches ofGovernment10121415How Does theConstitutionalAmendmentProcess Work?Interpreting theConstitutionThe Federalistsand theAnti-FederalistsThreats to theConstitution18212225DebunkingMyths Aboutthe ConstitutionWhy Should theConstitutionMatter to You?Resources toLearn Moreand EndnotesEndorsements

IntroductionWe the People of the United States, inOrder to form a more perfect Union,establish Justice, insure domesticTranquility, provide for the commondefense, promote the general Welfare,and secure the Blessings of Liberty toourselves and our Posterity, do ordainand establish this Constitution for theUnited States of America.The opening words of the preamble to the Constitution, “We the people,” majestically echo themessage of the Declaration of Independence. The preamble is a statement of the hopes of theAmerican revolutionaries as well as their obligations. The Constitution was meant to make possible apolitical society rooted in the rights and freedoms proclaimed in the Declaration. In other words, theConstitution marked not the end of the American Revolution, but rather its fulfillment.The Framers were determined to lay the foundation of the United States on certain principles and toorganize its power in a particular way—so that both freedom and order could be preserved.Understanding the Constitution therefore requires examining each of these principles, and it is essentialthat we do so because, as President James Madison stated in his 1810 State of the Union message toCongress, “a well-informed people alone can be permanently a free people.”1 President Andrew Jacksonmade the same point in his 1837 farewell address: “But you must remember, my fellow-citizens, thateternal vigilance by the people is the price of liberty, and you must pay the price if you wish to securethe blessing.”2This booklet is designed to help all Americans appreciate and defend the meaning and purpose of theConstitution so that they may preserve freedom for themselves and for succeeding generations.401

The Origins ofthe U.S. ConstitutionNo other group of assembled political leadersin history was as attentive to the lessonsof the past as were the men who framed ourConstitution. In designing a charter for the formof government they had in mind, the Framerslooked to both classical and Biblical sources, aswell as to English common law and the EuropeanEnlightenment.The Framers knew a lot about the ancientGreeks, who were the first to devise a politicalsystem in which the people (the demos) heldpower (kratos); they called it demokratia, ordemocracy. The Greek experiment in democracy,however, served mostly as a tragedy to beavoided, not as a model to be imitated.Athens, for example, was the most brilliantand democratic of the Greek city-states butled ancient Greece into its cultural and politicaldecline, dissolving into tribalism and civil war.The Framers therefore rejected the idea of direct,Athenian-style democracy. “Had every Atheniancitizen been a Socrates,” James Madison wrote inThe Federalist Papers, “every Athenian assemblywould still have been a mob.”3The Framers also had a deep knowledge ofthe history of the Roman Republic and thewritings of Cicero, its great defender. The RomanRepublic, which lasted an astonishing 500 years,had a “mixed constitution” in which the chiefmagistrates shared power with the senate andlegislative assemblies. Eventually, however, therule of law gave way to the will of the emperor,and the republic collapsed into tyranny. As Cicerofamously complained: “Our generation, however,after inheriting our political organization like amagnificent picture now fading with age, notonly neglected to restore its original colors butdid not even bother to ensure that it retained itsbasic form ”4With such lessons in mind, the Framers weredetermined to fashion a Constitution that couldweather the storms of faction, jealousy, and thelust for power that had ruined previous attemptsat good government. In 1787, the year theConstitution was drafted, John Adams publishedthe first of three volumes defending the stateconstitutions that already existed.5 He alsoexamined the constitutions of republics such asVenice, where, he wrote, “[g]reat care is taken to balance one court against another and rendertheir powers mutual checks to each other.” Thatsystem broke down when the nobility seized andconsolidated power.As Englishmen, the American colonists alreadyenjoyed a constitutional government that madethem the freest people in the world. The conceptof a balanced constitution was something thatdistinguished Great Britain from the rest ofEurope, and colonial constitutions bore its imprint.It was the British government’s attempt to subvertthese models of self-government that stirredrevolutionary passions.In seeking “a republican remedy for the diseasesmost incident to republican government,”6 theFramers turned to thinkers such as the Frenchphilosopher Montesquieu (1689–1755), author ofThe Spirit of Laws, one of the great works in thehistory of political theory. Montesquieu developeda robust theory of the separation of powers: topreserve individual freedom, the political authoritymust be strictly divided into three separatebut equal branches with legislative, executive,and judicial powers. “When the legislative andexecutive powers are united in the same person, orin the same body of magistrates,” he wrote, “therecan be no liberty.” And as Madison summarized inThe Federalist Papers, “Ambition must be made tocounteract ambition.”7 The Framers elevated theconcept of the separation of powers into “a firstprinciple of free government.”8 They intended theseparation of powers to function as the conceptualcore of a Constitution that would preserve bothorder and freedom.Despite their differences, the architects of theConstitution embraced a common intellectualtradition: wisdom from the classical world of theGreeks and Romans; from the Jewish and Christiantraditions; from the early European Enlightenment;and from more than a century of English politicaldebates about natural rights, political absolutism,republicanism, and religious freedom. Out of thisshared tradition, they produced a Constitutionthat has made possible the greatest advances inhuman liberty and equality in history. As Madisonsummarized their achievement: “The happy Unionof these States is a wonder; their [Constitution]a miracle; their example the hope of Libertythroughout the world.”9Father of the ConstitutionSage of the Constitutional ConventionJames Madison is generally regarded as the Father of the United StatesConstitution. No other delegate was better prepared for the FederalConvention of 1787, and no one contributed more than Madison did toshaping the ideas and contours of the document or to explaining itsmeaning. His contributions included drafting the Bill of Rights.At 81 years old and in declining health, Benjamin Franklin was the oldestdelegate at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. He became known asthe “Sage of the Constitutional Convention,” often acting as a mediator andreminding his fellow delegates that, “we are here to consult, not to contend.”After the final meeting of the Convention on September 17, 1787, Franklinwas approached by the wife of the Philadelphia mayor who asked what thenew government would be. His reply: “A republic, if you can keep it.”0203

FEDERALISMThe Genius ofthe Constitution:The Founders’ DesignThe Constitution’s genius begins withrecognizing both the virtues and limitationsof human nature. It establishes a system ofgovernment that channels human nature towardthe good of all.The first plan the Framers tried after declaringindependence was called the Articles ofConfederation. The government that the Articlescreated failed because it was too weak tocoordinate national policy among states withdifferent priorities. Before the government coulddo almost anything, the Articles required aunanimous vote by all of the states, which oftenput the states in the position of voting againsttheir own individual interests. The Framers sawthat it was not realistic to expect the states todo that. George Washington wrote, “We haveprobably had too good an opinion of humannature in forming our confederation.”10 Sothe Framers tried again, creating a system ofgovernment that did not deny the pursuit of selfinterest, but instead helped to direct it towardcompromise and consensus.04The Framers knew that human nature made this adifficult task. James Madison, for example, wrotethat “[i]f men were angels, no government wouldbe necessary” and that “[i]f angels were to governmen, neither external nor internal controls ongovernment would be necessary.”11 The challengethey faced was that “[y]ou must first enable thegovernment to control the governed; and in thenext place, oblige it to control itself.”12The Constitution accomplishes this bypreventing too much power from ending upin too few hands. The Constitution dividesand disperses government power, making itdifficult for any person or group to obtainpower without first seeking to compromise andreach consensus with others. The Constitutiondivides power to create “checks and balances”13among the three branches of the federalgovernment and between the states and thefederal government while also recognizing thepriority of certain individual rights and requiringwidespread agreement to change the “supremelaw of the land.”The Constitution divides government power indifferent ways. Federalism divides it verticallybetween the state and federal governments.State government is closer to the people andtherefore should be principally responsiblefor looking after the people’s “domesticand personal interests.”14 Especially as thecountry and its population spread, the federalgovernment would be increasingly unable toaddress these ongoing needs.On the other hand, giving states too much powerwould hamper efforts to address the country’scollective interests. For example, if Maine wereinvaded, Florida might consider that the cost ofhelping with resources and lives outweighed thebenefits of preserving the Union. Or if each statehad its own currency, trade and commerce wouldbe almost impossible. The question was how tostrike the right balance between the individualinterests of the states and the collective interestsof the nation as a whole.Always mindful of the need to set limits, theFramers designed the Constitution so thatthe states would give specific powers to thefederal government, not vice versa. The TenthAmendment therefore says that any powers notdirectly given to the federal government “arereserved to the States respectively, or to thepeople.” In other words, the states are assumedto have powers that are not given away, andthe federal government has only the powers itreceives and that are enumerated, or listed, inthe Constitution.SEPARATION OF POWERSIn addition to limiting the powers given to thefederal government, the Framers also dividedthose federal powers into three branches. Thelegislative branch (which itself is divided into theHouse of Representatives and the Senate) makeslaws, the executive branch enforces them, andthe judicial branch interprets them when settlinglegal disputes.An EnduringConstitutionThe U.S. Constitution hasendured for more than twocenturies. It is not onlythe world’s oldest nationalconstitution still in use, butalso the shortest at only4,543 words. Rather thanconcoct a detailed recipecovering every possibleeventuality, the Framers’brilliant design provides astructure and articulatesa set of stable principlesthat provide a timelessguide for good governancethat is enduring and worthpreserving.How does this compareto other nationalconstitutions?Average LifeSpan: 17 Years15America’s Constitution:Over 230 Years05

Separation of Powers:Three Branches of GovernmentChecks and BalancesJUDICIAL BRANCHResponsibilities: Interprets the law. Resolves legal disputes betweenprivate parties, between private parties and the government, and betweendifferent branches of government.JUDICIALChecks the Legislature: Strikes down laws that are unconstitutional.Checks the Executive: Chief Justice presides over Senate impeachmenttrial of the President. Strikes down unconstitutional executive orders orunconstitutional enforcement actions.Strikes Down Laws ThatAre UnconstitutionalAmends Constitution, PassesLegislation Overriding CourtDecisions, Impeaches JudgesLEGISLATIVE BRANCHResponsibilities: Creates federal laws, appropriates money, approvestreaties, and declares war.Checks the Judiciary: Impeaches and removes judges. Adds/removescourts or changes their jurisdiction. Passes legislation that overrides courtdecisions that do not involve constitutional issues. Proposes amendmentsto the Constitution.Checks the Executive: House impeaches the President; Senate decideswhether to remove the President from office. Senate can reject executiveand judicial nominees made by the President or treaties proposed bythe President. Congress can refuse to appropriate funds for presidentialpriorities. House and Senate can override presidential veto of legislation bya two-thirds vote.Strikes DownUnconstitutionalExecutive Orders,Presides overImpeachmentNominatesJudges andJustices, PardonsPeople Convictedby CourtsLEGISLATIVEImpeaches President,Rejects Executive Appointments,Overrides VetoesVetoes Bills,Calls Congress intoSpecial Session,Vice President BreaksSenate TiesEXECUTIVE BRANCHResponsibility: Executes the law.Checks the Legislature: Vetoes bills. Calls Congress into special session.Vice President breaks ties in the Senate.Checks the Judiciary: Nominates federal court judges and Supreme CourtJustices. Pardons or grants clemency to people convicted of federal crimes.06EXECUTIVE07

The GreatCompromiseOne of the most contentiousissues at the ConstitutionalConvention was therepresentation in Congressthat each state would have.Delegates from largerand more populous stateswanted more influence inthe Congress. Delegatesfrom smaller states wantedequal representation. Whatto do? Connecticut delegateRoger Sherman came upwith a brilliant solution: abicameral legislature—twochambers—composed of aHouse of Representativesand a Senate. In the Senate,each state would getequal representation (twoSenators per state); in theHouse, states would be givenproportional representation,based on population.It is quite possible thatwithout this agreement, theConvention would have beenderailed without producing aConstitution that couldbe ratified.08Once again, the Framers wanted to prevent toomuch power from ending up in too few handsbecause that would endanger the freedomsthat government exists to secure. Madison, forexample, wrote that putting legislative, executive,and judicial powers “in the same hands,whether of one, a few, or many may justly bepronounced the very definition of tyranny.”16Quoting Montesquieu, he continued that “therecan be no liberty if the power of judging benot separated from the legislative and executivepowers.” After all, if one body possessed thepower to make and enforce laws, nothing wouldstop it from enacting unjust laws. Likewise, if thesame body exercised both the power to writelaws and the power to decide legal disputes,nothing would stop it from arbitrarily changingthe law to suit the government’s needs. Critically,the government could change the law withoutconsidering the will of the people.THE BILL OF RIGHTSDividing government power vertically throughfederalism and horizontally through the separationof powers is an example of the necessary“internal” control of government that Madisondescribed. The Bill of Rights, which recognizescertain fundamental individual rights, is anexample of an “external” control.Each of us has certain fundamental rights that nogovernment may ever take away. The Declarationof Independence refers to these as “unalienable”rights. These include the freedom to practice anyreligion you choose, to speak your mind, to petitionthe government to change the law, to be free fromunreasonable searches and seizures, to bear arms,to have a fair trial, and to be free from cruel andunusual punishments. The Bill of Rights guaranteesthose rights for each and every individual, even ifthe government or a majority of the people mightwish to deny those rights to someone.Separating the powers of government to protectagainst tyranny makes sense, but why doesthe Constitution separate them as it does? It allcomes down to timing. A large body of peoplelike Congress acts slowly and deliberately. Whenit comes to passing laws that will govern all thepeople of the country, deliberation and debatehelp to promote compromise and consensus. Butspeed is necessary if the nation is attacked anda defense must be mounted. In that case, onePresident can act much faster than an assemblycan. Likewise, when the nation needs to speakto foreign countries, one person can present aunified message that Congress cannot.Justice Antonin Scalia once observed that“[e]very banana republic in the world has a bill ofrights.” Most are just “words on paper” becausethose countries’ constitutions do not “preventthe centralization of power in one person or inone party.”18 It is the structure of governmentestablished by our Constitution that makes oursystem distinctive. Federalism and the separationof powers, a bicameral legislature, and a judiciarythat is independent of the two political branchescombine to form a design for government thatmakes the Bill of Rights real and meaningful.The Constitution gives to the judicial branch thepower to interpret and apply the Constitutionor statutes to decide individual legal disputes.Alexander Hamilton explained that this requiresthe “judgment” of a court rather than the “will”of the legislative branch or the “force” of theexecutive branch.17 Unlike legislators or thePresident, federal judges do not have specificterms, so they are free to render judgmentimpartially and without fear of political retaliation.The U.S. Constitution is the oldest written charterin continuous use anywhere in the world. In thefamous case of Marbury v. Madison, the SupremeCourt in 1803 explained that the Framers wrotethe Constitution down for a very practical reason:so that its rules for government “may not bemistaken, or forgotten.”19 When he left office,President George Washington said that becausethe Constitution expresses the people’s will, it is“sacredly obligatory upon all” until it is changedAMENDING THE CONSTITUTIONby “an explicit and authentic act of the wholePeople.”20 That act is the process for amending theConstitution.By permitting amendments, the Constitutionallows the people of today both to continueoperating with the rules that have beenestablished and to change those rules if theysee fit to do so. By design, amending our “greatcharter of liberty” is difficult and requiresextensive deliberation to ensure that amendmentsreflect the settled opinion and will of the people.As James Madison explained in The Federalist,the amendment procedure allows subsequentgenerations to correct errors and make whatever“useful alterations will be suggested byexperience.”21 At the same time, the difficulty ofthe amendment process prevents the Constitutionfrom being weakened or deprived “of thatveneration, which time bestows on everything, andwithout which the wisest and freest governmentswould not possess the requisite stability.”22Amendments have been suggested thousands oftimes since the Constitution was ratified in 1789,but the states have approved only 27 of the 33amendments Congress has actually proposed.These included adding the Bill of Rights, changingthe way the President and Vice President areelected, abolishing slavery, preventing stategovernments from discriminating against anyperson, guaranteeing the right to vote to allcitizens regardless of race or sex, giving the federalgovernment the power to collect an income tax,providing for the direct election of Senators, andboth outlawing (in 1919) and then legalizing (in1933) the production and distribution of alcohol.The great genius of the Constitution is this: itpermits the people to govern themselves byputting the power of government in their hands,by protecting them from those who would takepower or liberty from them, and by giving eachsuccessive generation the ability to improve uponthe government bequeathed to them by thosewho came before.09

How Does the ConstitutionalAmendment Process Work?STEP 1 : AMENDMENT IS PROPOSEDThis can happen one of two ways.Did You Know?1. None of the 27 amendments to the Constitution havebeen proposed by a Convention of States.2. Congress controls the mode of ratification for eachproposed amendment.3. Twenty-six amendments were ratified by threefourths of state legislatures. One amendment—the 21stAmendment, which repealed Prohibition—was approvedby three-fourths of state conventions in 1933.OPTION 2OPTION 1Proposed by Congress with atwo-thirds majority vote in boththe House of Representativesand the Senate.Proposed by “a convention forproposing amendments” (commonlyreferred to as a “Convention ofStates”), which is called by Congresson the application of two-thirds of thestate legislatures (at least 34 states).STEP 2 : RATIFICATIONThere are two ways that an amendment can be ratified.104. Amendments to the Constitution can be repealed byadding another amendment.OPTION 1OPTION 2Legislatures in three-fourthsof the states (at least 38 states)approve the amendment.Ratifying conventions in three-fourthsof the states (at least 38 states) approvethe amendment.What Is a StateRatifying Convention?The Framers inserted a method of ratification into theConstitution that would allow the amendment processto bypass state legislatures. A ratifying convention is anentirely separate body from the state legislature, madeup of delegates. This would presumably include averagecitizens, who are less likely to bow to political pressure.The guidelines and laws for conducting these ratifyingconventions vary from state to state.11

Interpreting the ConstitutionThe Constitution is the American people’srulebook for government and thereforemust be actively applied and defended toensure that government does not get out ofcontrol. Many people probably think that onlylawyers can understand the Constitution, butthat’s not true. The Framers wanted people toread and understand the Constitution. The textof the Constitution was widely read andvigorously debated by just about everybodyin this country at the time it was proposedand sent to the states for ratification. Readingand understanding the Constitution is just asimportant today as it was then.Three guidelines show the proper method forinterpreting the Constitution. The first guidelineis that the Constitution is a written document. Inthat sense, it is like a note to a friend, a contractto buy a car, a college exam, or a grocery list.Every time we handle something written bysomeone else, we first read the words and thentry to figure out what the author meant by whatthe author wrote. This basic method appliesThey did this in two stages. The first occurredbetween May 25 and September 17, 1787, whenstates sent delegates to Philadelphia to writeit. Second, each state held a convention todecide whether to ratify, or approve, the draftConstitution. Those ratifying states were theauthority that made the Constitution the “supremelaw of the land.” Amendments that become part ofthe Constitution go through the same two stages:proposal and ratification.The third guideline concerns how to know what“we the people” meant by the words of theConstitution. The most important thing is tokeep the goal of interpretation always in mind:determining what the author meant by whatthe author wrote. Interpreting the Constitutiontherefore requires figuring out what the peoplewho established or amended it meant by thewords they put in it.This interpretive approach is sometimescalled originalism because it focuses on theConstitution’s original meaning as determined“Any defensible theory of constitutional interpretation mustdemonstrate that it has the capacity to control judges.”—ROBERT BORKwhen courts interpret laws enacted by Congressor state legislatures. Statutory construction is“the process of determining what a particular lawmeans so that a court may apply it accurately.”23The second guideline is more specific. Back in1795, the Supreme Court said that the Constitution“can be revoked or altered only by the authoritythat made it.”24 What is that authority? TheConstitution’s first three words provide theanswer: “We the people,” it says, “do ordain andestablish this Constitution.”12by “the authority that made it.” This job can bechallenging for several reasons. The main bodyof the Constitution and most of its amendments,for example, were ratified a long time ago.Constitutional language can sometimes beunfamiliar or awkward to the modern reader.The Constitution’s provisions have come tous not from a single person, but from groupssuch as the Framers or, in the case of theamendments, Congress. It may be difficultto settle on what the people understood orintended the Constitution to mean at the timeeach provision was ratified, but theirs is theonly meaning that counts.The main reason for using any approachother than originalism is simply to make theConstitution mean something other than whatits authors intended. Since the 1930s, somelegal scholars, judges, and even Presidentswho want the Constitution to mean somethingelse have suggested criteria or standards otherthan originalism. President Franklin Roosevelt,for example, said in 1937 that the Constitutionshould be interpreted “in the light of presentday civilization.”25 Others have suggested usingsuch vague standards as “distinctive publicmorality”26 or the “well-being of our society.”27While originalism is focused on finding theConstitution’s meaning in an identifiablesource that is independent of judges, thesealternate standards originate solely from judges’preferences, allowing judges to reach any resultthat they desire.Imagine the chaos if the Constitution’s rulesthat limit government power meant whateverthe government wanted them to mean. Nobodywould or should feel safe if that were the case.While the Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madisonsaid the Framers wrote the Constitution downso that its rules for government “may not bemistaken, or forgotten,” any approach other thanoriginalism would treat those rules as if they hadbeen written in disappearing ink.Robert Bork had the better view whenhe wrote that “any defensible theory ofconstitutional interpretation must demonstratethat it has the capacity to control judges.”28Originalism—seeking to determine theConstitution’s original meaning—does thatbecause it is rooted in the principle that theConstitution’s meaning comes from “theauthority that made it.” Until the peoplechange it through the amendment process,the Constitution says what its authors said andmeans what its authors meant.A Model forOther NationsThe idea of a writtenconstitution based on thesovereignty of the people,enshrining fundamentalprinciples like limitedgovernment, separation ofpowers, checks and balances,and judicial review, wasexceptional and an entirelyAmerican innovation. Theseprinciples have influencedand inspired freedomloving people all over theglobe. Beginning in 1791with Poland and France andexpanding through the yearsto include numerous othercountries, including Germany,Switzerland, Australia, Canada,Yugoslavia, Hungary, and thePhilippines, among others,these countries importedAmerican constitutionalprinciples into their owngoverning documents. Whilenot all have experiencedsuccessful results, peopleof nearly every nation nowunderstand the value of awritten constitution andthey often use the Americanexperience as a template. Acredible case can be made thatour most valuable export hasbeen our Constitution.2913

Threats to the ConstitutionBecause the people use the Constitution toremain the masters of government, the mostserious threats to the Constitution are the onesthat allow government to ignore rather than followit. These threats can come from each of the threebranches of government.The Federalists andthe Anti-FederalistsBefore the Constitution was ratified, prominent statesmen publicly debated the merits and flaws ofthe newly proposed government through a series of essays that were published under pseudonymsin newspapers and pamphlets across the country. The two sides debating the issue became known asthe Federalists, who favored ratification, and the Anti-Federalists, who opposed ratification.FEDERALISTSUnder the pen name Publius, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, published 85 essays invarious New York State newspapers from 1787–1788, countering the arguments of the Anti-Federalistsand advocating ratification. Their essays touted the virtues of the Constitution, including a defense ofa strong permanent national union, the need for an energetic government that could tax and providefor the national defense, and the value of the proposed republican government, describing its branchesand powers. Thomas Jefferson later claimed that these essays, collectively known as The FederalistPapers, were “the best commentary on the principles of government which ever was written.”THE “LIVING CONSTITUTION”AND JUDICIAL ACTIVISMRecall that the Constitution is the meaning of itswords. Judges cannot change the Constitution’swords, but they threaten the Constitution justas much by changing what those words mean.Rather than seeking to understand what theConstitution’s authors meant, some activist judges,under the guise of interpretation, substitute whatthey want the Constitution to mean as if theywere creating a different Constitution in theirown image. These judges and those scholars whosupport them are s

message of the Declaration of Independence. The preamble is a statement of the hopes of the . Order to form a more perfe