Transcription

A LANDOWNER’S GUIDE FORWILD PIG MANAGEMENTPRACTICAL METHODS FOR WILD PIG CONTROLBill Hamrick, Mark Smith, Chris Jaworowski, & Bronson StricklandMississippi State University Extension Service &Alabama Cooperative Extension System

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe thank USDA/National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Renewable Resources Extension Act(RREA), the Alabama Wildlife Federation, Mississippi State University, Auburn University, AlabamaDepartment of Conservation and Natural Resources, and Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries,and Parks for their financial and moral support of this publication. The authors also acknowledgewith gratitude the contributions of Scott Alls, Carl Betsill, Jay Cumbee, Kris Godwin, Parker Hall,and Dana Johnson, USDA/APHIS-Wildlife Services; Billy Higginbotham, Texas AgriLife ExtensionService; Sherman “Skip” Jack, Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine; Joe Corn,Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study; Ricky Flynt and Brad Young, Mississippi Departmentof Wildlife, Fisheries, & Parks; Ben West, University of Tennessee Extension Service; and Jack Mayer,Savannah River National Laboratory.The mention of commercial products in this publication is for the reader’s convenience and is not intendedas an endorsement of those products nor discrimination against similar products not mentioned.To obtain additional copies of this publication, please visit res.com/pubs, or http://www.aces.edu/pubs, where an electronic copy can be downloaded atno charge.Printed copies may also be ordered through Mississippi State University Extension Service and AlabamaCooperative Extension System. Mississippi State University Extension Service: Contact your county Extension office. Alabama Cooperative Extension System: Call (334) 844-1592 or e-mail publications@aces.eduPublished byMississippi State University Extension Service andAlabama Cooperative Extension System, Alabama A&M University and Auburn UniversitySeveral cover photos provided by Chris Jaworowski, Dee Mincey, Randy DeYoung, Ronald Britnell, & Bill Hamrick.

CONTENTSIntroduction1Range Expansion2Damage6Agricultural Damage.7Forest Damage.7Threats to Native Wildlife.8Environmental Damage.8Learn to Recognize the Signs.9Wild Pigs and Disease12Disease Prevention.12Management14Trapping Wild Pigs. 14Scouting the Trap Location.15Conditioning Pigs to the Trap. 16Baiting and Setting the Trap.18Types of Pig Traps.18Box Traps.18Cage Traps.19Corral Traps.20What Is the Appropriate Size for a Corral Trap? . 20Building a Circular Corral Trap . 20Trap Door Designs.22Single-Catch Trap Doors.22Multicatch Trap Doors.22Trigger Mechanisms.25The Root Stick.25The Trip Wire.26High-Tech Pig Trapping .27Five Steps for Systematic Wild Pig Removal.29Snaring Wild Pigs.30Euthanizing Wild Pigs.30

Shooting and Hunting Wild Pigs.30Nontarget Species.32Is “All-Out War” on Wild Pigs a Good Idea?.34Where Do We Go From Here?35Appendix I: Zoonotic Diseases36Appendix II: The Corral Trap37Appendix III: Trap Door Designs38Appendix IV: Trigger Mechanisms43Appendix V: Monitoring Pig Traps and Strategic Baiting48Glossary51Additional Resources53Authors54Guest ArticlesDisease Impacts of Wild Pigs.13Using Remote-Sensing Cameras to Enhance Wild Pig Trapping Efficiency.17Decoying Wild Pigs.24Trip Wires Versus Root Sticks.26Nighttime Options for Wild Pig Control.31Hunting Pigs with Dogs.33

1INTRODUCTIONWild pigs are not native to the Americas. They werefirst introduced to the United States in the 1500sby the Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto, whotraveled extensively throughout the Southeast.Because pigs are highly adaptable and capableof fending for themselves, they were a popularlivestock species for early explorers and settlers. Inthe centuries following European exploration andcolonization of the eastern United States, settlers,farmers, and some Native Americans continuedto promote the spread of pigs by using free-rangeWild pigs arenot native to theAmericas.livestock management practices. In the early 1900s,Eurasian or Russian wild boar were introducedinto portions of the United States for huntingpurposes. As a result of cross-breeding with wilddomestic stock, many hybrid populations now existthroughout the wild pig’s range.Alabama DCNR, Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division, Chris JaworowskiWild pig is a collective term used to refer to feral domestic pigs (left), Eurasian wild boar (right), and hybrids resultingfrom interbreeding of the two. As a result of interbreeding and their diverse background, wild pigs come in a variety ofcolors and sizes.

2RANGE EXPANSIONToday, wild pigs are both numerous andwidespread throughout much of the UnitedStates, with established populations in at least36 states and an additional 12 states reporting apresence of wild pigs. Historically, problems withwild pigs were limited mostly to the southeasternstates, California, Hawaii, and Texas. However, inthe last 20 years, wild pig ranges have expandeddramatically to include much of the United States,and populations now exist in such northerlyclimates as Michigan, North Dakota, and theprovinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan inCanada. This current distribution of wild pigs,almost nationwide in scope, is not a consequenceof natural events. Instead, it has resulted largelyfrom translocation of wild pigs by humans andfrom “the nature of the beast.”THE HUMAN FACTORThe popularity of wild pigs as a game species hasplayed a major role in the expansion of their rangethroughout the United States. In some cases, thesudden presence of wild pigs in an area wherethey previously did not exist can be attributed toescapes of stocked animals from privately owned,“game-proof” fenced hunting preserves. In othercases, the sudden presence of wild pigs is a resultof illegal translocation: the practice of capturingwild pigs, transporting them to new locations, andreleasing them into the wild.One group that continues to fuel this practiceconsists of irresponsible and uninformed pighunting enthusiasts whose goal is to establishlocal wild pig populations for recreational hunting.A second group comprises those whose goal isto profit from the capture and sale of wild pigs toWild pigs are bothnumerous andwidespread throughoutNorth America, withestablished populationsin at least 36 states.hunting enthusiasts. Wild pigs are quick to learn,and those that have been previously captured,transported to a new location, and released oftenare a daunting challenge to recapture. As a result,these actions contribute to the spread of thisnonnative, highly invasive species.THE NATURE OF THE BEAST:BIOLOGICAL AND BEHAVIORAL TRAITSPigs possess many biological and behavioral traitsthat enable them to live just about anywhere andquickly populate new areas.1. Wild pigs are habitat generalists, meaningthat they are highly adaptable and can livein many different habitat types throughouta landscape or region. They can tolerate awide range of climates, ranging from thehot, dry deserts of Mexico to the subzerotemperatures of the extreme northernUnited States and Canada.2. Wild pigs are opportunistic omnivores. They eat mostly plant matter andinvertebrate animals such as worms,insects, and insect larvae. When the opportunity presents itself,wild pigs will eat small mammals, theyoung of larger mammals, and the eggsand young of ground-nesting birds andreptiles.

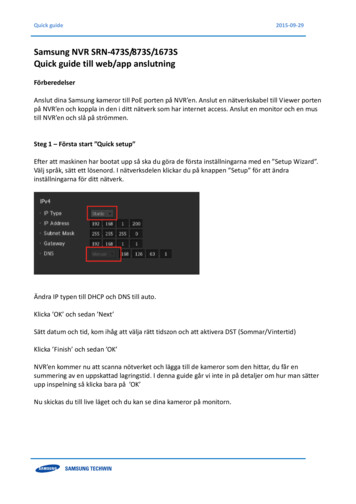

31988 DistributionAdapted from Feral/Wild Swine Populations, SCWDS1988200920131988 to 20092009 to 2013118% rate of land area increasefor the conterminous United States.34% rate of land area expansionfor the conterminous United States.That is a 5% annual increase.That is an 8% annual increase.Wild pigs are numerous and widespread across the United States; shaded areas on the map represent established breedingpopulations. Notice the progression northward and the small, isolated populations in the far northern states, many milesfrom previously established populations.

4Wild pigs are habitat generalists, meaning that they are highly adaptable and can live in manydifferent habitat types throughout a landscape or region.USDA/APHIS/Wildlife Services, Dan McMurtry and Chris JaworowskiUSDA/APHIS/Wildlife Services, Dana JohnsonMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickTexas A & M University-Kingsville, Randy DeYoungGiven food, water, and cover, wild pigs can live almost anywhere. Clockwise from top left: bottomland hardwood swamps,coastal marshes and barrier islands of the southeastern U.S., prairie and mixed forest provinces of the northern U.S. andsouthern Canada, and desert regions of the southwestern U.S. and Mexico.

53. Wild pigs have a high reproductive potential. Some individuals reach sexual maturityas early as 6 months of age. Litter sizes average about six pigletsbut range from three to eight piglets. Females can farrow twice per year.4. Wild pigs have low natural mortality. They are most vulnerable to predationwhen they are young. Once pigs reachabout 40 pounds, few predators pose aserious threat. Although diseases and parasites havesome effect on wild pig populations,their impacts are not well knownand the factors involved are poorlyunderstood. The highest rates of wild pig mortalityare a result of human activities:hunting, trapping, and automobilecollisions.SCWDS, Jay CumbeeThe expansion of wild pig ranges across the U.S. duringthe last 20 years is mostly a result of human activities,such as illegal translocation of wild pigs and escapes fromfenced hunting preserves that offer wild boar hunts.What Do Wild Pigs Eat?% ofDiet% ofDiet1009080706050403020100Plant MatterAnimal MatterMast(hardandso;),roots,plantma er,agriculturalcropsRep les,amphibians,newbornofground- ‐nes ngbirdsandmammals,fawns,invertebratesSchley, L. & Roper, T. J. (2003) Diet of Wild Boar Sus scrofa in Western Europe, with particular reference toconsumption of agricultural crops. Mammal Review 33: 43-56.Wild pigs are opportunistic omnivores. This graph shows how wild pigs can negatively impact vegetation and local fauna.

6DAMAGEToday, wild pigs area problem for manylandowners andagricultural producers.Damage from pigs is nothing new, and whereverwild pigs are present, they inevitably becomea problem. Although pigs were an importantfood source for early Americans, they alsowere widely considered a nuisance. Free-rangelivestock practices were commonplace in colonialAmerica, and roaming pigs routinely damagedcrops and food stores of both colonists andNative Americans. Thus they were a source ofmuch tension among colonists and even more sobetween colonists and Native Americans.Today, free-range livestock practices are nolonger used in the eastern United States, and allfree-ranging pigs are considered wild pigs. Justlike the free-ranging domestic pigs of early America,today’s wild pigs are a problem for many landownersand agricultural producers. In addition to damagingcrops and livestock, wild pigs damage forests and area threat to native wildlife and the environment. Aconservative estimate of the cost of wild pig damageand control practices in the United States foragriculture alone is 1.5 billion annually.Alabama DCNR, Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division, Chris JaworowskiArkansas Game and Fish Commission, Rachel SpauldingUSDA/APHIS/Wildlife Services, Dan McMurtry and Chris Jaworowski

7SCWDS, Jay CumbeeSCWDS, Jay Cumbee and Bill HamrickBecause of the diseases they carry, wild pigs pose a real threat to commercial swine operations. Above left: a well-worn wildpig trail leading from a nearby swamp to the feed bins of a commercial swine operation. Above right: a wild pig harvestedat night beneath the feed bins of the same commercial swine facility.AGRICULTURAL DAMAGE. Wild pigs consume and trample crops,and their rooting and wallowing behaviorsfurther damage crop fields. Rooting andwallowing create holes and ruts that, ifunnoticed, can damage farm equipment andpose a hazard to equipment operators. Wild pigs may at times prey on livestock,including newborn lambs, goats, and calves.Livestock predation usually occurs oncalving or lambing grounds where wild pigsmay be attracted by afterbirth and fetaltissue.FOREST DAMAGE. Hardwood mast (for example, acorns andhickory nuts) is a major food source for wildpigs. Consequently, regenerating hardwoodsfrom seed can be difficult in areas with highwild pig populations. In areas where mastor fruit has already germinated, rootingEddie ParhamPig rubbing and scent marking behavior damages treesand leaves them vulnerable to disease and parasites.

8Mississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickPigs are attracted to longleaf pine seedlings because theroot systems are high in carbohydrates. Pigs chew the rootsto extract the sap and spit out the masticated remains.Wild pigs are fierce competitors with native wildlifespecies for food resources such as hard mast.activities often dislodge and damage youngseedlings. Wild pigs can damage pine plantations andnatural regeneration areas through directconsumption, rooting, and trampling.Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) seedlingsin particular are favored by wild pigsbecause the soft root systems are high incarbohydrates. Wild pigs can damage both pine andhardwood trees by using them as scratchingposts. Intense rubbing and damage to thebark layers can leave trees more vulnerableto harmful insects and pathogens (bacteria,fungi, and viruses).THREATS TO NATIVE WILDLIFE. Wild pigs compete for food and space withnative wildlife species, especially gameanimals such as deer, turkey, and quail. Wild pigs can be significant predators ofeggs and newly hatched young of ground-nesting birds and sea turtles, small mammals,salamanders, frogs, crabs, mussels, andsnakes. Though not considered a significantpredator of white-tailed deer fawns, wildpigs do sometimes kill and eat newborns. Wild pig rooting, wallowing, and tramplingdamage native plant communities that providehabitat and food sources for native wildlifespecies.ENVIRONMENTAL DAMAGE. Rooting, wallowing, and trampling activitiescompact soils, which in turn disrupts waterinfiltration and nutrient cycling. Also, thesesoil disturbances contribute to the spread ofinvasive plant species, which typically favordisturbed areas and colonize them morequickly than many native plants. Wild pig activity in streams reduces waterquality by increasing turbidity (excessivesilt and particle suspension) and bacterialcontamination. In time, turbidity and added

9Westervelt Ecological Services, John McGuireEddie ParhamWild pigs threaten ecologically sensitive communities suchas the pine flatwoods of the Lower Coastal Plain of thesoutheastern U.S.Wild pig activities in streams and other waterways cangreatly diminish water quality.contaminants affect a variety of nativeaquatic life, most notably fish, freshwatermussels, amphibians, and insect larvae. Insome streams, feces from wild pigs haveincreased fecal coliform concentrations tolevels exceeding human health standards. Destruction of vegetation in freshwaterand brackish marshes not only reducesaquatic life and water quality but also affectsecosystem services, such as water filtration,flood control, and storm surge protection.LEARN TO RECOGNIZE THE SIGNSSometimes landowners do not realize they havepigs on their property until they actually see apig or until the damage is widespread. The earlierthe presence of wild pigs is detected and controlmeasures begun, the better. Some telltale signsthat wild pigs have moved into an area includetracks, rooting, wallows, nests or beds, and treeand post rubs.Mississippi Levee BoardPig rooting along levees, roadsides, and otherthoroughfares can lead to costly infrastructure repair,equipment damage, and public safety concerns.

10Wild pigs leave field signs that are unique and identifiable, making it relatively easy to determinewhether wild pigs inhabit an area.Mississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickRootingWallowMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickWallow and tree rubUtility pole rub

11Mississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickWild pig nestWild pig trackMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickMississippi State University Extension Service, Bill HamrickWild piglet trackDeer track

12WILD PIGS AND DISEASEWild pigs are known carriers of at least 45 differentparasites (external and internal) and diseases(bacterial and viral) that pose a threat to livestock,pets, wildlife, and in some cases, human health.The risk of being infected by one of these diseasesis real: in 2007, Florida health officials documentedthat 8 of 10 human cases of swine brucellosis werelinked to wild pig hunting activities. Many of thesediseases are transmitted through contact with bodilyfluids and handling or ingestion of infected tissues.Diseases can also be transmitted indirectly throughticks or contaminated water sources. For moreinformation on wild pig diseases, see page 31.Wild pigs are knowncarriers of at least 45different parasites anddiseases.DISEASE PREVENTIONFollow these simple measures to avoid infectionwhen handling or field dressing wild pigs:Wear latex or nitrile gloves; pathogens can enterthe body through cuts on hands or torn cuticles.Avoid splashing body fluids into your eyes ormouth.Follow correct refrigeration, freezing, andcooking methods. Freezing to 0 F will renderbacteria inactive but will not destroy them;once thawed, bacteria can again becomeactive. You should not rely on home freezingto destroy Trichina and other parasites.Thorough cooking will destroy all parasites.Cook meat until internal juices run clear oruntil it has reached an internal temperatureof 170 F.Wash your hands thoroughly after fielddressing and processing meat, even if youwear gloves.USDA-Wildlife Serv ices, Cal BetsillWearing latex or nitrile gloves will reduce your chances ofpotential disease risks associated with handling wild pigs.clean and disinfect work areas Thoroughlyand tools used to dress and butcher wild pigs.of animal remains, used gloves, and Disposeother materials properly. Animal remainsshould not be left for scavengers, nor shouldthey be fed to dogs. Depending upon yourjurisdiction, several methods of appropriatedisposal may be considered. Check withyour local health department or state wildlifeagency.

13Sherman “Skip” JackProfessor of VeterinaryPathologyMississippi StateUniversity College ofVeterinary MedicineDISEASE IMPACTS OF WILD PIGSDiseases of wild pigs affect humans and otheranimals in several ways. First, there are diseasesthat are transmissible to humans, called zoonoticdiseases. Then there are diseases that might impactlivestock and pets (for example, swine, cattle,and dogs). A third group of diseases are foreignanimal diseases (FADs), those that have neverbeen present in North America or those thatwere present at one time but have been eradicatedduring the last 100 years. (Examples are foot-andmouth disease and hog cholera, or classical swinefever.) While not a direct threat to human health,FADs would have overwhelming economic impactif introduced—or reintroduced—and perhapsnever again could be eradicated from our continentbecause of the continued expansion of wild pigranges.Foreign Animal Diseases & PseudorabiesForeign animal diseases include a number ofconditions that have never been identified in NorthAmerica or have been eradicated during the pastcentury. Some of these diseases affect only swine(for example, hog cholera, or classical swine fever,and African swine fever), but others affect multiplespecies such as foot-and-mouth disease, which canaffect cloven-hooved animals like cattle, deer, andelk. Both hog cholera and foot-and-mouth diseasewere eradicated from the United States duringthe previous century (hog cholera during the1970s, foot-and-mouth disease in the early 1900s).However, eradication occurred before wild pigswere found in most of the lower 48 states, and eventhen the cost was in the billions of dollars. Thus,reintroduction of those diseases today would havea greater host population in which to spread andwould be much more costly, if not impossible, toeradicate again.Pseudorabies virus (PRV), while not foreign,is another disease with implications for nonswineanimals such as cattle, sheep, and dogs. This diseaseis a herpes virus and is not related to rabies. Somesymptoms of the disease may resemble rabies, thusthe term pseudorabies. It sometimes kills pigs butis routinely fatal in nonswine species that becomeinfected either through direct contact or ingestionof tissues from PRV-positive wild pigs. Pseudorabiesis a reportable disease and may restrict transportinganimals (even uninfected ones) across state lines.Thus the economic impact may extend well beyondaffected animals or affected premises. See page 31for more information on common diseases amongwild pigs.Bacteria (Staphylococcus)Virus (Swine influenza)Wild pigs are known carriers of bacterial and viraldiseases that are a threat to livestock, wildlife, pets,and, in some cases, human health.

14MANAGEMENTWild pig populations can be managed by lethal ornonlethal methods. Nonlethal methods includeinstalling fencing to exclude pigs, using guardanimals to protect livestock, and vaccinatinganimals to prevent disease spread. Although insome situations nonlethal methods are appropriateand effective, in many cases they are not a goodoption, either because they do not work well orare too expensive. Therefore, lethal methods areoften the most practical and widely used. Theyinclude trapping, shooting, and hunting withdogs. Currently, there are no toxicants registeredfor use on wild pigs in the United States, sopoisoning is not an option.Hunting and trapping regulations vary bystate. Be sure to check the hunting and trappingregulations specific to your area or contact yourlocal conservation officer before beginning anywild pig trapping and removal program in an area.TRAPPING WILD PIGSTrapping is the most efficient means for removingwild pigs because it is a continuous activityrequiring far less time and effort than othermethods such as hunting. Successful pig trappinghinges upon several key components:locating high-use areas for potential trap sitesand attracting pigs to these locationsconditioning pigs to the trap enclosureeffective trap design and sizepatience Currently, there are notoxicants registered foruse on wild pigs in theUnited States.Alabama DCNR, Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division, Chris JaworowskiWild pigs do notacknowledge boundariesand land lines. Therefore, acooperative trapping effortwith adjoining landownerswill prove more successfulthan conducting a trappingprogram on your own.

15Scouting the Trap LocationOnce you discover wild pigs have moved ontoyour property, do not immediately build a trap andset it to catch. Instead, first scout the propertyand identify their travel routes and any other areasof recent activity—bedding and loafing areas, mudwallows—and establish nearby bait sites to attractpigs from the surrounding area. Depending on thesize of your property and the distance betweenareas with recent pig activity, you may want toestablish several of these bait sites. A good rule ofthumb is to establish a bait site every 100 to 200acres across a property. Here are several factorsto consider when choosing a bait site:Level ground with enough open to semiopen area to allow for building a four- tosix-panel corral trap if pigs should beginusing the site.Shade (full or partial); during warmmonths, a captured pig in the shade isless stressed and less likely to heavilydamage a trap trying to escape.Vehicle access close to the site saves timeand labor in constructing, baiting, andchecking the trap, and also in removing pigcarcasses from the trap. It is usually best to begin baiting wild pigswith whole-kernel dried, shelled corn. It is readilyavailable at local feed and seed stores, is easy towork with (there is no excessive odor or messas with fermented corn), and, more often thannot, it does a good job of attracting wild pigs. Ifit becomes clear that pigs are visiting your baitsite but not readily consuming the dry corn,experiment with fermented corn or other types ofbait and/or attractants.There are several different methods you canuse to bait your scouting sites. The simplest ofthese is to scatter 1-2 gallons of corn on theground in an area 8-10 feet in diameter. Whilethis is a “tried and true” method for baiting wildpigs, there are a couple of downsides: (1) Baiton the ground for longer periods of time is moresusceptible to becoming toxic (aflatoxins) and/or being consumed by nontarget species such asdeer, turkey, and raccoons; and (2) You have tocheck the sites daily in case the corn needs to bereplenished.The “bait bucket” is another method that issometimes used for baiting wild pigs. A bait bucketis simply a 5-gallon plastic bucket half filled withcorn and covered in water and tied or strapped tothe base of a tree. While this method will greatlyreduce the amount of bait consumed by nontargetspecies, you either need access to a nearby watersource or you will have to transport water to thesite. Bait buckets can be checked every few daysto determine if pigs are using them.The most convenient method for baiting wildpigs is to set up an automatic spin-cast feederat each site, programmed to dispense corn at aregular time each day. In doing so, you can reduceyour site visits

Schley, L. & Roper, T. J. (2003) Diet of Wild Boar Sus scrofa in Western Europe, with particular reference to co