Transcription

Sickle Cell DiseaseAwareness and EducationStrategy DevelopmentWorkshop ReportChapter Name1

Sickle Cell DiseaseAwareness and EducationStrategy DevelopmentWorkshop ReportPublication No. 56-205NAdministrative Use OnlyApril 2010

AcknowledgmentsThe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) would like to thank all workshopparticipants, speakers, panelists and moderators, as well as workgroup facilitators and reportersfor contributing their expertise, ideas, and experiences with sickle cell disease prevalence, management,and education to the NHLBI Sickle Cell Disease Awareness and Education Strategy DevelopmentWorkshop, September 2–3, 2009. Special thanks are given to the workshop planning committee forits contributions to the planning process.Acknowledgmentsv

ContentsAcknowledgments. vBackground. 1Workshop Goals and Objectives . . 1About Sickle Cell Disease. 3Sickle Cell Disease Research History. 5Strategy Development Workshop Overview. 9Charge to Workshop Participants: Small Group Sessions. 9Workshop Recommendations. 10Workshop Presentation Summaries. 11September 2, 2009. 11September 3, 2009. 21Recommendations for a Sickle Cell Disease Awareness and Education Campaign. 25Moving Forward. 26Appendix A: Workshop Agenda. 33Appendix B: Workshop Participants. 37Contentsvii

BackgroundThe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute(NHLBI) has long been committed to devel oping and maintaining research efforts thatim prove the lives of people who have sickle celldisease (SCD). Scientific advances have led toeffective approaches for the management andtreatment of SCD and the prevention of compli cations. As a result, people who have SCD livelonger and more productive lives than they didin the past. Consistent with goals described inits strategic plan, the NHLBI is reexaminingand realigning its research program on SCD toembark on a revitalized research portfolio ofbasic, clinical, and translational research.management, current and planned research in thefield, historical barriers to and opportunities forplanning a national awareness and educationcampaign, and an overview of Federal effortsrelated to SCD. In a moderated talk show format,SCD patients, family members, and health careproviders shared their personal experiences ofliving with and managing SCD. A panel presented information about three successful NHLBIawareness and education campaigns.Workshop Goals and ObjectivesGoalsnProvide the NHLBI with recommendations fordeveloping a national health awareness andeducation campaign to raise awareness aboutSCD and to bring nationwide attention to itsdiagnosis and treatment.The NHLBI is currently developing evidencebased guidelines for the care of people who haveSCD, which health care providers throughout theworld can use. In addition, the NHLBI will launcha public awareness and education campaign toraise awareness of and bring nationwide attentionto SCD. An essential component of this effort willbe to educate providers and patients about SCDdiagnosis and effective treatment options.nForm a strong coalition of stakeholders andFederal Agencies to partner with the NHLBIin implementing the SCD awareness andeducation campaign.As part of the campaign’s development, the NHLBIhosted a 2-day Strategy Development Workshopon September 2–3, 2009, in Bethesda, Maryland.The workshop brought together key stakeholders,including researchers, health care providers,advocacy organizations, patients, and otherinterested individuals, to help the NHLBI beginplanning a national awareness and educationeffort on SCD.nIdentifies the key target audiences.nOffers content for key messages appropriate toeach target audience.nProposes program strategies, settings,and channels for delivering the messages thatincrease awareness and change behaviors,along with measures for assessing programeffectiveness.Participants were charged with addressing keyissues for a national campaign relating to targetaudiences, messages, strategies, and partnerships.Presentations covered the history of SCD and itsnIdentifies potential partner organizations andpeople to work with the NHLBI in implementing and evaluating the campaign, and toexpand the Institute’s reach to desiredaudiences.ObjectivesProvide the NHLBI with a set of comprehensiverecommendations for a national health awarenessand education campaign that:Background1

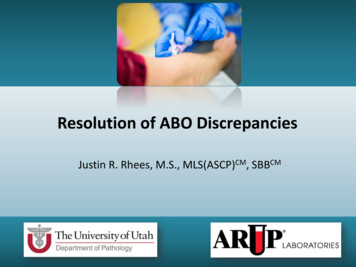

About Sickle CellDiseaseSickle cell disease (SCD), also known as sicklecell anemia, is a serious disease in which thebody makes an altered form of hemoglobin, theprotein in red blood cells that carries oxygenthroughout the body. This genetic alterationcauses the body to produce abnormal sickle- orcrescent-shaped red blood cells.A common misconception is that SCD is solelyan African American disease, but it also affectsHispanic Americans and other emerging populations in this country. The disease occurs in 1 outof every 36,000 Hispanic American births.1Exhibit 1. Normal and SickledRed Blood CellsUnlike normal red cells that pass smoothlythrough the blood vessels, sickle cells are stiff andsticky and tend to form clumps that get stuck inthe blood vessels and obstruct blood flow. Theresult is episodes of extreme pain (“crises”), as wellas chronic damage to vital organs.SCD is an inherited disease. People who have thedisease inherit two copies of the sickle cell gene—one from each parent. If a person inherits onlyone copy of the sickle cell gene (from one parent),he or she will have sickle cell trait. Sickle cell traitis different from SCD. People who have sickle celltrait do not have the disease, but they have oneof the genes that cause it. Like people who haveSCD, people who have sickle cell trait can pass thegene to their children.SCD is most common in people whose familiescome from Africa, South or Central America(especially Panama), Caribbean islands, Mediter ranean countries (such as Turkey, Greece, andItaly), India, and Saudi Arabia. In the UnitedStates, it is estimated that SCD affects about70,000 to 100,000 people, primarily AfricanAmericans. The disease occurs in about 1 outof every 500 African American births.1Figure A shows normal red blood cells flowingfreely in a blood vessel. The inset image showsa cross-section of a normal red blood cell withnormal hemoglobin.Figure B shows abnormal, sickled red bloodcells clumping and blocking blood flow in ablood vessel. (Other cells also may play a rolein this clumping process.) The inset imageshows a cross-section of a sickle cell withabnormal hemoglobin.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2008). Sickle cell anemia. Diseases and Conditions Index. Retrieved ca/SCA WhoIsAtRisk.htmlAbout Sickle Cell Disease3

About 2 million Americans have sickle cell trait.2This condition occurs in about 1 in 12,3 or 8 percent, of African Americans.4 5The severity of SCD varies from person to person.Some people who have the disease have chronicpain and/or fatigue. Many people who have SCDface a shortened life expectancy and a host ofrecurring, debilitating, and expensive health problems.6 The effects of sickle cell crises on differentparts of the body can cause a number of complications, including infections and organ damage.Two of the organs most susceptible to damageare the brain and the lungs. Strokes and a lifethreatening respiratory problem known as acutechest syndrome are frequent complications forpeople who have SCD. The disease also damagesthe spleen at a very early age, which impairs thebody’s immune system and makes young childrenextremely vulnerable to overwhelming bacterialinfections.SCD has no widely available cure, although bloodand marrow stem cell transplants or gene therapymay offer a cure in a small number of cases. Thereare treatments for the symptoms and complications of the disease. Over the past 100 years, doctors have learned a great deal about SCD. Theyknow its causes, how it affects the body, and howto treat many of its complications. Research isongoing to learn more about SCD and to find newtreatments for the disease.With proper care and treatment, many people whohave SCD can have improved quality of life and reasonable health much of the time. Due to improvedtreatment and care, people who have SCD are nowliving into their forties or fifties, or longer.2National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (1996). Facts about sickle cell anemia (p. 2) (NIH Publication No. 96-4057).Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from e/sca fact.pdf3National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (1996). Facts about sickle cell anemia (p. 2) (NIH Publication No. 96-4057).Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from e/sca fact.pdf4National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Pulmonary and vascular medicine branch. Retrieved from asp?5Gladwin, M. T., & Vichinsky, E. (2008, November 20). Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. New England Journal ofMedicine, 359(21), 2254–2265. Retrieved from 546National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2002). Sickle cell research for treatment and cure (pp. 3–4) (NIH PublicationNo. 02-5214). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from 0.pdf4Sickle Cell Disease Awareness and Education Strategy Development Workshop Report

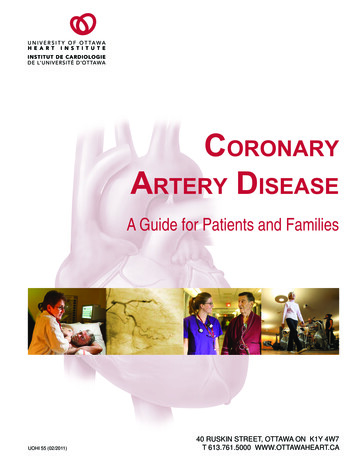

Sickle Cell DiseaseResearch HistoryIn 1971, President Richard Nixon made researchon sickle cell disease (SCD) a national priority.On May 16, 1972, the National Sickle Cell AnemiaControl Act was signed into law. It provided forthe establishment of voluntary sickle cell anemiascreening and counseling programs, informationand education programs for health professionalsand the public, and research training in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of sickle cell anemia.Shortly after the act was passed, the NationalSickle Cell Disease Program was established, andthe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute(NHLBI) was tasked with developing and supporting a program of research in SCD.Since that time, the NHLBI has committed morethan 1 billion to research on SCD. The Insti tute supports an extensive research program toimprove understanding of the pathophysiologyof SCD and to identify effective approaches for itsmanagement and treatment and for prevention ofcomplications.Areas of current interest include genetic influences on disease manifestations, regulation ofhemoglobin synthesis, development of drugs toincrease fetal hemoglobin production, transplantation of blood-forming stem cells, gene therapy,and development of animal models for preclinical studies. The NHLBI supports this researchthrough investigator-initiated projects and specialinitiatives.77This public investment in SCD research hasyielded significant returns, ranging from understanding fundamental biological and pathologicalprocesses to translating basic discoveries andclinical observations into clinical applications.Some examples of clinical benefits and researchdiscoveries include:nThe life expectancy of SCD patients doubledbetween 1972 and 2002.nProphylactic penicillin given to SCD patientsfrom birth to 5 years of age significantlyreduced sepsis and mortality.nTranscranial Doppler (TCD) screeningidentified children at increased risk for stroke.nPeriodic blood transfusions helped preventfirst-time and recurrent stroke in childrenwho had SCD and were at high risk for stroke.nHydroxyurea therapy in adults who had SCDresulted in a 50 percent reduction of thefrequency of pain, acute chest syndrome,hospitalizations for painful symptoms, andunits of blood transfused.nAllogeneic bone marrow transplants wereshown to cure the clinical symptoms of SCD.Despite significant clinical returns, a critical needstill exists for further research on SCD. This needis summarized in the conclusions of the conference statement for the February 2008 NationalInstitutes of Health Consensus DevelopmentConference on Hydroxyurea Treatment for SickleCell Disease:“The burden of suffering is tremendous amongmany patients who have sickle cell disease.These patients experience disease-related painon many days of their lives and usually do notseek medical attention until their symptomsNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2008). Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Advisory CouncilSubcommittee Review of the NHLBI Sickle Cell Disease Program. Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/scd program.htmSickle Cell Disease Research History5

are overwhelming. They often attempt to treatthemselves and thus do not always come to theattention of the healthcare system. Obtainingoptimal care for patients who have sickle celldisease is challenging. Many patients are not in acoordinated program aimed at prevention of longterm complications and acute pain crises. Theyrely heavily on emergency and acute care facilitiesfor pain control.“Obtaining specialty care can be a significant challenge as the number of health professionals trainedto treat the disease is limited and the number ofprofessionals specializing in the treatment of thisdisease is decreasing. The likelihood that patientswho have sickle cell disease have a principalphysician is low. Transitioning from pediatric careto adult care poses particular challenges. Manychildren rely on public insurance for their care.Gaps in coverage occur, leading to gaps in care.Exhibit 2. Selected Examples of ResearchNIH-Initiated Research6nSickle Cell Disease Clinical Research Network—initiated in fiscal year (FY) 2006 to facilitate translation of results from basic studies and phaseI/II clinical trials into phase III trials in patientswho have SCD; funding continues throughFY 2010.nPhase II/III Trial of Sildenafil for Sickle CellDisease-Associated Pulmonary Hypertension—initiated in FY 2006 as a complement to andextension of an NHLBI intramural trial to test theeffects of sildenafil therapy on exercise capacity and elevated pulmonary artery pressure inSCD patients who have pulmonary hypertension.This trial was stopped in July 2009 due to safetyconcerns. In an interim review of safety data, researchers found that, compared to participants onplacebo, participants taking sildenafil were morelikely to have serious medical problems, includingsickle cell crises.nPediatric Hydroxyurea Phase III Clinical Trial(BABY HUG)—initiated in FY 2000 to assess theeffectiveness of hydroxyurea in preventing chronicorgan damage in young children who have SCD;funding continues through FY 2010.nComprehensive Sickle Cell Centers—initiated in1972 to support multidisciplinary research andexpedite development and application of newknowledge for improved diagnosis and treatmentof SCD; 10 centers were funded through FY 2007.Investigator-Initiated ResearchnStroke With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (SWITCH)—initiated in FY 2005 to comparestandard therapy (transfusions and iron chelation)with alternative therapy (hydroxyurea and phlebotomy) for the prevention of secondary strokeand management of iron overload in children whohave sickle cell anemia.nStroke Prevention in Sickle Cell Anemia (STOP)—initiated in FY 1994 to determine whether periodicblood transfusions were more effective at preventing stroke than standard supportive care.nSibling Donor Cord Blood Banking and Transplantation—initiated in FY 2001 to collect cord bloodfrom sibling donors in families with children whohave SCD or thalassemia with the intent of futuretransplantation.nStroke Prevention in Sickle Cell Anemia(STOP 2)—initiated in FY 2000 to determinewhether blood transfusions must continue orcould be stopped and when.Sickle Cell Disease Awareness and Education Strategy Development Workshop Report

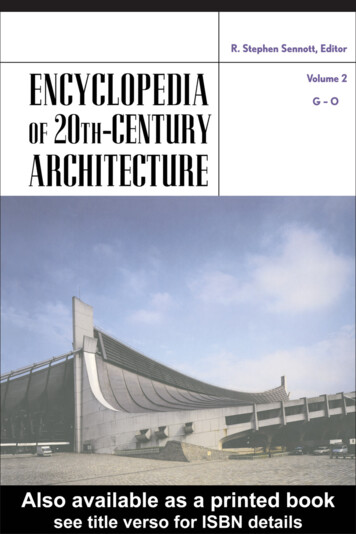

“No population-based registries exist that providegood estimates of the number of people who havesickle cell disease. Surveys indicate that a largeproportion of patients who have sickle cell diseaseare poor and from underserved communities.Most U.S. patients who have sickle cell disease areethnic minorities. For many, the limited resourcesand lack of culturally competent care by experienced clinicians set the stage for suboptimal care.“The best way to achieve optimal care for patientswho have sickle cell disease, including preventive care, is for the patients to be treated in clinicsspecializing in the care of this disease. All sicklecell patients who have sickle cell disease shouldhave a principal healthcare provider, and that provider, if not a hematologist, should be in frequentconsultation with one.”8Exhibit 3. Increases in Life Expectancy of Patients Who HaveSickle Cell Disease70All Americans60Life Expectancy (years)80504030Sickle 80YearSickle cell diseasesare identified1990The life expectancy ofpatients who have sickle celldisease has doubled sincethe passage of theNational Sickle CellAnemia Control Act.2000STOP study shows that frequent bloodtransfusions can lower rate of stroke by90 percentCongress passes the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control ActNHLBI-supported researchers demonstratethat bone marrow transplantation canprovide a cure for young sickle cell patients(ages 3–14) who have a matched siblingThe NHLBI establishes Comprehensive Sickle Cell CentersFirst statewide newborn screening program is implementedPROPS shows that prophylactic administration of penicillinto children prevents pneumococcal infectionMSH shows that hydroxyurea treatmentreduces painful episodes in severelyaffected adults who have sickle cell diseaseSource: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2002). Sickle cell research for treatment and cure(p. 15) (NIH Publication No. 02-5214). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.8National Institutes of Health. (2008). NIH Consensus Development Conference: Hydroxyurea treatment for sickle cell disease.Final statement. Retrieved from htmSickle Cell Disease Research History7

Strategy DevelopmentWorkshop OverviewThe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute(NHLBI) convened a 2-day workshop inSeptember 2009 to elicit recommendations fromsickle cell disease (SCD) stakeholders for the development of a national awareness and educationcampaign. The NHLBI charged participants withaddressing a number of key questions that wouldhelp inform the SCD campaign. These questionsconcerned target audiences, messages, communication strategies, and partnerships.On the first day of the workshop, the NHLBIDirector, Dr. Elizabeth G. Nabel, reviewed thehistory of SCD and past and current NHLBIresearch efforts. Speakers then addressed themeeting’s call to action and historical barriers toand opportunities for creating a national campaign. They also provided an overview of otherSCD education and outreach efforts. During amoderated talk show, several people living withSCD, a family member caring for children whohave SCD, and clinicians providing care for SCDpatients shared their personal experiences ofliving with and managing the disease.A panel presentation informed the audienceabout the health communication process used inthree successful NHLBI awareness and educationcampaigns—focusing on women’s heart health,chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),and peripheral arterial disease (P.A.D.)—and thecritical role of formative research in campaigndesign. Finally, an overview of existing SCDcampaigns and other major educational effortswas presented. Following the presentations,participants broke into five small working groupsto address two key questions related to targetaudiences and campaign messages.Presentations on the second day of the workshopcovered an overview of the NHLBI’s SCD researchefforts in conjunction with the Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention (CDC) and the HealthResources and Services Administration (HRSA).Following these presentations, attendees againbroke into small working groups to consider twofinal key questions pertaining to strategies andsettings for message delivery and potentialpartners. In closing, Dr. W. Keith Hoots, Directorof the NHLBI Division of Blood Diseases andResources, summarized workshop activities andoutlined the NHLBI’s next steps for developingand implementing a national awareness andeducation effort.Charge to WorkshopParticipants: Small GroupSessionsParticipants were asked to consider the followingquestions and make related recommendations fordeveloping a comprehensive campaign strategy.1. Who are the key target audiences for thecampaign? The NHLBI sought to determinethe audiences most in need of informationand education, and those for whom outreachefforts could have the greatest effect. Participants were asked to consider any and all audiences and subsets of audiences, both publicand professional.2. What are the most significant messages foreach target audience identified? The NHLBIsought input on the focus of a national effort. Participants were asked to recommendwhether the campaign should primarily havean awareness or education focus. Based onthe recommended focus, participants wereasked to propose the most significant messages needed for each target audience identified.Strategy Development Workshop Overview9

3. What national strategies, communitysettings, and channels should the NHLBIdevelop for a national awareness andeducation campaign? The NHLBI soughtrecommendations on strategies and com munication channels for effectively disseminating the campaign’s key messages andreaching the target audience(s).education campaign. As they worked in smallgroups, they were able to make broad recommendations about target audiences, messages, implementation strategies, and partnerships. Althoughno single target audience emerged as a priority,the following three audiences were deemed essential: people who have SCD and their families, thegeneral public, and health care providers.4. Which organizations would make the bestpotential partners for helping the NHLBIimplement, sustain, and evaluate the campaign? Partner organizations can help theNHLBI vastly expand its reach to the targetaudience(s). These organizations also canserve as trusted intermediaries for the dissemination and delivery of messages and materialsto desired audiences. Workshop participantswere asked to identify organizations thatmight contribute to the implementation of theSCD campaign.Other general recommendations stemming fromsmall-group discussions included the following:Workshop RecommendationsMeeting participants enthusiastically embracedtheir charge to develop priority recommendations for creating a national SCD awareness and10nRaise awareness among affected populationsabout treatment and management options.nRaise awareness among targeted segments ofthe general public about SCD, sickle cell trait,and their implications.nEncourage people affected by SCD to becomeempowered about their own health and seekappropriate medical care.nEducate primary health care providers aboutthe management of and new standards of carefor patients of all ages who have SCD.Sickle Cell Disease Awareness and Education Strategy Development Workshop Report

Workshop PresentationSummariesUnited States, mainly African Americans.SCD occurs in approximately 1 out of every500 African American births and 1 out of every36,000 Hispanic American births. In addition,about 2 million people in the United States havesickle cell trait and can pass the sickle cell gene totheir offspring.Presentations at the September 2009 workshopcovered past, current, and future plans forFederal programs and research related to sicklecell disease (SCD), perspectives from people affected by SCD and providers working with SCDpatients, and an overview of other National Heart,Lung, and Blood Institute awareness and education efforts. These presentations were designedto set the stage for deliberations that would takeplace in the small working group sessions.Sections that follow provide summaries of contentfrom the workshop’s plenary sessions.September 2, 2009Welcome and IntroductionElizabeth G. Nabel, M.D., Director, NationalHeart, Lung, and Blood InstituteThe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute(NHLBI) believes in the importance of nationaleducation campaigns and has a history of measurably successful campaigns on topics such as hearthealth, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This workshop serves as amilestone and starting place for development ofa dynamic and effective sickle cell disease (SCD)awareness and education effort.SCD is an extremely serious, chronic disease thataffects people in the United States and throughoutthe world. The disease is especially prevalent inAfrican American, Central and South American,Mediterranean, and Saudi Arabian populations.Although considered rare, it is estimated thatSCD affects 70,000 to 100,000 people in the“Sickle cell has a profoundimpact, not just on thepatient, but on the wholefamily dynamic.”—Stephanie Davis, M.D.Although SCD is known to have existed earlier,Chicago cardiologist and professor of medicineJames B. Herrick first noted the cell irregularity in his research in 1910. In 1949, Dr. LinusPauling and colleagues showed that SCD resultsfrom a hemoglobin molecule abnormality andcoined the term “molecular disease” to describeSCD. By the 1970s, management of the diseasehad grown to include blood transfusions, fluidmanagement, and analgesic therapy. In 1972,under the National Sickle Cell Anemia ControlAct, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) beganSCD research studies. Findings from these studiesled to a dramatic increase in life expectancy forpeople who had SCD. Since then, key researchmilestones have included:n1982: Newborn screening was established inthree U.S. States.n1983: Efficacy of oral penicillin and confirmation of the importance of early diagnosisand treatment were demonstrated.n1991: Compelling results were demonstratedfrom a multisite study on treatment withhydroxyurea.Workshop Presentation Summaries11

nn1995: A stroke prevention study yieldedstrong evidence for the value of Dopplerultrasound in stroke prevention.2000: Use of ultrasound for stroke showedprogress in reducing pain, increasing lifespan,and improving quality of life for people whohave SCD.Today, research has confirmed that hydroxyureais a valuable treatment for adults. BABY HUG, apediatric clinical trial for the use of hydroxyureain babies, is just being completed; another, longerstudy is planned. In addition, the NHLBI currentlyis undertaking a major effort with the Centers forDisease Control and Prevention to develop andimplement a registry and surveillance system inhemoglobinopathies (RuSH). RuSH will be a national data system with a surveillance component,a registry system, and a biospecimen repositorythat will provide data to describe the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of people whohave all genotypes of SCD, thalassemias, and otherhemoglobinopathies. The first phase of the projectwill be to conduct pilot studies in five to six Statesto test specific data collection methods, procedures,and organizational structures. This phase also willdetermine the feasibility of implementing RuSH ona national level.The development of SCD guidelines is one ofseveral priority areas for the NHLBI. The NHLBIplans to communicate the guidelines to primaryhealth care providers and the general public,people who have SCD or sickle cell trait, and theirfamilies, advocates, and the media. This workshop—the first step in this communicationeffort—will help the NHLBI identify key targetaudiences, messages, and implementationstrategies at local, national, and internationallevels. The workshop also will help forge partnerships to help the Institute achieve (and measure)success.12A Call To ActionLanetta Jordan, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.P.H.,Chief Medical Officer, Sickle Cell DiseaseAssociation of AmericaThe Sickle Cell Disease Association of America(SCDAA) has been the leading nonprofit consumerorganization focusing on sickle cell disease (SCD)since 1971. The SCDAA has worked for nearly fourdecades to develop a coordinated national approachand partner with community-based organizationsto provide information and support to people affected by SCD and their families.“Children need to be treateddifferently from adults; rightnow there is a huge disconnect between childhood

Sickle Cell Disease . Awareness and Education Strategy Development Workshop Report. Pu