Transcription

RECONSTRUCTIVEPatient-Related Keloid Scar Assessment andOutcome MeasuresFootAQ: 3AQ: 1Rebecca S. Nicholas,M.B.B.S.Hannah Falvey,B.Sc.(Hons.), D.Clin.Psychol.Pambos Lemonas, M.D.,M.R.C.S.Gopinath Damodaran,B.Sc., Ph.D.Ali Ghannem, M.R.C.S.,M.D., Ph.D.Florendyn Selim,Harshad Navsaria, Ph.D.Simon Myers, Ph.D.,F.R.C.S.(Plas.)London, United KingdomBackground: Keloid scars cause pain, itching, functional limitation, and disfigurement, leading to psychological distress. Progress in treatment regimens is hindered by the lack of a universally accepted outcome measure. The Patient andObserver Scar Assessment Scale is a tool for the assessment of scars that includesscar assessment by both clinician and patient. This study evaluates the applicationof the scale to keloid scars, in addition to comparing it to the widely used VancouverScar Scale which, although originally designed for burns, is in wide use in many unitsacross the world as the standard mode of assessment for scars.Methods: Thirty-four patients with 41 keloid scars were assessed independently bythree observers using the Vancouver Scar Scale and the Patient and Observer ScarAssessment Scale. Patients evaluated their own scars simultaneously using the patient component of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. Internalconsistency, interobserver reliability, and convergent validity were examined.Results: Both components of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scalehad high internal consistency (0.82 and 0.86 for patient and observer components, respectively), and were higher than the Vancouver Scar Scale (0.65).Interobserver reliability was “substantial” for the Vancouver Scar Scale (0.65)and “almost perfect” for the observer component of the Patient and ObserverScar Assessment Scale (0.85). Convergent validity between the two was verystrong (0.83, p ! 0.01), although the patient component did not correlate wellwith either of the observer scales. Patients rated their scars worse than theobserver average for 83 percent of the scars, and were influenced by color,stiffness, thickness, and irregularity (p ! 0.05).Conclusion: The findings support the use of the Patient and Observer ScarAssessment Scale as a reliable and valid method of assessing keloid scars in aclinical context. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129: 1, 2012.)CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Diagnostic, II.Keloid scars arise from pathologic woundhealing following trauma and inflammation, and occur most commonly in thosewith darker pigmented skin. The resulting raised,irregular clusters of scar tissue extend well beyondthe original wound margins, and their color isoften discrepant to the surrounding skin, leadingto significant disfigurement. The scars are associated with physical discomfort (pruritus and pain),functional limitation (particularly when locatedover joints), and significant psychological morbidity associated with their disfiguring appearance.1,2From the Academic Burn and Microsurgery Group, BlizardInstitute of Cell and Molecular Science.Received for publication May 6, 2011; accepted September21, 2011.Copyright 2012 by the American Society of Plastic SurgeonsDOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182402c51Keloid scars are notoriously difficult to treat. Extralesional surgical excision alone results in recurrence that can be worse than the original lesion.Other therapeutic methods include intralesionalexcision (debulking), extralesional excision andexternal superficial radiotherapy, interstitial irradiation, intralesional steroid injections, systemicchemotherapy, cryotherapy, ultrasound, zinc tapestrapping, pressure garments, and silicone gels.Despite the wide range of therapeutic methodsavailable, keloid scars typically remain refractoryto treatment and have a high rate of recurrence.In addition, treatment complications such as localatrophy following steroid injections and late tu-Disclosure: The authors have no financial interestto declare in relation to the content of this r00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlm1

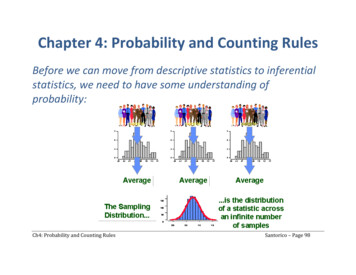

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery March 2012F1mor induction following radiotherapy are wellrecognized.1,3,4Progress in the identification of effective treatment regimens through clinical research has beenhampered by the lack of a universally acceptedmethod of measuring outcome.5,6 In addition,much research has focused on improving physicaloutcomes as judged by the clinician, although verylittle is known about whether such outcomes areperceived by patients as satisfactory. A suitable,feasible, and reproducible outcome measure inwide use would both allow comparison of keloidscar treatment outcomes across different clinicalsites and also be useful in the local clinical settingfor measuring individual patient responses totreatment.The specialist keloid service at the Royal LondonHospital is probably the largest multidisciplinary keloid clinic in Europe. The ethnically diverse communities surrounding the hospital present a highincidence of patients with keloid scars.The Vancouver Scar Scale, first described bySullivan et al. in 1990 (Fig. 1),7 has become one ofthe most widely applied scar assessment scales inclinical research.5 Although originally designedfor burns, the Vancouver Scar Scale has beenfound to be clinically useful in evaluating a widerange of scar types and has become established inmany units across the world as the standard modeof assessment. It allows assessment of pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, and scar height. Each ofthese variables is relevant to keloid scars which,without treatment, are typically pigmented, vascular (especially apparent in patients with light skintones), stiff, and raised. In our clinical experience,each of these scar characteristics can respond positively to effective treatment, producing paler, lessred, more supple, and flatter scars. Although theVancouver Scar Scale is simple to use in a clinicalsetting and is well received by clinicians, it does notallow assessment of the patient perspective or symptoms associated with the scar, which are particularlyrelevant to keloid scar patients. The newer Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale is a scar evaluation tool that allows assessment of the same observed scar characteristics as the Vancouver ScarScale in addition to incorporating the patient perspective (Figs. 2 and 3).8,9 For this reason, it is apotentially promising tool for the assessment of keloid disease. This study evaluates the application ofthe Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale tokeloid scars and compares it to the widely used Vancouver Scar Scale in a clinical setting.PATIENTS AND METHODSThirty-four patients attending the specialistkeloid service at The Royal London Hospital,Whitechapel, Barts and The London NHS Trustwere assessed as part of routine clinical practicebetween June 15 and July 15, 2010. Their meanage was 33 years (median, 29 years; range, 17 to 56years). A total of 41 keloid scars were evaluated: 11on the ear, 10 presternal keloids, eight on theshoulder, four on the anterior abdominal wall,four on the lower limb, two on the face, one on thebreast, and one nuchal keloid. The surface area ofthe scars ranged from 25 mm2 (5 " 5-mm scar) to21,700 mm2 (155 " 140-mm scar). Median surfacearea was 825 mm2. Five patients (15 percent) hadFitzpatrick skin type I to IV (white-beige skintone), and 29 patients (85 percent) had Fitzpatrick skin type V to VI (brown-black skin tone).10Seven patients were new to the clinic and hadreceived no previous treatment. Most patientswere already undergoing treatment with intralesional steroid injections: on average, patients hadreceived six previous injections.Fig. 1. The Vancouver Scar Scale.2Scar Assessment ScalesAll scars were assessed independently by threeobservers (one clinical nurse specialist, one spe-F2-3

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmVolume 129, Number 3 Patient-Related Keloid Scar AssessmentFig. 2. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: Patient scale.F4cialist registrar in plastic surgery, and one finalyear medical student) on the same day and usingboth the Vancouver Scar Scale and the Patient andObserver Scar Assessment Scale (observer component). The three observers were blinded to eachothers’ scores. These scoring scales are shown inFigures 1 through 3. Each scar scale allowed theobserver to rate a number of physical characteristics on a numerical scale. The Vancouver ScarScale had four components—vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height—to give a total scarscore ranging from of 0 to 13 (where 0 representsnormal skin).7The Observer Scar AssessmentScale rates six physical characteristics—vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, thickness, relief, andsurface area—in addition to an “overall opinion”component. The total score was calculated as asum of all seven components of the scale, to givea score of 7 to 70 (where 7 represents normalskin).9 Examples of three keloid scars and corresponding observer scores are shown in Figure 4.Patients were asked to rate their own scars onthe same day as the observers, using the patientcomponent of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. They were blinded from the observers’ scores. This part of the scale asked thepatient to rate four physical characteristics of theirscar— color, stiffness, thickness, and irregularity(defined as “bumpiness—in addition to two symptom scales for pain and itching associated with thescar. Patients were also asked to rate their “overallopinion” of their scar. As for the observer scale,each component was rated 1 to 10, with the totalcalculated as a sum of all scale components (7 to70, where 7 represents normal skin without associated pain or itching).9Statistical AnalysisThe data were analyzed using the statisticalprogram PASW 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.).Cronbach’s !, a reliability coefficient, was used tomeasure internal consistency for each of the twoscales.11 Internal consistency is defined as the extent to which a set of items—in this case, the scalecomponents— behave as a group. If the value ishigh, this is evidence that the scale componentsmeasure the same underlying construct. A reliability coefficient of 0.70 or higher is considered“acceptable.”12,13Interobserver reliability is the degree to whichassessments from two or more observers agree.3

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery March 2012Fig. 3. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: Observer scale.AQ: 4This was measured by calculating the intraclasscorrelation coefficient using a two-way mixedmodel with measures of consistency. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated bothfor single observer (single measure) and for thethree observers (average measure). In evaluatingthis, a correlation coefficient of 0 to 0.2 was interpreted as “slight”; 0.21 to 0.40, “fair”; 0.41 to0.60, “moderate”; 0.61 to 0.80, “substantial”; and0.81 to 1.0, “almost perfect.”14Convergent validity refers to the degree towhich a rating is similar to another independentlygathered rating to which it should be theoreticallysimilar. We used the Pearson correlation coefficient to determine the degree of correlation between each of the components of the VancouverScar Scale and both parts of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale.15We performed simple linear regression analysis to identify factors that significantly influenced4patients’ overall opinion of their scars. In additionto examining each component of the Patient ScarAssessment Scale (scar-related pain, itchiness,color, stiffness, thickness, and irregularity), theamount of treatment received to date (number ofsteroid injections—the mainstay of treatment inthe keloid clinic), and the scar surface area werealso tested in the regression model.16RESULTSInternal ConsistencyBoth components of the Patient and ObserverScar Assessment Scale were found to have relatively high internal consistency, with reliability coefficients of 0.82 for the patient component and0.86 for the observer component. However, a reliability coefficient of only 0.65 was found for theVancouver Scar Scale, suggesting that the scaleitems have relatively low internal consistency.

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmVolume 129, Number 3 Patient-Related Keloid Scar AssessmentFig. 4. Examples of keloid scars and corresponding observer scores. (Left) Total score, 55 of 70. Componentsinclude vascularity, 9 of 10; pigmentation, 6 of 10 (vascularity differentiated from pigmentation by physicallyblanching the scar and observing dark pigmentation when blanched, then extent of capillary refill on release);thickness, 7 of 10; relief, 8 of 10; pliability, 8 of 10; surface area, 8 of 10; and overall opinion, 9 of 10. (Above, right)Total score, 16 of 70. Components include vascularity, 2 of 10; pigmentation, 1 of 10; thickness, 2 of 10; relief, 1of 10; pliability, 2 of 10; surface area, 6 of 10; and overall opinion, 2 of 10. (Below, right) Total score, 33 of 70.Components include vascularity, 1 of 10; pigmentation, 1 of 10; thickness, 8 of 10; relief, 1 of 10; pliability, 8 of 10;surface area, 8 of 10; and overall opinion, 6 of 10.T1Interobserver ReliabilityThe interobserver reliability of the VancouverScar Scale and the observer component of thePatient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale aresummarized in Table 1. The intraclass correlationcoefficient was consistently greater for the groupof three observers (average measure) comparedwith the single observer (single measure). Looking at the total score for each of the scales, interobserver reliability was “substantial” for the Vancouver Scar Scale, and “almost perfect” for theobserver component of the Patient and ObserverScar Assessment Scale. For the individual Vancouver Scar Scale variables, the interobserver reliability was “almost perfect” for pigmentation andheight, “moderate” for pliability, but only “slight”for vascularity. For the observer component of thePatient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale, interobserver reliability was “almost perfect” for pliability, surface area, and overall opinion; “substantial” for pigmentation, thickness, and relief; and“moderate” for vascularity.Convergent ValidityAs Table 2 shows, the two scales had a strongcorrelation with each other, with values of p ! 0.01for all. The scores for pliability and height had thestrongest correlation coefficients (0.88 and 0.85,respectively), whereas correlations for pigmentation and vascularity scores were the lowest of thegroup of variables (0.64 and 0.70, respectively).5T2

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery March 2012Table 1. Interobserver Reliability of the VancouverScar Scale and the Observer Component of thePatient and Observer Scar Assessment ScaleSingleMeasure ICC(95% CI)AverageMeasure ICC(95% CI)Vancouver ScarScaleVascularity0.054 (–0.11–0.26)*Pigmentation0.59 (0.43–0.74)§Pliability0.34 (0.15–0.54)†Height0.69 (0.55–0.81)§Total score0.38 (0.19–0.57)‡Observercomponent ofthe POSASVascularity0.24 (0.05–0.45)†Pigmentation0.54 (0.36–0.7)‡Pliability0.59 (0.43–0.74)‡Thickness0.57 (0.4–0.72)‡Relief0.43 (0.245–0.61)‡Surface area0.60 (0.43–0.75)‡Overall opinion 0.66 (0.51–0.79)§Total score0.66 (0.51–0.79)§AQ: 50.14 (–0.43–0.51)*0.82 (0.69–0.89)!0.60 (0.34–0.78)‡0.87 (0.78–0.93)!0.65 (0.41–0.80)§0.49 (0.15–0.71)‡0.77 (0.62–0.87)§0.81 (0.69–0.89)!0.80 (0.66–0.88)§0.70 (0.50–0.83)§0.82 (0.70–0.90)!0.85 (0.76–0.91)!0.85 (0.76–0.91)!CI, confidence interval; Single Measure ICC, intraclass correlationcoefficient for a single observer; Average Measure ICC, intraclasscorrelation coefficient for the group of three observer; POSAS, Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale.Key: *slight; †fair; ‡moderate; §substantial; !almost perfect.Table 2. Correlation between the Vancouver ScarScale and the Observer Component of the Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale*VSS pigmentation score vs. OSASpigmentation scoreVSS vascularity score vs. OSASvascularity scoreVSS pliability score vs. OSASpliability scoreVSS height score vs. OSAS thicknessscoreVSS total score vs. OSAS total .010.88!0.010.850.83!0.01!0.01VSS, Vancouver Scar Scale; OSAS, Observer Scar Assessment Scale.*All 41 scars, all three observers.T3Correlation between each of the observerscales and the patient component of the Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale were not statistically significant for any of the variables oneither scale (Table 3). However, it was notable thatpatients’ total scores were higher than the averageobserver total for the same scar in 83 percent ofcases (n # 33).Patient Scar Assessment ScaleForty-three percent of patients reported thattheir scar had been painful over the preceding fewweeks, and scar-related itching was reported by 706Table 3. Correlation between the Patient andObserver Scores Using the Vancouver Scar Scale andthe Observer Component of the Patient andObserver Scar Assessment ScaleVSS pliability score vs. PSAS stiffnessscoreVSS pigmentation score vs. PSAScolour scoreVSS vascularity score vs. PSAS colourscoreVSS height score vs. PSAS thicknessscoreVSS total score vs. PSAS total scoreOSAS pliability score vs. PSAS stiffnessscoreOSAS pigmentation score vs. PSAScolour scoreOSAS vascularity score vs. PSAS colourscoreOSAS thickness score vs. PSAS thicknessscoreOSAS total score vs. PSAS total .180.150.260.34VSS, Vancouver Scar Scale; PSAS, Patient Scar Assessment Scale;OSAS, Observer Scar Assessment Scale.percent of patients. Almost all patients reportedthat scar color (93 percent), thickness (95 percent), stiffness (98 percent), and surface irregularity (98 percent) were different from their normal skin, and at least half of the patients (53, 50,50, and 50 percent, respectively) rated these physical scar characteristics as very different from theirnormal skin (8 to 10 of 10). Seventy percent ofpatients had an overall opinion of their scar of 8to 10 of 10.Simple Linear Regression AnalysisTable 4 shows that patients’ overall opinion oftheir scars was significantly influenced by scarcolor, stiffness, thickness, and irregularity (p !Table 4. Simple Linear Regression Analysis ofVariables Associated with the Patient ScarAssessment Scale*Patient ainItchinessNo. of treatmentsScar surface areaCoefficient ofDetermination(r2)SlopeCoefficient �†*Dependent variable: patient’s overall opinion of scar.†Not significant (p 0.05).T4

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmVolume 129, Number 3 Patient-Related Keloid Scar Assessment0.05 for all), with color, thickness, and irregularitybeing the strongest determinants of the variationin overall opinion [coefficients of determination(r 2) of 0.24, 0.21, and 0.32 respectively]. Theinfluence of scar-related pain, itchiness, numberof treatments, or scar surface area on patients’overall opinion was not shown to be significant(p 0.05).DISCUSSIONA simple and reproducible way of assessingkeloid scars in routine clinical practice is neededto monitor treatment outcomes. An accurate anduniversally accepted method of keloid scar assessment will assist the development of improvedtreatment regimens. Such an assessment tool mustbe valid, consistent, reliable, and feasible for usein the outpatient clinic setting.The Vancouver Scar Scale is a widely respectedand commonly used scar assessment scale.5,7,8,17Before this study, it was the scar assessment tool ofchoice in the Royal London Hospital KeloidClinic. However, the Vancouver Scar Scale fails tocapture clinical information from the patient’sperspective, the importance of which is increasingly being recognized as we seek to attain patientsatisfaction with scar outcome.18 For this reason,the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale isa promising new scar assessment scale, as it combines an observer’s clinical assessment with patient evaluation.This study is the first to evaluate the application of the Patient and Observer Scar AssessmentScale for the assessment of keloid disease specifically. It provides evidence to support the use ofthe Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scalefor the assessment of keloid scars; when comparedwith the current best available observer scale, theVancouver Scar Scale, the Patient and ObserverScar Assessment Scale observer componentshowed excellent concurrent validity. In addition,the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scalewas shown to have a number of advantages overthe Vancouver Scar Scale. In particular, it scoredhigher on measures of internal consistency andreliability: both components of the Patient andObserver Scar Assessment Scale were found tohave excellent internal consistency, whereas theresults for the Vancouver Scar Scale failed to demonstrate acceptable internal consistency. A lack ofconsistency of the Vancouver Scar Scale was alsofound by Draaijers et al. in 2004.8 They suggestedthat this may be attributable to the pigmentationvariable on the Vancouver Scar Scale appearingnominal, rather than being a “proper numericalscale” as seen on the Patient and Observer ScarAssessment Scale. However, on reviewing the original article that first describes the Vancouver ScarScale, the rationale for the pigmentation score isexplained: hypopigmentation scored 1, as it wasdeemed to be less significant than hyperpigmentation (scoring 2) for white, Indian, and Asianpopulations.7 However, as keloid disease predominates in extreme Fitzpatrick skin types (those withdarker skin), this original rationale for pigmentation in the Vancouver Scar Scale does not seemapplicable: hypopigmentation can be just as disfiguring for patients with dark skin as extremehyperpigmentation in lighter skin. The Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale scores pigmentation ranging from the patient’s normal skincolor (score of 1) to the opposite or most differentextreme of pigmentation (score of 10) and therefore seems more suitable for the assessment ofaltered scar pigmentation in a population comprising diverse Fitzpatrick skin types. Furthermore, the interobserver reliability of the Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale completedboth by multiple observers and by a single observerwas significantly better than the Vancouver ScarScale. Perhaps, as would be expected, the interobserver reliability for both the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale and the VancouverScar Scale was better for three observers than fora single observer, but the reliability for three observers was “almost perfect” for the Patient andObserver Scar Assessment Scale and only “substantial” for the Vancouver Scar Scale. The reliability of the observer scale for a single observerwas 0.66 for the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale— higher than for the Vancouver ScarScale (0.38). Although this does not quite meetthe recommended value of 0.70, it is worth notingthat it is higher than the results for a comparablestudy that concluded the Patient and ObserverScar Assessment Scale had “acceptable interobserver reliability” with 0.33 for a single measureand 0.60 for an average measure with threeobservers.19 Consequently, it seems there needs tobe greater agreement in such evaluations regarding what degree of reliability is “acceptable” forclinical practice.The Patient Scar Assessment Scale showed excellent internal consistency; however, it did notcorrelate well with the observer scales. This in itselfis a valuable finding because, as clinicians, we maythink we know what the patient perceives as asuccessful outcome when in fact our views can bedifferent from those of our patients. On the whole,patients thought worse of their scars than did the7

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmPlastic and Reconstructive Surgery March 2012observers, and most had a very negative overallopinion. A similar discrepancy between observerand patient scores was noted in the 2005 article byvan de Kar et al., who suggested this could bepartly attributed to itching and pain.9 However,unlike the study by van de Kar et al., here patients’overall opinions were not shown to be significantlyinfluenced by pain and itching. Instead, we suggest that patients’ impression of their scar may berelated to the degree of psychological distress associated with the visible disfigurement caused bykeloid disease, as patients’ overall opinion wasmost strongly influenced by the visible characteristics of their scars. Anecdotally, when completingthe self-assessment scale, many of the patients involved in this study expressed a wish to describethe wider impact of their keloid scars on their life,mentioning factors such as clothing, relationships,and social activities. This merits further study, witha view to possibly incorporating such factors intothe patient assessment scale for keloid scars.It is important that any tool that forms part ofroutine clinical assessment is feasible for use in abusy outpatient clinic setting. In this study, giveninitial training and some practice, we found thatthe Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scalewas quick and easy to use. From our experience ofusing the scale in a busy clinical setting, we recommend some amendments to the scale proforma that we found helpful: to make a clear distinction between the numerical score and the additional clinical information under the six category headings, we reformatted the scale to makethe order of completion clear. In addition, observers found it helpful to annotate the pro formawith the definitions and clarifications provided bythe authors (Figs. 2 and 3). As the meaning of theterm “relief” was not immediately clear to all usersof the scale, we recommend renaming this category “surface irregularities” or “bumpiness,” as defined by the original authors.20 Figure 5 showsguidelines that we adapted from the original pub-Fig. 5. Guidelines for completion of the observer component of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale.8F5

rich3/zpr-prs/zpr-prs/zpr00312/zpr5320-12z xppws S!1 1/15/12 23:37 4/Color Figure(s): F4 Art: PRS204008 Input-nlmVolume 129, Number 3 Patient-Related Keloid Scar Assessmentlication after consultation with the authors on areas of potential confusion.9,20 This was used fortraining observers. We recommend that the original authors might supplement this with an officialtraining package, complete with “anchor photographs” correlating to each 1-to-10 scale component. This would improve training and enhancethe reliability of the scale. We also suggest a patient-friendly instruction guide to assist patientswho are new to using the patient component thescale. Finally, “overall opinion”, although notstrictly a clinical parameter, was a particularly useful indicator of response to treatment in a clinicalsetting. This article demonstrates that the inclusion of this category in the total score does notdetract from the scale’s reliability or validity, andwe would therefore advocate its inclusion in thetotal score.CONCLUSIONSFor the assessment of keloid scars, the Patientand Observer Scar Assessment Scale is associatedwith high internal consistency and “almost perfect” interobserver reliability. It is more comprehensive than the Vancouver Scar Scale, which hadlower internal consistency and lower interobserverreliability by comparison. Neither scale correlatedwell with patients’ ratings, although the patientcomponent of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale provides valuable clinical information about the patient’s symptoms and perspectiveon their scar, which is currently missing from anyother scar assessment scoring system. The findingsof this study support the use of the Patient andObserver Scar Assessment Scale as a more useful,reliable, and valid method of assessing keloid scarsin a clinical context.AQ: 2Pambos Lemonas, M.D., M.R.C.S.The Barts and the London NHS TrustWhitechapelLondon E1 1BB, United KingdomACKNOWLEDGMENTThis study was supported by the Healing Foundation in association with the British Association of Plasticand Reconstructive Surgeons.REFERENCES1. Datubo-Brown DD. Keloids: A review of the literature. Br JPlast Surg. 1990;43:70–77.2. Butler PD, Longaker MT, Yang GP. Current progress inkeloid research and treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:731–741.3. Lahiri A, Tsiliboti D, Gaze NR. Experience with difficultkeloids. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:633–635.4. Mustoe TA. The patient and observer scar assessment scale:A reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast ReconstrSurg. 2004;113:1966–1967.5. Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, Levinson H. A review ofscar scales and scar measuring devices. J Plast Surg. 2010;10:354–363.6. Idriss N, Maibach HI. Scar assessment scales: A dermatological overview. Skin Res Technol. 2009;15:1–5.7. Sullivan T, Smith J, Kermode J, McIver E, Courtemanche DJ.Rating the burn scar. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990;11:256–260.8. Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, et al. The patientand observer scar assessment scale: A reliable and feasibletool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1960–1965; discussion 1966–1967.9. van de Kar AL, Corion LU, Smeulders MJ, Draaijers LJ, vander Horst CM, van Zuijlen PP. Reliable and feasible evaluatio

The Vancouver Scar Scale, first described by Sullivanetal.in1990(Fig.1),7 hasbecomeoneof the most widely applied scar assessment scales in clinical research.5 Although originally designed for burns, the Vancouver Scar Scale has been found to be clinically useful in evaluating a wide range of scar types and has become established in