Transcription

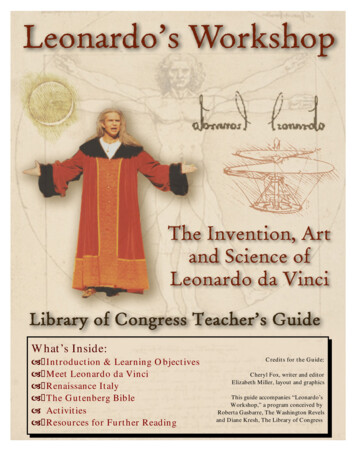

What’s Inside: Introduction & Learning ObjectivesMeet Leonardo da VinciRenaissance ItalyThe Gutenberg BibleActivitiesResources for Further ReadingCredits for the Guide:Cheryl Fox, writer and editorElizabeth Miller, layout and graphicsThis guide accompanies “Leonardo’sWorkshop,” a program conceived byRoberta Gasbarre, The Washington Revelsand Diane Kresh, The Library of Congress

IntroductionThe life and works of artist and scientistLeonardo da Vinci continue to fascinate usbecause, while he exemplified the ItalianRenaissance, he transcended his time and place,inventing things like a helicopter 500 years beforethe technology existed to build one. Thisperformance invites you to visit the workshop ofLeonardo’s mind where you can learn how a geniusthinks.Enough material has survived from his artworks and notebooks to give us a picture ofLeonardo as almost the singular embodiment of theRenaissance. His mastery of disciplines as diverseas painting, anatomy, engineering, and music werecelebrated in his lifetime and have been the subjectof fascination ever since. He called himself“unlettered” yet commanded the knowledge of themajor scholarly works of the time, and anticipated along list of later discoveries, especially in hismechanical inventions.Here are someof the thingsyou andyour studentswill experience:T Learn about the importance of books andlibraries as repositories of knowledge, historyand cultureT Learn how science and math can be used tomake great artT Learn about Renaissance Italy – its customsand costume, Lorenzo di Medici and otherresidents of Florence, songs, and danceT Discover the world of Leonardo’s Notebooksand learn how he observed, collected, anddocumented his observationsT Find out the value of learning you do on yourown(Appropriate for students ages 7-18)Meet Leonardo da VinciBorn in Vinci (his name means “Leonardo ofthe town Vinci”) in 1452, Leonardo spent his earlylife in the small town living with hisuncle, exploring the countryside andrecording his observations assketches. Because he was born outof wedlock, most opportunities forformal education and manyprofessions were closed to him. Hewas taught basic skills – reading,writing, using an abacus – by apriest.H is father arranged forLeonardo to join him in Florence(“Firenze” in Italian) and apprenticein the prominent painting andsculpting studio of Andrea del Verrocchio in 1467.It was then common for boys of 12 or 13 to learnbusiness or technical occupations as apprentices.His work as a servant in the studio was in exchangefor instruction and training in all aspects of thework of Verrochio’s studio. As garzone, orstudio boy, Leonardo learned togrind pigment to make paint,prepare painting surfaces, makepaint brushes and polish bronzesculpture. At the end of his sixyear apprenticeship, Leonardo wasadmitted to the Florentinepainters’ guild as maestro ormaster, but stayed on withVerrochio until 1482.I t was in Verrochio’s studiothat Leonardo began to usescience and mathematics toimprove his art. He helpeddevelop techniques for mixing andusing oil paint, which had only recently beenintroduced in Italy. He also discovered a way tocreate the illusion of three-dimensionality in hisPage 1 of 6

paintings by using geometry. Several Renaissancescholars had developed theories of perspective, thepresentation of three-dimensional objects on a twodimensional surface, but Leonardo improved uponexisting theories by Brunelleschi and Alberti, andhis paintings became study pieces for the artists ofhis day. His scientific approach to art was in partan effort to persuade others that painting should beconsidered at the level of the liberal arts, i.e.rhetoric, philosophy, mathematics, poetry, etc.What is more scientific,he reasoned, than being able to see and to projectwhat one sees onto a flat surface?A s Leonardo moved from Milan, to Venice,and finally France, he used his ability as an artistand inventor to gain access to the highest levelsof power and wealth. His ability to cultivatewealthy and influential patrons of his work was akey factor in his remarkable career.Renaissance ItalyThe Renaissance, or rebirth, ofEurope beginning in the 15th century was atime of great opportunity and achievementin culture, exploration, and theaccessibility of knowledge. In Italy,wealthy ruling families such as the Mediciscommissioned great works of art andarchitecture. Masterpieces like the SistineChapel remind us today of the greatachievements of this time. Explorers suchas Columbus and Magellan set out onvoyages to lands and cultures unknown toEuropeans at that time. They established contactand trade with cultures across the globe and madean unprecedented variety of goods from India,central Asia, and the Far East available.Prior to the advent of the printing press in thelate Middle Ages, books were hand-written bymonks, one at a time. Information and knowledgewas available only to those who had the wealth toobtain monastic manuscripts. Printed books were acrucial catalyst for the Renaissance, resulting in thepublication and dissemination of classical texts andworks by contemporary authors. Each successivegeneration grew increasingly literate due to thespeed and availability of knowledge. Use of thevernacular languages (as opposed to Latin)increased, resulting in more books that could beread by literate, and not only learned people.share information also provided an opportunityfor rebuttal and exchange of ideas. Leonardocarefully analyzed the approximately 116 bookshe owned andrecorded hisresponse anddisagreements withthem in hisnotebooks. ForLeonardo, the mostreliable source ofknowledge was hisown observation.Scientific knowledge became accessible tomany more people through books; this ability toPage 2 of 6

The Gutenberg BibleDon’t miss the opportunity to see the Libraryof Congress’ edition of the Gutenberg Bible.Printed in 1456, it is one of only 48 copies of theoriginal in existence, and one of only three perfectcopies printed on vellum. This Bible is the firstincunabula – a book printed before 1501 – printedwith moveable type. Leonardo da Vinci collectedbooks for his own library like anotherRenaissance man, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’sbooks became the foundation for the Library ofCongress’ Rare Book collection, but since itsfounding, the Library has collected nearly 5,700fifteenth-century books and incunabula – thelargest collection in the western hemisphere.Copies of many of the books Leonardo ownedare also in the Library of Congress’ collection.Suggested pre activitiesGutenberg and the Printing PressThe creation and use of moveable type to print books, first developed by Johannes Gutenberg in1456, is the single most important factor in the widespread availability and dissemination of knowledgeduring the Renaissance. Information became available to many more people, and theories and ideas couldbe developed through the interaction that books enabled. Even though Leonardo da Vinci could notattend the university, the works of the most important scholars of his time were available to him throughbooks. You can help students understand the significance of Gutenberg’s invention by having themresearch his life and career on the web and reporting their findings on a time line, or by writing a report.A lesson plan on this topic is available at:http://www.educationworld.com/a lesson/00-2/1p2178.shtmlSuggested post activitiesRecent books:Leonardo’s Laptop (Ben Schneiderman, MITPress, 2003) and How to Think Like Leonardo daVinci: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day(Michael J. Gelb, Dell Books, 2000) areexamples of the continued interest in Leonardoda Vinci’s work.Page 3 of 6

Try these activitiesMeasure like LeonardoVitruvian Man: Leonardo da Vinci based his famous drawingon a description by the Roman engineer Vitruvius of theproportions of the human body. Determining ratio andproportion was an extremely important activity in theRenaissance-era because there was no standard monetary unitor standard system of weights and measures. People frequentlyencountered the need to estimate the size or value of somethingby comparing it to something else.You can help students understand this principle by having themmeasure each section of their arms and legs with a string, stick,piece of paper, etc. and comparing the measurements. Askstudents: Why do you think we call a unit of measurement 12inches long a foot? How long is your foot compared to thelength of your leg? How many hands long is your arm?A lesson plan using the Vitruvian Man is available nardo.htmlDraw like LeonardoGeometric shapes: Leonardo da Vinci becamefascinated with geometry and mathematicsthrough his friendship and collaboration withFra Luca Pacioli. You can help students learnmore about basic geometric shapes by helpingthem learn to describe their qualities.Ask them: What makes a square different froma circle? How many sides does a triangle have?How many points or corners? Have studentswork with shapes by creating tangrams; moreadvanced students can create three-dimensionalshapes like da Vinci’s illustrations for Pacioli’sbook, Summa.A lesson plan on this topic is available ap4/4.4/index.htmPage 4 of 6

Play like LeonardoLeonardo da Vinci invented set devices for the theater and even designed sets forseveral productions. Some of the ideas he recorded in his notebook concern how tomake costumes or to light sets. Theatrical productions in Leonardo’s day frequentlymade use of masks to identify characters the members of the audience wouldrecognize. Much like today’s sitcoms make use of stock characters such as the dumbjock, the geek, the snotty rich girl, etc. the Commedia’s characters were equally wellknown. They were identified in the productions by costume, mask, and mannerisms.The following site has more information about the Commedia, as well as instructionsfor making a papier mache mask:http://consorte bella e like LeonardoLeonardo valued his own observation above anything he read in a book.He wrote that his writingswould be based on a “much greater and much more noble” authority than any written description. Infact, he frequently challenged the current knowledge of the time. For example, Leonardo did not acceptthe common belief that the moon had its own source of light. Through observation, he concludedcorrectly that the sun’s reflection lights the moon. He also observed the moon formany days and noticed that the phases of the moon occurred regularly. Herecorded his findings in his notebooks and drew the phenomena of earthshine,when the unlit portion of the moon is still visible in the night sky. Leonardo’semphasis on experience is a critical element in the development of the scientifictheory. His notebooks contain examples of experiments he conducted again andagain by just changing one variable.Encourage students to observe the moon. They can keep a journal and sketch themoon at the same time each night, noting its location and phase; or they can create achart to track their observations.A description and activity on the phases of the moon is available ons/tnl/12/12.htmlAn introduction to the Scientific Method is available at:http://teacher.nsrl.rochester.edu/phy labs/AppendixE/AppendixE.htmlWrite like LeonardoLeonardo was left-handed and wrote backwards in his notebooks fromright to left. Try it yourself! Write your name or a word on one line, thentry to write it backwards on the next ttoLeft.htmlPage 5 of 6

BooksMichael J. Gelb, How to Think Like Leonardo: Seven Steps to Genius Every Day. New York, NY: Delacorte Press,1998.Janis Herbert, Leonardo da Vinci for Kids: His Life and Ideas: 21 Activities. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1998.(A lively biography for grade 4 and up.)Andrew Langley, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. Philadelphia, Pa.: Running Press, 2001. (Grade 4-6)Fiona Macdonald, The World in the Time of Leonardo da Vinci. Parsippany, N.J. : Dillon Press, 1998. (Ages 9-12)Richard McLanathan. Leonardo Da Vinci (An Abrams First Impressions Book). Abrams Books for Young Readers,1990. A fresh, detailed introduction to Leonardo’s art and science, with great explanations and superb qualityreproductions. (Gr. 5–12)Irma A. Richter, ed., The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1998.(Comprehensive guide to Leonardo’s drawings and writings.)Stewart Ross, Leonardo da Vinci.(Scientists Who Made History Series). Austin, TX : Raintree Steck-Vaughn, 2002.(Ages 9-12)Peggy Saari & Aaron Saari, eds.; Julie Carnagie, project ed., Renaissance & Reformation, Primary Sources. Detroit :UXL, 2002.Ben Schneiderman, Leonardo’s Laptop: Human Needs and the New Computing Technologies. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press, 2002.Diane Stanley, Leonardo da Vinci. HarperCollins, 1996. (Excellent introduction by one of the best children’sbiographers. Grade 2 and up.)MediaThe Cradle of the Renaissance: Italian Music for the Time of Leonardo da Vinci. London: Hyperion, 1995.Web sitesLeonardo da Vinci: the Man & the o’s Workshop: Renaissance leonardo/index.htmlLeonardo @ the Museum: Virtual Leonardohttp://www.mos.org/leonardo/Inventor’s Workshop: Leonardo’s rams/invention-leonardoslegacy/Leonardo da Vinci, National Museum of Science and Technology, Virtual .us/Renaissance/VirtualRen.htmlLeonardo Museum in Vincihttp://www.leonet.it/comuni/vinci/Page 6 of 6

The life and works of artist and scientist Leonardo da Vinci continue to fascinate us because, while he exemplified the Italian . anatomy, engineering, and music were . incunabula – a book printed before 1501 – printed with mo