Transcription

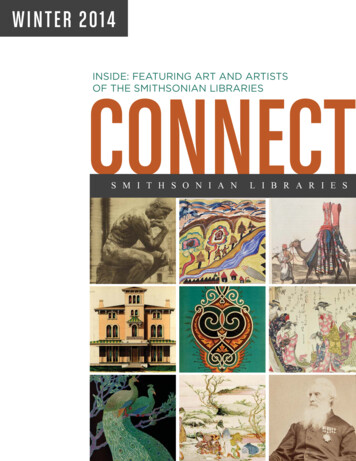

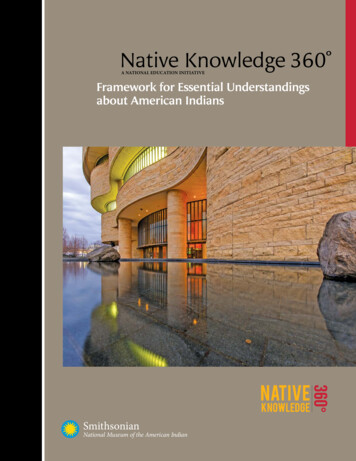

Native Knowledge 360 A NATIONAL EDUCATION INITIATIVE Framework for Essential Understandingsabout American IndiansSmithsonianNational Museum of the American Indian

NATIVE KNOWLEDGE 360 A National Education InitiativeTransforming Teaching and Learningabout American IndiansThe Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is joining with Nativecommunities and educators nationally to help change the way American Indian histories, cultures, andcontemporary lives are taught in K-12 classrooms. This long-term initiative, Native Knowledge 360 (NK360 ), provides educators and students with deeper and more comprehensive knowledge andperspectives about Native Peoples, bringing the richness of the museum’s collections, scholarship, andlive programming, along with the diverse voices of Native experts and young people, directly intoclassrooms nationwide. At the center of Native Knowledge 360 are Native people themselves.Currently, there is little evidence in classroom materials—textbooks, curricula, or academicstandards—of important historical and contemporary events that include American Indian knowledgeand perspectives, and little or no integration of these events into the larger narratives of American andworld history. The museum’s collaborations with Native communities, teachers, scholars, andeducational leaders are essential to the development of new resources for the classroom. NativeKnowledge 360 is a platform for NMAI and Native Peoples to correct, broaden, and improve what istaught in the nation’s schools and to provide model instructional materials and professionaldevelopment for teachers. It also serves as a stimulus for the national conversation on education forand about American Indians. To anchor this work, the Native Knowledge 360 home page featuressearchable lessons and resources for the classroom, information about programs and professionaldevelopment opportunities for educators, and additional information about the NK360 initiative.Visit AmericanIndian.si.edu/nk360.Volkswagen Beetle named “Vochol,” decoratedby Huichol (Wixaritari) artists using morethan 2 million glass beads, 2006. Photographby Alejandro Piedra Buena, courtesy of theMuseo de Arte PopularWorking in collaboration with Native communities, education agencies and organizations, scholars,and teachers, the NMAI has developed classroom-ready resources that are diverse in content andformat. Digital inquiry lessons, interactives, teaching posters, educational websites, and videos helpteachers and students understand the complex and robust stories of Native America. Classroomresources feature primary and secondary sources, Native perspectives, images, and objects from themuseum’s collection. Materials are accompanied by lesson plans for teachers and skills-basedassessments for students. NK360 materials are designed to align with relevant standards, such as theCommon Core State Standards (CCSS); the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for socialstudies education; and STEM and arts-related standards. With these classroom resources, teachers cantrust that they are providing their students with accurate, vetted, and culturally appropriate materials.In addition, the NMAI offers engaging professional-development programs for teachers in a variety offormats, such as residencies, institutes, workshops, digital learning, and conference presentations.Native Knowledge 360 resources and teacher training empower educators to confidently buildmeaningful classroom experiences that provide a more complete understanding of Native Americanhistories, cultures, and contemporary lives.1

Educators! The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) invites you toconsider content about American Indians from a more complete perspective. NMAI’s NativeKnowledge 360 (NK360 ): Essential Understandings about American Indians is a framework thatallows you to see new possibilities for creating student learning experiences. Building on the tenthemes of the National Council for the Social Studies’ national curriculum standards, NMAI’sEssential Understandings reveal key concepts about the rich and diverse cultures, histories, andcontemporary lives of Native Peoples. These concepts reflect a multitude of untold stories aboutAmerican Indians that can deepen and expand your teaching of history, geography, civics, economics,science, engineering, and other subject areas.NMAI collaborated with Native communities, national and state education agencies, educators, andothers to develop these Essential Understandings. They serve as the foundation for our museum’seducational work. We also share them with teachers, curriculum developers, other museums, state andfederal agencies, and education organizations to promote more expansive and informed thinkingabout Native American histories, cultures, and contemporary lives. We encourage state and localeducators to work with Native Peoples in their areas to make the Essential Understandings morespecific and relevant to their regions and to design curricula and materials that address localstandards.Teachers know that it is impossible to teach about the Americas—histories, governments, cultures,environments, societies, and contemporary issues—without teaching about Native Americans. Insteadof the same old lessons about ancient American Indian food, clothing, and shelter, we invite you toexplore the resources available to educators through NK360 . Visit AmericanIndian.si.edu/nk360 andconsider how you can expand your students’ knowledge and understanding of the contributions andexperiences of Native Peoples of the Western Hemisphere. Resources from Native Knowledge 360 demonstrate what NMAI’s Essential Understandings look like in action.Special acknowledgement: The NMAI thanks the Montana and South Dakota Offices of Indian Education, who firstestablished Essential Understandings for their respective states and have partnered with the NMAI to create itsnational framework.2N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sFramework for Essential Understandingsabout American IndiansN ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNATIVE KNOWLEDGE 360 A National Education InitiativeNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDING1AMERICAN INDIAN CULTURESThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of American Indiancultures and cultural diversity.Culture is a result of human socialization. People acquire knowledge and values by interacting with otherpeople through common language, place, and community. In the Americas, there is vast cultural diversityamong more than 2,000 tribal groups. Tribes have unique cultures and ways of life that span history fromtime immemorial to the present day.KEY CONCEPTSThere is no single American Indian cultureor language.American Indian cultures have always beendynamic and changing.American Indians are both individuals andmembers of a tribal group.Interactions with Europeans and Americansbrought accelerated and often devastatingchanges to American Indian cultures.For millennia, American Indians have shapedand been shaped by their culture andenvironment. Elders in each generation teachthe next generation their values, traditions,and beliefs through their own tribal languages,social practices, arts, music, ceremonies,and customs.Kinship and extended family relationshipshave always been and continue to be essentialin the shaping of American Indian cultures.Native people continue to fight to maintainthe integrity and viability of indigenoussocieties. American Indian history is one ofcultural persistence, creative adaptation,renewal, and resilience.American Indians share many similarities withother indigenous people of the world, alongwith many differences.(Left to right)O-o-be (Kiowa), 1895.Fort Sill, Oklahoma.Photographer unknown, NMAI.Kwagiulth Flower by RichardHunt (Kwak’waka’wakw),2006.Photograph by RogerWhiteside, NMAI.Christopher Cote (Osage),2008. Skiatook, Oklahoma.Photograph by KatherineFogden (Mohawk), NMAI3

TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGEThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of AmericanIndian history and its legacy.Indigenous people of the Americas shaped life in the Western Hemisphere for millennia. After contact,American Indians and the events involving them greatly influenced the histories of the European coloniesand the modern nations of North, Central, and South America. Today, this influence continues to playsignificant roles in many aspects of political, legal, cultural, environmental, and economic issues. Tounderstand the history and cultures of the Americas requires understanding American Indian historyfrom Indian perspectives.KEY CONCEPTSMany American Indian communities havecreation stories that specify their origins in theWestern Hemisphere.Indigenous people played a significant role inthe history of the Americas. Many of thesehistorically important events and developmentsin the Americas shaped the modern world.American Indians have lived in the WesternHemisphere for at least 15,000–20,000 years.The Western Hemisphere was laced withdiverse, well-developed, and complex societiesthat interacted with one another over millennia.Providing an American Indian context tohistory makes for a greater understanding ofworld history.American Indian history is not singular ortimeless. American Indian cultures have alwaysadapted and changed in response toenvironmental, economic, social, and otherfactors. American Indian cultures and people arefully engaged in the modern world.N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n s2N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDING3PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTSThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of American Indianpeople, places, and environments.For thousands of years, indigenous people have studied, managed, honored, and thrived in theirhomelands. These foundations continue to influence American Indian relationships and interactionswith the land today.KEY CONCEPTSThe story of American Indians in the WesternHemisphere is intricately intertwined withplaces and environments. Native knowledgesystems resulted from long-term occupationof tribal homelands, and observation andinteraction with places. American Indiansunderstood and valued the relationshipbetween local environments and culturaltraditions, and recognized that human beingsare part of the environment.Throughout their histories, Native groupshave relocated and successfully adapted to newplaces and environments.Long before their contact with Europeans,indigenous people populated the Americasand were successful stewards and managers ofthe land, from the Arctic Circle to Tierra delFuego. European contact resulted in exposureto Old World diseases, displacement, and wars,devastating the underlying foundations ofAmerican Indian societies.The imposition of international, state,reservation, and other borders on Native landschanged relationships between people andtheir environments, affected how people lived,and sometimes isolated tribal citizens andfamily members from one another.Well-developed systems of trails, includingsome hard-surfaced roads, interlaced theWestern Hemisphere prior to Europeancontact. These trading routes made possiblethe exchange of foods and other goods. Manyof the trails were later used by EuroAmericans as roads and highways.American Indians employed a variety ofmethods to record and preserve their histories.European contact resulted in devastating loss oflife, disruption of tradition, and enormous lossof lands for American Indians.Hearing and understanding American Indianhistory from Indian perspectives provides animportant point of view to the discussion ofhistory and cultures in the Americas. Indianperspectives expand the social, political, andeconomic dialogue.4Young powwowdancer, 2007.Photograph by CynthiaFrankenburg, NMAI(Left to right) Saguaroand prickly pear cactuseson the Sonoran Desert,2004. Photograph byRoger Whiteside, NMAIWild rice harvesting, 2010.Leech Lake, Minnesota.Photograph by KatCommunications, NMAI.5

INDIVIDUAL DEVELOPMENT AND IDENTITYThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of individualdevelopment and identity among American Indians.American Indian individual development and identity is tied to culture and the forces that haveinfluenced and changed culture over time. Unique social structures, such as clan systems, rites of passage,and protocols for nurturing and developing individual roles in tribal society, characterize each AmericanIndian culture. American Indian cultures have always been dynamic and adaptive in response tointeractions with others.KEY CONCEPTSFor American Indians, identity developmenttakes place in a cultural context, and theprocess differs from one American Indianculture to another. American Indian identityis shaped by the family, peers, social norms,and institutions inside and outside acommunity or culture.Historically, well-established conventionsand practices nurtured and promoted thedevelopment of individual identity. Theseincluded careful observation and nurturingof individual talents and interests by eldersand family members; rites of passage; socialand gender roles; and family specializations,such as healers, religious leaders, artists,and whalers.Contact with Europeans and Americansdisrupted and transformed traditional normsfor identity development.Today, Native identity is shaped by manycomplex social, political, historical, andcultural factors.In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, manyAmerican Indian communities have soughtto revitalize and reclaim their languagesand cultures.Lummi Nation First SalmonCeremony, 2010. Photograph byKat Communications, NMAI6N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n s4N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDING5INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONSThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of interactionsamong American Indian individuals, groups, and institutions, and with those of other cultures andsocieties as well.American Indians have always operated and interacted within self-defined social structures that includeinstitutions, societies, and organizations, each with specific functions. These social structures have shapedthe lives and histories of American Indians through the present day.KEY CONCEPTSAmerican Indian institutions, societies, andorganizations defined people’s relationshipsand roles, and managed responsibilities inevery aspect of life—religion, health,government, diplomacy, war, agriculture,hunting and fishing, trade, and so on.Native kinship systems were influential inshaping people’s roles and interactions amongother individuals, groups, and institutions.External educational, governmental, andreligious institutions have exerted majorinfluences on American Indian individuals,groups, and institutions. Native people havefought to counter these pressures and haveadapted to them when necessary. Many Nativeinstitutions today are mixtures of Native andWestern constructs, reflecting externalinfluence and Native adaptation.A variety of specialized agencies have beenformed to interact with and serve AmericanIndian individuals, groups, and institutions.Today, because of treaties, court decisions, andstatutes, tribal governments maintain a uniquerelationship with federal and stategovernments.Today, American Indian governments upholdtribal sovereignty and promote tribal cultureand well-being.Navajo Code Talkers in World WarII, 1943. Bougainville Island,Papua New Guinea. Photograph byUnited States Marine Corps,courtesy of National Archives7

POWER, AUTHORITY, AND GOVERNANCEThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of how AmericanIndians create, interact with, and change structures of power, authority, and governance.American Indians devised and have always lived under a variety of complex systems of government.Tribal governments faced rapid and devastating change as a result of European colonization and thedevelopment of the United States. Tribes today still govern their own affairs and maintain agovernment-to-government relationship with the United States and other governments.KEY CONCEPTSToday, tribal governments operate underself-chosen traditional or constitution-basedgovernmental structures. Based on treaties, laws,and court decisions, they operate as sovereignnations within the United States, enacting andenforcing laws and managing judicial systems,social well-being, natural resources, andeconomic, educational, and other programs fortheir members. Tribal governments are alsoresponsible for interactions with Americanfederal, state, and municipal governments.Long before European colonization, AmericanIndians had developed a variety of complexsystems of government that embodiedimportant principles for effective rule.American Indian governments and leadersinteracted, recognized each other’s sovereignty,practiced diplomacy, built strategic alliances,waged wars, and negotiated peace accords.debate. Many of these policies had a devastatingeffect on established American Indian governingprinciples and systems. Other policies sought tostrengthen and restore tribal self-government.A variety of historical policy periods have had amajor impact on American Indian people’sabilities to self-govern. These include:- Colonization Period, since 1492- Treaty Period, 1789–1871- Removal Period, 1834–1871- Allotment/Assimilation Period, 1887–1934- Tribal Reorganization, 1934–1958- Termination, 1953–1988- Self-Determination, 1975–present8NMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDING7PRODUCTION, DISTRIBUTION,AND CONSUMPTIONThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of how AmericanIndian people organize for the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, bothin the past and today.American Indians developed a variety of economic systems that reflected their cultures and managed theirrelationships with others. Prior to European arrival in the Americas, American Indians produced andtraded goods and technologies using well-developed systems of trails and widespread transcontinental,intertribal trade routes. Today, American Indian tribes and individuals are active in economic enterprisesthat involve production and distribution.KEY CONCEPTSFor thousands of years American Indiansdeveloped and operated vast trade networksthroughout the Western Hemisphere.American Indians traded, exchanged,gifted, and negotiated the purchase ofgoods, foods, technologies, domesticanimals, ideas, and cultural practiceswith one another.American Indians played influentialand powerful roles in trade and exchangeeconomies with partners in Europe duringthe colonial period. These activities alsosupported the development and growth ofthe United States.Today, American Indians are involved ina variety of economic enterprises, seteconomic policies for their nations, andown and manage natural resources thataffect the production, distribution, andconsumption of goods and servicesthroughout much of the United States.After 1492, American Indians suffered diseasesand genocidal events that resulted in death on acatastrophic scale and the rapid decimation ofNative populations. These episodes greatlycompromised the continuity of existing tribalgovernment structures.A variety of political, economic, legal, military,and social policies were used by Europeansand Americans to remove and relocateAmerican Indians and to destroy theircultures. U.S. policies regarding AmericanIndians were the result of major nationalN ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n s6N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGUnited States SenatorBen NighthorseCampbell (NorthernCheyenne), 2005.Photograph by WalterLarrimore, NMAINorth American Indian TradeRoutes. Map by CartographicConcepts, Inc., NMAI9

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETYThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of the developmentof Native knowledge and the relationships among science, technology, and society in historical andcontemporary American Indian communities.American Indian knowledge resides in languages, cultural practices, and teaching that spans many generations. This knowledge is based on long-term observation, experimentation, and experience with the livingearth. Indigenous knowledge has sustained American Indian cultures for thousands of years. When appliedto contemporary global challenges, Native knowledge contributes to dynamic and innovative solutions.KEY CONCEPTSAmerican Indian knowledge can informthe ongoing search for new solutions tocontemporary issues.American Indian knowledge and relatedinnovations, goods, and technologies (e.g.,agriculture) have had enormous global impact.American Indian knowledge reflects arelationship developed over millennia withthe living earth based on keen observation,experimentation, and practice.Major social, cultural, and economic changestook place in American Indian cultures as aresult of the acquisition of goods andtechnologies from Europeans and others.American Indian knowledge is closely tied tolanguages, cultural values, and practices. It isfounded on the recognition of the relationshipsbetween humans and the world around them.Much American Indian knowledge was destroyedin the years after contact with Europeans.Nevertheless, the intergenerational transfer oftraditional knowledge, the recovery of culturalpractices, and the creation of new knowledgecontinue in American Indian communities today.American Indian knowledge allowed AmericanIndians to live productive, innovative, andsustainable lives in the diverse environmentsof the Western Hemisphere.(Left to right)Machu Picchufrom the southernagricultural terraces,2011. IRP (Inka RoadProject) Archive, NMAIQueshuar Chakasuspension bridge overthe Apurimac Riverin Peru, 2011. IRP(Inka Road Project)Archive, NMAI10N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n s8N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDING9GLOBAL CONNECTIONSThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of American Indianparticipation in and influences on global connections and interdependence.American Indians have always engaged in the world beyond the immediacy of their own communities.For millennia, indigenous people of North America exchanged and traded ideas, goods, technologies, andarts with other tribal nations, near and far. Global connections expanded and intensified after contactwith Europeans. American Indian foods, technologies, wealth, and labor contributed to the developmentof the modern world.KEY CONCEPTSInteractions among American Indian communities across the Americas contributed to thechange, growth, and vitality of Native nations.Global interactions with Europeans and othershad both positive and negative consequencesfor American Indians.The knowledge and perspectives of AmericanIndians and other indigenous people aroundthe world have the potential to informsolutions as global interdependence intensifiesand change accelerates.As sovereign independent nations, AmericanIndian tribes and their citizens areparticipants in global politics, economies, andother facets of contemporary life.Guatemalan corn.Photograph by KatherineFogden, NMAI11

10CIVIC IDEALS AND PRACTICESThe 21st–century classroom should include experiences that provide for the study of the ideals,principles, and practices of citizenship in American Indian societies past and present.Ideals, principles, and practices of citizenship have always been part of American Indian societies. Therights and responsibilities of American Indian individuals have been defined by the values, morals, andbeliefs common to their cultures. American Indians today may be citizens of their tribal nations, thestates they live in, and the United States.KEY CONCEPTSAs citizens of their tribal nations, AmericanIndians have always had certain rights,privileges, and responsibilities that are tied tocultural values and beliefs and thus vary fromculture to culture.As U.S. citizens, American Indians have oftenbeen denied the same rights and privileges asother U.S. citizens. They have formedmovements to gain equitable rights andprivileges.Not all American Indians today are citizensof their tribes.More than 560 tribal governments arerecognized by the United States as havingrights of sovereign self-government. Dozens ofother tribes are recognized by various stategovernments, whose authorities andresponsibilities differ according to the laws ofthe states.American Indians have acquired U.S.citizenship through a variety of means,including certain treaties and military service.Citizenship for all American Indians did notoccur until the passage of the IndianCitizenship Act of 1924.N ati v e Kn o w le dge 3 6 0 : F r am e wo r k f o r E s s e n ti a l U n d e rs ta n d i n gs a bo u t A me ri c a n I n d i a n sNMAI ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGVisit our website:AmericanIndian.si.edu/nk360Some American Indian people have neitherdesired nor accepted U.S. citizenship.American Indians today may becitizens of their tribes, the UnitedStates, and the states in which they live.Maya ceremony, 2011. Photograph by Isabel Hawkins, NMAI(Background photograph) Maya corn, 2011. Photograph by Isabel Hawkins, NMAIPresident Calvin Coolidge withNative delegation, 1925.Photograph courtesy of theLibrary of Congress12

Front cover: The National Museum of the AmericanIndian, 2013. Photograph by Digital Blue, RussCoover. NMAIBack cover: Buffalo Boy and His Duesenbird by Jesse T.Hummingbird (Oklahoma Cherokee), ca.2000-2004. Gift of R.E. Mansfield. NMAISmithsonianNational Museum of the American IndianPO BOX 37012MRC 590WASHINGTON, DC 20013-7012

educational leaders are essential to the development of new resources for the classroom. Native Knowledge 360 is a platform for NMAI and Native Peoples to correct, broaden, and improve what is taught in the nation’s schools and to provide model instructional materials an