Transcription

FAA-H-8083-15AInstrumentFlying HandbookU.S. Departmentof TransportationFEDERAL AVIATIONADMINISTRATION

Instrument FlyingHandbook2007U.S. Department of TransportationFEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATIONFlight Standards Service

ii

PrefaceThis Instrument Flying Handbook is designed for use by instrument flight instructors and pilots preparing for instrumentrating tests. Instructors may find this handbook a valuable training aid as it includes basic reference material for knowledgetesting and instrument flight training. Other Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) publications should be consulted formore detailed information on related topics.This handbook conforms to pilot training and certification concepts established by the FAA. There are different ways ofteaching, as well as performing, flight procedures and maneuvers and many variations in the explanations of aerodynamictheories and principles. This handbook adopts selected methods and concepts for instrument flying. The discussion andexplanations reflect the most commonly used practices and principles. Occasionally the word “must” or similar languageis used where the desired action is deemed critical. The use of such language is not intended to add to, interpret, or relievea duty imposed by Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR).All of the aeronautical knowledge and skills required to operate in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) are detailed.Chapters are dedicated to human and aerodynamic factors affecting instrument flight, the flight instruments, attitude instrumentflying for airplanes, basic flight maneuvers used in IMC, attitude instrument flying for helicopters, navigation systems, theNational Airspace System (NAS), the air traffic control (ATC) system, instrument flight rules (IFR) flight procedures, andIFR emergencies. Clearance shorthand and an integrated instrument lesson guide are also included.This handbook supersedes FAA-H-8081-15, Instrument Flying Handbook, dated 2001.This handbook may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office (GPO),Washington, DC 20402-9325, or from GPO's web site.http://bookstore.gpo.govThis handbook is also available for download, in PDF format, from the Regulatory Support Division's (AFS-600) website.http://www.faa.gov/about/office org/headquarters offices/avs/offices/afs/afs600This handbook is published by the United States Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, AirmanTesting Standards Branch, AFS-630, P.O. Box 25082, Oklahoma City, OK 73125.Comments regarding this publication should be sent, in email form, to the following address.AFS630comments@faa.goviii

iv

AcknowledgementsThis handbook was produced as a combined Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and industry effort. The FAA wishesto acknowledge the following contributors:The laboratory of Dale Purves, M.D. and Mr. Al Seckel in providing imagery (found in Chapter 1) for visual illusionsfrom the book, The Great Book of Optical Illusions, Firefly Books, 2004Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation and Robinson Helicopter Company for imagery provided in Chapter 9Garmin Ltd. for providing flight system information and multiple display systems to include integrated flight, GPS andcommunication systems; information and hardware used with WAAS, LAAS; and information concerning encounteringemergencies with high-technology systemsUniversal Avionics System Corporation for providing background information of the Flight Management System andan overview on Vision–1 and Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance systems (TCAS)Meggitt/S-Tec for providing detailed autopilot information regarding installation and useCessna Aircraft Company in providing instrument panel layout support and information on the use of onboard systemsKearfott Guidance and Navigation Corporation in providing background information on the Ring-LASAR gyroscopeand its historyHoneywell International Inc., for Terrain Awareness Systems (TAWS) and various communication and radio systemssold under the Bendix-King nameChelton Flight Systems and Century Flight Systems, Inc., for providing autopilot information relating to Highway inthe Sky (Chelton) and HSI displays (Century)Avidyne Corporation for providing displays with alert systems developed and sold by Ryan International, L3Communications, and Tectronics.Additional appreciation is extended to the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the AOPA Air Safety Foundation,and the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) for their technical support and input.v

vi

IntroductionIs an Instrument Rating Necessary?The answer to this question depends entirely upon individualneeds. Pilots may not need an instrument rating if they fly infamiliar uncongested areas, stay continually alert to weatherdevelopments, and accept an alternative to their original plan.However, some cross-country destinations may take a pilotto unfamiliar airports and/or through high activity areas inmarginal visual or instrument meteorological conditions(IMC). Under these conditions, an instrument rating maybe an alternative to rerouting, rescheduling, or cancelinga flight. Many accidents are the result of pilots who lackthe necessary skills or equipment to fly in marginal visualmeteorological conditions (VMC) or IMC and attempt flightwithout outside references.Pilots originally flew aircraft strictly by sight, sound, andfeel while comparing the aircraft’s attitude to the naturalhorizon. As aircraft performance increased, pilots requiredmore inflight information to enhance the safe operation oftheir aircraft. This information has ranged from a string tiedto a wing strut, to development of sophisticated electronicflight information systems (EFIS) and flight managementsystems (FMS). Interpretation of the instruments and aircraftcontrol have advanced from the “one, two, three” or “needle,ball, and airspeed” system to the use of “attitude instrumentflying” techniques.Navigation began by using ground references with deadreckoning and has led to the development of electronicnavigation systems. These include the automatic directionfinder (ADF), very-high frequency omnidirectional range(VOR), distance measuring equipment (DME), tactical airnavigation (TACAN), long range navigation (LORAN),global positioning system (GPS), instrument landing system(ILS), microwave landing system (MLS), and inertialnavigation system (INS).Perhaps you want an instrument rating for the same basicreason you learned to fly in the first place—because you likeflying. Maintaining and extending your proficiency, once youhave the rating, means less reliance on chance and more onskill and knowledge. Earn the rating—not because you mightneed it sometime, but because it represents achievement andprovides training you will use continually and build uponas long as you fly. But most importantly it means greatersafety in flying.Instrument Rating RequirementsA private or commercial pilot must have an instrumentrating and meet the appropriate currency requirements ifthat pilot operates an aircraft using an instrument flightrules (IFR) flight plan in conditions less than the minimumsprescribed for visual flight rules (VFR), or in any flight inClass A airspace.You will need to carefully review the aeronautical knowledgeand experience requirements for the instrument rating asoutlined in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations(14 CFR) part 61. After completing the Federal AviationAdministration (FAA) Knowledge Test issued for theinstrument rating, and all the experience requirements havebeen satisfied, you are eligible to take the practical test. Theregulations specify minimum total and pilot-in-commandtime requirements. This minimum applies to all applicantsregardless of ability or previous aviation experience.Training for the Instrument RatingA person who wishes to add the instrument rating to his orher pilot certificate must first make commitments of time,money, and quality of training. There are many combinationsof training methods available. Independent studies may beadequate preparation to pass the required FAA KnowledgeTest for the instrument rating. Occasional periods of groundand flight instruction may provide the skills necessary topass the required test. Or, individuals may choose a trainingfacility that provides comprehensive aviation education andthe training necessary to ensure the pilot will pass all therequired tests and operate safely in the National AirspaceSystem (NAS). The aeronautical knowledge may beadministered by educational institutions, aviation-orientedschools, correspondence courses, and appropriately ratedinstructors. Each person must decide for themselves whichtraining program best meets his or her needs and at the sametime maintain a high quality of training. Interested personsvii

should make inquiries regarding the available training atnearby airports, training facilities, in aviation publications,and through the FAA Flight Standards District Office(FSDO).Although the regulations specify minimum requirements,the amount of instructional time needed is determined notby the regulation, but by the individual’s ability to achievea satisfactory level of proficiency. A professional pilot withdiversified flying experience may easily attain a satisfactorylevel of proficiency in the minimum time required byregulation. Your own time requirements will depend upon avariety of factors, including previous flying experience, rateof learning, basic ability, frequency of flight training, type ofaircraft flown, quality of ground school training, and qualityof flight instruction, to name a few. The total instructionaltime you will need, the scheduling of such time, is up to theindividual most qualified to judge your proficiency—theinstructor who supervises your progress and endorses yourrecord of flight training.You can accelerate and enrich much of your training byinformal study. An increasing number of visual aids andprogrammed instrument courses is available. The best courseis one that includes a well-integrated flight and ground schoolcurriculum. The sequential nature of the learning processrequires that each element of knowledge and skill be learnedand applied in the right manner at the right time.Part of your instrument training may utilize a flight simulator,flight training device, or a personal computer-based aviationtraining device (PCATD). This ground-based flight trainingequipment is a valuable tool for developing your instrumentcross-check and learning procedures, such as intercepting andtracking, holding patterns, and instrument approaches. Oncethese concepts are fully understood, you can then continuewith inflight training and refine these techniques for fulltransference of your new knowledge and skills.Holding the instrument rating does not necessarily make you acompetent all-weather pilot. The rating certifies only that youhave complied with the minimum experience requirements,that you can plan and execute a flight under IFR, that youcan execute basic instrument maneuvers, and that you haveshown acceptable skill and judgment in performing theseactivities. Your instrument rating permits you to fly intoviiiinstrument weather conditions with no previous instrumentweather experience. Your instrument rating is issued onthe assumption that you have the good judgment to avoidsituations beyond your capabilities. The instrument trainingprogram you undertake should help you to develop not onlyessential flying skills but also the judgment necessary to usethe skills within your own limits.Regardless of the method of training selected, the curriculumin Appendix B, Instrument Training Lesson Guide, providesguidance as to the minimum training required for the additionof an instrument rating to a private or commercial pilotcertificate.Maintaining the Instrument RatingOnce you hold the instrument rating, you may not act as pilotin-command under IFR or in weather conditions less than theminimums prescribed for VFR, unless you meet the recentflight experience requirements outlined in 14 CFR part 61.These procedures must be accomplished within the preceding6 months and include six instrument approaches, holdingprocedures, and intercepting and tracking courses through theuse of navigation systems. If you do not meet the experiencerequirements during these 6 months, you have another 6months to meet these minimums. If the requirements arestill not met, you must pass an instrument proficiency check,which is an inflight evaluation by a qualified instrumentflight instructor using tasks outlined in the instrument ratingpractical test standards (PTS).The instrument currency requirements must be accomplishedunder actual or simulated instrument conditions. You may loginstrument flight time during the time for which you controlthe aircraft solely by reference to the instruments. This canbe accomplished by wearing a view-limiting device, such asa hood, flying an approved flight-training device, or flyingin actual IMC.It takes only one harrowing experience to clarify thedistinction between minimum practical knowledge and athorough understanding of how to apply the procedures andtechniques used in instrument flight. Your instrument trainingis never complete; it is adequate when you have absorbedevery foreseeable detail of knowledge and skill to ensure asolution will be available if and when you need it.

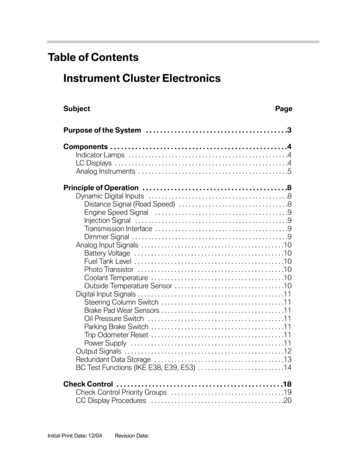

Table of ContentsPreface .iiiAcknowledgements .vIntroduction.viiIs an Instrument Rating Necessary? .viiInstrument Rating Requirements .viiTraining for the Instrument Rating.viiMaintaining the Instrument Rating .viiiTable of Contents .ixChapter 1Human Factors .1-1Introduction .1-1Sensory Systems for Orientation .1-2Eyes .1-2Vision Under Dim and Bright Illumination .1-3Ears .1-4Nerves.1-5Illusions Leading to Spatial Disorientation.1-5Vestibular Illusions .1-5The Leans.1-5Coriolis Illusion .1-6Graveyard Spiral .1-6Somatogravic Illusion .1-6Inversion Illusion .1-6Elevator Illusion.1-6Visual Illusions .1-7False Horizon .1-7Autokinesis .1-7Postural Considerations .1-7Demonstration of Spatial Disorientation .1-7Climbing While Accelerating.1-8Climbing While Turning .1-8Diving While Turning .1-8Tilting to Right or Left .1-8Reversal of Motion .1-8Diving or Rolling Beyond the Vertical Plane .1-8Coping with Spatial Disorientation.1-8Optical Illusions .1-9Runway Width Illusion .1-9Runway and Terrain Slopes Illusion .1-9Featureless Terrain Illusion .1-9Water Refraction .1-9Haze .1-9Fog .1-9Ground Lighting Illusions .1-9How To Prevent Landing Errors Due To OpticalIllusions .1-9Physiological and Psychological Factors .1-11Stress .1-11Medical Factors.1-12Alcohol .1-12Fatigue .1-12Acute Fatigue .1-12Chronic Fatigue .1-13IMSAFE Checklist .1-13Hazard Identification .1-13Situation 1 .1-13Situation 2 .1-13Risk Analysis.1-13Crew Resource Management (CRM) and Single-PilotResource Management (SRM) .1-14Situational Awareness.1-14Flight Deck Resource Management .1-14Human Resources .1-14Equipment .1-14Information Workload .1-14Task Management .1-15Aeronautical Decision-Making (ADM) .1-15The Decision-Making Process .1-16Defining the Problem .1-16Choosing a Course of Action .1-16Implementing the Decision and Evaluatingthe Outcome .1-16Improper Decision-Making Outcomes .1-16Models for Practicing ADM .1-17Perceive, Process, Perform .1-17The DECIDE Model.1-17Hazardous Attitudes and Antidotes .1-18ix

Chapter 2Aerodynamic Factors .2-1Introduction .2-1The Wing .2-2Review of Basic Aerodynamics .2-2The Four Forces .2-2Lift .2-2Weight.2-3Thrust .2-3Drag .2-3Newton’s First Law, the Law of Inertia .2-4Newton’s Second Law, the Law of Momentum .2-4Newton’s Third Law, the Law of Reaction .2-4Atmosphere .2-4Layers of the Atmosphere .2-5International Standard Atmosphere (ISA).2-5Pressure Altitude .2-5Density Altitude .2-5Lift.2-6Pitch/Power Relationship .2-6Drag Curves .2-6Regions of Command .2-7Control Characteristics .2-7Speed Stability.2-7Normal Command .2-7Reversed Command .2-8Trim.2-8Slow-Speed Flight.2-8Small Airplanes .2-9Large Airplanes .2-9Climbs .2-10Acceleration in Cruise Flight .2-10Turns .2-10Rate of Turn .2-10Radius of Turn .2-11Coordination of Rudder and Aileron Controls .2-11Load Factor .2-11Icing .2-12Types of Icing .2-13Structural Icing .2-13Induction Icing .2-13Clear Ice .2-13Rime Ice .2-13Mixed Ice.2-14General Effects of Icing on Airfoils .2-14Piper PA-34-200T (Des Moines, Iowa) .2-15Tailplane Stall Symptoms .2-16Propeller Icing .2-16Effects of Icing on Critical Aircraft Systems .2-16Flight Instruments .2-16Stall Warning Systems .2-16xWindshields .2-16Antenna Icing .2-17Summary .2-17Chapter 3Flight Instruments .3-1Introduction .3-1Pitot/Static Systems .3-2Static Pressure .3-2Blockage Considerations .3-2Indications of Pitot Tube Blockage .3-3Indications from Static Port Blockage .3-3Effects of Flight Conditions.3-3Pitot/Static Instruments .3-3Sensitive Altimeter .3-3Principle of Operation.3-3Altimeter Errors .3-4Cold Weather Altimeter Errors .3-5ICAO Cold Temperature Error Table .3-5Nonstandard Pressure on an Altimeter .3-6Altimeter Enhancements (Encoding) .3-7Reduced Vertical Separation Minimum (RVSM) .3-7Vertical Speed Indicator (VSI) .3-8Dynamic Pressure Type Instruments .3-8Airspeed Indicator (ASI) .3-8Types of Airspeed .3-9Airspeed Color Codes .3-10Magnetism.3-10The Basic Aviation Magnetic Compass .3-11Magnetic Compass Overview .3-11Magnetic Compass Induced Errors .3-12The Vertical Card Magnetic Compass .3-14The Flux Gate Compass System .3-14Remote Indicating Compass.3-15Gyroscopic Systems .3-16Power Sources .3-16Pneumatic Systems .3-16Vacuum Pump Systems .3-17Electrical Systems .3-18Gyroscopic Instruments .3-18Attitude Indicators .3-18Heading Indicators .3-19Turn Indicators .3-20Turn-and-Slip Indicator .3-20Turn Coordinator .3-21Flight Support Systems .3-22Attitude and Heading Reference System (AHRS) .3-22Air Data Computer (ADC) .3-22Analog Pictorial Displays .3-22Horizontal Situation Indicator (HSI) .3-22

Attitude Direction Indicator (ADI) .3-23Flight Director System (FDS) .3-23Integrated Flight Control System .3-24Autopilot Systems .3-24Flight Management Systems (FMS) .3-25Electronic Flight Instrument Systems .3-27Primary Flight Display (PFD).3-27Synthetic Vision .3-27Multi-Function Display (MFD) .3-28Advanced Technology Systems .3-28Automatic Dependent Surveillance—Broadcast (ADS-B) .3-28Safety Systems .3-30Radio Altimeters .3-30Traffic Advisory Systems .3-31Traffic Information System .3-31Traffic Alert Systems .3-31Traffic Avoidance Systems .3-31Terrain Alerting Systems .3-34Required Navigation Instrument System Inspection .3-34Systems Preflight Procedures .3-34Before Engine Start .3-36After Engine Start.3-37Taxiing and Takeoff .3-37Engine Shut Down .3-37Chapter 4, Section IAirplane Attitude Instrument FlyingUsing Analog Instrumentation .4-1Introduction .4-1Learning Methods .4-2Attitude Instrument Flying Using the Control andPerformance Method .4-2Control Instruments .4-2Performance Instruments .4-2Navigation Instruments .4-2Procedural Steps in Using Control andPerformance .4-2Aircraft Control During Instrument Flight .4-3Attitude Instrument Flying Using the Primary andSupporting Method .4-4Pitch Control .4-4Bank Control .4-7Power Control .4-8Trim Control .4-8Airplane Trim .4-8Helicopter Trim .4-10Example of Primary and Support Instruments .4-10Fundamental Skills.4-10Instrument Cross-Check .4-10Common Cross-Check Errors .4-11Instrument Interpretation .4-13Chapter 4, Section IIAirplane Attitude Instrument FlyingUsing an Electronic Flight Display .4-15Introduction .4-15Learning Methods .4-16Control and Performance Method .4-18Control Instruments .4-18Performance Instruments .4-19Navigation Instruments .4-19The Four-Step Process Used to Change Attitude .4-20Establish .4-20Trim .

from the book, The Great Book of Optical Illusions, Firefl y Books, 2004 Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation and Robinson Helicopter Company for imagery provided in Chapter 9 Garmin Ltd. for providing fl