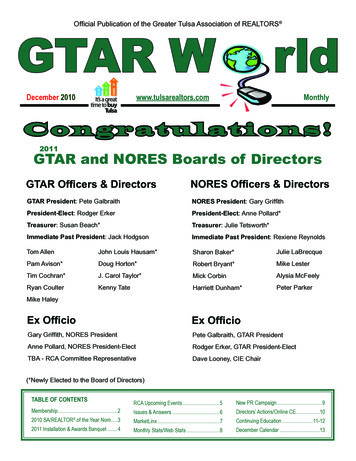

Transcription

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesTeaching Tennessee Williams'sA Streetcar Named DesirefromMultiple Critical PerspectivesEdited byDouglas Grudzina

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireOther titles in the Multiple Critical Perspective series include:A convenient order form is located in the back of this book.1 984Animal FarmAnthemAntigone Awakening, TheBeowulf Brave New WorldCatcher in the Rye, TheComedy of Errors, The Crucible, TheCry, the Beloved CountryDeath of a SalesmanDoll’s House, AEthan FromeFahrenhiet 451FrankensteinGrapes of Wrath, The Great Expectations Great Gatsby, The HamletHeart of DarknessHouse on Mango Street, TheI Know Why the Caged Bird SingsImportance of Being Earnest, TheInvisible Man (Ellison)Jane EyreJoy Luck Club, TheJungle, TheKing LearLesson Before Dying, ALife of PiLord of the Flies MacbethMedeaMerchant of Venice, The Metamorphosis, The Midsummer Night’s Dream, A Much Ado About Nothing Oedipus Rex Of Mice and Men Old Man and the Sea, TheOur TownPicture of Dorian Gray, ThePride and PrejudiceRaisin in the Sun, ARichard IIIRomeo and JulietScarlet Letter, TheSeparate Peace, A Siddhartha Slaughterhouse-FiveStreetcar Named Desire, ATale of Two Cities, ATaming of the Shrew, TheTempest, The Things Fall ApartThings They Carried, TheTo Kill a MockingbirdTranscendentalism Twelfth Night Wuthering HeightsP.O. Box 658, Clayton, DE 19938www.prestwickhouse.com 800.932.4593ISBN 978-1-935464-26-6Item No. 305044Copyright 2009 Prestwick House, Inc. All rights reserved.No portion may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher.2Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesA Message to theTeacher of LiteratureOpen your students’ eyes and mindswith this new, exciting approach to teaching literature.In this guide, you will find reproducible activities, as wellas clear and concise explanations of three contemporarycritical perspectives—feel free to reproduce as much, oras little, of the material for your students’ notebooks. Youwill also find specific suggestions to help you examinethis familiar title in new and exciting ways. Your studentswill seize the opportunity to discuss, present orally, andwrite about their new insights.What you will not find is an answer key. To the feminist, the feminist approach is the correct approach, justas the Freudian will hold to the Freudian. Truly, the pointof this guide is to examine, question, and consider, notmerely arrive at “right” answers.You will also find this to be a versatile guide. Use it inconcert with our Teaching Unit or our Advanced Placement Teaching Unit. Use it along with our Response Journal, or use it as your entire study of this title. Howeveryou choose to use it, we are confident you’ll be thrilledwith the new life you find in an old title, as well as inyour students.Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.3

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireTable of ContentsGeneral Introduction To The Work. 6Introduction to A Streetcar Named Desire. 6Genre. 7Plot Summary. 9Characters. 12Formalist Approach Applied to A Streetcar Named Desire. 13Notes on the Formalist Approach. 13Essential Questions for A Formalist Reading. 16Activity One: Analyzing the Repetitive Use of Musical Themes. 17Activity Two: Analyzing the Use of Costume to Develop the Character. 24Activity Three: Analyzing William’s Use of Motifs and Recurring Imagery. 30Discussion Questions. 34Essays Or Writing Assignments. 344Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesFeminist Theory Applied to A Streetcar Named Desire. 35Notes on the Feminist Theory. 35Essential Questions for A Feminist Reading. 38Activity One: Analyzing the Portrayal of Women as Dependent Upon Men. 39Activity Two: Discerning the Playwright’s Attitude Toward DomesticViolence. 46Activity Three: Examining Blanche’s Rape as Either Dramatic Device orMisogynistic Statement. 53Discussion Questions. 59Essays Or Writing Assignments. 59Psychoanalytic Theory Applied to A Streetcar Named Desire. 61Notes on the Psychoanalytic Theory. 61Essential Questions for A Psychoanalytic Reading. 64Activity One: Discerning the Relationship Between the Playwright and hisProtagonist. 66Activity Two: Exploring the Conflict Between the Id and Superego ofBlanche DuBois. 71Activity Three: Analyzing Stanley, Stella, and Blanche as the Three Aspectsof the Personality. 74Discussion Questions. 78Essays Or Writing Assignments. 78Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.5

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireGeneral Introduction to the WorkIntroduction to A Streetcar Named DesireOpening onDec. 3, 1947, A Streetcar Named Desire secured Tennessee Williams’s place in the pan-theon of American playwrights. With its raw depiction of alcoholism, sexuality—including anoffstage rape—and explosive human emotion, the play shocked and thrilled critics and audiences alike.The drama won for Williams the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes.Set in New Orleans, where Williams lived for a time, A Streetcar Named Desire tells the story of the colossal and ultimately disastrous culture clash between Blanche DuBois, a fragile aging Southern belle, proneto drink and mendacity, and Stanley Kowalski, her brutally masculine, blue-collar brother-in-law. StellaKowalski, sister to Blanche and wife to Stanley, forms the third point of this human Bermuda triangle.Elia Kazan, an award-winner producer and director of both films and stage play, and a successfulplaywright and novelist, directed the Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire, as well as the1951 film version. The drama introduced audiences to the raw power of a 23-year-old actor namedMarlon Brando and starred a young Jessica Tandy in the stage production.In later years, Williams confirmed that when he wrote the play, he intended for Blanche to be themore sympathetic character, a relic of the South’s past, destroyed by the barbaric Stanley. However, audiences thrilled to Brando, whose performance overpowered his costars. According to an Internet MovieDatabase biography of Brando, Kazan feared the audience was becoming too enamored of Brando andsuggested toning down the part, lest the actor’s power undermine the audience’s sympathy for Blanche.Williams, who also was enthralled with Brando, was not worried and permitted the actor to exercise hisfull range of power.As with many of Williams’s works, A Streetcar Named Desire contains overt and subtle autobiographical elements. Williams, who was openly homosexual, struggled for much of his life with alcoholism anddepression, much like his protagonist, Blanche.The movie garnered twelve Academy Award nominations and won four Oscars for best actress (VivianLeigh), best supporting actress (Kim Hunter), best supporting actor (Karl Malden) and best art direction.Ironically, Brando, who remains the actor most identified with Streetcar, and director Kazan, the personmost responsible for bringing Williams’s work to life, were nominated for Oscars but did not win.6Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesGenreA Streetcar Named Desire is a one-act play with eleven scenes. The work is a tragedy, a serious dramain which the problems and flaws of the central characters lead to an unhappy or catastrophic ending. Theoriginal Greek word tragoidia roughly means “the song of the goat,” from tragos (goat) and oide (ode orsong). The structure of the classic dramatic tragedy, as outlined by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, isunified by place, time, and plot. In other words, the story is set in a single location, within a discrete timeperiod, and is built around a series of actions that pertain to a single, central plot. In a classic tragedy,the story is told in a straightforward, chronological fashion, as the rising action builds toward a crisisand then the climax. The falling action is often brief, resulting in a swift denouement (outcome or finalsolution.) In the case of a tragedy, the unhappy resolution is known as the catastrophe.A Streetcar Named Desire fits the standard parameters of a dramatic tragedy. The Kowalski apartment,where all the onstage action occurs, provides the unity of place. The story develops chronologically overthe course of a few months, creating the unity of time. Facts about Blanche’s past are revealed throughdialogue, rather than flashbacks, and serve to develop and explain the forward-moving plot. There isonly one plot—the conflict between Blanche and Stanley. Stella and Mitch serve to complicate andenhance that plot, but they do not have storylines of their own. Likewise, the minor characters, Euniceand Steve Hubbell, are not central to any subplot; their squabbles merely echo the front-and-center fightsbetween Stanley and Stella.In a classic tragedy, the tragic hero meets with an unhappy end—usually his or her utter destruction,brought about by a combination of outside forces and his or her own fatal flaws. In Streetcar, Blanche isthis tragic hero. Her past is a mixed bag. She has apparently sacrificed some part of her own happiness inorder to tend to her dying relatives in Laurel, Mississippi, and witnessed the loss of the family home—aloss that she was powerless to stop. At the same time, she herself callously and thoughtlessly destroyed asensitive soul and has spent her life since that defining event engaging in morally questionable behaviorwith assorted men, including a student.As the play unfolds, she desires to be Stella’s rescuer, but ultimately is unable to accomplish anything. The most action she takes toward extricating her sister and herself from Stanley and his abuse isto pretend to telephone and write to a man who is little more than a figment of her imagination.Likewise, her attempt to secure her own happiness is essentially neurotic, deceitful, and manipulative. When Stanley learns the truth and uses it against her, she is undone by her own weaknesses (socialpretension, alcoholism, mendacity, and a fixation with the past). Stanley is the antagonist who pursuesher, exposes her weaknesses and secrets, and ultimately destroys her.Tennessee Williams wrote dozens of short one-act plays, including his first play, “Beauty Is theWord,” written in 1930 while he was in college. He seemed drawn to the unity of the form, as wellas to the tautness of the structure. Drama critics have theorized, also, that the one-act structure madeWilliams’s work more adaptable to film.Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.7

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireAs a one-act play, A Streetcar Named Desire differs somewhat in structure from the more traditionaltwo- or three-act dramatic structures. The playwright did not designate an intermission break within theoriginal script. However, most theatrical companies do include an intermission, selecting whatever theyconsider to be a dramatic high point to interrupt the flow of the action into two “acts.”In a typical three-act play, each act ends on a significant plot point. In A Streetcar Named Desire, mostcritics agree that these plot points are found in Scene Three and Scene Eight. Collectively, the plot pointsbuild toward the climax in Scene Ten. Each scene can be studied as a contained unit, as the action risestoward the plot points and ultimate climax. Most of the scenes also end on a note of tension or suspense,usually reinforced by the musical score. (The Blue Piano music ends seven of the eleven scenes, whilethe Varsouviana Polka closes two.)8Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesPlot SummaryScene One begins on what Williams describes as “the first dark of an early evening in May.” Thesky is a “peculiarly tender blue, almost turquoise.” The setting is Elysian Fields Avenue in New Orleans,a poor neighborhood, but with a “raffish charm.” The main set is a two-story house with steps leadingfrom the street to both apartments. Screens, projections, and lighting effects will allow walls to appearand disappear, at times showing the exterior of the house, while at others revealing the inside. At thebeginning of the play, the exterior of the house is showing.Stanley Kowalski and his friend Mitch enter boisterously, and Stanley bellows for his Stella. Sheappears on the landing of the first-floor apartment, in a pose that is probably supposed to be reminiscentof the balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet. Stella upbraids Stanley for “hollering” at her, and he tosses hera package of meat and tells her he is going bowling. She follows soon after to watch.Enter Blanche DuBois, Stella’s older sister, and the protagonist of the play. She is described as mothlike, her white suit, hat, and gloves making her look “incongruous to [the] setting.” She appears to belost, but Stanley and Stella’s upstairs neighbor convinces her that she has indeed arrived at the correctaddress. Blanche informs the neighbor that she rode the streetcar line named “Desire,” transferred to the“Cemeteries” line, and finally arrived at Elysian Fields (Avenue).Blanche is appalled by her sister’s apartment. In the space between her entrance and Stella’s return,she finds the whiskey, helps herself to a generous drink, and then hides the evidence.Stella returns, and in the sisters’ reunion, the audience learns that Stella was expected but arrivedseveral weeks early. She has apparently taken a leave of absence (or been given a leave of absence) fromher teaching job. The most important revelation, however, is that the DuBois family plantation, BelleReve, has been lost. It apparently fell to Blanche to care for a parade of aged and ill relations—all ofwhom eventually died—with dwindling resources except for her teacher’s salary. She expresses bitternessthat Stella was not available to help, arriving only for the funerals, never witnessing the suffering thatpreceded them. For her part, Stella insists that the only thing she could have done was leave the plantation and support herself.Stanley returns and meets Blanche. Immediately there is tension between them—especially afterStanley notices that Blanche has been drinking his whiskey and then claims that she hasn’t. He asks herabout her own marriage, and the audience learned that her husband, whom she call a “boy,” died.In Scene Two, Stanley learns of the loss of Belle Reve, and the audience has its first glance of Stanley’snear-violent temper. He is confident that Blanche has somehow cheated Stella (and by extension him)out of her rightful inheritance. He mistakes her ragtag wardrobe for expensive clothing and cheap pasteand rhinestones for valuable jewels. He reveals his own lack of sophistication by insisting that he knowspeople who can appraise Blanche’s “treasures,” so he and Stella will know the truth of how Blanche hassquandered their fortune. It is revealed, however, that the plantation was mortgaged and foreclosed upon,and Blanche is penniless. Stanley’s tantrum and Blanche’s reaction to his pawing through her belongings,widens the rift between them.Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.9

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireScene Three is poker night. The audience meets Mitch, who is more sensitive than the other men inthe play, as he cares for his ailing mother. Blanche acts flirtatiously and “lady-like” before the men who,with the exception of Mitch, are far from gentlemanly. Mitch and Blanche seem to hit it off, suggestingthat a relationship might develop between them, but Blanche and Stella anger the drunk Stanley, whothrows a violent outburst and hits Stella. The sisters flee, but Stella soon returns to Stanley in a reconciliation with obvious sexual undertones.Scene Four allows the audience to see the growing rift between the sisters. Blanche is appalled atStella’s current life and implores her to remember their superior upbringing. She remembers a formerbeau (now married) whom she ran into the following winter, and she insists that he will give the sistersthe money to free themselves from their current situation. Stella insists that she does not desire to be“freed,” and she again alludes to the physical passion she and Stanley share. Stanley overhears Blanche’sdismissing him as common and animalistic, and the scene ends with Stella embracing him—obviouslyallying herself with her husband—as he addresses Blanche in a tone that clearly suggests to the audiencethat he intends to destroy her.In Scene Five, Blanche is writing a letter to her former/imaginary beau, asking for money to escape theKowalski apartment. The upstairs neighbors have a fight similar to the one we witnessed between Stanleyand Stella in Scene Three. Stanley confronts Blanche with some evidence of her tawdry past and her currentlies—a man he works with knows of Blanche’s reputation and the fact that she lived for a while in a hotelknown for prostitution. Alone in the apartment, waiting for Mitch to arrive for a date, Blanche attempts toseduce a young man collecting for the evening paper. She chastises herself, suggesting to the audience thatthis kind of thing has happened before. Mitch arrives, and they go on their date.In Scene Six, Mitch and Blanche return from their date, tired and dispirited. Mitch treats Blancheas if she were a naive, unspoiled girl—and it is clear that Blanche has given him that impression. Theyconfide in one another—Mitch’s self-consciousness about his size and appearance, and Blanche’s marriage to a sensitive young man she discovered was a homosexual. When she confronted her husbandand told him that he disgusted her, he committed suicide. The music that was playing the night of thesuicide (the Varsouviana Polka) and the sound of the gunshot have haunted Blanche ever since. Mitchresponds tenderly, admitting that he needs someone, and Blanche needs someone. The scene ends withthe expectation that a serious romance is developing for the two of them.Scene Seven begins with the preparations for Blanche’s birthday celebration. While Blanche is bathing, yet again, Stanley tells Stella all the details of Blanche’s debauched past in Laurel, Mississippi. Thetruth of Blanche’s life is underscored by Blanche herself singing songs about illusion and deception.Stanley tells Stella that he told Mitch what he knew about Blanche. By the time Blanche emerges for hercelebration, the tension on stage is palpable.Scene Eight depicts the celebration itself. The atmosphere is tense, and Mitch is conspicuouslyabsent. Blanche, ever the fan of illusion, tries to create a festive air. As a “birthday present,” Stanley givesBlanche a one-way bus ticket back to Laurel, Mississippi. As he is ready to leave to go bowling, Stellagoes into labor and asks Stanley to take her to the hospital.10Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesIn the aftermath of the birthday party, in Scene Nine, Blanche is drinking and haunted by the musicto which her young husband killed himself. Mitch arrives, and they have a confrontation about the liesshe has told him. She insists they were not “lies” but versions of the truth as it should have been. Sheadmits her affairs with soldiers, various other anonymous men, even a high school student. This last wasthe event that resulted in her being asked to leave her job and leave town. She had nowhere to go butStella’s apartment. When she asks Mitch to marry her, he says that she isn’t “clean enough” to take hometo his mother.Scene Ten reveals an almost-completely unraveled Blanche dressed in an ancient, wrinkled, andsoiled debutante gown and rhinestone tiara. She is drunkenly and psychotically reliving a night fromher past when Stanley enters with the news that the baby is not yet born, and he has been sent home torest. Blanche claims that she has received a telegram from her former/imaginary beau, inviting her on acruise of the Caribbean. She also claims that, after their initial confrontation, Mitch returned with rosesto apologize, and she broke it off with him in order to accept her beau’s invitation. Stanley confrontsher with her lie, and as he attacks her emotionally and psychologically, destroying every illusion she hasspent the play creating, he also attacks her physically, carrying her off stage, where he will rape her.Scene Eleven shows the catastrophe, the disastrous resolution of the tragedy. Stella, now a mother,ambiguously admits that she believes Blanche’s accusation that Stanley raped her, but chooses not to inorder to stay with her husband. The now thoroughly destroyed Blanche is taken to a state mental hospital, and a broken Mitch watches in despair. The play ends with Stanley assuring Stella that everythingwill be all right, and the men in the apartment playing another game of poker.Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.11

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireCharactersBlanche Dubois – The protagonist, Blanche is an aging Southern belle, given to pretension, self-delusion,and drink. Her name, Blanche, means “white” in French; DuBois means “of the woods.” She is theonly character to appear in every scene.Stanley Kowalski – The antagonist, Stanley is raw, masculine power. Coarse and animal-like, he seeks tocontrol his world and everything in it.Stella Dubois Kowalski – Married to Stanley, Stella is Blanche’s younger sister. Pregnant and completelyin love with her husband, she is occasionally caught in the cross-fire between Blanche and Stanley.Her name means “star.”Harold Mitchell – Known as “Mitch,” he is Stanley’s friend, coworker, poker buddy, and a veteran of the sameArmy unit. For a while, he dates Blanche, and a serious romance almost develops between them.Eunice Hubbell – A friend to Stella, she and her husband own the house where the Kowalskis live andoccupy an apartment upstairs.Steve Hubbell – A minor character, he plays poker with Stanley and is married to Eunice.Pablo Gonzales – A poker player, he completes the foursome with Stanley, Steve, and Mitch.Nurse – An unnamed woman, her job is to escort Blanche to a mental hospital.Doctor – An unnamed man, he has been sent to take Blanche to a mental hospital.Negro Woman – Appearing only in Scenes One and Ten, she exemplifies the loose social conventions ofNew Orleans.A Young Collector – Blanche’s attempted seduction of the young man foreshadows the revelation abouther seduction of a student.A Mexican Woman – Her cry of “flores para los muertos” punctuates Blanche’s reminiscence about deathand loss. 12Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectivesFormalist Approach Appliedto A Streetcar Named DesireNotes on the Formalist ApproachThe formalist approach to literaturewas developed at thebeginning of the 20th century and remained popular until the1970s, when other literary theories began to gain popularity. Today,formalism is often dismissed as a rigid and inaccessible means ofreading literature, used in Ivy League classrooms and as the subjectof scorn in rebellious coming-of-age films. It is an approach that isconcerned primarily with form, as its name suggests, and thus placesthe greatest emphasis on how something is said, rather than what issaid. Formalists believe that a work is a separate entity—not at alldependent upon the author’s life or the culture in which the workis created. No paraphrase is used in a formalist examination, and noreader reaction is discussed.Originally, formalism was a new and unique idea. The formalistswere called “New Critics,” and their approach to literature becamethe standard academic approach. Like classical artists such as daVinci and Michaelangelo, the formalists concentrated more on theform of the art rather than the content. They studied the recurrences,the repetitions, the relationships, and the motifs in a work in orderto understand what the work was about. The formalists viewed thetiny details of a work as nothing more than parts of the whole. Inthe formalist approach, even a lack of form indicates something.Absurdity is in itself a form—one used to convey a specific meaning(even if the meaning is a lack of meaning).The formalists also looked at smaller parts of a work to understand the meaning. Details like diction, punctuation, and syntax allgive clues.Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.13

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireThree main areas of study: form diction unity1. Form Cadence—how the words sound. When a character or a narrator is speaking, the sound of whathe or she is saying, or how he or she is saying it, can give clues as to who the character is and whyhe or she is in the work. Repetition—saying the same word, phrase, or concept over and over. Obviously, when somethingis repeated several times, it must be important. Recurrences—when an event or a theme happens more than once. Like repetition, when something is repeated, it is for a reason. Relationships—the connections between the characters. By looking carefully at the connectionsamong the people in the story, one can understand the meaning of a work. Every character is putinto the story for a reason. The reader’s job is to find that reason.2. Diction Denotation—the dictionary definition of a word. Obviously, understanding the meaning of thewords used is vital to understanding a text. If a reader does not know what the words mean, he orshe can have no idea what is being said. Connotation—the subtle, commonly accepted meanings of words. Even though a word may technicallymean one thing, the way it is used in society will often place a slightly different spin on the word. Takefor instance the word “condescension.” Though it literally means “the act of coming down voluntarilyto equal terms with a supposed inferior to do something,” modern use of the word gives it a negativecast—when someone “condescends” now, he or she is acting superior to someone else. Etymology—the study of the evolution of a word’s meaning and use. Etymology is especially helpful when one is studying an old text in which the words might literally mean something differentfrom what they mean today. A close study of words also helps a reader understand why the authoruses a particular word rather than a synonym.14Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.

A Streetcar Named DesireMultiple CriticalPerspectives Allusions—links from the text at hand to other works. Though this area is less formalist than theothers (because it reaches outside of a text for meaning), it is still valuable to consider all of the“connotations” of the word used. There is a reason the author wanted to link his or her text to thatof another author, and studying the allusion is the only way to reveal that reason. Ambiguity—is the use of an open-ended word or phrase that has multiple meanings. Just as theformalist asserts that a lack of form is a form, ambiguity can be used to connect several loose endsin a work. The author can use ambiguity to help reveal his or her meaning. Symbol—a concrete word or image used mainly to represent an abstract concept. Understandingthe use of a word or image to suggest deeper meanings can help a reader gain more from the text.The meaning of the text can be found in the many facets of a symbol.3. Unity The use of one symbol, image, figure of speech, etc. throughout a work serves as a thread toconnect one particular instance with every other occurrence of that symbol. Unity helps remindthe reader of what has already happened and shows him or her how what is happening currentlyrelates to earlier events or forthcoming events. Formalist critics do not look for perfect unity. They look for tension and conflict. Irony and paradox are very important—irony being the use of a word or a statement that is the opposite of whatis intended or expected, and paradox being the existence of two contradictory truths. This tensionis what drives the work. Pr e s t w i c kHo u s e,In c.15

Multiple CriticalPerspectivesA Streetcar Named DesireEssential Questions for A Formalist Reading1.Does the work exhibit the chara

Joy Luck Club, The Jungle, The King Lear Lesson Before Dying, A Life of Pi Lord of the Flies Macbeth Medea Merchant of Venice, The Metamorphosis, The Midsummer Night’s Dream, A Much Ado About Nothing Oedipus Rex Of Mice and Men Old Man and the Sea, The Our Town Picture of Dorian Gray,