Transcription

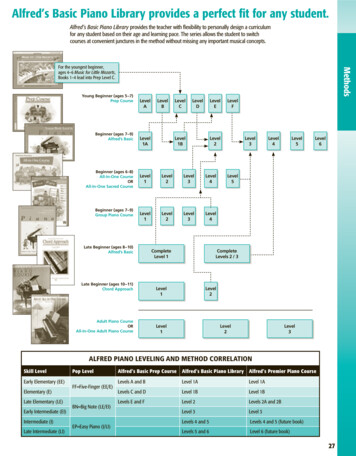

DECEMBER UPDATEStatewide High-Level Analysis of ForecastedBehavioral Health Impacts from COVID-19PurposeThis document provides a brief overview of the potential statewidebehavioral health impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic. The intentof this document is to communicate potential behavioral healthimpacts to response planners and organizations or individuals whoare responding to or helping to mitigate the behavioral healthimpacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.Bottom Line Up Front The COVID-19 pandemic strongly influences behavioral healthsymptoms and behaviors across the state due to far-reachingmedical, economic, social, and political consequences. Thisforecast is heavily informed by disaster research and response,and the latest data and findings specific to this pandemic.Updates will be made monthly to reflect changes in baselinedata. For the last several weeks, the risk of a disaster cascade (morethan one disaster impact within a short period of time) hasincreased significantly. Secondary disaster impacts are oftenrelated to or triggered by the initial impact, and may includeeconomic hardships (unemployment, bankruptcy, eviction, andfood insecurity, etc.) and social and political disturbances(violence, civil unrest, protests, etc.). They can also be triggeredby additional natural disasters, such as the wildfires thatoccurred during the summer months and impactedcommunities already struggling with the pandemic. Any secondary disaster impacts within the next few months willalso be occurring during the height of the disillusionment phaseof the initial disaster recovery cycle that began in March 2020. Adisaster cascade extends response and recovery cycles andtends to increase both the severity and number of behavioralhealth symptoms many people experience.DOH 821-128December 2020To request this document in anotherformat, call 1-800-525-0127. Deaf orhard of hearing customers, pleasecall 711 (Washington Relay) or emailcivil.rights@doh.wa.gov. Ongoing behavioral health impacts in Washington continue tobe seen in phases (Figure 1), with symptoms for most peoplepeaking throughout the remainder of 2020 and into the first halfof 2021.1,2 This coincides with significant increases in rates ofinfection and hospitalization in our state.3 Early 2021 will likely be defined by an extension of thedisillusionment phase of disaster recovery, with the potential forimpacts of a disaster cascade. The risk of suicide, depression,hopelessness, and substance use historically are at their highestduring this phase of any disaster, matching what we arecurrently seeing. The need for professional behavioral health

support, as well as community resources, will likely be at their highest in the first few months of2021. This will be occurring at a time when community resources – that are already stretched –will have even less ability to support the increased need. Behavioral health experiences at this phase of the COVID-19 pandemic typically include symptomsof depression and anxiety, trouble with cognitive functioning, exhaustion, and burnout. Activeresilience development remains an essential intervention for all groups in our state. We expect behavioral health issues related to isolation, stress, and fears to worsen as COVID-19cases increase, which could escalate medical risks for greater numbers of people. 4,5,6,7Washington, as of12/22/2020*Figure 1: Phases of reactions and behavioral health symptoms in disasters.Adapted from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 8*The dotted graph line represents the response and recovery pattern that may occur ifthe full force of a disaster cascade is experienced by a majority of the population.Phase-Related Behavioral Health ConsiderationsBehavioral health symptoms will continue to present in phases.1,2 The unique characteristicsof this pandemic trend towards anxiety and depression as a significant behavioral healthoutcome for many in Washington. These outcomes have been shown throughout theBehavioral Health Impact Situation Reports published by the Washington State Department ofHealth, which are available on the Behavioral Health Resources & Recommendations webpage. aAs infection and hospitalization rates continue to rise significantly, symptoms of anxiety andrisk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to fears of illness or death from the virus,or direct experience of illness or death among family and friends are also likely to increase.9,10A disaster cascade is a circumstance in which multiple disasters occur with separate impacts, ora single disaster occurs with cascading outcomes over a relatively short timeframe.11,12 Anadditional consideration is the potential for a disaster cascade, which could occur if the currentrise in infections continues at a rate which triggers a secondary disaster impact (as December Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-192

by the dotted line in Figure 1). The secondary impact may be a result of the pandemic itself(illnesses and hospitalizations) or an indirect impact of the pandemic (economic hardship, socialand political unrest, etc.).In Washington, families who have been impacted by wildfires that occurred this year (and havebeen displaced or lost their homes) have already experienced a disaster cascade on anindividual and community level. If the winter months (of 2020–2021) drive exponentialinfection rates, causing corresponding public health, economic, and personal losses orstruggles, the consequences of a disaster cascade would be experienced widely. If this occurs, itis likely to happen when we are already in the disillusionment phase. b The behavioral healthissues common to that phase (depression, anxiety, and suicide risk) would then very likely bemore severe for many, and extend the reconstruction and recovery process (i.e., return tobaseline) by many months.11,13,14Certain populations, such as some ethnic and racial minorities, disadvantaged groups, those oflower socioeconomic status, and essential workers, continue to experience disproportionatelymore significant behavioral health impacts. 15,16,17,18 Healthcare workers, law enforcementofficers, educators, and people recovering from critical care may experience greater behavioralhealth impacts than those in the general population. The COVID-19 Behavioral Health GroupImpact Reference Guide,c provides detailed information on how people in specific occupationsand social roles are uniquely impacted.Specific Areas of Focus for First Quarter (January, February, March) of 2021Pandemic ApathyFor many people, the length of time that this pandemic has been influencing life has resulted inan experience where general exhaustion may be manifesting in the form of apathy about thepandemic. This seems to be characterized in a similar pattern to what is typically seen indisasters in terms of acting “out” and acting “in,” but unique in terms of apathy presenting onboth ends of the spectrum. (Please see pages 3–4 of the July forecast update d for moreinformation about the concepts of acting “out” and acting “in.”)On one end of the apathy spectrum, current anecdotal reports and examples suggest thatacting “out” may manifest as behaviors consistent with denial of the pandemic. Acting “out”may also include being so tired of managing the consequences of the pandemic, leading someindividuals to behave as if the current conditions don’t apply or exist (e.g., meeting with friendsand family, refusing to comply with recommended and mandated public health guidelines,conducting “business as usual”). The other end of the apathy spectrum includes acting “in,”which seems to be manifesting in extreme hopelessness, not caring about other people, andnot caring to engage or participate in much of anything at all (including work and daily tasks likechild care, self-hygiene, etc.), and seems to be consistent with some symptoms of majordepressive disorder.For a description of each phase in the disaster timeline, refer to page 5 of the COVID-19 Behavioral Health GroupImpact Reference ecember Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-193

Depression and Suicide RiskDepression is one of the most common emotional responses during the disillusionment phaseof disaster response and recovery. In Washington, this phase coincides with seasonal changes,such as reduced daylight hours and fall/winter weather conditions. When weather conditionschange and people are less likely to spend time outdoors for exercise or as part of a copingmechanism, mental health symptoms are likely to worsen. Many people relied on outdoorgatherings as a way to more safely interact with family and friends during the warmer monthsof 2020. Those options are far more limited during colder months with fewer daylight hours.The combination of these circumstances may result in an increase in symptoms of seasonalaffective disorder (depression that tends to recur chiefly during the late fall and winter and isassociated with shorter hours of daylight) beyond increases that are typical for this time ofyear. 19Many youth, teens, and young adults are experiencing significant symptoms of depressionduring the pandemic.20 Older adults are also a group of concern due to isolation and lack ofsocial connection. First responders, healthcare professionals, and behavioral health providersare also feeling emotional impacts of the pandemic as more patients and clients needtreatment, support, and preventive care.As the risk of depression increases throughout the disillusionment phase and the wintermonths, so too does the risk of suicide. Active suicide prevention should be promoted throughthe sharing of information about recognizing warning signs; e checking in with colleagues,friends, family members, and neighbors; and sharing resources. When someone is expressingthoughts of self-harm, remove access to dangerous means of harm,f and safely storingmedications, poisons, and firearms. Suicides consistently account for approximately 75% of allfirearm-related fatalities in Washington.21 Storing firearms safely g and temporarily removingthem from the home h of an at-risk person during a crisis can save lives.Additional Resources: Anyone concerned about depression or other behavioral health symptoms should talk withtheir healthcare provider.Washington Listens i (833-681-0211) is a hotline for people experiencing stress due toCOVID-19.Health Care Authority – Washington Mental Health Crisis Services j National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: k Call 800-273-8255 (English) or 1-888-628-9454 (Español). Crisis Connections: l Call 866-427-4747. Crisis Text Line: m Text HEAL to 741741. //www.crisistextline.org/December Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-194

Department of Health – Crisis Lines for Specific Groupsn TeenLink: o Call or text 866-833-6546. Washington Warm Line: p Call 877-500-9276. Washington State COVID-19 Response – Mental and emotional well-being webpage qExhaustionGeneral fatigue, exhaustion, and feeling overwhelmed are common experiences in thedisillusionment phase of disaster response and recovery. 22,23,28 Feeling exhausted can be bothcaused and worsened by problems with sleep, which commonly is disrupted by prolongedperiods of stress. Recognizing the need to engage in healthy sleep hygiene practices (going tosleep and waking around the same time each day), limiting blue light exposure (such as lightfrom computer screens and other digital devices), physical exercise, and practicing healthyeating habits will help to mitigate this symptom for children and adults. Long term exhaustionmay also contribute to other behavioral health symptoms, such as reduced or diminishedcognitive and higher-level thinking capacity. This too is also likely to be impacted by increasedstress in this phase. Exhaustion significantly worsens the personal impact of pre-existingbehavioral health symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or trauma, and can make it much fordifficult for individuals to deal with their mental health. As such, consistently working topractice self-care, particularly in the form of consistent and restorative rest, is a priority.Workplace Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Moral InjuryWorkplace burnout and similar phenomena for healthcare and human services workers havebeen increasing steadily in the last several months and will likely continue to do so for theremainder of 2020. 24,25 Compounding this issue is the concern that some workers’ concern thatthey may experience discrimination in the workplace for voicing concerns about mental health.Burnout is defined as exhaustion of body and mind when there is an unequal balance betweenthe demands of the job and the coping resources available to an employee. Compassion fatigueis emotional and physical tiredness leading to a decreased ability to empathize or feelcompassion for others. It is also described as secondary traumatic stress.Moral injury is defined as strong feelings of guilt, shame, and anger about the frustration thatcomes from not being able to give the kind of care or service that an employee wants andexpects to provide. During disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workersr arefrequently in situations where standards of care are altered due to patient surge and scarceresources, shifting from conventional care to contingency care or crisis standards of care.Having to practice outside of conventional care is an added psychological risk for healthcareworkers.22 As infection rates rise throughout the state, potentially causing a strain on medicalresources, issues of burnout and moral injury become increasingly likely for all types ofhealthcare workers in all care settings, including behavioral health providers. 26We are likely to continue to see an increase in the experiences of burnout, compassion fatigue,and moral injury for all types of healthcare workers due to the length and pervasiveness of thepandemic. Additionally, there will likely be workplace stressors related to economic ing-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/pqDecember Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-195

and divisiveness among people and groups. For information on mitigating these impacts, pleasesee the COVID-19 Guidance for Building Resilience in the Workplace. sCognitive and Emotional DisruptionsCognitive concerns and the tendency to react emotionally are hallmarks of long-term stress andtrauma, and are significant in the context of disaster response and recovery. 27,28 Many peopleare experiencing problems with memory (such as tracking details, attention, planning, andorganizational thinking) that impact the ability to function at home and at work. In addition tothese cognitive issues—in part as a function of them—many people are reacting in a moreemotional way than they otherwise might to neutral events and interactions.27Recognizing the way that the human brain functions in the context of a disaster and providingthat information publicly may help reduce the stigma around these cognitive issues and provideopportunities for many people to learn how to manage them more effectively. Normalizing theexperiences of stress and trauma affecting the brain, body, and functioning helps increaseresilience.Substance UseAccording to the Washington Poison Center (WAPC), there are recent and concerning trends foradolescents and teens. Specifically, in children ages 6–12, 35% used cannabis in 2019 comparedto 41% in 2020. For youth ages 13–20, those numbers jump from 63% in 2019 to 78% in 2020.29Relative to 2019, exposures to THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, one of many chemicalcompounds in cannabis products) reported to WAPC increased 20% in adults ages 21–59 years.There are similar concerns regarding adults over 60 years old related to medication errors andthe misuse of household cleaning products and disinfectants.30 There is also data to suggest ahigher call volume to the WAPC about the intentional use of substances for self-harm or abuse.It is important to help older adults with medication management to avoid errors, and toencourage regular preventative care appointments in order to foster support and preventionrelated to self-harm or suicidal ideation.Recent research has also identified a concerning trend around increased alcohol use in women.This may reflect the multitude of responsibilities that many working women have been facedwith, such as managing home-schooling and trying to maintain employment throughout thepandemic. 31 Substance use will likely continue to be a problematic coping choice for many, withthe potential for further increases moving into 2021. 32 Parenting in the context of work andother life demands can also be affected by substance use and misuse. Though substance usemay be a coping tool for many, it could quickly contribute to an unhealthy environment forboth children and adults. Individuals concerned about substance use are encouraged to talkwith their healthcare provider. Visit the state’s coronavirus response well-being webpageq forresources to help with substance use.Continued Efforts Toward Personal and Community ResilienceThe continued development of psychological resilience (adaptability and flexibility, connection,purpose, and hope) should be strongly encouraged throughout the next several months. Pleasesee the Born resilient article, t The Ingredients of Resilience infographic, u and the COVID-19Guidance for Building Resilience in the Workplaces for more information on resilience.Encouraging people to engage in healthy outdoor activities as a way of active coping is 0Resilience.pdfstDecember Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-196

recommended when group size is limited appropriately, and safe social or physical distancingcan be maintained.Community resilience is the capacity of individuals and households within a community toabsorb, endure, and recover from the impacts of a disaster. Approximately 50% of Washingtonresidents have one or two risk factors that can threaten resilience, including unemployment,single parenting, economic inequality, or pre-existing medical conditions. 33 Resilience can beactively developed both on individual and community levels. Creative social connection as apart of resilience building can also be encouraged and developed. It can be amplified toincrease social connection. This helps reduce behavioral health symptoms and encouragesdevelopment of active coping skills for the population at large.The typical long-term response to disaster is resilience, rather than disorder.1,34 Resilience issomething that can be intentionally taught, practiced, and developed for people across allgroups. Resilience can be increased by: 35 Becoming adaptive and psychologically flexible. Focusing on developing social connections, big or small. Reorienting and developing a sense of purpose. Focusing on hope.Community support groups, lay volunteers, and social organizations and clubs are resourcesthat can be developed to help reduce behavioral health symptoms for the general population.These should be leveraged to reduce demand on depleted or unavailable professional medicaland therapeutic resources throughout 2021.Organizational ResilienceOrganizational resilience can be developed by focusing on the main elements of resilience andidentifying some specific ways in which organizations can be successful in this phase of the COVID-19pandemic. Recommendations include: Developing shared trust and interdependence among employers and employees. Enhancing the organization’s ability to learn and adapt to lessons learned. Human Resources flexibility for work schedules and boundaries, time off, and job roles. Open, two-way communication among leadership and staff at all levels about expectationsand goals. 36,37For more detailed information on how to support and build workplace resilience, please see theCOVID-19 Guidance for Building Resilience in the Workplace.sPotential for Violence and AggressionIncreases in handgun sales present more risk for gun violence.38,39 Most notably, handgunownership is associated with a significantly increased and enduring risk of suicide by firearm.40The FBI has conducted 35,758,249 background checks nationwide for gun purchases and otherrelated services from January–November 2020. 3,626,335 background checks occurred inNovember alone. In comparison, the FBI conducted a total of 28,369,750 background checks forgun purchases in the year 2000.40 Some ways to decrease risk v are to keep all firearms securelylocked up, prevent unauthorized access by children, and ask a friend or relative to take firearmsin an emergency transfer until the crisis is -a-safer-home/December Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-197

The combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the election season has caused a significantincrease in sociopolitical discord, extremist views, and extremist behaviors, according to a U.S.Department of Homeland Security threat assessment.41 Generally, there is a higher risk ofviolence related to political tension during election season. In the context of the COVID-19pandemic, that risk of violence is elevated during this election season.41 With heightenedemotions due to the pandemic, increased extremist behavior, and increased gun sales, it ismore important than ever for people and communities to promote resilience, increaseconnection, be mindful of what others may be experiencing, and be intentional about practicingpatience.Children and FamiliesAlmost 30% of parents are experiencing negative mood and poor sleep quality, with a 122%increase in reported work disruption and 86% of families experiencing hardships, such as loss ofincome, job loss, increased caregiving burden, and household illness. Families experiencinghardship are also reporting navigating their child’s disruptive or uncooperative behavior andanxiety. 42 When children go through a hard time, such as living through a disaster, they willneed extra attention, comfort, and attention from their parents. It’s important to try to bepatient with the child who is upset and may be having tantrums or becoming withdrawn. It’salso important to try to keep the family rules about behavior the same, if possible. Whenchildren don’t have help with boundaries and limits on their behavior, it can make them feelless safe and more anxious.It is also important to note that mental health-related visits to emergency departments forchildren ages 5–17 between April and October of 2020 increased by 24–31%, compared withthe same time period in 2019.43 It is normal for children to be experiencing difficulty during thistime, but if you have concerns about safety, please reach out for professional support andassistance. For more detailed information on this topic, see the Behavioral Health Toolbox forFamilies: Supporting Children and Teens During the COVID-19 Pandemic. w This resourceprovides general information about common emotional reactions of children, teens, andfamilies during disasters. It also has suggestions on how to help children, teens, and familiesrecover from disasters and grow stronger.Suicidal Ideation and Attempts in YouthWe are continuing to monitor rates of emergency department visits for psychological distress,suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts for adolescents, youth and young adults. Theconvergence of factors that may be uniquely affecting the psychological health of these groupsin our state leading into 2021 is very concerning. There are a number of factors, including thecurrent disillusionment phase of disaster, as well as the unique challenges faced by youngpeople this year, that may contribute to an increase in distress.We are strongly recommending continual monitoring and supporting of adolescents and youth.For parents and caregivers, this can include checking in and asking youth and teens aboutthoughts of self-harm or suicide. Asking about suicide does not increase risk and, in fact,increases safety and often helps lead to timely intervention. For medical and behavioral healthproviders, this includes screening for suicidal ideation and behaviors, and regularly checking inabout access to means, such as substances or firearms, for inflicting self-harm of any ber Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-198

Child AbuseChild abuse and domestic violence often increase significantly in post-disaster settings, such asthe COVID-19 pandemic. 44,45,46 Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) among very young children arethe most commonly studied and among the most concerning form of injury due to child abuseafter a disaster.44 The national rate of emergency department (ED) visits related to child abuseand neglect resulting in hospitalization has increased among children across all ages, comparedwith 2019.47 While we don’t have clear evidence of increasing numbers of child abuse-relatedED visits in Washington (yet), we are very concerned and want to make sure families have thesupport they need during these challenging times. 48Due to school closures and social distancing measures, more children and youth are online andunsupervised than usual. Predators that are sexually interested in children are using thisopportunity to entice children to produce sexually explicit material (i.e., online enticement). 49National rates of online enticement of children have increased 98.66% – from 15,220 reports in2019 to 30,236 in 2020 – during the January–September time period.Additionally, as child traffickers have adjusted to the reluctance of buyers to meet in person toengage in commercial sex, some traffickers are now offering virtual subscription-based servicesin which buyers pay to access online images and videos of the child being sexually abused.Accordingly, compared to the January–September time period of 2019, there has been a63.31% increase in National CyberTipline reports (i.e., reports of distribution of childpornography and child sexual abuse material) for the same time period in 2020 (11,286,674reports in 2019 versus 18,423,495 in 2020).49 According to Seattle Police Department’s InternetCrimes Against Children (ICAC) Unit, which processes all statewide data of this nature,Washington CyberTips and online enticement reports are following the same trends asnational-level data.In an online setting, most educators and healthcare providers are asking for a parent orcaregiver to be present during all the interactions between the child and educator or provider.This may change or limit the opportunities for an educator/provider to ask the child directly orinquire about the way things are going at home. Typical cues that educators/providers use tospot signs of abuse or neglect may not be applicable in an online environment.Potential signs of child abuse or neglect that may be visible in an online setting: Changes in levels of participation in online classes (unusually vocal, disruptive, verywithdrawn, frequently absent or late to class, leaving early without explanation or notice,not wanting to leave). Extremely blunted or heightened emotional expressions. Appearing frightened or shrinking at the approach of an adult in the home. Age-inappropriate or sexualized knowledge, language, drawings, or behavior. Observable bruising on face, head, neck, hands, or arms (that is atypical for an active childof that developmental age). Recognize that children can have bruises for many reasons(e.g., rough playing, climbing). A change in the child’s general physical appearance or hygiene (e.g., a child that normallypresents in weather-appropriate clothing is no longer doing so, or a child that normallyappears clean begins to appear with consistently greasy hair). Indications that a young child may be home alone.December Update: Statewide High-Level Analysis of Forecasted Behavioral Health Impacts from COVID-199

Observable signs in the background of health or safety hazards, harsh discipline, violence,substance abuse, or accessible weapons. Keep in mind that substance misuse is not, byitself, reason for removing a child from the home. Parent or caregiv

Call or text 866-833-6546. Washington Warm Line: p. Call 877-500-9276. Washington State COVID-19 Response - Mental and emotional well-being webpage. q. Exhaustion . General fatigue, exhaustion, and feeling overwhelmed are common experiences in the disillusionment phase of disaster response and recovery. 22,23,28. Feeling exhausted can .