Transcription

Table of ContentsAbout the AuthorBy the Same AuthorTitle PageCopyright PageTitlePart One The Four Noble TruthsChapter One Entering the Heart of theBuddhaChapter Two The First Dharma TalkChapter Three The Four Noble TruthsChapter Four Understanding theBuddha's TeachingsChapter Five Is Everything Suffering?Chapter Six Stopping, Calming,Resting, HealingChapter Seven Touching Our SufferingChapter Eight Realizing Well-BeingPart Two The Noble Eightfold PathChapter Nine Right ViewChapter Ten Right ThinkingChapter Eleven Right M indfulnessChapter Twelve Right SpeechChapter Thirteen Right ActionChapter Fourteen Right Diligence

Chapter Fifteen Right ConcentrationChapter Sixteen Right LivelihoodPart Three Other Basic Buddhist TeachingsChapter Seventeen The Two TruthsChapter Eighteen The Three DharmaSealsChapter Nineteen The Three Doors ofLiberationChapter Twenty The Three Bodies ofBuddhaChapter Twenty-One The ThreeJewelsChapter Twenty-Two The FourImmeasurable M indsChapter Twenty-Three The FiveAggregatesChapter Twenty-Four The FivePowersChapter Twenty-Five The SixParamitasChapter Twenty-Six The SevenFactors of AwakeningChapter Twenty-Seven The TwelveLinks of Interdependent Co-ArisingChapter Twenty-Eight Touching theBuddha Within

Part Four DiscoursesDiscourse on Turning the Wheel of theDharma Dhamma Cakka PavattanaSuttaDiscourse on the Great FortyM ahacattarisaka SuttaDiscourse on Right View SammaditthiSuttaIndexAlso available from Rider. . .Peace is Every StepLiving Buddha, Living Christ

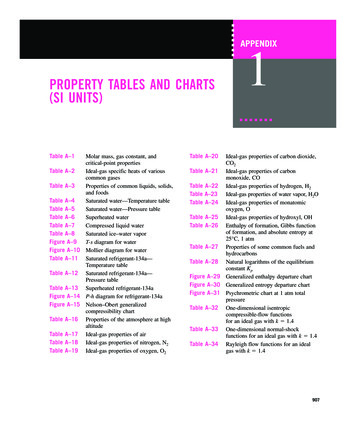

Figures1. The Four Noble Truths 102. The Twelve Turnings of the Wheel 303. The Interbeing of the Eight Elements of thePath 574. The Six Paramitas 1935. Seeds of M indfulness 2086. The Wheel of Life 2287. The Three Times and Two Levels of Causeand Effect 2338. The Interbeing of the Twelve Links 2359. Twelve Links: The Two Aspects ofInterdependent Co-Arising 24610. Twelve Links: The Two Aspects ofInterdependent Co-Arising 247

Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen master,poet, best-selling author and peace activist, hasbeen a Buddhist monk for over 40 years. He waschairman of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peacedelegations during the Vietnam War and wasnominated by Dr M artin Luther King for theNobel Peace Prize. In 1966 he visited the UnitedStates and Europe on a peace mission and wasunable to return to his native land. Today he headsPlum Village, a meditation community insouthwestern France, where he teaches, writes,gardens and aids refugees worldwide.'Thich Nhat Hanh writes with the voice of theBuddha.'Sogyal Rinpoche'Thich Nhat Hanh is more my brother thanmany who are nearer to me in race and nationality,because he and I see things in exactly the sameway.'Thomas Merton

Other Books by Thich Nhat HanhBe Still and KnowBeing PeaceThe Blooming of a LotusBreathe! You Are AliveCall Me by My True NamesCultivating the Mind of LoveThe Diamond That Cuts through IllusionFor a Future To Be PossibleFragrant Palm LeavesThe Heart of UnderstandingHermitage among the CloudsInterbeingLiving Buddha, Living ChristThe Long Road Turns to JoyLove in ActionThe Miracle of MindfulnessOld Path White CloudsOur Appointment with LifePeace Is Every StepPlum Village Chanting and Recitation BookPresent Moment Wonderful MomentStepping into FreedomThe Stone BoyThe Sun My HeartSutra on the Eight Realizations of the Great Beings

A Taste of EarthTeachings on LoveThundering SilenceTouching PeaceTransformation and HealingZen Keys

The Heart of theBuddha's TeachingTRANSFORMING SUFFERING INTOP EACE, JOY, & LIBERATION:THE FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS,THE NOBLE EIGHTFOLD P ATH, ANDOTHER BASIC BUDDHIST TEACHINGSThich Nhat Hanh

This eBook is copyright material and must notbe copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed,leased, licensed or publicly performed or used inany way except as specifically permitted in writingby the publishers, as allowed under the terms andconditions under which it was purchased or asstrictly permitted by applicable copyright law.Any unauthorised distribution or use of this textmay be a direct infringement of the author's andpublisher's rights and those responsible may beliable in law accordingly.ISBN 978-1-4090-2054-7Version 1.0www.randomhouse.co.uk

9 10Copyright 1998 by Thich Nhat HanhThe right of Thich Nhat Hanh to be identifiedas Author of this work has been asserted by him inaccordance with the Copyright, Designs andPatents Act, 1988.This electronic book is sold subject to thecondition that it shall not by way of trade orotherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwisecirculated without the publisher's prior consent inany form other than that in which it is publishedand without a similar condition including thiscondition being imposed on the subsequentpurchaserPublished in 1998 by Broadway Books,1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036,USAThis edition published in 1999 by Rideran imprint of Ebury PressRandom House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, LondonSW1V 2SAwww.randomhouse.co.uk

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited20 Alfred Street, M ilsons Point, Sydney,New South Wales 2061, AustraliaRandom House New Zealand Limited18 Poland Road, Glenfield,Auckland 10, New ZealandRandom House (Pty) LimitedIsle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road &Carse O'GowrieHoughton 2198, South AfricaRandom House Publishers India PrivateLimited301 World Trade Tower, Hotel IntercontinentalGrand Complex,Barakhamba Lane, New Delhi 110 001, IndiaThe Random House Group Limited Reg. No.954009www.randomhouse.co.ukSignificant portions of this text were translatedby Sister Annabel Laity from the Vietnamesebook, Trai tim cua But.Edited by Arnold Kotler.

Figures by Gay Reineck.Book design by Legacy M edia.Index by Brackney Indexing Service.Chinese characters courtesy of Rev. Heng Sure.Wheel of Life on p. 228 from Cutting ThroughSpiritual Materialism, byChögyam Trungpa, 1973. Published byarrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc.,BostonA CIP catalogue record for this book isavailable from the British LibraryISBN: 978-1-4090-2054-7Version 1.0To the reader:Unless otherwise noted, the terms that appear inparentheses throughout the text are in Sanskrit.Sanskrit has been transliterated informally, withoutthe diacritical marks. The s and s nave been writtenas sh. Sanskrit and other foreign terms are italicizedthe first time they appear, and definitions areprovided at that time. Textual sources are providedin full die first time they are cited; after that, only

author and tide are noted.

The Heart of theBuddha's Teaching

PART ONEThe Four Noble Truths

CHAPTER ONEEntering the Heart of the BuddhaBuddha was not a god. He was a human beinglike you and me, and he suffered just as we do. Ifwe go to the Buddha with our hearts open, he willlook at us, his eyes filled with compassion, andsay, "Because there is suffering in your heart, it ispossible for you to enter my heart."The layman Vimalakirti said, "Because theworld is sick, I am sick. Because people suffer, Ihave to suffer." This statement was also made bythe Buddha. Please don't think that because youare unhappy, because there is pain in your heart,that you cannot go to the Buddha. It is exactlybecause there is pain in your heart thatcommunication is possible. Your suffering and mysuffering are the basic condition for us to enter theBuddha's heart, and for the Buddha to enter ourhearts.For forty-five years, the Buddha said, over andover again, "I teach only suffering and thetransformation of suffering." When we recognizeand acknowledge our own suffering, the Buddha —

which means the Buddha in us — will look at it,discover what has brought it about, and prescribe acourse of action that can transform it into peace,joy, and liberation. Suffering is the means theBuddha used to liberate himself, and it is also themeans by which we can become free.The ocean of suffering is immense, but if youturn around, you can see the land. The seed ofsuffering in you may be strong, but don't wait untilyou have no more suffering before allowingyourself to be happy. When one tree in the gardenis sick, you have to care for it. But don't overlookall the healthy trees. Even while you have pain inyour heart, you can enjoy the many wonders oflife — the beautiful sunset, the smile of a child, themany flowers and trees. To suffer is not enough.Please don't be imprisoned by your suffering.If you have experienced hunger, you know thathaving food is a miracle. If you have suffered fromthe cold, you know the preciousness of warmth.When you have suffered, you know how toappreciate the elements of paradise that arepresent. If you dwell only in your suffering, youwill miss paradise. Don't ignore your suffering, butdon't forget to enjoy the wonders of life, for your

sake and for the benefit of many beings.When I was young, I wrote this poem. Ipenetrated the heart of the Buddha with a heartthat was deeply wounded.My youthan unripe plum.Your teeth have left their marks on it.The tooth marks still vibrate.I remember always,remember always.Since I learned how to love you,the door of my soul has been left wide opento the winds of the four directions.Reality calls for change.The fruit of awareness is already ripe,and the door can never be closed again.Fire consumes this century,and mountains and forests bear its mark.The wind howls across my ears,while the whole sky shakes violently in thesnowstorm.Winter's wounds lie still,

Missing the frozen blade,Restless, tossing and turningin agony all night.11 "The Fruit of Awareness Is Ripe," in Call MeBy My True Names: The Collected Poems of ThickNhat Hanh (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1993), p. 59.I grew up in a time of war. There wasdestruction all around — children, adults, values, awhole country. As a young person, I suffered a lot.Once the door of awareness has been opened, youcannot close it. The wounds of war in me are stillnot all healed. There are nights I lie awake andembrace my people, my country, and the wholeplanet with my mindful breathing.Without suffering, you cannot grow. Withoutsuffering, you cannot get the peace and joy youdeserve. Please don't run away from yoursuffering. Embrace it and cherish it. Go to theBuddha, sit with him, and show him your pain. Hewill look at you with loving kindness, compassion,and mindfulness, and show you ways to embraceyour suffering and look deeply into it. Withunderstanding and compassion, you will be able toheal the wounds in your heart, and the wounds in

the world. The Buddha called suffering a HolyTruth, because our suffering has the capacity ofshowing us the path to liberation. Embrace yoursuffering, and let it reveal to you the way to peace.

CHAPTER TWOThe First Dharma TalkSiddhartha Gautama was twenty-nine years oldwhen he left his family to search for a way to endhis and others' suffering. He studied meditationwith many teachers, and after six years of practice,he sat under the bodhi tree and vowed not to standup until he was enlightened. He sat all night, and asthe morning star arose, he had a profoundbreakthrough and became a Buddha, filled withunderstanding and love. The Buddha spent the nextforty-nine days enjoying the peace of hisrealization. After that he walked slowly to theDeer Park in Sarnath to share his understandingwith the five ascetics with whom he had practicedearlier.When the five men saw him coming, they feltuneasy. Siddhartha had abandoned them, theythought. But he looked so radiant that they couldnot resist welcoming him. They washed his feetand offered him water to drink. The Buddha said,"Dear friends, I have seen deeply that nothing canbe by itself alone, that everything has to inter-bewith everything else. I have seen that all beings are

endowed with the nature of awakening." Heoffered to say more, but the monks didn't knowwhether to believe him or not. So the Buddhaasked, "Have I ever lied to you?" They knew thathe hadn't, and they agreed to receive his teachings.The Buddha then taught the Four Noble Truthsof the existence of suffering, the making ofsuffering, the possibility of restoring well-being,and the Noble Eightfold Path that leads to wellbeing. Hearing this, an immaculate vision of theFour Noble Truths arose in Kondanñña, one of thefive ascetics. The Buddha observed this andexclaimed, "Kondañña understands! Kondaññaunderstands!" and from that day on, Kondaññawas called "The One Who Understands."The Buddha then declared, "Dear friends, withhumans, gods, brahmans, monastics, and maras1 aswitnesses, I tell you that if I have not experienceddirectly all that I have told you, I would notproclaim that I am an enlightened person, free fromsuffering. Because I myself have identifiedsuffering, understood suffering, identified thecauses of suffering, removed the causes ofsuffering, confirmed the existence of well-being,obtained well-being, identified the path to well-

being, gone to the end of the path, and realizedtotal liberation, I now proclaim to you that I am afree person." At that moment the Earth shook, andthe voices of the gods, humans, and other livingbeings throughout the cosmos said that on theplanet Earth, an enlightened person had been bornand had put into motion the wheel of the Dharma,the Way of Understanding and Love. This teachingis recorded in the Discourse on Turning the Wheelof the Dharma (Dhamma Cakka PavattanaSutta).2 Since then, two thousand, six hundredyears have passed, and the wheel of the Dharmacontinues to turn. It is up to us, the presentgeneration, to keep the wheel turning for thehappiness of the many.1 See footnote number 7 on p. 17.2 Samyutta Nikaya V, 420. See p. 257 for thefull text of this discourse. See also the GreatTurning of the Dharma Wheel (Taisho RevisedTripitaka 109) and the Three Turnings of theDharma Wheel (Taisho 110). The term "discourse"(sutra in Sanskrit, sutta in Pali) means a teachinggiven by the Buddha or one of his enlighteneddisciples.

Three points characterize this sutra. The first isthe teaching of the M iddle Way . The Buddhawanted his five friends to be free from the idea thatausterity is the only correct practice. He hadlearned firsthand that if you destroy your health,you have no energy left to realize the path. Theother extreme to be avoided, he said, is indulgencein sense pleasures — being possessed by sexualdesire, running after fame, eating immoderately,sleeping too much, or chasing after possessions.The second point is the teaching of the FourNoble Truths. This teaching was of great valueduring the lifetime of the Buddha, is of great valuein our own time, and will be of great value formillennia to come. The third point is engagement inthe world. The teachings of the Buddha were notto escape from life, but to help us relate toourselves and the world as thoroughly as possible.The Noble Eightfold Path includes Right Speechand Right Livelihood. These teachings are forpeople in the world who have to communicatewith each other and earn a living.T h e Discourse on Turning the Wheel of theDharma is filled with joy and hope. It teaches usto recognize suffering as suffering and to transform

our suffering into mindfulness, compassion, peace,and liberation.

CHAPTER THREEThe Four Noble TruthsAfter realizing complete, perfect awakening(samyak sambodhi), the Buddha had to find wordsto share his insight. He already had the water, buthe had to discover jars like the Four Noble Truthsand the Noble Eightfold Path to hold it. The FourNoble Truths are the cream of the Buddha'steaching. The Buddha continued to proclaim thesetruths right up until his Great Passing Away(mahaparinirvana).The Chinese translate Four Noble Truths as"Four Wonderful Truths" or "Four Holy Truths."Our suffering is holy if we embrace it and lookdeeply into it. If we don't, it isn't holy at all. Wejust drown in the ocean of our suffering. For"truth," the Chinese use the characters for "word"and "king." No one can argue with the words of aking. These Four Truths are not something to argueabout. They are something to practice and realize.T he First Noble Truth is suffering (dukkha).The root meaning of the Chinese character forsuffering is "bitter." Happiness is sweet; suffering

is bitter. We all suffer to some extent. We havesome malaise in our body and our mind. We haveto recognize and acknowledge the presence of thissuffering and touch it. To do so, we may need thehelp of a teacher and a Sangha, friends in thepractice.T he Second Noble Truth is the origin, roots,nature, creation, or arising (samudaya) of suffering.After we touch our suffering, we need to lookdeeply into it to see how it came toThe Four Noble Truths & the NobleEightfold Path

Figure Onebe. We need to recognize and identify thespiritual and material foods we have ingested thatare causing us to suffer.T h e Third Noble Truth is the cessation(nirodha) of creating suffering by refraining fromdoing the things that make us suffer. This is goodnews! The Buddha did not deny the existence ofsuffering, but he also did not deny the existence of

joy and happiness. If you think that Buddhismsays, "Everything is suffering and we cannot doanything about it," that is the opposite of theBuddha's message. The Buddha taught us how torecognize and acknowledge the presence ofsuffering, but he also taught the cessation ofsuffering. If there were no possibility of cessation,what is the use of practicing? The Third Truth isthat healing is possible.T he Fourth Noble Truth is the path (marga)that leads to refraining from doing the things thatcause us to suffer. This is the path we need themost. The Buddha called it the Noble EightfoldPath. The Chinese translate it as the "Path of EightRight Practices": Right View, Right Thinking,Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood,Right Diligence, Right M indfulness, and RightConcentration.11 The Pali word for "Right" is samma and theSanskrit word is samyak. It is an adverb meaning"in the right way," "straight," or "upright," notbent or crooked. Right M indfulness, for example,means that there are ways of being mindful that areright, straight, and beneficial. Wrong mindfulnessmeans that there are ways to practice that are

wrong, crooked, and unbeneficial. Entering theEightfold Path, we learn ways to practice that areof benefit, the "Right" way to practice. Right andwrong are neither moral judgments nor arbitrarystandards imposed from outside. Through our ownawareness, we discover what is beneficial ("right")and what is unbeneficial ("wrong").

CHAPTER FOURUnderstanding the Buddha's TeachingsWhen we hear a Dharma talk or study a sutra,our only job is to remain open. Usually when wehear or read something new, we just compare it toour own ideas. If it is the same, we accept it andsay that it is correct. If it is not, we say it isincorrect. In either case, we learn nothing. If weread or listen with an open mind and an open heart,the rain of the Dharma will penetrate the soil ofour consciousness.11 According to Buddhist psychology, ourconsciousness is divided into eight parts, includingmind consciousness (manovijñana) and storeconsciousness (alayavijñana). Store consciousnessis described as a field in which every kind of seedcan be planted — seeds of suffering, sorrow, fear,and anger, and seeds of happiness and hope. Whenthese seeds sprout, they manifest in our mindconsciousness, and when they do, they becomestronger. See fig. 5 on p. 208.The gentle spring rain permeates the soil of mysoul.

A seed that has lain deeply in the earth for manyyears justsmiles)22FromThich Nhat Hanh, "CuckooTelephone," in Call Me By My True Names, p.176.While reading or listening, don't work too hard.Be like the earth. When the rain comes, the earthonly has to open herself up to the rain. Allow therain of the Dharma to come in and penetrate theseeds that are buried deep in your consciousness.A teacher cannot give you the truth. The truth isalready in you. You only need to open yourself —body, mind, and heart — so that his or herteachings will penetrate your own seeds ofunderstanding and enlightenment. If you let thewords enter you, the soil and the seeds will do therest of the work.The transmission of the teachings of theBuddha can be divided into three streams: SourceBuddhism, M any-SchoolsBuddhism, and

M ahayana Buddhism. Source Buddhism includesall the teachings the Buddha gave during hislifetime. One hundred forty years after theBuddha's Great Passing Away, the Sangha dividedintotwo s c h o o l s : Mahasanghika (literally"majority," referring to those who wanted changes)a n d Sthaviravada (literally, "School of Elders,"referring to those who opposed the changesadvocated by the M ahasanghikas). A hundredyears after that, the Sthaviravada divided into twobranches— Sarvastivada ("the School thatProclaims Everything Is") and Vibhajyavada ("theSchool that Discriminates"). The Vibhajyavadins,supported by King Ashoka, flourished in theGanges valley, while the Sarvastivadins went northto Kashmir.For four hundred years during and after theBuddha's lifetime, his teachings were transmittedonly orally. After that, monks in the TamrashatiyaSchool ("those who wear copper-colored robes") inSri Lanka, a derivative of the Vibhajyavada School,began to think about writing the Buddha'sdiscourses on palm leaves, and it took anotherhundred years to begin. By that time, it is said thatthere was only one monk who had memorized thewhole canon and that he was somewhat arrogant.

The other monks had to persuade him to recite thediscourses so they could write them down. Whenwe hear this, we feel a little uneasy knowing thatan arrogant monk may not have been the bestvehicle to transmit the teachings of the Buddha.Even during the Buddha's lifetime, there werepeople such as the monk Arittha, whomisunderstood the Buddha's teachings andconveyed them incorrectly. 3 It is also apparentthat some of the monks who memorized the sutrasover the centuries did not understand their deepestmeaning, or at the very least, they forgot orchanged some words. As a result, some of theBuddha's teachings were distorted even before theywere written down. Before the Buddha attainedfull realization of the path, for example, he hadtried various methods to suppress his mind, andthey did not work. In one discourse, he recounted:3 Arittha Sutta (Discourse on Knowing theBetter Way to Catch a Snake), Majjhima Nikaya22. See Thich Nhat Hanh, Thundering Silence:Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Catch a Snake(Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1993), pp. 47-49.I thought, Why don't I grit my teeth, press my

tongue against my palate, and use my mind torepress my mind? Then, as a wrestler might takehold of the head or the shoulders of someoneweaker than he, and, in order to restrain and coercethat person, he has to hold him down constantlywithout letting go for a moment, so I gritted myteeth, pressed my tongue against my palate, andused my mind to suppress my mind. As I did this,I was bathed in sweat. Although I was not lackingin strength, although I maintained mindfulness anddid not fall from mindfulness, my body and mymind were not at peace, and I was exhausted bythese efforts. This practice caused other feelings ofpain to arise in me besides the pain associated withthe austerities, and I was not able to tame mymind.44 Mahasaccaka Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya 36.Obviously, the Buddha was telling us not topractice in this way. Yet this passage was laterinserted into other discourses to convey exactlythe opposite meaning:Just as a wrestler takes hold of the head or theshoulders of someone weaker than himself,restrains and coerces that person, and holds him

down constantly, not letting go for one moment, soa monk who meditates in order to stop allunwholesome thoughts of desire and aversion,when these thoughts continue to arise, should grithis teeth, press his tongue against his palate, anddo his best to use his mind to beat down and defeathis mind.55 Vitakka Santhana Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya 20.This same passage was inserted into a Sarvastivadaversion of the Buddha's discourse on mindfulness,Nian Chu Jing, Madhyama Agama 26, TaishoRevised Tripitaka.Often, we need to study several discourses andcompare them in order to understand which is thetrue teaching of the Buddha. It is like stringingprecious jewels together to make a necklace. If wesee each sutra in light of the overall body ofteachings, we will not be attached to any oneteaching. With comparative study and lookingdeeply into the meaning of the texts, we cansurmise what is a solid teaching that will help ourpractice and what is probably an incorrecttransmission.By the time the Buddha's discourses were

written down in Pali in Sri Lanka, there wereeighteen or twenty schools, and each had its ownrecension of the Buddha's teachings. These schoolsdid not tear the teachings of the Buddha apart butwere threads of a single garment. Two of theserecensions exist today: the Tamrashatiya andSarvastivada canons. Recorded at about the sametime, the former was written down in Pali and thelatter in Sanskrit and Prakrit. The sutras that werewritten down in Pali in Sri Lanka are known as theSouthern transmission, or "Teachings of theElders " (Theravada). The Sarvastivada texts,known as the Northern transmission, exist only infragmented form. Fortunately, they were translatedinto Chinese and Tibetan, and many of thesetranslations are still available. We have toremember that the Buddha did not speak Pali,Sanskrit, or Prakrit. He spoke a local dialect calledM agadhi or Ardhamagadhi, and there is no recordof the Buddha's words in his own language.By comparing the two extant sutra recensions,we can see which teachings must have precededBuddhism's dividing into schools. When the sutrasof both transmissions are the same, we canconclude that what they say must have been therebefore the division. When the recensions are

different, we can surmise that one or both might beincorrect. The Northern transmission preservedsome discourses better, and the Southerntransmission preserved others better. That is theadvantage of having two transmissions to compare.The third stream of the Buddha's teaching,M ahayana Buddhism, arose in the first or secondcentury B.C.E.6 In the centuries following theBuddha's life, the practice of the Dharma hadbecome the exclusive domain of monks and nuns,and laypeople were limited to supporting theordained Sangha with food, shelter, clothing, andmedicine. By the first century B.C.E., manymonks and nuns seemed to be practicing only forthemselves, and reaction was inevitable. The idealput forth by the M ahayanists was that of thebodhisattva, who practiced and taught for thebenefit of everyone.6 See Thich Nhat Hanh, Cultivating the Mind ofLove: The Practice of Looking Deeply in theMahayana Buddhist Tradition (Berkeley: ParallaxPress, 1996).These three streams complement one another. Itwas impossible for Source Buddhism to remember

everything the Buddha had taught, so it wasnecessaryfor M any-Schools Buddhism andM ahayana Buddhism to renew teachings that hadbeen forgotten or overlooked. Like all traditions,Buddhism needs to renew itself regularly in orderto stay alive and grow. The Buddha always foundnew ways to express his awakening. Since theBuddha's lifetime, Buddhists have continued toopen new Dharma doors to express and share theteachings begun in the Deer Park in Sarnath.Please remember that a sutra or a Dharma talk isnot insight in and of itself. It is a means ofpresenting insight, using words and concepts.When you use a map to get to Paris, once you havearrived, you can put the map away and enjoy beingin Paris. If you spend all your time with your map,if you get caught by the words and notionspresented by the Buddha, you'll miss the reality.The Buddha said many times, "M y teaching is likea finger pointing to the moon. Do not mistake thefinger for the moon."In the M ahayana Buddhist tradition, it is said,"If you explain the meaning of every word andphrase in the sutras, you slander the Buddhas ofthe three times — past, present, and future. But if

you disregard even one word of the sutras, yourisk speaking the words of M ara."7 Sutras areessential guides for our practice, but we must readthem carefully and use our own intelligence and thehelp of a teacher and a Sangha to understand thetrue meaning and put it into practice. After readinga sutra or any spiritual text, we should feel lighter,not heavier. Buddhist teachings are meant toawaken our true self, not merely to add to ourstorehouse of knowledge.7 M ara: the Tempter, the Evil One, the Killer,the opposite of the Buddha nature in each person.Sometimes personalized as a deity.From time to time the Buddha refused toanswer a question posed to him. The philosopherVatsigotra asked, "Is there a self?" and the Buddhadid not say anything. Vatsigotra persisted, "Doyou mean there is no self?" but the Buddha still didnot reply. Finally, Vatsigotra left. Ananda, theBuddha's attendant, was puzzled. "Lord, youalways teach that there is no self. Why did you notsay so to Vatsigotra?" The Buddha told Anandathat he did not reply because Vatsigotra waslooking for a theory, not a way to remove

obstacles.8 On another occasion, the Buddha hearda group of disciples discussing whether or not hehad said such and such, and he told them, "Forforty-five years, I have not uttered a single word."He did not want his disciples to be caught bywords or notions, even his own.8 Samyutta Nikaya XIV, 10.When an archaeologist finds a statue that hasbeen broken, he invites sculptors who specialize inrestoration to study the art of that period andrepair the statue. We must do the same. If we havean overall view of the teachings of the Buddha,when a piece is missing or has been added, we haveto recognize it and repair the damage.

CHAPTER FIVEIs Everything Suffering?If we are not careful in the way we practice, wemay have the tendency to make the words of ourteacher into a doctrine or an ideology. Since theBuddha said that the First Noble Truth is

means by which we can become free. The ocean of suffering is immense, but if you turn around, you can see the land. The seed of suffering in you may be strong, but don't wait until you have no more suffering before allowing yourself to be happy. When one tree in the garden is sick, you have