Transcription

Education Development Center, Inc.Developing Rehabilitation Assistance to Schools and Teacher Improvement (D-RASATI) ProjectEchmoun Building, 8th floor, Damascus Road, Sodeco - BeirutT: 961 1 324 331M: 961 71 512 307/8F: 961 1 328 331E: info@d-rasati.orgTECHNOLOGY TEACHING AND LEARNINGRESEARCH, EXPERIENCE, & GLOBAL LESSONS LEARNED

Mary Burns, Education Development CenterThanks to the following MEHE and CERD colleagues in Lebanon for their input,review, and guidance of this document:Paulette Assaf: Project Manager, Institutional Development & ICT, Ministry ofEducation and Higher Education, Beirut, LebanonDr. Wafa Kotob: Education Policy and Planning Specialist, Ministry of Educationand Higher Education, Beirut, LebanonElham Komaty: Education Leadership and Management Specialist, Ministry ofEducation and Higher Education, Beirut, LebanonGizelle Faddoul: Head of Educational Installations and Aids Bureau - Center ForEducational Research and Development, Beirut, LebanonSamya Abou Hamad: Head Of English Department - Center For EducationalResearch and Development , Beirut, LebanonAbdo Yammine: Coordinator of all Educational Projects using ICT, Ministry ofEducation & Higher Education, Beirut, LebanonToufic Karam: IT Director, Ministry of Education and Higher Education, BeirutMadeleine El Helou: Administrative and Finance Assistant, Ministry of Education& Higher Education, Beirut, LebanonThanks to EDC and D-RASATI colleagues for their input, guidance and review ofthis document:Daniel Light, Research Scientist, Center for Children and Technology at EducationDevelopment Center, New York, NYSusan Ross, Deputy Chief of Party, USAID-funded D-RASATI Project, Beirut,LebanonThis study is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the UnitedStated Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility ofEducation Development Center, Inc. (EDC) and do not necessary reflect the views of USAID orthe United States Government.

TableOf Contents03. Using Technology for Teaching and Learning: Best Practices Introduction and Overview01.Educational Technology in Lebanon, Jordan, the United Kingdom,and the United States LebanonJordanUnited KingdomUnited States02. Technologies for Teaching and Learning Computer-based productivity applicationsVisually-based applications and technologiesInternet-based applications and technologiesMultimedia applicationsMobile technologiesAssistive technologiesSummaryTechnology must be one part in a larger system of educational reformDevelop a vision of how technology should be usedDevelop a shared language about teaching, learning and technologyDevelop a comprehensive national ICT in education policy with a designed focusDefine and promote the roles of multiple stakeholdersAlign national and school goals and expectations around the use of technology for teaching and learningChange the teacher evaluation system to reflect technology integration supported bylearner-centered instruction and assessmentEnsure classroom access to technologyDevelop standards for quality educationBuild strong leadershipRecruit, hire and continually train high-quality teachersProvide teachers with a variety of different types of high-quality professional developmentIntegrate technology into the curriculum by helping teachers with instructional designIncentivize teacher use of technology to support learner-centered instructionProvide teachers with ongoing supportsBuild reliable, valid and rigorous evaluation terviews129Lebanese Sources of Information130Glossary of Terms131

In much of the globe,classroom technology hasbecome as common placeas the chalkboard, bookand pencil it now replaces.This is increasingly truein many classrooms in thewealthiest nations ofthe world.For the young men at the King’s Academy in Jordan, PC tablets withstyluses have largely replaced pencils and notebooks. In British schools,children with severe learning disabilities interact with the world aroundthem via immersive environments that enable them to carry out onscreenphysical tasks that would be impossible off-screen. Students in remotesheep stations of the Australian “outback” access their teacher in faraway Darwin or Perth via two-way audio and Internet-enabled interactivewhiteboards. In Singapore, science students construct and programrobots—while in 20 kindergartens in South Korea, robots teach youngchildren English. More prosaically, for a plurality of high-school andmiddle-school students in North America and Europe, pencil-and-paperreports and homework have given way to word-processed reports andstudents seek help from their teachers after school hours via email.The proliferation of technology for teaching and learning (“instructional”or “educational technology”) begs a number of obvious questions: Howcan technologies impact teaching and learning? Are all applications andtechnologies “equal” in this regard or are some “better” than others? Whatactions should educational policymakers and planners undertake to makesure technology improves teaching and learning? And perhaps, most basic ofall—does educational technology really improve student learning?This monograph addresses such questions by examining the use ofinstructional technologies in Lebanon, the US, Jordan and Britain. Thehope is that readers will emerge with a stronger sense of clarity aboutwhat and how various technologies (defined here as platform-based) andapplications (defined in this monograph as a computer program or typeof software) may positively impact student learning—and what policies,plans and procedures are necessary to enable successful classroomdesign and implementation. Section 1 provides an overview of educationaltechnology in Lebanon, Jordan, Britain and the United States. Section2 outlines common classroom technologies, examples of their use forteaching and learning, and notes the research findings on a number ofthese tools. Section 3 assembles the best practices and pre-requisitesfrom these nations (and others) to begin to design the contours of asystem that effectively integrates technology into the teaching and learningprocess. Because technology terminology is often ill-defined, contradictory,redundant, or just plain confusing (even for those in the field), thismonograph is accompanied by a glossary of terms, included as Annex 1.1The US was selected because of its long history in the use of instructional technology; Jordan was chosen because of its proximity to Lebanon, its sharedcharacteristics and its systematic approach to instructional technology; and the United Kingdom included because of its comprehensive focus on providingtechnology to all schools. The reader should note that both the amount and quality of research is variable among the three nations, and some of itunavailable to the author because of language limitations.

“Educational technology” or“Information and CommunicationsTechnologies (ICTs)” comprisenot just computers or the Internet.They may include such diversetools as videoconferencing, digitaltelevision, electronic whiteboards,and gaming. Increasingly ICTs notonly include small, portable devicessuch as tablets, MP3 players,gaming devices, and Smart- and cellphones, but have in fact become smallportable devices—a trend that willcertainly continue.As we move to a discussionof whether, how and whattechnologies can impact teachingand learning, two observations,both of which will frame theremainder of this monograph, areworth noting.The research regardingtechnology’s impact is variable:Thousands of comparisonsbetween “computing and noncomputing” classrooms havebeen made since the late 1960sand scores of meta-analysesaround technology and studentlearning have been undertakensince 1980 (Tamim, Bernard,Borokhovski, Abrami, & Schmid,2011:2), yet the overall quality ofresearch remains variable. Someof this research may be regardedas “high quality”—using controlgroups, probabilistic sampling,reliable and sensitive instrumentsand measures, or qualitativelyrich case designs; and controllingfor “confounding” influenceslike maturation or noveltyeffects. Much more researchis methodologically suspect,descriptive or anecdotal. Thoughthis review aims to cull informationfrom more “rigorous” empiricalresearch2 outlining how certaintechnologies and applications canbe used optimally for teachingand learning, we cannot vouch forthe quality of this research. Eachtype of technology, as this reviewwill illustrate, offers its share ofbenefits and drawbacks.suggests three conditional, promising outcomes vis-à-vis technology’simpact on student learning:Despite all research data, thereis no longitudinal, irrefutablebody of evidence that states thatcomputers alone improve learning.Many highly-touted applicationsand software show no “measurableimpact” on or “no significantdifference” in student learning,and indeed, much researchdemonstrates negative impacts oftechnology on student learning.1. Technology can compensate for poor teacher quality: An increasingbody of research demonstrates that exposure to ICTs may increasethe cognitive abilities of students, allowing them to learn faster. This isparticularly true in contexts where teacher quality is poor (Carillo, Onofa& Ponce, 2010:2; Banerjee & Duflo, 2011) (See Figure 1).And research does not exist forall technologies. For many newertypes of technologies, suchas Smart Phones and tablets,despite the evident excitementand promise, there is little or noresearch proving their worth asteaching and learning tools.3. Technology is most successful when part of an overall focus onthe key components of teaching and learning: The dominant themethat emerges from technology in education is that content, instruction,assessment and sound policies, practices and support matter far morethan the kind of laptop, the software suite or whether or not teachers canmake a spreadsheet (Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, 2009;Tamim et al., 2011). As research and experience inform us, technology“works” when it supports intended learning outcomes and when it is usedto deepen content knowledge, instruction and assessment. Successfuluse of technology—helping students learn in ways are measurablybetter or that would otherwise be impossible—still depends, not onboxes, bandwidth or wires, but on that most fundamental classroomtransaction—good instruction.2. Technology can benefit special populations: Research increasinglyand cumulatively suggests that under certain conditions, technology canpromote small to moderate gains in student learning (Tamim, et al., 2011),especially for learners with special needs (Ofsted, 2009) and for preschool learners in terms of early literacy3 (Penuel et al., 2009).Under Certain ConditionsTechnology Demonstrates PositiveBenefits: However, despite suchseeming pessimism, there is anincreasing body of research thatSuch as first- and second-order meta-analyses. A first-order meta-analysis analyzes findings across several primary evaluations/studies that addressa set of related research hypotheses and reports measures as an effect size. A second-order meta-analysis summarizes findings of meta-analyses, overa number of years, in the same way that a meta-analysis attempts to reach more reliable and generalizable inferences than individual primary studies(Peterson, 2001, cited in Tamim, et al. 2011).2Figure 1: The Impact of Technology in Poor vs.Wealthy Nations (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011: 100)“Current research on educational technology’s impact on studentlearning is mixed—but most of the research comes from “rich” nationswhere the alternative to being taught by a teacher is being taught by ahighly-motivated and highly-qualified teacher. In poor countries, andin poor regions of moderately well-off nations where teacher quality islow, the evidence on the effectiveness of computer assisted programsversus teachers, though sparse, is quite positive. Research in India, forexample, showed that children who played a computer math gametwo hours per week had learning gains as large as some of the mostsuccessful educational innovations tried over the years.”One such study was the Ready to Learn Evaluation, an efficacy study that examined the impact of combining repeated home viewing of clips from twoeducational television programs for children (Sesame Street and Between the Lions) with interactive literacy activities for parents to use with children.3

Educational Technologyin Lebanon, Jordan,the United Kingdom,and the United StatesAcross the globe, various nations have made strides inintegrating technology into their educational system.This section examines four such efforts—from Lebanon,Jordan, the United Kingdom (Britain), and the UnitedStates—discussing their overall stages of educationaltechnology development and implementation. Tobetter situate the educational technology experiencesof these four cases, Figure 2 presents a continuum ofcharacteristics that categorize these national effortsas “emerging,” “trialling,” and “achieving” in termsof overall educational technology indicators—policy,provision of technology in schools, the focus of ICTefforts, integration into the curriculum, teacher training,attitudes toward ICT, funding, and supports. Ourdiscussion of each nation’s educational technologyefforts will reference this matrix.01.

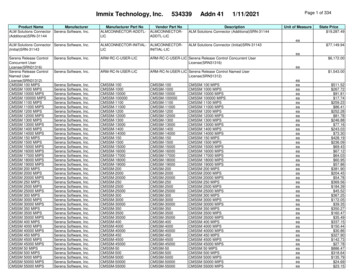

Educational Technology in Lebanon, Jordan, the United Kingdom,01. EducationalTechnologyand the UnitedStates in Lebanon, Britain, Jordan and the United StatesFigure 2: Stages of Educational Technology Implementation (Adapted from UNESCO Bangkok, 2006; Yuen 2000)TraitICT PolicyICT ProvisionEmergingHave national policies but noplans for implementation, orhave no national policies andonly undertake small scaleand ad hoc ICT projectsConstrained by costs andthe lack of computers andInternet accessThere may be schools withICTs but typically theseschools have securedequipment and connectivitythrough their own initiative,through private donations oras part of a pilot activityTriallingNational ICT in educationpolicies are linked tonational ICT policiesICT penetration, connectionand bandwidth are variableand development isconstrained by costs andlogisticsICT integration is neithersystemic nor nationwideAchievingMinistries of Educationhave set national e-learningpolicies and plans andprovided adequate budget forimplementationICT integration is systemic—technology is present inall schools and all typesof schools throughout thecountryTechnological adoptionmodel: Emphasis is onproviding hardware, software,infrastructure, connectivity,and curriculum resources.Change in educationalpractice is minimal at bestCatalytic integrationmodel: Emphasis is on staffdevelopment. There is somechange in curriculum andpedagogical reform.Cultural integration model:Emphasis is on cultural andorganizational change. Thisis the approach that achievesthe most significant change.ICT in the CurriculumTreat ICT as a subject or anoptional or extra-curricularactivity, rather thanembedding it in subjectlearningICT is treated as a subjectin its own right andteachers mainly use ICTfor productivity (wordprocessing, spreadsheetsand classroom presentationof information)Curricula are being revisedto exploit e-learningICTs are woven intocontent-area instructionand/ or are used as aparallel delivery system ofeducation (such as onlineLearning )Since ICT is a separatesubject area, ICT skills areassessed separately, withinIT classesSome movementtoward computer-basedassessment or computerembedded assessmentbut most assessment isstill “paper-based”Use of computer-based,computer-embeddedand computer adaptedassessment systemsNo reflection of ICT-relatedskills or knowledge in theoverall assessment systemLack of computer-basedor computer-embeddedassessment10Movement towardassessing students’practical ICT knowledgeand skills within aparticular content area(for example, studentsmust display a particularmath concept usingspreadsheets)Teacher TrainingEmergingOff-the-job training (i.e., innon-school locations)Limit teachers’ training to ICTskills developmentThere are high levels ofcomputer provision andInternet connectivity and lowstudent-computer ratios inclassroomsFocus of ICT EffortsAssessing ICTsTraitNo follow-up supportLeadership and ICTTeachers and principals areunaware of how to use ICTsfor teaching and learningTriallingOff the job training but withlimited on-the-job trainingat timesLimit teachers’ training toICT skills development, ICTfor teacher productivity andperhaps some strategiesfor classroom integrationof ICTsAchievingPrimarily on the jobAdministrators,headmasters andteachers receivetraining (increasinglyonline) not only in ICTskills but in e-learning,website development,telecollaboration, etc.No or limited follow-upsupportOngoing follow-up supportMany principals are curious(but unsure of what to do)apathetic or antagonistictoward ICT in the classroomTeachers and administratorsare generally positive aboutICTs and understand howit can be used to supportteaching and learningTeachers may be fearful oftechnology, unconvinced ofits worth and slow to changetheir teaching methodsFundingMay be heavily dependenton international donorsand private companies fortechnology fundingMix of donor funding,government funding andprivate companies fortechnology fundingMainly government funding,with some private and publicphilanthropies and privatecompany funding for ICTsSupports for ICTsThere is a lack of technicalsupport, e-courseware andevaluation around ICTsThere is some technicalsupport, e-courseware andevaluation around ICTs.Where support exists, it isstill mainly offsite.Site-based technical support,e-courseware and evaluationaround ICTsPerformance indicators areused to monitor the impact ofICT in educationICT knowledge and skillsmay be one component ofthe overall set of skills andknowledge that is assessed(for example, as part ofoverall performance-basedassessment)Technology is a mediumfor content that is assessed(e.g., students are assessedvia persuasive essay but essaymust be word processed)11

Educational Technology in Lebanon, Jordan, the United Kingdom,01. EducationalTechnologyand the UnitedStates in Lebanon, Britain, Jordan and the United StatesMost ICT education efforts in Lebanon have focusedon securing access and connecting computers toteaching and learning““LebanonLebanon4 differs from the remaining three case sites in this monograph—Jordan,the United Kingdom and the United States—in that it is a post-conflict nationthat has had to focus on rebuilding institutions and structures following afifteen year civil war, and conflict in 2006. Given this reality, Lebanon’s overalleducational technology (or “ICT in education”) efforts may best be categorizedwithin the emerging category of nations in terms of the overall educationaltechnology efforts.Chronology of Educational TechnologyInitiatives in LebanonIn 2000, Lebanon launched its first “ICT in education” project, SchoolNetLiban. Similar to the national SchoolNets found in Africa, Latin America andEurope, Lebanon’s SchoolNet aimed to utilize technology to modernize theoverall education system by making instruction more relevant, improving thequality of educational content and introducing technology into the teaching andlearning system. Specifically, SchoolNet Liban’s overall objectives were manifold:to facilitate effective learning for Lebanese students; foster life-long learning anda “knowledge-based society;” enhance the capacity of teachers to teach withtechnology; create a national educational network for Lebanese teachers andstudents to develop and showcase ICT projects (which has basically becomeover time the main objective of the project); and to provide linkages and onlinecollaboration opportunities for students and teachers with their peers across theglobe (Yammine, personal communication, September 13, 2011).Formally, Lebanon initiated its educational technology strategy beginningin 2000. In 2007, the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE)launched an educational vision document. In alignment with this educationalvision, MEHE has begun to develop a centralized, national educationaltechnology strategy, as well as the requisite supporting systems and documentsto carry out the components of such a strategy.Technology is not widespread in most Lebanese government schools. Mosteducational technology initiatives have been funded by private technologycompanies or initiatives such as SchoolNet Liban (to be discussed momentarily).Technology provision and Internet connectivity are major impedimentsto and therefore a major focus of large-scale national ICT initiatives. Thecurriculum, which in 2011 began revision by grade-level cycle, has not yetbeen modified to support the use of ICTs. The student assessment systemhas not yet been modified to reflect the new curriculum or technology thoughsuch efforts will most likely be undertaken in the next several years (Fayad,personal communication, September 12, 2011). The efforts of the past decadehave essentially focused on a “technology adoption model” emphasizingaccess—the provision of hardware, software, connectivity and resources. Atpresent, there is little coordinated school-based support for teachers to useICT and most technology use in Lebanese schools occurs in computer labsas part of information technology (IT classes). However, these issues will beaddressed through the adoption and implementation of Lebanon’s 2012 nationaleducational technology strategy.Since its inception, SchoolNet Liban has been an enduring fixture in the Lebaneseeducational technology landscape. Since 2002, when it began in 12 publicschools, it has expanded to 105 public schools as of 2011, with an overall goal ofengaging 200 schools by 2012, which would give it a presence in approximately14 percent of Lebanese schools. SchoolNet Liban has partnered with a number oftechnology companies such as Intel, Cisco, Promethean, and Microsoft and withnon-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Educational Associationfor IT Development (EAITD) and Interactive Education Technology (IET). Eachyear, Lebanese students participate in regional SchoolNet competitions withprizes for winning projects.In October 2003, the Lebanese Government, through the United NationsDevelopment Programme (UNDP) and the Office of the Minister of State forAdministrative Reform (OMSAR), completed the development of the “Nationale-Strategy.” The vision was aimed at “moving the economy and society of512See http://www.lebanonpartnership.org/13

Educational Technology in Lebanon, Jordan, the United Kingdom,01. EducationalTechnologyand the UnitedStates in Lebanon, Britain, Jordan and the United StatesMost ICT in education efforts in Lebanon havefocused on one of two areas““Lebanon toward a knowledge-based society in the shortest possible time whileat the same time addressing related challenges and opportunities that Lebanonis facing” (United Nations, 2007:5). Thirty-two policies, grouped under seveninitiatives, were proposed as vehicles for implementing the strategy. A portal(http://www.e-gateway.gov.lb) was designed and developed to incorporate allinformation and data pertaining to the various initiatives that are related to theproject.Figure 3: Overview of Major Private Sector ICT for Education Initiatives in Lebanon (Source: Organizations listed in this table8)Organizationand PartnersMicrosoft – IEAD(2002- 2011)ProjectName/Typeof AssistancePartners in Learning:Innovative StudentsFoster life-long learning to foster greater movementtoward a “knowledge-based society”SchoolNet LibanEnhance the capacity of teachers to teach withtechnologyMost ICT in education efforts in Lebanon have focused on one of two areas.The first are initiatives6 that focus on securing access (through provision ofhardware, software, or connectivity) for teachers and students. The second areefforts to connect computer technology to teaching and learning through theprovision of learning opportunities to teachers, students or both. Since theselatter are smaller in scale, though of longer durations in some cases, they aredefined in this document as programs.TargetAudienceTeachers andstudents in 105schools6000 studentsCreate a national educational network for Lebaneseteachers and students to develop and showcase ICTprojectsAfter 2006, five US-based companies (Microsoft, Occidental Petroleum,Intel, Cisco, and Ghafari, Inc.) established the Partnership for Lebanon5 to aidin its reconstruction. Though not explicitly directed toward the promotion ofICTs in Lebanese society, many of its initiatives did in fact emphasize the roleof ICT. In part, through this partnership, technology companies have launchedICT in education efforts in 52 Lebanese public schools, teachers’ regional offices(centers for training) and exam centers.There have been a number of large-scale technology provisions for Lebaneseschools. As part of its Education Development Project for Lebanon, the WorldBank supplied and installed 2770 computers and peripherals (printers andfaxes) in 1385 intermediate and secondary public schools; nine schools havebeen equipped with 81 computers for 868 students; and 95 administrators atthe Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE), Center for EducationResearch and Development (CERD) and regional offices have been givencomputers to help them run daily administrative tasks (World Bank, 2010).Stated GoalsProvide linkages and online collaborationopportunities for students and teachers with theirpeers across the globePromote learning through discoveryUse ICT to acquire and share knowledgeImprove students’ communication, presentationand negotiation skillsIntel – HaririFoundation,YMCA(2005-2009)Intel Teach: TeacherprofessionaldevelopmentTrain teachers to effectively integrate technologyin classroom to enhance learning and build 21stcentury skills, and to shift from a teacher centricapproach to an interactive method focusing on thestudent6000 Teachers/TraineesPrepare students with 21st century learning skills,such as technology and digital literacy, effectivecommunication, critical thinking, problem solving,collaborationShare experiences among the participants ondifferent adopted approachesFigures 3 and 4 outline some of Lebanon’s major technology initiatives andprograms, implemented in coordination and collaboration with the Ministry ofEducation and Higher Education constituents and the Center for EducationalResearch and Development (CERD).5See � in this monograph are defined as large-scale attempts to establish availability and access, training or connectivity aroundtechnology as a foundation for greater general educational use. Many of Lebanon’s major technology initiatives have been spearheaded by technology companies.614Cisco’s IT Academies, which are really an extension of its networking initiative (which provided routers and switches as well as aTelepresence system to MEHE), are designed to develop capacity in networking skills and have thus been included in this table as anoverall adjunct to Cisco’s main networking initiative.715

01.Educational Technology in Lebanon, Jordan, the United Kingdom,and the United StatesOrganizationand PartnersProjectName/Typeof AssistanceMicrosoft(2005-2011)Partners in Learning:Innovative TeachersStated GoalsEnable MEHE to:Improve access to and use of information andcommunications technology (ICT) in primary andsecondary educationTargetAudienceOrganizationand PartnersProjectName/Typeof Assistance1937 teachers total(2005-2011)Stated GoalsTargetAudiencethe relevant directorates in the MEHEMake full use of this infrastructure for e-contentdevelopmentBridge the digital divide in public educationMicrosoft(June 2009 –present)Improve the teaching and communication skills ofeducators in public schoolsIncrease the use of ICT as an educational tool inpublic schoolsLive @EDUFacilitate alumni communicationImprove/facilitate communication among theMEHE, school administrators, faculty, parents andstudentsImprove access to, and the use of, ICT for thesupport of teaching and learning(2006)Arab ThoughtFoundation andIntel – Triple C(2006-2010)IT Academies7Building networkingcapacityIntroduce IT literacy into high schools and amongschool dropouts16 AcademiesBuild student networking capacityDigital Learningdissemination Distribution ofequipmentIntroduce Intel eLearning series solution toteachers, including Classmate PCs , and all softwareembedded within1120 IntelClassmates toStudentsInspire teachers to use Intel Learning Seriestechnology creatively and to help students acquireknowledge in a 1:1 e-Learning environment40 IntelClassmates toTeachersHelp teachers create student-centered lessonplans for instructional purposes to allow studentsto use Classmate PC’s integrated tools, embeddedsoftware, and associated online education materialsCisco – HaririFoundation, BMB(2008-2010)Lebanese NationalEducationalNetwork (LEBNEN) NetworkingEstablish a National Education Network using CiscoNetworks devices to connect all public high schoolsacross Lebanon5 pilot schools(reduction ofinitial target setfor all teachersand students inLebanon)Introduce ICT in the classroom and preparestudents for the futureLearn new concepts and best practicesCisco – HaririFoundationProvide cloud-based email; enterprise-class tools;online document sharing and storageWalid Bin Talal Promethean andIET(2010-2011)Interactive Boards(IWB): distributionof interactivewhiteboards(IWBs) and teacherprofessionaldevelopmentIntegrate ICT in education based on 21st centuryeducation strategies by using IWBs in theclassroomCompliance with “green” ICT through studentcentered learning and sharing digital content113 IWBs3600 teachersand educationleadersCreate one for all and all for one teacher’scommunity interactive lessons portal based on 21stcentury le

away Darwin or Perth via two-way audio and Internet-enabled interactive whiteboards. In Singapore, science students construct and program robots—while in 20 kindergartens in South Korea, robots teach young children English. More prosaically, for a plurality of high-school and middle-scho