Transcription

Grant, Robert M.The resource-based theory of competitiveadvantage: implications for strategyformulationGrant, Robert M., (1991) "The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategyformulation" from California Management Review 33 (3) pp.114-135, Berkeley, Calif.: University ofCalifornia Staff and students of Anglia Ruskin University are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and thework from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence whichallows you to:* access and download a copy;* print out a copy;Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study asstated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material andshould not download and/or print out a copy.This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of thisLicence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end ofthe course, but strictly for your own personal use.All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/ordeleted if and when required by Anglia Ruskin University.Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail)is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder.The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neitherstaff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or anyother derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author.This is a digital version of copyright material made under licence from the rightsholder, and its accuracycannot be guaranteed. Please refer to the original published edition.Licensed for use for the course: "Strategic Management Analysis".Digitisation authorised by Sarah PackardISSN: 0008-1256

114The Resource-Based Theoryof Competitive Advantage:Implications forStrategy FormulationRobert M. Granttrategy has been defined as "the match an organizationmakes between its internal resources and skills . . . andthe opportunities and risks created by its external environment."' During the 1980s, the principal developments instrategy analysis focussed upon the link between strategy andSthe external environment. Prominent examples of this focus are MichaelPorter's analysis of industry structure and competitive positioning and theempirical studies undertaken by the PlMS project. By contrast. the linkbetween strategy and the firm's resources and skills has suffered comparative neglect. Most research into the strategic implications of the firm'sinternal environment has been concerned with issues of strategy implementation and analysis of the organizational processes through whichstrategies emerge. 3Recently there has been a resurgence of interest in the role of the firm'sresources as the foundation for fi rm strategy. This interest reflects dissatisfaction with the static, equilibrium framework of industrial organizationeconomics that has dominated much contemporary thinking about businessstrategy and has renewed interest in older theories of profi t and competitionassociated with the writings of David Ricardo, Joseph Schumpeter, andEdith Penrose. Advances have occurred on several fronts. At the corporatestrategy level, theoretical interest in economies of scope and transactioncosts have focussed attention on the role of corporate resources in determining the industrial and geographical boundaries of the firm's activities. 5At the business strategy level, explorations of the relationships betweenresources, competitio n, and profitability include the analysis of competitiveimitation,b the appropriability of returns to innovations, 7 the role of imperfect information in creating profitability differences between competing

Tht' Rt'Souru-Bast'd Tht'on ufCompt'titi 't' Ad antagt'liSfirms, and the means by which the process of resource accumulation cansustain competitive advantage."Together, these contributions amount to what has been termed "theresource-based view of the firm." As yet, however, the implications of this"resource-based theory" for strategic management are unclear for tworeasons. First, the various contributions lack a single integrating framework. Second, little effort has been made to develop the practical implications of this theory. The purpose of this article is to make progress onboth these fronts by proposing a framework for a resource-based approachto strategy formu lation which integrates a number of the key themes arisingfrom this stream of literature. The organizing framework for the article is afive-stage procedure for strategy formulation: analyzing the firm's resourcebase; appraising the firm's capabilities: analyzing the profit-earningpotential of finn 's resources and capabilities; selecting a strategy; andextending and upgrading the firm's pool of resources and capabilities.Figure I outlines this framework.Figure 1. A Resource-Based Approach to Strategy Analysis:A Practical Framework4 Select a strategy whtch bestexploits the f1rm·s resourcesand capab1ht1es relat1ve toexternal opportunities.3 Appraise the rent-generatingpotent1al of resources andcapabilities in terms of:(a) their potential forsustainable competitiveadvantage, and(b) the appropriablhty oftheir returns.tt2 ldent1fy the firm's capabilities:What can the firm do more effectively Capabilitiesthan its rivals? Identify the resourcesinputs to each capability, and thecomplexity of each capability1 Identify and crass fy the f1rm'sresources Appra1se strengths andweaknesses relative to competitors.Identify opportunities for betteruttlizahon of resourcest5. Identify resource gapswhich need to be filledInvest in replenishing,augmenting and upgrad1ngthe firm's resource base

116CAuf ORNIA M \NACEME/1/T R vu::v.Spring 1991Resources and Capabilities as the Foundation for StrategyThe case for making the resources and capabilities of the firm the foundation for its Jong-tenn strategy rests upon two premi!les: first, internalresources and capabilities provide the basic direction for a firm's strategy,second, resources and capabilities are the primary source of profit forthe finn.Resources and Capabilities as a Source of Direction-The starting pointfor the formulation of strategy must be some statement of the firm's identityand purpose-conventionally this takes the form of a mission statementwhich answers the question: ''What is our business?" Typically the definition of the business is in terms of the served market of the firm: e.g.,"Who are our customers?" and "Which of their needs are we seeking toserve?" But in a world where customer preferences are volatile, the identityof customers is changing, and the technologies for serving customerrequirements are continually evolving, an externally focused orientationdoes not provide a secure foundation for formulating long-tem1 strategy.When the external environment is in a state of flux, the finn's own resourcesand capabilities may be a much more stable basis on which to define itsidentity. Hence, a definition of a business in terms of what it is capable ofdoing may offer a more durable basis for strategy than a definition basedupon the needs which the business seeks to satisfy.Theodore Levitt's solution to the problem of external change was thatcompanies should define their served markets broadly rather than narrowly:railroads should have perceived themselves to be in the transportation business, not the railroad business. But such broadening of the target market isof little value if the company cannot easily develop the capabilities requiredfor serving customer requirements across a wide front. Was it feasible forthe railroads to have developed successful trucking, airline, and car rentalbusinesses? Perhaps the resources and capabilities of the railroad companies were better suited to real estate development. or the building andmanaging of oil and gas pipelines. Evidence suggests that serving broadlydefined customer needs is a difficult task. The attempts by Merrill Lynch,American Express, Sears, Citicorp, and , most recently, Prudential-Bacheto "serve the full range of our customers' financial needs" created seriousmanagement problems. Allcgis Corporation's goal of "serving the needs ofthe traveller" through combining United Airlines, Hertz car rental, andWestin Hotels was a costly failure. By contrast, several companies whosestrategies have been based upon developing and exploiting clearly definedinternal capabilities have been adept at adjusting to and exploiting externalchange. Honda's focus upon the technical excellence of 4-cycle enginescarried it successfu lly from motorcycles to automobiles to a broad range ofgasoline-engine products. 3M Corporation's expertise in applying adhe5tive

Tht Rt.murct·IJtl.lt'd Tht'ory ofComptlt/11'1' lod ama11t117and coating technologies to new product development has pennilied profitable growth over an ever-widening product range.Resources as tbe Basis for Corporate Profitability-A finn's ability tocam a rate of profit in excess of its cost of capital depends upon two factors:the attractiveness of the induMry in which it is located, and its establishmentof competitive advantage over rivals. Industrial organization economicsemphasites industry attractiveness as the primary basis for superior profitability, the implication being that strategic management is concerned primarily with seeking favorable tndustry environments, locating attractivesegments and strategic groups within industries, and moderating competitive pressures by influencing tndustry structure and competitors' behavior.Yet empirical investigation has failed to support the link between industrystructure and profitability. Most studies show that differences in profitability within industries are much more important than differences betweenindustrieS. 10 The reasons arc not difficult to find: international competition,technological change, and divcrc;ification by firms across industry boundanes have meant that industries wh1ch were once cozy havens for makingeasy profits are now subject to v1gorous competition.The finding that competitive advantage rather than external environmentsis the pnmary source of inter-firm profit differentials between firms focusesattention upon the sources of competitive advantage. Although the competitive strategy literature has tended to emphasize issues of strategic positioning in terms of the choice between cost and differentiation advantage,and between broad and narrow market scope, fundamental to these choicesi the resource position of the finn. For example. the ability to establisha cost advantage requires po session of scale-efficient plants, superiorprocess technology, ownership of low-cost sources of raw materials, oraccess to low-wage labor. Similarly, differentiation advantage is conferredby brand reputation, proprietary technology, or an extensive sales andservice network.This may be summed up as follows: business strategy should be viewedless as a quest for monopoly rents (the returns to market power) and moreas a quest for Ricardian rents (the returns to the resources which confercompetitive advantage over and above the real costs of these resources).Once these resources depreciate, become obsolescent, or are replicated byother firms, so the rents they generate tend to disappear. 11We can go further. A clo r look at market power and the monopoly rentit offers, suggests that it too h it basis in the resources of firms . The fundamental prerequisite for market power is the presence of barriers to entry. Barriers to entry are based upon cale economies, patents, experienceadvantages, brand reputation, or some other resource which incumbentfirms possess but which entrants can acquire only slowly or at disproportionate expense. Other structural sources of market power are similarly

liSCALIFORNIA MANACE.\fENT R VI . WSpring 1991based upon finns' resources: monopolistic price-setting power dependsupon market share which is a consequence of cost efficiency, financialstrength, or some other resource. The resources which confer market powermay be owned individually by firms, others may be owned jointly. Anindustry standard (which raises costs of entry), or a cartel, is a resourcewhich is owned collectively by the industry memben." Figure 2 summarizes the relationships between resources and profitability.Taking Stock of the Firm's ResourcesThere is a key distinction between resources and capabilities. Resources areinputs into the production process-they are the basic units of analysis.The individual resources of the finn include items of capital equipment,skills of individual employees, patents, brand names, finance, and so on.Figure 2. Resources as the Basis for Profitability, ,Ill') Barriers to Entry., . Brands Retaliatory capabilityIndustryAttractiveness ., Monopolyi.'IRate of ProfitIn Excess of theCompetitive Level\/::: :::;;:;:::;::: ., FirmsizeVerticalBarga"ning Power- - - - - - - ' . F1nanc1al resources(costAdvantage. , Size of Plants Access to low-cost inputsCompetitiveAdvantage" ' - Marketing, distribution,and service capabilities

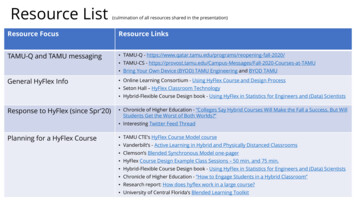

119But, on their own, few resources are productive. Productive activityrequires the cooperation and coordination of teams of resources. A capability is the capacity for a team of resources to perform some task or activity. While resources are the source of a firm's capabilities, capabilities arethe main l.ource of its competitive advantage.Identifying Resources-A major handicap in idcnttfying and appraising afirm's resources is that management information systems typically provideonly a fragmented and incomplete picture of the firm's resource base.Financial balance sheets arc notoriously inadequate because they disregardintangible resources and people-based skills-probably the most strategically important resources of the firm. Classification can provide a usefulstarting point. Six major categories of resource have been suggested: financial resources, physical resources, human resources, technologicalresources, reputation, and organizational resources .' The reluctance ofaccountants to extend the boundaries of corporate balance sheets beyondtangible assets partly reflects difficulties of valuation. The heterogeneityand imperfect transferabiltty of most intangible resources precludes the useof market prices. One approach to valuing intangible resources ill to takethe difference between the stock market value of the firm and the replacement value of its tangtble assets. 16 On a similar basts, valuation rattos provide some indication of the importance of firms· intangible resources. TableI shows that the highest valuation ratios are found among companies with .valuable patents and technology assets (notably drug companies) and brandrich consumer-product companies.The primary task of a resource-based approach to strategy formulation ismaximizing rents over ttme. For this purpose we need to investtgate therelationship between resources and organizational capabilities. However,there are also direct links between resources and profitability which raiseissues for the strategic management of resources: What opportunities exi.\1 for economizing on the use of resources? Theability to maximize productivity is particularly important in the case oftangible resources such as plant and machinery, finance, and people. Itmay involve using fewer resources to support the same level of bu iness,or using the existing resources to support a larger volume of busmess.The success of aggressive acquirors, such as ConAgra in the U.S. andHanson in Britain, is based upon expertise in rigorously pruning thefinancial, physical, and human assets needed to support the volume ofbusiness in acquired companies. What are the possibilitie. for using existmg assets more imensely and inmore profitable employment? A large proportion of corporate acquisitions are motivated by the belief that the resources of the acquired company can be put to more profitable use. The returns from transferringexisting assets into more productive employment can be substantial.

uoSpring1991The remarkable turnaround in the performance of the Wah DisneyCompany between 1985 and 1987 owed much to the vigorous exploitation of Disney's considerable and unique assets: accelerated development of Disney's vast landholdings (for residential development as wellas entertainment purposes); exploitation of Disney's huge film librarythrough cable TV, videos. and syndication; fuller utilization of Disney'sstudios through the formation of Touchstone Fi lm ; increased marketingto improve capacity utll11ation at Disney theme parks.Identifying and Appraising CapabilitiesThe capabilities of a firm arc what it can do as a result of teams ofresources working together. A firm 's capabilities can be identified andappraised using a standard functional classification of the firm's activities.Table 1. Twenty Companies among the U.S. Top 100 Companieswith the Highest Ratios of Stock Price to Book Value onMarch 16, 1990.Companylndu.tryValuation RatioCoca ColaBeverages877MicrosoftComputer software8.67MerckPharmaceuticals839American Home Products800Wal Mart Stores751Limited6.65Pharmaceuticals6.34Poltutoo control6.18Marnon Merrell Dow6.10McCaw Cellular Communications5.905.48Bristol Myers Squ1bbPharmaceuticalsToysRUsHealth care productsMCI CommunicationsTelecommunications4.80Eli LillyPharmaceut,cals4.70KelloggFood products4.58H.J HeinzFood products4.38PepsicoBeverages433Source: The 1990 Busmess Week Top 1000

1'1I ht Resource-Baft'tl Thtnr\' nf Compttitht' Atll'lmtag '121For example, Snow and Hrebiniak examined capabilities (i n their tenninology. "distinctive competencies") in relation to ten functional areas. 17 Formost finns, however, the most important capabilities are likely to be thosewhich arise from an integration of individual funct1onal capabilities. Forexample, McDonald 's possesses outstanding functional capabilities withinproduct development, market research, human resource management, finan cial control , and operations management. However, critical to McDonald 'ssuccess is the integration of these functional capabilities to createMcDonald 's remarkable consistency of products and services in thousandsof restaurants spread across most of the globe. Hamel and PrahaJad use thetenn "core competencies·· to describe these central, t rategic capabilities.They are "the collective learning in the organization. e11pecially how tocoordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technology."'" Examples of core competencies include: NEC's integration of computer and telecommunications technology Philips' optical-media expertise Casio's harmonization of know-how in miniaturization, microprocessordesign, material science, and ultrathin precision casting Canon's integration of optical, microelectronic, and precision-mechanicaltechnologies which forms the basis of its success in cameras , copiers,and facsimile machines Black and Decker's competence in the design and manufacture of smallelectric motor ;A key problem in appraising capabilities is maintaining objectivity.Howard Stevenson observed a wide variation in senior managers' perceptions of their organizations' distinctive competencies. 'q Organizationsfrequently fall victim to past glories, hopes for the future, and wishfulthinking. Among the failed industrial companies of both America andBritain are many which believed themselves world leaderc; with superiorproducts and customer loyalty. During the 1960s, the CEOs of both HarleyDavidson and BSA-Triumph scorned the idea that Honda threatened theirsupremacy in the market for · serious motorcycles."ll' The failure of the U.S.steel companies

A Resource-Based Approach to Strategy Analysis: A Practical Framework 4 Select a strategy whtch best exploits the f1rm·s resources and capab1ht1es relat1ve to external opportunities. 3 Appraise the rent-generating potent1al of resources and capabilities in terms of: (a) their potential fo