Transcription

AssociateProfessors Feel theSqueezeFindings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveySponsored by:

IF WE’RE NOT ON YOURRADAR,THERE’S SOMETHING SERIOUSLYWRONG WITH YOUR RADAR.Last year, TIAA-CREF posted impressiveresults. But that’s nothing new. Long-termperformance is what we’re all about. Seewhat our award-winning funds can do for yourfinancial health. The sooner you act, the better.Learn more in one click at TIAA.orgor call 855 200-7243.contentsStuck in the MiddleAssociate Professors See Their Earning Power DropCompared with Their Colleagues Above and BelowPay Has Grown Slowly for Manyin the MiddleThe Lipper Award is given to the group with the lowest average decile ranking of three years’Consistent Return for eligible funds over the three-year period ended 11/30/12 and 11/30/13,respectively. TIAA-CREF was ranked against 36 fund companies in 2012 and 48 fund companiesin 2013 with at least five equity, five bond, or three mixed-asset portfolios. TIAA-CREF Individual& Institutional Services, LLC, and Teachers Personal Investors Services, Inc., members FINRA,distribute securities products. C17745A 2014 Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association ofAmerica – College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF), 730 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017.1BEST OVERALL LARGE FUND COMPANY1The Lipper Awards are based on a reviewof 36 companies’ 2012 and 48 companies’2013 risk-adjusted performance.Consider investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefullybefore investing. Go to tiaa-cref.org for product and fund prospectusesthat contain this and other information. Read carefully before investing.TIAA-CREF funds are subject to market and other risk factors. Pastperformance does not guarantee future results.Faculty Salaries at Private andPublic Colleges, 2013-14Women Face More Disparity in Pay andRepresentation at Academe’s Top Levels[5][10][11][12]

Findings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveyStuck in the MiddleAssociate Professors SeeTheir Earning Power DropCompared with TheirColleagues Above and BelowAssociate professors, in theory, should behitting a stride in their academic careers.In the middle ranks of faculty, they havetypically earned tenure and started to take onbroader responsibilities in their departments,juggling more service and governanceroles with their teaching and research.But the earning power of these professorsis diminishing compared with theirpeers in ranks above and below them.About the AAUP Salary SurveyEach spring, the AAUP publishes its report on faculty compensation and the economics of higher education.AAUP members receive a print copy of the report (with complete data listings) as part of their membership.Data from the survey are also available for purchase in several formats, including institutional peercomparison reports, complete datasets, and pre-publication report tables. For more information aboutordering data from the AAUP, contact aaupfcs@aaup.org.For a complete view into AAUP Salary Survey data, including a look at how facultysalaries have changed over time, go to Chronicle.com/2014salarysurveyWhile pay for associate professors has grownby 5.6 percent since 2000, after adjusting forinflation, salaries for assistant professorshave increased by 9 percent, according to aChronicle analysis of data provided by theAmerican Association of University Professors.The gap is widening even more betweenassociate professors and full professors,whose pay has increased by 11.7 percent.However, the association cautions thatthe recession’s effect on faculty salariesisn’t over yet. Professors who work at thesame institutions as the year before sawan average pay raise of 3.4 percent, whichis still below pre-recessionary levels.The report, titled “Losing Focus,” alsopoints out lingering inequities: Pay atprivate colleges, it says, continues to behigher than at public institutions. And thereport questions institutions’ focus ontheir core academic mission, given theirdecisions to grow administrative ranksand increase spending on athletics.The average salary for full-time facultymembers, the association found, rose2.2 percent in 2013-14 from the yearbefore. For the first time in five years, theincrease in salaries outpaced inflation.[5]

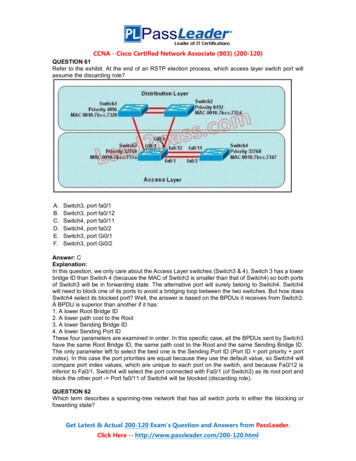

Findings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveyFaculty PayDespite that kind of environment, in which littlemoney is typically available or set aside for increasingfaculty pay, salaries for assistant professors are risingat a faster rate than those of associate professors—mainly because institutions put together competitivepay packages every year to lure new junior facultymembers to campus. That leaves associate professors,and even some full professors, to commiserate aboutsalary compression as the gap narrows betweentheir pay and that of their newly hired colleagues.“Deans and other administrators face a number ofconstraints as they make hard choices about howto allocate limited funds for salaries. They have toBeginning assistant professors can certainly make more thanestablished associate professors in my department.The average salary for an assistant professor acrossall types of institutions is 69,848 in 2013-14,compared with 81,980 for an associate professor,according to AAUP data—a gap of about 12,000.“I see this all the time as I try to hire people on theopen market,” says Antony H. Harrison, a professorof English and head of the department at NorthCarolina State University. “Beginning assistantprofessors can certainly make more than establishedassociate professors in my department.”“It’s a huge problem,” he continues. “For us, therejust aren’t that many tools in the tool box thatyou can work with to make a difference.”Meanwhile, the gap between the average salaries ofassociate professors and full professors is just over[6] 37,000. Salaries for full professors generally rise at afaster rate than those of other ranks, in part becauseraises and merit pay are typically awarded as a percentageof their already larger base salary. Over time the pay gapbetween them and their colleagues in other ranks willcontinue to grow when measured in absolute dollars.”manage faculty morale as tight budgets limit thepossibility of raises, and they must weigh how torecruit new faculty and find money to retain professorswho are offered bigger paychecks elsewhere.“The only way to get a significant raise is to movesomewhere else,” says Lynn E. Fisher, an associateprofessor of anthropology at the University ofIllinois at Springfield. “And of course that’s a lossof experience and training to the university.”Ms. Fisher is one associate professor whose salary hascrept up only incrementally in recent years. She waspromoted to her current rank at the start of the 20067 academic year. At the time, the move increased herbase salary by 2,500. Since then pay raises for theuniversity’s faculty have been sporadic; they werenonexistent in the years following the recession.Last year, however, employees across the boardin the University of Illinois system receivedmerit raises that averaged 2.75 percent.For associate professors like Ms. Fisher, the nextsubstantive bump in salary would most likely come witha promotion to full professor. At Springfield, advancementto that rank means a 5,000 boost in pay. To apply forthe promotion, associate professors must be at that rankfor at least seven years and “be able to document a clear“The only way to get asignificant raise is tomove somewhere else.”record of excellence in teaching, research, and service,”among other things, according to university guidelines.The path to full professor, and the subsequent financialpayoff, is often fraught with barriers, particularlyfor women and minority faculty members. Researchshows that both groups are often disproportionatelysaddled with service activities, such as mentoringundergraduates and sitting on departmentaland university-wide committees, and familyresponsibilities that make it tough for them to takeon the kind of work that counts toward promotion.“In many departments and institutions, the cultureand support for professors to come up to full is justnot there,” says Kiernan Mathews, director of theCollaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Educationat Harvard University, which studies the attitudes facultymembers have about their jobs. “What we’ve learnedis that the experience of the newly tenured associateprofessors is a heavier course load and more servicework, perhaps even serving as department chair. They’reasked to do all these other additional things withoutany support to continue their research productivity.”How much earning power associate professors havevaries by the type of institution at which they areemployed. According to the AAUP data, they fare theworst compared with their peers at master’s institutions,where their pay, after adjusting for inflation, fellby 0.3 percent since 2000-1. Associate professorsfared the best at doctoral institutions, where theirpay rose 7.1 percent when adjusted for inflation.The severity of gaps also varies by campus. At Springfield,where Ms. Fisher works, the average associate professor’spay fell 11 percent between 2000-1 and 2013-14, whenadjusted for inflation. In comparison, full professors sawa 21-percent jump in pay. The average pay for associateprofessors at the University of Chicago rose from 107,500in 2000 to 118,900 in 2013-14—an increase of 11 percent.But full professors’ average pay rose by 25 percent duringthat time, from 168,800 to 210,700. At VanderbiltUniversity, the average pay for associate professorswent up 19 percent to 107,500, but average pay for fullprofessors outpaced that with a 25-percent jump.Associate professors’ salaries may be slow-growingpartly because of the kinds of faculty members who tendto be part of that rank. Some, for example, never seekpromotion. Such longtime associates may have beenplanning to retire before the recession hit, Mr. Mathewssays. However, it’s possible that they’ve now put off thoseplans and are locked into incremental raises, if any.[7]

Findings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveySalary by Faculty Rank, 2000-1 to 2013-14 119K 107KIn 2013-14, the gap hasgrown to 37KThe gap between full and associateprofessors was 29K in 2000-1 82K 78K 70K 64K2000-12013-14Full ProfessorAssociate ProfessorNadine Bean, who has been an associate professor ofsocial work at West Chester University of Pennsylvaniafor nine years, has decided not to apply for a promotion.That means she is also passing up the pay bump thatcomes with a move to full professor. She says shehas come to realize that meeting the requirementsfor promotion would be a stretch for her.“I’m supposed to do 50 percent teaching, 35 percentresearch, and 15 percent service, and my research andservice is reversed,” says Ms. Bean, who worked as asocial worker for 25 years before starting a career inacademe. “I’m just very active in my profession and indirect service, actively engaging students in the workthat I do. To apply for full, I would have to dramaticallychange my priorities, and I’m just not willing to do that.”[8]Assistant ProfessorMs. Bean’s decision means she’ll forego a 10- to12-percent jump in pay at an institution where theaverage pay for professors at her rank is 85,500.Those who have remained at their ranks have beenreceiving raises of 1 to 2 percent in recent yearsas stipulated by the faculty’s union contract.At some institutions, associate professors and othersdon’t have to rely solely on raises or promotions toearn extra money. At Central Michigan University, forexample, professors of all ranks can earn more pay forteaching courses online or during the summer (althoughthe money wouldn’t be added to their base salary), saysJoshua Smith, an associate professor of philosophy andreligion and president of the university’s faculty union.A promotion to associate professor at Central Michigancomes with a base salary increase of 6,250, accordingto Mr. Smith, and a promotion to full professor comeswith an increase of 7,250. Full professors, however,also have a built-in opportunity to increase theirearning power at a greater rate than professorsof other ranks. Every four years they can earn thesame pay raise they did when they were promotedto full professor if they meet the same criteria.“There’s a strong motivation to get promotedand stay active,” Mr. Smith says.That same kind of incentive exists at the University ofCalifornia at Santa Barbara, where AAUP data show that,when adjusted for inflation, average pay for associateprofessors has risen just 1 percent since 2000-1. Yetthe average pay for full professors at the institutiongrew only 5 percent, from 138,300 to 145,200.Within the University of California system,professors of any rank have a process they caninvoke if they believe they are underpaid and wanta review of their record and achievements.“Sometimes you can find assistant and associateprofessors with higher salaries than full professors,”says Mr. Marshall. “We’re aware of the pressure ofmarket forces when you’re dealing with recruitmentand retention. All universities are dealing with this.“Still, we do try to keep a sense of the wholepicture,” he says, “and balance that withwhat’s happening with individuals.”Jonah Newman contributed to this article.“There’s a strong motivationto get promoted andstay active.”“People who are doing good work have a path tomove forward and advance throughout their entirecareer,” says David Marshall, dean of the divisionof humanities and fine arts at Santa Barbara.Faculty at all ranks are also promoted in “steps,”which means that it’s possible to get a raise everyfew years within the same rank before moving on tothe next one. A faculty member who has exceededexpectations for a particular step could skip itand move on to the next, Mr. Marshall says.The pay hierarchy can also be changed, sometimessignificantly, when the university counters an offerfor a job a faculty member receives elsewhere orwhen the university makes an aggressive play toland a hotly sought-after assistant professor.[9]

Findings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveyPay Has Grown Slowly forMany in the MiddleFaculty Salaries at Privateand Public Colleges, 2013-14Across all types of institutions, associate professors—usually those with tenure but lacking in published papers—havelost ground to their academic peers in terms of pay. The average salary for associate professors at doctoral universities hasincreased at half the pace of full professors’ salaries. Meanwhile, professors of all ranks at two-year colleges have faredthe worst. Struggling to keep up with inflation even in the best of times, and still not fully rebounded from pre-recessionhighs, salaries at associate institutions are actually lower today than they were in 2000, when adjusted for inflation.Averaged across all ranks, faculty at public doctoral universities now earn less than 75 percent as much as their privatenon-religious peers. At the master’s level, pay for public-college faculty is about 86 percent of pay at private institutions.At baccalaureate colleges, pay at public institutions is 82 percent of that at private institutions.Average Salaries of Full-Time Faculty Members at Private vs. Public InstitutionsAverage Salaries of Full-Time Faculty Members by Institution TypeFull ProfessorAssociate ProfessorAssistant ProfessorDoctoral 140K 120K 120K 100K 100K 80K 80K 60K 60K 40K 40K2013-14Baccalaureate 120K 120K 100K 100K 80K 80K 60K 60K 40K 40K2000-1Note: Figures adjusted to 2013 constant dollars.2013-14Professor 173,890 126,981AssociateAssistantInstructorLecturerNo RankAll 56775,43250,03255,62361,156 91,918Professor 107,082 90,517AssociateAssistantInstructorLecturerNo RankAll Combined80,86868,29054,67259,75169,587 81,91972,86962,63646,31049,72754,896 70,683 106,641 87,26279,07364,26250,39564,79564,146 82,03170,84959,87349,29751,58255,143 67,328Master’s2013-14associate 140KPublicDoctoral2000-1 140KPrivate*InstructorMaster’s 2013-14Source: American Association of University Professors;Bureau of Labor Statistics.AssociateAssistantInstructorLecturerNo RankAll Combined* “Private” excludes religious-affiliated institutions.Source: American Association ofUniversity Professors.[11]

Findings from the 2014 AAUP Salary SurveyWomen Face More Disparity in Pay andRepresentation at Academe’s Top LevelsWomen remain underrepresented in the academic workplace, particularly at the highest levels, in 2013-14. Among fullprofessors at doctoral universities, there’s one woman for every three men, and women earn, on average, 91 cents perdollar paid to their male counterparts. Meanwhile, women account for more than half of all full-time faculty members attwo-year-colleges. The pay disparity is lowest there, but so are the salaries.Percentage of Full-time Faculty andDoctoralmaster’sPercentage ofAll Full-Time Faculty8.4% 127,85826%9.7%18.4% 86,66715.8% 93,06210.4% 72,82615.2% 74,79911.6%3.3% 51,3792.2%4.5% 53,722 47,6722.6% 48,7605% 55,3094% 62,669FemaleMaleNote: Faculty without academic rank not included.15.9%4.5% 49,5493.4% 53,148FemaleMale11.5% 63,115 59,28015% 60,505 53,31712.5% 53,916Instructor3.8% 48,4152.3%9.2% 48,924 46,7917.1% 47,276LecturerLecturerLecturerLecturer 61,364AssistantInstructorInstructorInstructor 77,64313.7% 72,89713.9% 65,11014.5% 70,83716.3% 62,406 77,245AssociateAssistant12.4%13.1% 95,55113.7% 76,21414.4% 82,38118.6%AssociateAssistantAssistant 91,571 95,83813.1%Average SalaryProfessor10.2% 90,312Associate10.9%Percentage ofAll Full-Time FacultyAverage SalaryProfessor 141,883AssociateassociatePercentage ofAll Full-Time FacultyAverage e ofAll Full-Time FacultyAverage SalaryAverage Salary of Males vs. Females1.8% 53,2401.5% 56,878FemaleMale1.9% 47,3791.2% 47,639FemaleMaleSource: American Association of University Professors.[13]

WE HELPWOMENAVOID INVESTING LIKE A MAN.At TIAA-CREF, we give women one-on-one financialadvice in person and online, at no extra charge.1There’s also advice and insight at our onlinecommunity, Woman2Woman. It works too. Ina study, 68% 2 of participants we advised tookaction to improve their retirement readiness.Learn how we do it injust 2 clicks at TIAA.orgAbout the DataSalary data are collected annually by the American Association of University Professors. Participation inthe AAUP survey is optional; 1,157 institutions submitted data for the 2013-14 academic year. Salaries arerounded to the nearest hundred dollars. Where faculty contracts are 11 or 12 months long, salaries areadjusted for a nine-month work year.Restrictions apply. Must be enrolled in a TIAA-CREF retirement plan to be eligible. 2 Source:TIAA-CREF Outcomes Chart Report 2011-2012. 3 The Lipper Award is given to the group withthe lowest average decile ranking of three years’ Consistent Return for eligible funds over thethree-year period ended 11/30/12 and 11/30/13, respectively. TIAA-CREF was ranked against36 fund companies in 2012 and 48 fund companies in 2013 with at least five equity, five bond,or three mixed-asset portfolios. Past performance does not guarantee future results. For currentperformance and rankings, visit the Research and Performance section on tiaa-cref.org.TIAA-CREF Individual & Institutional Services, LLC, and Teachers Personal Investors Services Inc.C17459 2014 Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America – College RetirementEquities Fund (TIAA-CREF), 730 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017.1For a complete view into AAUP Salary Survey data, including a look at how facultysalaries have changed over time, go to Chronicle.com/2014salarysurveyBEST OVERALL LARGE FUND COMPANY 3The Lipper Awards are based on a reviewof 36 companies’ 2012 and 48 companies’2013 risk-adjusted performance.Consider investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefullybefore investing. Go to tiaa-cref.org for product and fund prospectusesthat contain th

About the AAUP Salary Survey Each spring, the AAUP publishes its report on faculty compensation and the economics of higher education. AAUP members receive a print copy of the report (with complete data listings) as part of their membership. Data from the survey are also available for