Transcription

Acquisition Cost and Nutritional Data on Great Basin ResourcesAuthor(s): STEVEN R. SIMMSSource: Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1985), pp. 117-126Published by: Malki Museum, Inc.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825220Accessed: 30-11-2015 18:34 UTCYour use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at s.jspJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of contentin a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.Malki Museum, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of California and GreatBasin Anthropology.http://www.jstor.orgThis content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ACQUISITIONCOST AND NUTRITIONALDATAMinor, Rick, and Ruth L. Greenspan1985 Archaeological Testing in the Southeast Areaof the Headquarters Site, Malheur NationalWildlife Refuge, Harney County, Oregon.Eugene: Heritage Research Associates Report No. 36.Moyle, Peter B.1976 Inland Fishes of California. Berkeley: University of California Press.Pettigrew, Richard M.1985 ArchaeologicalInvestigations on the EastShore of Lake Abert, Lake County, Oregon.University of Oregon Anthropological PapersNo.Kathryn Anne, Rick Minor,Toepel,Snyder, John Otterbein1908 Relationships of the Fish Fauna of theLakesof Southeastern Oregon. United States Bureau of Fisheries Bulletin 27: 69-102.1917 The Fishes of the Lahontan System ofNevada and Northeastern California. UnitedStates Bureau of Fisheries Bulletin 35:31-86.1984 Archaeological Testing in Diamond Valley,Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, HarneyCounty, Oregon. Eugene: Heritage ResearchAssociates Report No. 30.Toepel, Kathryn Anne, Rick Minor, and William F.Willingham1980 Human Adaptation in the Fort Rock Basin:A Class II Cultural Resources Inventory ofin Christmas Lake Valley,BLM LandsSouth-central Oregon. Report on file at theBureau of Land Management, Lakeview,Oregon.Acquisition Cost andNutritional Data onGreat Basin ResourcesSTEVEN R. SIMMSAs part of an earlier study (Simms 1984),data on the costs and benefits of obtainingnativeSpier, Leslie1930 Klamath Ethnography. University of California Publications in American Archaeologyand Ethnology 30.Stewart, Omer C.1941 Culture Element Distributions, XIV: Northern Paiute. University of California Anthropological Records 2(3).Thomas, David Hurst1981 How to Classify the Projectile Points fromMonitor Valley, Nevada. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 3: 7-43.Toepel, Kathryn Anne, and Stephen Dow Beckham1981 Survey and Testing of Cultural Resourcesalong the Proposed Bonneville Power Administration's Buckley-Summer Lake Transmission Line Corridor, Central Oregon. Eastern Washington University Reports in Archaeology and History 100-5.and Ruth L.Greenspan32.Phillips, Kenneth N., and A. S. Van Denburgh1971 Hydrology and Geochemistry of Abert,Lakes, and OtherSummer, and GooseClosed-basin Lakes in South-central Oregon.United States Geological Survey ProfessionalPaper 502-B.117resourcesfoodin the GreatBasin werefor usein foraging modelsdevelgeneratedoped from evolutionaryecology. Portions ofthese data are presented here for the benefitofin the acquisitionfoods.1interestedresearcherscosts and nutritionof wilddata represent handling costs only;Theseonce a resourcethat is, the cost of acquisitionaretohas been encountered.Theyapplicablea variety of questions,some beyondthe goalsofthe studythey werefor whichcollected,involving the addition and deletion of resourcesto humandatanutritionalinterestedand mayrequiringenergy.diets.shouldThebeaccompanyingto thoseusefulin the food value of wild plants,also prove useful in foraging modelsthe analysis of variables other thanOnthe otherhand,Steven R.of SociologySimms, Dept.Weber State College, Ogden, UT 84408.This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditionsdataonsearchand Anthropology,

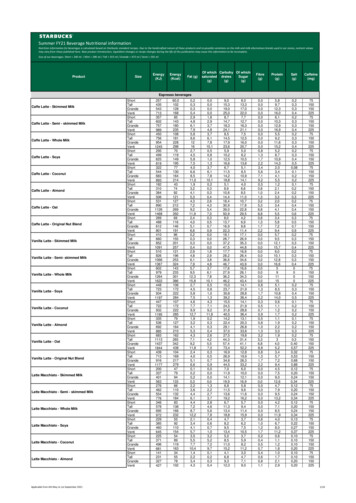

JOURNALOF CALIFORNIAAND GREAT BASINANTHROPOLOGY118costs reported in Simms (1984) tend to bemoreis beyond the scope of thispaper. ssionsbefoundofinissuesSimms(1984).cost/benefit data presented here arereturn rates measexpressed as post-encounterured in units of energy acquired per unit ofcosts are termed "hantime. Post-encounterThetime"dlingresourceaboutcan be usedandato constructtorankingdietary breadth.for makingorder in whichtoolinvestigatequestionsResourceranking is ainitial predictionsabout theresources will be added to orfrom a changingdeleteddiet (e.g., MacArthurand Pianka 1966; Charnov and Orians 1973;O'Connell and Hawkes 1984; Simms 1984:30-35).searchresourcesome knowledgeHowever, withoutiswhichtime,primarily a functionofofit is not possible to makeabundance,aboutthe proportionalcontribupredictionstion of a resource to the total diet. Neverthethat manysubsistenceless, givenchangesinobservablethe archaeologicalrecord are ofthe diet-breadthtype where a resource is firstbecomingutilizedhandlingtimeologyanceor being deleted,be informative.candataonArchaeis replete with cases where the appearor disappearancein theof resourcesenvironmentandbutoccurred,past relativeelusive.Thedietareknownto havewhereabouttheknowledgeof resources remainsquantitiesis an impordiet-breadth modeltant starting pointbecauseit is well matchedto a level of data typically found in thearchaeologicalrecord.Twoexamplesthatshow the kinds of applications possible andillustrateevidentsomeoftheby this approachmaderelationshipsare included here.METHODSreturn rates and repost-encountersource rankings discussedin this paper werederived from direct field d their servations(animals). Methodsare described below.measurementofPlantsfor plants were obdataHandling-timecontainedexperimentsthrough collectingducted between 1980 and 1982. Only ileconductedthe collectinglearningreliablethat produceddata werethis excludesexthe authorwasFiguretechniques.1 identify the field experimentand TableTable 1LOCATIONSLIST OF PLANT-GATHERINGSHOWN IN FIGURE 1ReferenceNumber onFig. 1ResourcesLocation1Gund2Pine ValleyCollectedElymus cinereus, Sitanionstrierahystrix, DistichlisRanchcinereus, Sitanionstrie tahystrix, DistichlisElymus3PineValley4Ruby Mountains5Lepidium perfoliatumPoa bulbosaToanoRangenear Wend overPinus monophylla67CrystalhymenoidesOryzopsisPinus monophylla891PeakSkullValleyBaker Hot SpringsLewisiarediviva10near Grant svilleoccidentalis,AllenrolfeaScirpusA triplex confertifolia,11near GrantsvilieMuhA triplex nuttalli12near Grantsvilie13GreatSalt Lakelen ber gi? asp erifolia,jubatumScirpus, HordeumTypha latifoliaScirpus microcarpusQuer cus gam belli14Emigration15Great16Sevier RiverScirpusCanyonSalt LakeTypha latifolia17Sevier RiverPhalaris18Brine Creek19Abes Creek,Fishlake MountainshymenoidesOryzopsisPoa eValleyDistichlis22SanpeteValleyElymus23Ferron CreekMuhlenbergiaEchinocholoa24near HuntingtonHelianthusThis content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditionsstrictasalinasasp erifolia,cru sgalliannuus

ACQUISITIONCOST AND NUTRITIONALDATA? ?Batti* Mt?v; 'A?\\ wtndov?r Jl*? 3I-W njcfifc W* *7 1 ?I*9?I?t pTT? ? ?"fWEftSI "0lSCALEJi50'YI?SeItUk? City?6# TooftU'J. Vo Tu,eka119/t'y ?/& "60 kmMllford Fig. 1. Map showing locations of plant collecting experiments (see Tablelocations.andTablenoteson2 presents nutritional data,3 providesreturn-rate data edstrengthsandabouttheresources,in the data, andrelevant to specific asweaknessesissuesarchaeologicalpects of the data are offered in Simms (1984:Appendix).Few tools were used to collect the plantresources.Twoeachbaskets,open-facedcm. in diameterand 10 to 15 cm.about40deep,servedas receptacles.Onewasbowled,similar in design to ethnographicGreat Basinbaskets, and shallow enough to be effectiveinwinnowingsmall seeds. Ameasuring50wasflat winnowingtrayslightly dished metate,also used. Aby 25cm.,anda one-handedmano(e.g.,1 for key to reference numbers).were used when grinding was necessaryin the case of pine-nut hulling).The returnrates shown inTable 3 reflectthe costsin time of pursuitand processing.Pursuit time is that spent gathering theresourceatimeProcessingreceptacle.reflects the winnowingand parching of seedsto preparethem for storage. Seeds were notintoground intomeal. While thiswould add to theprocessing time, itwas found that formostseeds in theGreat Basin, grindingrepresentsasmall fractionof total processing time (Simms1984: 85). This would not hold true forlarger, harder seeds such as those of mesquite.Rootprocessing was limited to cleaning andremoval of the epidermis. The density ofplants withina stand can affect return rates toThis content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OF CALIFORNIAAND GREAT BASINANTHROPOLOGYJOURNALTable lfeaA triplex confertifoliaA triplex nut tall iCarexDescurainiaPercentProteinCal./kg.pinnastrie tataOF PLANT 17.4Echinocholoa3,5109.580.40.015.34.9ElymusEly Phalaris irpus acutus(roots chewed into quids)asp erifolia 0.304.534.5Typha of plant density wereon counts within sample areas,madebut these data are not reported here.somedegree.basedEstimatesto comparetheAlthoughexperimentsefficiency of various seed beaters against handcollectionof seeds were not routinely conducted, a stick seed beater (35 cm. long by 2cm. in diameter)a wovenand, occasionally,werebeaterused assesofresources(e.g., nuts vs. seeds vs. roots).Nutritionaldata were provided by FordChemical Labs in Salt Lake City, Utah. Alllessfor analysis weresubmittedspecimensthan three weeks old. Roots were kept cold inthe field, then frozen. In addition to calories,the sampleswere measuredfor protein, fats,The valuesand moisture.that exhibitedstructural difplantsferences. Commentsabout seed beater effecash,carbohydrates,for ash are largely a product of the parchingprocess. Seeds with chaff that was difficult totivenessremoveselectedbeatershigherbeater.3in Tablereferto whetherat all, and do notworkedreturn rates can be obtainedToimply thatby using acompare all of the variabilityversusof seed beaterseffectivenesswouldtechniquesmentsthan were(Simmsuresin theotherrequire many more experidonein the original study1984). Thereturn-ratethewasgoal in acquiring theto producedatato retendedlarger ash comtochaff that continuedto havefrom burnedato the seeds after parching.Animalsdata for animals were generHandling-costatedanimalof ediblethrough s) and estimates of the ranges of pursuitand processingtimes. TheThis content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditionsweightsused here

ACQUISITIONCOST AND NUTRITIONALDATA121Table 3PLANTRESOURCE RANKING:PURSUITAND PROCESSINGTIME AND RETURN RATEPursuitResource(hrs./kg.)0.12-0.307Typha iOak (acorns)Descurainiapinna ta1.0-1.10.8 2.0(seeds)TansymustardPinus monophylla(cones)Pinyon Pine 408 Pure pollen;can be madeinto cakes(Wheat1967:11).Lowertannin content than Californiaspecies; leachingif not a staple.unnecessaryseed beater effective; low processingWoventimerelative to most seeds.Brown cone procurementand picking nuts off the groundare measured;available over many weeks with successiveharvest strategies; ifmats are placed under tree asSteward (1933:241) reportedand Lanner (1981:102) hasredivivaLewisiaBitte rroot (roots)Ely mus1.4salinas0.91.2*1.61,2002.3 veralPoa sp. 3.0-5.71.1-5.0418-491Seed beater ineffective;at most 301-392Amenable6.5-12.51.4-2.9162-294Seed beater effectivenesson timing of harvest.2.5-11.18.7-11.1138-273Best whenannuusSeed beater fairly effective; native species requiresmore processingthan more common,introducedspecies, L. ratchgrassHordeumjubatumFoxtail Barley (seeds)10.62.2sp.Sedge (seeds)Typha AllenrolfeaPickleweed(seeds)SaltgrassSitanion hystrixSquirreltail Grass (seeds)using seed beater19.211.891tointo mid-late winter becauseLarge seeds; availableof tenacious attachments;seed beater effective.Low return rate during early-season(July) harvest;harvest of largehigh rate during late-season (October)seed species on dry ground; seed beater effective.1.7-4.9hymenoidesOryzopsisIndian Rice Grass (seeds)ScirpusBulrushExtremelyhigh density caused by stand growing nextagricultural field; high end of range in return rates,Similar to A. confertifolia,but small bracts requireless processing.1.0-2.1(seeds)Great BasinWild Rye lliBarnyard Grass (seeds)Lepidiumfre montiiCarex921-1,238(seeds)A triplex 0*SalinaWild Rye (seeds)A triplex nut talliNuttall Shadscale1.3done, return can rise to over 4,000 Cals./hr.; predatorcan alter return rates; nuts rich incompetitionin corn.tryptophan, an amino acid deficientUsed digging stick; skins come off best and areeasiest to find in late spring to early summer;return rates lower in other seasons.harvestspossibleat some stands.several weeksof availabilityto mass processing;cutting spikes andthreshing, seed beater ineffective except forbriefperiod duringharvestto mass processing;seed beateronly during peak harvest period.Higherpickedvariable;in masseseffectivedependentand processedreturn rates likely with betterby threshing.timing of harvest.High return rate with minimal processing(cleaning only);low return rate when starch removed by pounding;collected in large masses;low starch content in winter/to winter harvesting.spring; not amenableCollectedin large masses;cleaning and skin removalonly; return rate based on chewing roots into quids,inedible fraction not counted.toamenableLong availability(June-September);mass processing.Very small seeds; seed beater not effective; long(late Augustavailabilityearly November).Similar toDistichlis,but shorter span of availability.This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

122JOURNALOF CALIFORNIAAND GREATBASINANTHROPOLOGYTable 4ANIMAL RESOURCE RANKING: PURSUIT ANDPROCESSING TIME AND RETURN RATETotalResourceDeerPursuit(Cals./ind.)and relDucksfor large game are smaller than weights foundwhoin Whiteseemed to have exam(1953),ofratherinedEstimateslarge specimens.time were determinedpursuit and processingwith modernhuntersthrough conversationshavewhoand withforagedethnographersandwith hunter-gatherers(K. Hill, H. Kaplan,J. F. O'Connell,communicationspersonal1980-1984). As with the plants, the goal inand betweenwasclasseslarge vs. small game).data are bestTheseof estimatedrangedifferent huntingto makeordinalresourcesbetweengeneralspecificof resources(e.g.,as providing acosts forpost-encounterseensituationsthat involve widetimes. In the cases ofpursuitorpursuitbighorndeer, for example,sheepwas encountered.onceIf atheanimalbeganly varyingshortly after encounter, the pursuit time may have been only aor two (henceminutethe value of 0.02successfulkill was madehours/individualTable 4). Onhavetrackedfor deerpursuitshowninthe other hand, pursuit maytimeif an animal wasafter an unsuccessfulinitial encounterlastedfor some(Cals./hr.)30,888464637309140630dataReturn Rate0.0006-0.03Gophersthesedevelopinglevel l13-lined 900JackrabbitCottontail(hrs./ind.)(a maximumpursuit of one hour was used inthe case of large game). The time required foris not counted astracking prior to encounterpursuit, but falls into the category of searchtime. As with the plants, search time is highlyto questionsand 75-15,4000.0401.50the relative contributionthe diet. Presentation1,975-3,5932,709of resourcesof search-costdatatoandare beyondthe scope of this paper.data show an imporhandling-timeofthe componentstant relationship betweenexamplesThesepursuitlarge ranges in estimateda variationinhowtimes rsuitchange in the return rate. Table 4 shows thatcost.Thetake large differences in pursuit time,theranges shown here, to change thebeyondresource ranking. For example, even doublingto two hourstime for deer,the pursuitit wouldinstead of one, onlylowers the return rate fordeer from 17,971 Cals./hr. (Table 4) to12,580 Cals./hr. Similarly, if the pursuit timefor duck is doubled from the 0.156 hr./kg.used4 to 0.3 hr./kg.,in Tablethe return rateonly falls from 1,508 Cals./hr. (Table 4) to1,231 Cals./hr.In contrastto pursuittime, processingto the body size of the animal.Given the wide range in body sizes among therather thanit is processinghuntedanimals,inlarge variancespursuit time that producesto theis relevantthe return rates. Thistime is relativecriticism that hunting return ratespotentialsituations formust vary too much betweento be useful. Thethese datarelationshipcosts suggestsbetween pursuit and processingthat relativecessingbodytime maysize andbemoreThis content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:34:59 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditionsconsequentrevealingprothan

ACQUISITIONtime for ascertainingpost-encounterpursuitreturn rates. Thisis an example of only oneevident by conceptualizingrelationship madein terms of a diet-breadththe problemmodelthat requires pursuit and processing (whichare measuresof efficiency)from each otherseparatelyis a measure(whichto be consideredandfrom searchof resourceabundance).and searchOfcourse,processing,pursuit,are interactive and higher order foragingreveal relationshipsmodelsamong

A Class II Cultural Resources Inventory of BLM Lands in Christmas Lake Valley, South-central Oregon. Report on file at the Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview, Oregon. Acquisition Cost and Nutritional Data on Great Basin Resources STEVEN R. SIMMS As part of an earlier study (Simms