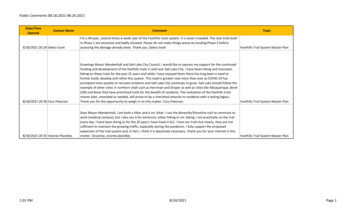

Transcription

TRAIL OF CTHULHUDOUBLE FEATURE“Furtiveness and secretiveness seemed universal in this hushed cityof alienage and death, and I could not escape the sensation of beingwatched ”-- H.P. Lovecraft, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth”century’s horror fiction, he was unwillingto completely abandon them in his ownwork. His earlier fiction happily trades insuch standard tropes, and even his laterhyper-scientific horrors recapitulate andreshape the Gothic horror archetypesrather than rejecting them entirely.This brief examination of Lovecraft’streatment of these standards may inspireTrail of Cthulhu Keepers to likewiseproject the classic figures through aCthulhoid lens.The VampireOn the surface, the two great streamsof horror that flowed out of the 1930swould seem to have little in common.H.P. Lovecraft’s “cosmic materialism”grew in intricate patterns of words,building sublime dread from the hintsand edges revealed by modern scienceand technology. The “monster rally”horror films of Carl Laemmle Jr’sUniversal Studios (and even moresoVal Lewton’s horror films for RKO),by contrast, kept the dialogue to aminimum and let light, shadow, andsound breathe life into the very samesupernatural horror clichés thatLovecraft had dismissed as defunctrelics of the previous century.Lovecraft certainly dismissed theUniversal horrors. In a 1933 letter, hewrote: “Last year an alleged Frankensteinon the screen would have made medrowse had not a posthumous sympathyfor poor Mrs. Shelley made me see redinstead. Ugh! And the screen Dracula in1931 – I saw the beginning of that inMiami, Fla. – but couldn’t bear to watchit drag to its full term of dreariness.”Hollywood repaid the compliment,waiting until 1963 to adapt anyLovecraft tale to the screen (The Caseof Charles Dexter Ward), and even thenhiding it under an Edgar Allan Poe title(The Haunted Palace).Butunderground, appropriatelyenough, the two rivers blend. BothLovecraft and Laemmle drew theirarchetypes from the Gothic “terrortale” wellsprings of Shelley, Stoker, andStevenson. And both responded to, andreflected, the terrors characteristicof their times. Hence, Lovecraft’s retuning of the old horror standards,and the films’ “Silver Nitrate Gothic”blend of timeless legend and moderntension, can combine to throw a blackand-silver spotlight on the Mythos– or paint a Mythos shadow behindthe made-up monsters -- for Trail ofCthulhu gaming.Lovecraft Meetsthe Wolf Man“I may be able to bring you proofthat the superstition of yesterday canbecome the scientific reality of today.”-- Dr. Van Helsing, Dracula(Tod Browning, dir.)For all Lovecraft’s dismissal of the“childish folk-elements” of the previous7Lovecraft’s tales actually include twotraditional vampires. The monstrosity inthe basement of “The Shunned House”is a pseudo-scientific translation of thedisembodied blood-drinking spiritsof New England folklore; it absorbsthe entire personality and life-forceof its victims, and engages in a sort ofmesmeric possession similar to Lugosi’s(and Stoker’s) Dracula. The “vampiristicattacks” in The Case of Charles Dexter Wardare carried out by a “lean, lithe, leapingmonster with burning eyes whichfastened its teeth in the throat or upperarm and feasted ravenously.” To seal thedeal, this vampire is even the resurrectedcorpse of a black magician, namelyJoseph Curwen. Slightly widening ourexamination we find two more nearvampires. A different black magician,the witch Keziah Mason in “Dreams inthe Witch-House,” nurses her familiarBrown Jenkin on her own blood, “whichit sucked like a vampire.” (Brown Jenkinalso echoes the traditional vampire’sconnections to dreams and rats.) WilburWhateley’s twin, the invisible Son ofYog-Sothoth, fed on cattle “suckedmost dry o’ blood.” Other elements ofthe vampire recombine in the titular“Colour Out of Space,” which drainsthe life-energies of its victims and drives

TRAIL OF CTHULHUShadows Over Filmlandthem into Renfield-like madness, or evenin Cthulhu himself, a dead aristocratdreaming in his crypt and struck downby a wooden ship through the heart.The WerewolfLovecraft also directly adduces awerewolf legend in “The ShunnedHouse,” as part of the ancestry ofthe house’s vampire spirit, whichfurthermore takes on “wolfish shapes”in the smoke and possesses “wolfish andmocking” eyes. (The exceedingly minorLovecraft collaboration “The GhostEater” is a straight werewolf tale.) Onecan also read any of Lovecraft’s tales ofpossession, from “The Shadow Out ofTime” to Charles Dexter Ward (again) aswerewolf stories, stories of a humanbeing transformed into somethingbrutish against his will. On a still moresymbolic level, the act of being “bitten”by the Mythos curses unlucky or unwaryscholars with inhuman knowledge -- insome cases, such as Olmstead in “TheShadow Over Innsmouth,” leading tophysical transformation also. Finally,“The Hound” features a human sorcererchanged into an immortal caninemonster, complete with a grave-robbingscene the equal of anything from JamesWhale or Curt Siodmak.The Reanimated CorpseWhich leads us to the variousreanimated corpses of the 1930s’cinematic horrors, from White Zombieto Frankenstein. Lovecraft’s most famousFrankenstein is of course Herbert West,the Reanimator, whose story of hubrisand nemesis closely resembles those ofhis cinematic successors. On the literaryfront, Lovecraft’s titular “Outsider” is anagonized Gothic hero-corpse in the moldof Mary Shelley’s articulate Monster.Other revenants appear in Lovecraft,whether hinted (as in “The Statement ofRandolph Carter”), sidelined (as with thethings in the pits in Charles Dexter Ward),or inhuman (the thawed Elder Things inAt the Mountains of Madness).The MummyClosely related to the reanimatedcorpse is the immortal monster-magusembodied by Boris Karloff’s “Ardath Bey”in The Mummy. This is one of Lovecraft’sfavorite tropes. In “He,” “The TerribleOld Man,” “The Picture in the House,”“The High House in the Mist,” “Dreamsin the Witch-House,” and “The Thing onthe Doorstep” Lovecraft covers virtuallyall the immortality bases; the last evenincludes a romantic entanglement withthe immortal wizard. “The Festival”combines an immortal inhuman magusfigure with The Mummy’s trope ofreincarnations (or descendants) fallingvictim to ancient machinations.(The samevibe of primordial evil descending onmodern everymen is a core Lovecraftiansensation, perhaps most explicit in “TheShadow Out of Time.”) The undyingsorcerers of “Cool Air” and “The Horrorat Red Hook,” meanwhile, also have thatwhiff of Orientalism that makes TheMummy (and especially its sequels) sucha guilty pleasure. “The Nameless City”and “Under the Pyramids” add actualmummies to the mix along with theirArabian and Egyptian settings. “Out ofthe Aeons” may have the best Lovecraftianmummy per se, but surely the ghouls of“Pickman’s Model” and Dream-Quest ofUnknown Kadath are Lovecraft’s mostcharacteristic blends of the immortal,the magical, and the exotic.The Mad ScientistOn the other side of the reanimated corpseis the reanimator, or in larger terms, themad scientist, the “Henry Frankenstein.”In addition to Herbert West, Lovecraftpresents us with Crawford Tillinghast in“From Beyond,” Dr. Clarendon in “TheLast Test,” Dr. Munoz in “Cool Air,” themurderous entomologist Slauenwitein “Winged Death,” and perhaps eventhe electrical showman Nyarlathotep in“Nyarlathotep.” Although the inventorof the “cosmic radio” in “Beyond theWall of Sleep” is almost a sympatheticfigure, he could easily be played as amad experimenter on the insane andunfortunate. Symbolically, virtually all8of Lovecraft’s protagonists (especiallythe overwhelmingly academic laterones) are “mad scientists” exploring thefrontiers of Things Man Was Not MeantTo Know, and suffering for their hubris.The Old Dark HouseOne staple of 1930s horror films is the“old dark house,” which was alreadya cliché when James Whale campilyexalted it in The Old Dark House (1932).In its pure form, this location entraps theprotagonists, usually innocent travelersforced to take shelter, in the ongoingGothic story line of the house and itsinhabitants. (The house isn’t alwaysold, or even dark; in The Black Cat, it’s agleaming Modernist trophy.) Lovecraft’spurest Old Dark House is probably thede Russy mansion in “Medusa’s Coil,”complete with its overheated narrativeof curses and murder. To an extent,Lovecraft’s stories are exercises inwidening the Old Dark House. In “TheShadow Over Innsmouth” the whole townof Innsmouth is the “Old Dark House,”in At the Mountains of Madness Antarcticaenmeshes human protagonists in theongoing “family drama” representedby the primordial rivalry of the ElderThings and shoggoths, and such tales as“Call of Cthulhu” and “Shadow Out ofTime” hint that the entire world acrossgeological epochs is an Old Dark House,complete with Things penned up in theattic waiting to get loose.The Cursed Lineage“Legacy” sequels like Son of Dracula andSon of Frankenstein foreground the oldGothic horror concept of the cursedlineage, as do films like Cat People. Thisis another favorite Lovecraft trope,from “Arthur Jermyn” to “The DunwichHorror” to “The Festival” to Charles DexterWard. Sometimes the cursed lineage isentirely external to the hero, as in “TheShunned House” or “The Lurking Fear,”but more often it is intimately bound upin the protagonist’s self-hood, as in “TheShadow Over Innsmouth” or “The Ratsin the Walls.”

TRAIL OF CTHULHUDouble FeatureThe Haunted IslandFrom the Haiti of White Zombie andthe Saint-Sebastian of I Walked With AZombie to King Kong’s Skull Island, themysterious island (often jungled) wherethe monster dwells is another powerfulsymbol in cinematic 1930s horror.Likewise, Lovecraft used it powerfully, ifsurprisingly sparingly, in his own fiction.His emblematic “Monster Island” is ofcourse R’lyeh, the sunken island thatrises in “The Call of Cthulhu.” R’lyeh isprefigured by the island of “Dagon,” andby the sunken Atlantis in “The Temple.”The similarly haunted island of Muappears only in the “flashback sequence”of “Out of the Aeons,” and it’s probablypressing the point to claim that Australiarepresents a haunted island in “ShadowOut of Time.” Still more tangentially,this may be the context in which to notethat Lovecraft’s take on searching formysterious apes in the jungle, “ArthurJermyn,” like King Kong, touches oninterspecies romance, although Lovecraftforegrounds the issue and plays it forhorror rather than pathos.The Silver Nitrate Mythos“My friend said they were horribleand impressive beyond my mostfevered imaginings; that what wasthrown upon a screen in the darkenedroom prophesied things none butNyarlathotep dare prophesy ”-- H.P. Lovecraft,“Nyarlathotep”The themes of horror, like its images,often flow from the same well. Someelements, such as xenophobia, thedegenerate family, or the clash ofmodernity with the undead past,are traits of the literary Gothic, andemerge in Lovecraft as well as in theUniversal and RKO horrors. Likewise,the movies and the Mythos both sharecontemporary fears of the loss of theself (to werewolfism or Deep Oneblood), and share in the Frankensteininspired (or Faustian) fear of scienceand knowledge. In the age of Freud andHitler, of industrial change and globalwar, such fears naturally bubble up, incelluloid and in pulp.But other central themes of the 1930smonster movies do not immediatelyconform to Lovecraftian patterns. Forexample, as with conventional filmsof the era, virtually all of them involveromance, if only as a tacked-on subplot.Other concerns are more specificto Universal or RKO horror films.Accentuating those Silver Nitrate Gothicelements, which are often sublimatedor downright submerged in Lovecraft’stales, brings a whole new palette to aTrail of Cthulhu game -- Turner ClassicMovies instead of Weird Tales.Predatory and PervertedSexualityFrom the subtle simmer of I Walked WithA Zombie to the manic melodrama ofMummy’s Hand, the Silver Nitrate Gothicis all about sex. The monsters embodypredatory, even fatal, sexuality invirtually every case from the Wolf Man,cursed to kill the woman he loves, toKong, slain by beauty. Above and beyondthe simple horror of monster-humanmating, the sex on offer is perverse andsterile: Dracula’s oral fixation, Irina’srepression in Cat People, the Monster’spromise to Frankenstein to “be with youon your wedding night,” and its sequelwith two madmen giving birth to a newEve. It gets even more lurid just belowthe surface, from Kong’s bondage fetishto lesbian overtones in Dracula’s Daughterto necrophilia and incest in The BlackCat. Lovecraft’s horror-towns full ofmiscegenation and inbreeding hint aroundthe same territory, although his revisiontale “Medusa’s Coil” and to a lesser extent“The Thing on the Doorstep” are the onlyplaces where sexuality takes anythinglike the foreground. But the materialis there to be mined, if the Keeper and9players feel up to it. Simply putting asexual through-line in every scenario(whether central or secondary) willjuice the Mythos in unfamiliar directionsrich with roleplaying possibilities. Youdon’t even have to violate your players’personal Hays Code -- just hint andwhisper and suggest, like the scripts ofthe 1930s had to.PsychologyPerhaps appropriately for the great ageof Freudian film-making, the other greatobsession of the Silver Nitrate Gothic ispsychology. The Wolf Man begins with apsychological definition of lycanthropy,and much of Larry Talbot’s tormentcomes from believing himself insane.The trance phenomena in I Walked WithA Zombie can be explained as hypnosis,hysteria, or any other mental illness.The Boris Karloff film Bedlam is set inan 18th-century madhouse, and the1932 version of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde islikewise told in starkly Freudian terms,as the war of id and superego. In Ghostof Frankenstein, Ludwig Frankensteincombines his ancestor’s surgical interestswith a specialization in “diseases of themind,” making explicit the psychologicalinferences in the first film. (For instance,the Monster’s “abnormal brain” is thecreation of the 1931 scriptwriter, notMary Shelley.) The dubious Dr. Judd inVal Lewton’s 7th Victim and Cat Peopleis a psychologist, combining the VanHelsing-style “scholar-hero” with the“mad scientist.” For all Lovecraft’sobsession with insanity, very few of hischaracters really possess psychologicalmotivations (as opposed to nervous or“artistic” temperaments) of the sort that1930s film audiences would recognize.The younger Peaslee, in “Shadow Outof Time,” is HPL’s only importantpsychologist narrator; the Silver NitrateGothic has psychologists, pro andamateur, oozing out of every script.Keepers should work with the players’Drives to emphasize such concerns, anddraw NPCs’ mind-scapes in even starkerterms. Designing the landscape, or theweather, to reflect psychological strain

TRAIL OF CTHULHUShadows Over Filmland(or symbolism) is practically de rigeurfor the Gothic, whether Silver Nitrateor no.Corpses and MutilationFilm scholar David J. Skal proposesthat the memories of the First WorldWar, and the increasing fears of aSecond, lay behind the Universal films’propulsive interest in corpses, especiallymutilated corpses. From White Zombieto Frankenstein, the dead are everywhereon screen. Freaks and Island of LostSouls both feature mutilation and thegrotesque not merely as sudden shocks(as in the “unmasking” scene in Phantomof the Opera) but as ongoing themes, asdo arguably Bride of Frankenstein and theother sequels in that franchise. Whileearly tales such as “Herbert West –Reanimator” and “The Lurking Fear”both feature corpses and plenty of ‘em,Lovecraft’s body count dwindles as hisfiction gets more cosmic. (The arguableexception, At the Mountains of Madness,features multiple vivisections, albeitall at a remove.) Here, the explicitlyforensic nature of GUMSHOE can helpconvey that Silver Nitrate Gothic feel –describing the corpse in detail shouldprovide both clues and grue.Economic FearSkal also argues that the arrival ofthe horror film genre and the GreatDepression were not unconnected.Audiences, he says, sublimated andtransferred their economic fears intosupernatural terrors, expiated at leastmomentarily on the silver screen.Ann Darrow in King Kong, and MaryGibson in 7thVictim, both explicitly skirteconomic disaster before toppling intotheir respective horrors. Bela Lugosi canrepresent both predatory capitalism anddehumanizing Communism (dependingon the viewer) in both Dracula andWhite Zombie. In The Wolf Man, LarryTalbot adds class insecurity to his otheridentity problems – is he a middle-classAmerican or a British aristocrat? Classconflict is even more pronounced inother British-set films of the era, fromDr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde to The Body Snatcher toThe Lodger. Lovecraft’s greatest evocationof economic fear comes in “The ShadowOver Innsmouth,” featuring the devil’sbargain for prosperity with the DeepOnes, and its dismal outcome. Thatsaid, the stricken Gardners in “TheColour Out of Space,” and even theimpoverished urban victims in “Dreamsin the Witch-House” and “Haunter ofthe Dark” demonstrate that even themost reactionary of authors was notimmune from the economic currents ofthe Depression. Motivating Investigatorsby naked greed (or by desperation astheir obsession with the Mythos erodestheir Credit Rating) may or may notbe possible in any given campaign, buteconomic tension and despair can alwaysdrive NPCs to foolish or evil acts.BlasphemyThe Silver Nitrate Gothics seeminglyrejoice in blasphemy. Henry Frankensteinhas replaced both God and Adam, thereare Satanic cults in The Black Cat andThe 7th Victim, Count Dracula becomesRenfield’sinvertMessiah,andeverywherethe natural, Godly order is mocked.Conventional religion is almost nevershown in a sympathetic or helpful guise,but revealed only as the stark negative tothe horrors on screen. Again, for all thatLovecraft uses the term “blasphemous”to describe his monstrosities, religion isnot mocked so much as almost entirelyabsent in Lovecraft. (With the exceptionof the cuckoo’s egg cult of the StarryWisdom, nestled in the abandoned shellof a Providence church.) Where a Pulpidiom game might present crucifixes andholy water as suitable weapons againstthe undead, a Purist game can bringa church, or even all human religion,into the foreground as yet anothersymbolically mutilated corpse.RandomnessFinally, the Universal horrors aresurprisingly random. Becoming thereincarnated target of a mummy’spassion, or stumbling into an old darkhouse, or having a vampire as a next-door10neighbor, is almost always a matter ofpure chance. “Even a man who is pure ofheart,” after all, can become a werewolf.For all Lovecraft’s conceptualizing ofan arbitrary cosmos, virtually all of hisprotagonists invite their own doom,Frankenstein-style. Only the narrator of“The Picture in the House” (who takesa classic Old Dark House-style “shortcut”in a storm), the Gardner family struckdown by an almost literal bolt from theblue in “Colour Out of Space,” and theelder Peaslee in “Shadow Out of Time,”randomly selected by the Great Race ofYith, truly embody the random victim.The Keeper can emphasize such thingsby aiming the trail of clues toward thearbitrary cause rather than toward thevictim’s behavior, or simply by rollingdice to select the next victim in thenarrative thread.The End ?Even at their most arbitrary, the universalhorrors of the Silver Nitrate Gothics stillyield to a higher order. The monstersare defeated, usually by embodimentsof order, whether traditional (the mobof reactionary peasants), religious(crosses, hellish fire, or silver bullets),or dramatic (conventional human lovetriumphs over Dracula, the Mummy,and Kong). This happens more rarelyin Lovecraft -- “The Dunwich Horror,”“The Shunned House,” Charles DexterWard-- though it does happen. Most Trail ofCthulhu adventures will probably endlikewise. But in the Universal horrors,just like in Trail of Cthulhu campaigns,there’s always a sequel. There are alwaysmonsters surviving from the past, alwaysnew madmen playing God, alwaysdesperate fools waiting to be deceived.The world of the Silver Nitrate Gothic ismore Lovecraftian than we think.

TRAIL OF CTHULHUBACKLOT GOTHICEast Of Switzerland,West Of HellWhen the investigators travel to theBacklot Gothic setting, they’re leavingthe “hacked from the history books”world that is the default for Trail OfCthulhu and entering a nether regionthat is less a location than a literaryconceit. It is an eerie atmosphereevoked through wildly expressionisticvisuals, florid dialogue, and a sometimesdreamlike logic.The phrase “Backlot Gothic” is not aterm in use by characters in the world. Inthe movies that inspire it, sense of placeis deliberately obscured. Instead, theinvestigators might be told that they aretraveling to a “certain remote provincein the dark heart of Europe.” Sometimesa specific region will be identified—most notably Transylvania. More often,characters may refer to being situatedin a province or state but will neverstate where exactly they are. Culturalmarkers, from costumes to propernames, mix German, Swiss, Austrianelements with hints of Czechoslovakia,Hungary, and Romania. Amongst theseinfluences one also finds a heady streakof imaginary, Gothic-revival England.The characters of Backlot Gothic areaware of the rest of the world, makingreference to places like England andAmerica, but are detached from thehistorical horrors slowly tighteningtheir grip on it. Though a place ofmorbidity and doom, Backlot Gothicis also an escapist fantasy. It may bevery near to Austria, but you’ll findno swastikas, no Gestapo officers, andno Hitlerian oratory blazing from theradio.Dread AlbionOn certain nights, when the moon is full and the color drains from theland, some sections of the British Isles take on a terrible remoteness, displayingan unmistakable kinship to the Backlot Gothic setting. For a similar excursioninto celluloid horror on the Yorkshire moors or Scottish Highlands, strip outthe central European costumes, names and job titles, but keep the gloomyatmosphere, Gothic scene descriptions, and sense of arrested modernity.Downplay the technological restrictions that prevail in the Teutonic/Slavicversion of the setting. Automobiles ought to acceptable here, for example.Youdon’t have to resort to literary conceit to rule out tommy-guns, which arealready highly restricted throughout the country.For that matter, you’ll find no radio,as Backlot Gothic is curiously unstuckin time. Just as it blends culturalindicators from English, Teutonic andBalkan cultures, its chronological signposts are a hodge-podge ranging fromthe renaissance to the modern. Hereyou’ll find trains but no automobiles;instead the primary land conveyance isthe horse-drawn carriage. The hauntedbackwaters of Backlot Gothic entirelylack airstrips, landing fields, planes,or zeppelins. There are no radios ortelephones; investigators will have todo their legwork by physically travelingfrom the police station to the count’scastle and then down to city hall.Characters may wield luger pistolsbut never a tommy gun. The flashlightis unknown here; occasionally you’llsee a mob of villagers armed withlanterns, but the most popular sourceof nighttime illumination remains thetorch—that’s the flaming kind, notthe electric. Yet at the same time, thesetting’s secret laboratories spark andfizz with futuristic equipment borderingon the fantastical. A mad scientist mayequip his lair with impossible devices,such as a surveillance system whichrecords moving images of intrudersand broadcasts them to a viewing11screen—in simultaneous time! However,these remain alarming rarities—reasonalone for the townsfolk to storm thecastle, angry torches held aloft.Because Backlot Gothic is a literaryconceit, a collection of associationsand images meant to evoke a feelingof delicious and flamboyant dread, thecharacters remain unconscious of itsgeographical, stylistic, and temporaloddities. The players may make selfaware jokes about its various departuresfrom realism, but their characters neverquestion them. Like the NPCs, theynever stop to definitively locate theplace on a map, nor do they speak outloud the name of the country they’revisiting. Scenes of travel between thehistorical world and Backlot Gothic areelided, to avoid embarrassing questionsof when one reality ends and the otherbegins. The PC who habitually wieldsa tommy-gun now has no machine gunon his person and takes no onstagemeasures to acquire one. (If the playerinsists on trying to find one, you simplytell him that his attempts have failedand quickly move back to the storylineat hand.)

TRAIL OF CTHULHUShadows Over FilmlandAbsent TechnologiesStock FootageThe expressionistic horror movies of the 1930s make bold use of visuals toevoke their world of delicious dread. In the verbal medium of roleplaying,Keepers lack the full range of filmic devices at the disposal of film directors. Toconvey visual information, you must either show the players images, or engagein prose description. In the latter case, you might cue up brief snippets fromyour DVD collection, or find appropriate clips from Internet video sharing sites.Many groups find large sections of text read verbatim to be distancing, and tuneout after a few lines. That said, this setting, with its roots in classic literature,is particularly well suited to brief, well-placed moments of prose description.To that end, we’ve divided up what in another game book might be sections ofdescriptive text meant for the GM alone into blocks of text we’re calling “stockfootage.” Like the filmic equivalent, these are pieces of description ready todrop into a narrative context of your choosing. These can be used at appropriatemoments in any of the scenarios provided in this book, or in cases of your owndevising. For example, the description of train travel given on this page is suitedto the investigator’s first journey into Backlot Gothic, whatever that happens tobe in your campaign.Accordingly, we’ve written much of the description in this chapter in the secondperson, so that it not only tells you, the Keeper, what sort of visual images toassociate with it, but is packaged to allow you to convey these to the players.Paragraphs of stock footage are preceded by the identifying SF icon. They arepreceded by a brief descriptive tag, in boldface, so you can find them by quicklyscanning this chapter when needed. Stock footage passages are broken up intoshort passages; unless your group is unusually hungry for canned text, avoidreading more than one of them at once. The more sparingly you use them, themore powerful they’ll seem. Editing or paraphrasing the stock footage passagesas needed to fit the situation at hand.Stock footage can also create the illusion that the group is on the right track ina closely prepared adventure. This can be useful for groups who crave a sense ofstrong direction. For groups who fear railroading, show your hand, telling themthat the narrated passages float free from any pre-scripted storyline.You may find it useful to prepare for scenarios of your own creation by writingsections of stock footage tailored to them. The group may or may not ventureinto the old mill; if they don’t, you can always clip and save your old milldescription for a later case.When writing your own descriptions, subliminally drain this world of color.Omit mention of shades; instead, talk of light and dark, of shadows andgradations.Movie fans learn to recognize certain bits of overused stock footage. Unlessyou’re intentionally trying to underline the unreality of your game setting,you’ll want to avoid this effect, by ticking off the descriptions after using themfor the first time. Otherwise you might earn an unintended laugh by reusing amemorable bit of prose.Stock footage is another example of a GUMSHOE player-facing technique:it takes something normally reserved for the GM (in this case, backgrounddescription) and turns it around to face the players.12It’s easy enough to determinethat certain categories of item—including cars, planes, telephones,and flashlights—are unavailablehere. When certain items in acategory seem right and othersdon’t, the task becomes trickier.For example, the followingfirearms are not available:Nambu Type 14 pistol, WaltherP38 9mm, FN Browning High-Power9 mm, Smith & Wesson Model 27.357 Magnum revolver, ThompsonM1921 submachine gun, “Schmeisser”MP28 submachine gun.Guns are always rare. Even thelocal inspector may be unarmed.Members of the gentry likelypossess rifles and shotguns forhunting. The most sophisticatedmissile weapon fielded by mobs ofenraged townsfolk is the thrownrock. Most brandish farmingimplements: hoes, shovels, rakes,and, of course, pitchforks.On the other hand, dynamiteunquestionably exists here,and is accessible even by thepeasantry. They may threatento blow up haunted castles, orwreak explosive havoc duringa scenario’s final descent intomonstrous anarchy.When in doubt, resort to theoverall rule: if it doesn’t feel likeit would be in a classic 30’s horrormovie, it can’t be found in BacklotGothic, and its absence is not anissue to the people who live there.

1932 version of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde is likewise told in starkly Freudian terms, as the war of id and superego. In Ghost of Frankenstein, Ludwig Frankenstein combines his ancestor's surgical interests with a specialization in "diseases of the mind," making explicit the psychological inferences in the first film. (For instance,