Transcription

A few lines of reasoning can changethe way we see the world.Steven E. Landsburg{1}

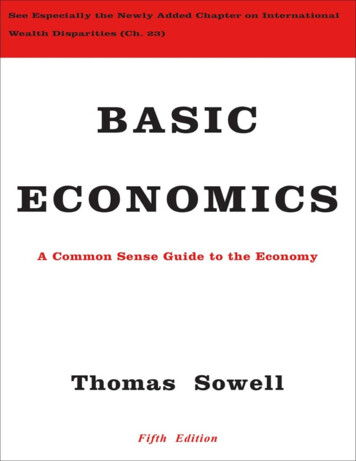

Copyright 2015 Thomas SowellPublished by Basic Books,A Member of the Perseus Books GroupAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever withoutwritten permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles andreviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY10107.Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in theUnited States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information,please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 ChestnutStreet, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mailspecial.markets@perseusbooks.com.Library of Congress Control Number: 2014945836ISBN: 978-0-465-05684-2

CONTENTSPrefaceAcknowledgmentsChapter 1: What Is Economics?PART I: PRICES AND MARKETSChapter 2: The Role of PricesChapter 3: Price ControlsChapter 4: An Overview of PricesPART II: INDUSTRY AND COMMERCEChapter 5: The Rise and Fall of BusinessesChapter 6: The Role of Profits–and LossesChapter 7: The Economics of Big BusinessChapter 8: Regulation and Anti-Trust LawsChapter 9: Market and Non-Market Economies

PART III: WORK AND PAYChapter 10: Productivity and PayChapter 11: Minimum Wage LawsChapter 12: Special Problems in Labor MarketsPART IV: TIME AND RISKChapter 13: InvestmentChapter 14: Stocks, Bonds and InsuranceChapter 15: Special Problems of Time and RiskPART V: THE NATIONAL ECONOMYChapter 16: National OutputChapter 17: Money and the Banking SystemChapter 18: Government FunctionsChapter 19: Government FinanceChapter 20: Special Problems in the NationalEconomyPART VI: THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMYChapter 21: International TradeChapter 22: International Transfers of WealthChapter 23: International Disparities in WealthPART VII: SPECIAL ECONOMIC ISSUES

Chapter 24: Myths About MarketsChapter 25: “Non-Economic” ValuesChapter 26: The History of EconomicsChapter 27: Parting ThoughtsQuestionsNotes

PREFACEThe most obvious difference between this book and otherintroductory economics books is that Basic Economics has no graphsor equations. It is also written in plain English, rather than in economicjargon, so that it can be readily understood by people with no previousknowledge of economics. This includes both the general public andbeginning students in economics.A less obvious, but important, feature of Basic Economics is that ituses real-life examples from countries around the world to makeeconomic principles vivid and memorable, in a way that graphs andequations might not. During the changes in its various editions, thefundamental idea behind Basic Economics has remained the same:Learning economics should be as uncomplicated as it is eye-opening.Readers’ continuing interest in these new editions at home, and agrowing number of translations into foreign languages overseas,{i}suggest that there is a widespread desire for this kind of introductionto economics, when it is presented in a readable way.Just as people do, this book has put on weight with the passingyears, as new chapters have been added and existing chaptersupdated and expanded to stay abreast of changing developments in

economies around the world.Readers who have been puzzled by the large disparities ineconomic development, and standards of living, among the nations ofthe world will find a new chapter—Chapter 23, the longest chapter inthe book—devoted to exploring geographic, demographic, culturaland other reasons why such striking disparities have existed for solong. It also examines factors which are said to have been major causesof international economic disparities and finds that the facts do notalways support such claims.Most of us are necessarily ignorant of many complex fields, frombotany to brain surgery. As a result, we simply do not attempt tooperate in, or comment on, those fields. However, every voter andevery politician that they vote for affects economic policies. We cannotopt out of economic issues and decisions. Our only options are to beinformed, uninformed, or misinformed, when making our choices onissues and candidates. Basic Economics is intended to make it easier tobe informed. The fundamental principles of economics are not hard tounderstand, but they are easy to forget, especially amid the headyrhetoric of politics and the media.In keeping with the nature of Basic Economics as an introductionto economics, jargon, graphs and equations have been left out.However, endnotes are included in this e-book, for those who maywish to check up on some of the surprising facts they will learn abouthere. For instructors who are using Basic Economics as a textbook intheir courses, or for parents who are homeschooling their children,more than a hundred questions are in the back of this book, with theprint book page numbers listed after each question, showing wherethe answer to that question can be found in the text.

THOMAS SOWELLHoover InstitutionStanford University

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSLike other books of mine, this one owes much to my twoextraordinary research assistants, Na Liu and Elizabeth Costa. Inaddition to their tracking down all sorts of information for me, Ms.Costa did the copy-editing and fact-checking of the manuscript, whichMs. Liu then converted into galleys and helped to index, after whichthe resulting Quark file was sent to the publisher, who could have thebook printed directly from her computer file. The chapter on thehistory of economics was read by distinguished emeritus ProfessorWilliam R. Allen of UCLA, a former colleague whose insightfulcomments and suggestions were very much appreciated, even when Idid not make full use of all of them. Needless to say, any errors orshortcomings that remain after all these people’s efforts can only bemy responsibility.And of course none of this would be possible without the supportof the Hoover Institution and the research facilities of StanfordUniversity.

Chapter 1

WHAT IS ECONOMICS?Whether one is a conservative or a radical, aprotectionist or a free trader, a cosmopolitan or anationalist, a churchman or a heathen, it is useful toknow the causes and consequences of economicphenomena.George J. Stigler{2}Economic events often make headlines in the newspapers or“breaking news” on television. Yet it is not always clear from thesenews stories what caused these particular events, much less whatfuture consequences can be expected.The underlying principles involved in most economic events areusually not very complicated in themselves, but the political rhetoricand economic jargon in which they are discussed can make theseevents seem murky. Yet the basic economic principles that wouldclarify what is happening may remain unknown to most of the publicand little understood by many in the media.These basic principles of economics apply around the world and

have applied over thousands of years of recorded history. They apply inmany very different kinds of economies—capitalist, socialist, feudal, orwhatever—and among a wide variety of peoples, cultures, andgovernments. Policies which led to rising price levels under Alexanderthe Great have led to rising price levels in America, thousands of yearslater. Rent control laws have led to a very similar set of consequences inCairo, Hong Kong, Stockholm, Melbourne, and New York. So havesimilar agricultural policies in India and in the European Unioncountries.We can begin the process of understanding economics by firstbeing clear as to what economics means. To know what economics is,we must first know what an economy is. Perhaps most of us think of aneconomy as a system for the production and distribution of the goodsand services we use in everyday life. That is true as far as it goes, but itdoes not go far enough.The Garden of Eden was a system for the production anddistribution of goods and services, but it was not an economy, becauseeverything was available in unlimited abundance. Without scarcity,there is no need to economize—and therefore no economics. Adistinguished British economist named Lionel Robbins gave a classicdefinition of economics:Economics is the study of the use of scarceresources which have alternative uses.SCARCITY

What does “scarce” mean? It means that what everybody wantsadds up to more than there is. This may seem like a simple thing, butits implications are often grossly misunderstood, even by highlyeducated people. For example, a feature article in the New York Timeslaid out the economic woes and worries of middle-class Americans—one of the most affluent groups of human beings ever to inhabit thisplanet. Although this story included a picture of a middle-classAmerican family in their own swimming pool, the main headline read:“The American Middle, Just Getting By.” Other headings in the articleincluded:Wishes Deferred and Plans UnmetGoals That Remain Just Out of SightDogged Saving and Some LuxuriesIn short, middle-class Americans’ desires exceed what they cancomfortably afford, even though what they already have would beconsidered unbelievable prosperity by people in many other countriesaround the world—or even by earlier generations of Americans. Yetboth they and the reporter regarded them as “just getting by” and aHarvard sociologist was quoted as saying “how budget-constrainedthese people really are.” But it is not something as man-made as abudget which constrains them: Reality constrains them. There hasnever been enough to satisfy everyone completely. That is the realconstraint. That is what scarcity means.The New York Times reported that one of these middle-classfamilies “got in over their heads in credit card spending” but then “gottheir finances in order.”“But if we make a wrong move,” Geraldine Frazier said, “the pressure we hadfrom the bills will come back, and that is painful.”{3}

To all these people—from academia and journalism, as well as themiddle-class people themselves—it apparently seemed strangesomehow that there should be such a thing as scarcity and that thisshould imply a need for both productive efforts on their part andpersonal responsibility in spending the resulting income. Yet nothinghas been more pervasive in the history of the human race than scarcityand all the requirements for economizing that go with scarcity.Regardless of our policies, practices, or institutions—whether theyare wise or unwise, noble or ignoble—there is simply not enough to goaround to satisfy all our desires to the fullest. “Unmet needs” areinherent in these circumstances, whether we have a capitalist, socialist,feudal, or other kind of economy. These various kinds of economies arejust different institutional ways of making trade-offs that areinescapable in any economy.PRODUCTIVITYEconomics is not just about dealing with the existing output ofgoods and services as consumers. It is also, and more fundamentally,about producing that output from scarce resources in the first place—turning inputs into output.In other words, economics studies the consequences of decisionsthat are made about the use of land, labor, capital and other resourcesthat go into producing the volume of output which determines acountry’s standard of living. Those decisions and their consequencescan be more important than the resources themselves, for there are

poor countries with rich natural resources and countries like Japan andSwitzerland with relatively few natural resources but high standards ofliving. The values of natural resources per capita in Uruguay andVenezuela are several times what they are in Japan and Switzerland,but real income per capita in Japan and Switzerland is more thandouble that of Uruguay and several times that of Venezuela.{4}Not only scarcity but also “alternative uses” are at the heart ofeconomics. If each resource had only one use, economics would bemuch simpler. But water can be used to produce ice or steam by itselfor innumerable mixtures and compounds in combination with otherthings. Similarly, from petroleum comes not only gasoline and heatingoil, but also plastics, asphalt and Vaseline. Iron ore can be used toproduce steel products ranging from paper clips to automobiles to theframeworks of skyscrapers.How much of each resource should be allocated to each of itsmany uses? Every economy has to answer that question, and each onedoes, in one way or another, efficiently or inefficiently. Doing soefficiently is what economics is about. Different kinds of economies areessentially different ways of making decisions about the allocation ofscarce resources—and those decisions have repercussions on the lifeof the whole society.During the days of the Soviet Union, for example, that country’sindustries used more electricity than American industries used, eventhough Soviet industries produced a smaller amount of output thanAmerican industries produced.{5} Such inefficiencies in turning inputsinto outputs translated into a lower standard of living, in a countryrichly endowed with natural resources—perhaps more richly endowedthan any other country in the world. Russia is, for example, one of the

few industrial nations that produces more oil than it consumes. But anabundance of resources does not automatically create an abundanceof goods.Efficiency in production—the rate at which inputs are turned intooutput—is not just some technicality that economists talk about. Itaffects the standard of living of whole societies. When visualizing thisprocess, it helps to think about the real things—the iron ore,petroleum, wood and other inputs that go into the production processand the furniture, food and automobiles that come out the other end—rather than think of economic decisions as being simply decisionsabout money. Although the word “economics” suggests money tosome people, for a society as a whole money is just an artificial deviceto get real things done. Otherwise, the government could make us allrich by simply printing more money. It is not money but the volume ofgoods and services which determines whether a country is povertystricken or prosperous.THE ROLE OF ECONOMICSAmong the misconceptions of economics is that it is somethingthat tells you how to make money or run a business or predict the upsand downs of the stock market. But economics is not personal financeor business administration, and predicting the ups and downs of thestock market has yet to be reduced to a dependable formula.When economists analyze prices, wages, profits, or theinternational balance of trade, for example, it is from the standpoint of

how decisions in various parts of the economy affect the allocation ofscarce resources in a way that raises or lowers the material standard ofliving of the people as a whole.Economics is not simply a topic on which to express opinions orvent emotions. It is a systematic study of cause and effect, showingwhat happens when you do specific things in specific ways. Ineconomic analysis, the methods used by a Marxist economist likeOskar Lange did not differ in any fundamental way from the methodsused by a conservative economist like Milton Friedman.{6} It is thesebasic economic principles that this book is about.One of the ways of understanding the consequences of economicdecisions is to look at them in terms of the incentives they create,rather than simply the goals they pursue. This means thatconsequences matter more than intentions—and not just theimmediate consequences, but also the longer run repercussions.Nothing is easier than to have good intentions but, without anunderstanding of how an economy works, good intentions can lead tocounterproductive, or even disastrous, consequences for a wholenation. Many, if not most, economic disasters have been a result ofpolicies intended to be beneficial—and these disasters could oftenhave been avoided if those who originated and supported suchpolicies had understood economics.While there are controversies in economics, as there are in science,this does not mean that the basic principles of economics are just amatter of opinion, any more than the basic principles of chemistry orphysics are just a matter of opinion. Einstein’s analysis of physics, forexample, was not just Einstein’s opinion, as the world discovered atHiroshima and Nagasaki. Economic reactions may not be as

spectacular or as tragic, as of a given day, but the worldwidedepression of the 1930s plunged millions of people into poverty, evenin the richest countries, producing malnutrition in countries withsurplus food, probably causing more deaths around the world thanthose at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.Conversely, when India and China—historically, two of thepoorest nations on earth—began in the late twentieth century tomake fundamental changes in their economic policies, theireconomies began growing dramatically. It has been estimated that 20million people in India rose out of destitution in a decade.{7} In China,the number of people living on a dollar a day or less fell from 374million—one third of the country’s population in 1990—to 128 millionby 2004,{8} now just 10 percent of a growing population. In other words,nearly a quarter of a billion Chinese were now better off as a result of achange in economic policy.Things like this are what make the study of economics important—and not just a matter of opinions or emotions. Economics is a tool ofcause and effect analysis, a body of tested knowledge—and principlesderived from that knowledge.Money doesn’t even have to be involved to make a decision beeconomic. When a military medical team arrives on a battlefield wheresoldiers have a variety of wounds, they are confronted with the classiceconomic problem of allocating scarce resources which havealternative uses. Almost never are there enough doctors, nurses, orparamedics to go around, nor enough medications. Some of thewounded are near death and have little chance of being saved, whileothers have a fighting chance if they get immediate care, and stillothers are only slightly wounded and will probably recover whether

they get immediate attention or not.If the medical team does not allocate its time and medicationsefficiently, some wounded soldiers will die needlessly, while time isbeing spent attending to others not as urgently in need of care or stillothers whose wounds are so devastating that they will probably die inspite of anything that can be done for them. It is an economic problem,though not a dime changes hands.Most of us hate even to think of having to make such choices.Indeed, as we have already seen, some middle-class Americans aredistressed at having to make much milder choices and trade-offs. Butlife does not ask us what we want. It presents us with options.Economics is one of the ways of trying to make the most of thoseoptions.

PART I:PRICES AND MARKETS

Chapter 2

THE ROLE OF PRICESThe wonder of markets is that they reconcile thechoices of myriad individuals.William Easterly{9}Since we know that the key task facing any economy is theallocation of scarce resources which have alternative uses, the nextquestion is: How does an economy do that?Different kinds of economies obviously do it differently. In a feudaleconomy, the lord of the manor simply told the people under himwhat to do and where he wanted resources put: Grow less barley andmore wheat, put fertilizer here, more hay there, drain the swamps. Itwas much the same story in twentieth century Communist societies,such as the Soviet Union, which organized a far more complex moderneconomy in much the same way, with the government issuing ordersfor a hydroelectric dam to be built on the Volga River, for so many tonsof steel to be produced in Siberia, so much wheat to be grown in theUkraine. By contrast, in a market economy coordinated by prices, thereis no one at the top to issue orders to control or coordinate activities

throughout the economy.How an incredibly complex, high-tech economy can operatewithout any central direction is baffling to many. The last President ofthe Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, is said to have asked British PrimeMinister Margaret Thatcher: “How do you see to it that people getfood?” The answer was that she didn’t. Prices did that. Moreover, theBritish people were better fed than people in the Soviet Union, eventhough the British have not produced enough food to feed themselvesin more than a century. Prices bring them food from other countries.Without the role of prices, imagine what a monumentalbureaucracy it would take to see to it that the city of London alone issupplied with the tons of food, of every variety, which it consumesevery day. Yet such an army of bureaucrats can be dispensed with—and the people that would be needed in such a bureaucracy can doproductive work elsewhere in the economy—because the simplemechanism of prices does the same job faster, cheaper and better.This is also true in China, where the Communists still run thegovernment but, by the early twenty-first century, were allowing freemarkets to operate in much of that country’s economy. Although Chinahas one-fifth of the total population of the world, it has only 10 percentof the world’s arable land, so feeding its people could continue to bethe critical problem that it once was, back in the days when recurringfamines took millions of lives each in China. Today prices attract foodto China from other countries:China’s food supplement is coming from abroad—from South America,the U.S. and Australia. This means prosperity for agricultural traders andprocessors like Archer Daniels Midland. They’re moving into China in all ofthe ways you’d expect in a 100 billion national market for processed foodthat’s growing more than 10% annually. It means a windfall for farmers in

the American Midwest, who are enjoying soybean prices that have risenabout two-thirds from what they were a year ago. It means a better dietfor the Chinese, who have raised their caloric intake by a third in the pastquarter-century.{10}Given the attractive power of prices, the American fried-chickencompany KFC was by the early twenty-first century making more salesin China than in the United States.{11} China’s per capita consumption ofdairy products nearly doubled in just five years.{12} A study estimatedthat one-fourth of the adults in China were overweight{13}—not a goodthing in itself, but a heartening development in a country onceafflicted with recurring famines.ECONOMIC DECISION-MAKINGThe fact that no given individual or set of individuals controls orcoordinates all the innumerable economic activities in a marketeconomy does not mean that these things just happen randomly orchaotically. Each consumer, producer, retailer, landlord, or workermakes individual transactions with other individuals on whateverterms they can mutually agree on. Prices convey those terms, not justto the particular individuals immediately involved but throughout thewhole economic system—and indeed, throughout the world. Ifsomeone else somewhere else has a better product or a lower price forthe same product or service, that fact gets conveyed and acted uponthrough prices, without any elected official or planning commissionhaving to issue orders to consumers or producers—indeed, faster thanany planners could assemble the information on which to base their

orders.If someone in Fiji figures out how to manufacture better shoes atlower costs, it will not be long before you are likely to see those shoeson sale at attractive prices in the United States or in India, or anywherein between. After the Second World War ended, Americans could beginbuying cameras from Japan, whether or not officials in Washingtonwere even aware at that time that the Japanese made cameras. Giventhat any modern economy has millions of products, it is too much toexpect the leaders of any country to even know what all thoseproducts are, much less know how much of each resource should beallocated to the production of each of those millions of products.Prices play a crucial role in determining how much of eachresource gets used where and how the resulting products gettransferred to millions of people. Yet this role is seldom understood bythe public and it is often disregarded entirely by politicians. PrimeMinister Margaret Thatcher in her memoirs said that MikhailGorbachev “had little understanding of economics,”{14} even though hewas at that time the leader of the largest nation on earth.Unfortunately, he was not unique in that regard. The same could besaid of many other national leaders around the world, in countrieslarge and small, democratic or undemocratic.In countries where prices coordinate economic activitiesautomatically, that lack of knowledge of economics does not matternearly as much as in countries where political leaders try to direct andcoordinate economic activities.Many people see prices as simply obstacles to their getting thethings they want. Those who would like to live in a beach-front home,for example, may abandon such plans when they discover how

extremely expensive beach-front property can be. But high prices arenot the reason we cannot all live in beach-front houses. On thecontrary, the inherent reality is that there are not nearly enough beachfront homes to go around, and prices simply convey that underlyingreality. When many people bid for a relatively few homes, those homesbecome very expensive because of supply and demand. But it is notthe prices that cause the scarcity. There would be the same scarcityunder feudalism or socialism or in a tribal society.If the government today were to come up with a “plan” for“universal access” to beach-front homes and put “caps” on the pricesthat could be charged for such property, that would not change theunderlying reality of the extremely high ratio of people to beach-frontland. With a given population and a given amount of beach-frontproperty, rationing without prices would have to take place bybureaucratic fiat, political favoritism or random chance—but therationing would still have to take place. Even if the government were todecree that beach-front homes were a “basic right” of all members ofsociety, that would still not change the underlying scarcity in theslightest.Prices are like messengers conveying news—sometimes badnews, in the case of beach-front property desired by far more peoplethan can possibly live at the beach, but often also good news. Forexample, computers have been getting both cheaper and better at avery rapid rate, as a result of technological advances. Yet the vastmajority of beneficiaries of those high-tech advances have not thefoggiest idea of just what specifically those technological changes are.But prices convey to them the end results—which are all that matterfor their own decision-making and their own enhanced productivity

and general well-being from using computers.Similarly, if vast new rich iron ore deposits were suddenlydiscovered somewhere, perhaps no more than one percent of thepopulation would be likely to be aware of it, but everyone woulddiscover that things made of steel were becoming cheaper. Peoplethinking of buying desks, for example, would discover that steel deskshad become more of a bargain compared to wooden desks and somewould undoubtedly change their minds as to which kind of desk topurchase because of that. The same would be true when comparingvarious other products made of steel to competing products made ofaluminum, copper, plastic, wood, or other materials. In short, pricechanges would enable a whole society—indeed, consumers aroundthe world—to adjust automatically to a greater abundance of knowniron ore deposits, even if 99 percent of those consumers were whollyunaware of the new discovery.Prices are not just ways of transferring money. Their primary role isto provide financial incentives to affect behavior in the use of resourcesand their resulting products. Prices not only guide consumers, theyguide producers as well. When all is said and done, producers cannotpossibly know what millions of different consumers want. All thatautomobile manufacturers, for example, know is that when theyproduce cars with a certain combination of features they can sell thosecars for a price that covers their production costs and leaves them aprofit, but when they manufacture cars with a different combination offeatures, these don’t sell as well. In order to get rid of the unsold cars,the sellers must cut the prices to whatever level is necessary to getthem off the dealers’ lots, even if that means taking a loss. Thealternative would be to take a bigger loss by not selling them at all.

Although a free market economic system is sometimes called aprofit system, it is in reality a profit-and-loss system—and the lossesare equally important for the efficiency of the economy, because lossestell producers what to stop doing—what to stop producing, where tostop putting resources, what to stop investing in. Losses force theproducers to stop producing what consumers don’t want. Withoutreally knowing why consumers like one set of features rather thananother, producers automatically produce more of what earns a profitand less of what is losing money. That amounts to producing what theconsumers want and stopping the production of what they don’t want.Although the producers are only looking out for themselves and theircompanies’ bottom line, nevertheless from the standpoint of theeconomy as a whole the society is using its scarce resources moreefficiently because decisions are guided by prices.Prices formed a worldwide web of communication long beforethere was an Internet. Prices connect you with anyone, anywhere inthe world where markets are allowed to operate freely, so that placeswith the lowest prices for particular goods can sell those goods aroundthe world. As a result, you can end up wearing shirts made in Malaysia,shoes produced in Italy, and slacks made in Canada, whi

13&'" & 5if nptu pcwjpvt ejõfsfodf cfuxffo uijt cppl boe puifs jouspevdupsz fdpopnjdt cpplt jt uibu #btjd&dpopnjdtibt op hsbqit psfrvbujpot *ujtbmtpxsjuufojoqmbjo&ohmjti sbuifsuibojofdpopnjd