Transcription

DOCUMENT RESUMEED 337 481TM 017 296AUTHORTI:LEHambleton, Ronald K.; Bollwark, JohnAdapting Tests for Use in Different Cultures:Technical Issues and Methods.PUB DATENOTEPUB TYPE9144p.Informaon AAalyses (070) -- Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142)EDRS PRICEDESCRIPTORSIDENTIFIERSMF01/PCO2 Plus Postage.Cultural Differences; Educational Assessment;English; Foreign Countries; Guidelines; Spanish; TestFormat; *Testing Problems; Test Validity;*TranslationScholastic Aptitude Test; *Test AdaptationsABSTRACTThe validity of results from internationalassessments depends on the correctness of the test translations. Ifthe tests presented in one language are more or less difficultbecause of the manner in which they are translated, the validity ofany interpretation of the results can be questioned. Many testtranslation methods exist in the literature, but most are ratherlimited in their appropriateness. This paper reviews the issues andmethods associated with test trEnslations or adaptations, andpresents some new results based on applications of item responsetheory (IRT) to establishing test guidelines. Guidelines are offeredfor establishing test equivalence based on a review of past studiesand current methods, particularly methods that involve double testtranslations and IRT methods. An example of translation equivalenceis drawn from the study by W. H. Angoff aAd L. L. Cook (1988) on theequating of English and Spanish versions af the Scholastic AptitudeTest. Two figures illustrate the discussion. A 33-item list ofreferences is included. **************************Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be madefrom the original ******************************

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION()bite t EduCatiOnal Research end improvementEDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATIONCENTER (ERIC)DY4is document Pas been reproduced 06received trOm trve person or Organizationoriginating itC, Minor Changes have been made tO improvereproduction dualityADAPTING TESTS FOR USE IN DIFFERENT CULTURES :TECHNICAL ISSUES AND METHODS1PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISMATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BYh,ofico1Ronald K. Hambleton, & John BollwarkUniversity of Massachusetts at AmherstTO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)."Points of view or opinions stated in mis (Jett,merit do not neCesSarilti represent officialOERI position or policyAbstrA2tIn recent years, there Las been considerable interest ininternational assessments of educational achievement.The validity ofthe results from these international assessments (such as the onerecently completed in several countrias in the areas of mathematics andscience) depends on the correctness of the test translations.If thetests presented in one language are more or less difficult because ofthe manner in which the tests are translated, the validity of anyinterpretations of the results can be questioned.Many test translationmethods currently exist in the literature, but most are rather Limitedin their appropriateness.In addition, the problem itself is one ofconsiderable difficulty.The purposes of this paper are to review the issues and methodsassociated with test translations or adaptations, to present some newresults based on applications of item response theory (IRT) toestablishing test equivalence, and to offer a set of guidelines forconuucting test translation studies based upon a review of past studiesand current promising methods, especially methods involving double testtranslations and IRT methods.1To appear in the Bulletin of the International Test Commission, 1991.LR20932 BEST COPY AVAILABLE

the testsAdapting tests for use in populations other than thoseof intelligencewere designed for has its roots in the beginningstesting.the potential ofPsychologists around the world readily sawselection purposes, andBinet's intelligence test for diagnostic andof interest.adapted it for use tn various populationsIn those firstdirect translation of thetest adaptations, the proess usually was atest.populations other thanMore recently, adapting tests for use infueled by an interest inthose for whom the test was designed has beenproviding a basis for cross-population comparisons.Researchersand other traitsinterested in quantifying differences in intelligenceadaptations.in different populations must rely on testAlso, ininitiatedcountries such as the United States, issues of test bias havethey are more relevant and thusan interest in adapting tests so that"fair' to specific segments of a particular population.The adaptationof transiating a test fromprocess in these cases should ideally consistgiven to the linguistic andone language to another, with considerationthe "equivalence" ofcultural relevance of the translated version and tothe different versions of the test.Validly translating a test from one language to another andtranslated versions isestablishing the equivalence of the original anda complex process.It is important that the process be betterincreasingly importantunderstood since test translations will play anrole in future testing activities.The main reason for this is that wemulticultural perspective andare increasingly viewing our world from atherefore there is a need to (1) understand the similarities andunbiaseddifferences that exist between populations and (2) provideLR2094

testing opportunities across different segments of a single population.Testing across populations provides a means for accomplishing thesegoals.For example, in 1988, the International Assessment of EducationalProgress (IAEP) was implemented (Lapointe, Mead, & Phillips, 1989).Thegoal of this project was to assess achievement in a common core ofscience and mathematics for 13-year-olds in fivet countries and fourCanadian provinces.In order to accomplish this goal, test items inEnglish were translated into several different languages.Alsoadministered were questionnaires regarding Jtudents' school experiencesand attitudes towards mathematics and science.This expensive and time-consuming assessment project was undertaken because the results provided potential insights into what aspectsof different populations influence the attainment of successfuleducational goals.One result from this study was that students fromthe United States scored lowest in mathematics achievement while Koreanstudents scored highest.these differences?What reason or reasons are responsible forAn answer to this question may be of substantial usein improving mathematics education in the United States and therefore isWithout cross-cultural assessmentof vital importance to our society.projects such as the IAEP, c'suers to these types of questions cannot beobtained.Without a proven methodology for evaluating the equivalenceof the original and translated assessment instruments, a valid basis forthese types of comparisons remains in question.The purposes of this paper are to provide an overview of languagetranslation of tests and inventories, and the methods used to establishtranslation equivalence.LR209The discussion that follows iocuses on tests5

is generalized towith the understanding that much of the discussionoccupational and interest inventories as well.discussed:The following topics arePresent(1) The Purposes of Test Translations, (2) Past andAssociated with TranslatingTrends of Test Translation Use, (3) ProblemsEquivalence, (5) ReviewTests, (4) Methods of Establishing TranslationModels in Establiehingand Selection of Methods5) Item ResponseEquivalenceTranslation Equivalence, and (7) Example of a TranslationStudy.Iht ParRualosianaDeveloping a test for use in a specific population can beaccomplished by either (1) developing the test within the culturalexistingboundaries of the population of interest or (2) translating antest so that it is appropriate for the population of interest.If thepurpose of developing a population-specific test is to reduce culturalbebias in the test scores, either one of the development methods maymethod use4; however, certain purposes require the use of the secondtest translation.is theThe first purpose that requires the use of test translationeconomical development of tests that are valid for use in specificpopulations or sub.populations.Some nations do not have qualifiedpersonnel available for test development and validation.In such cases,translating existing tests is the only viable alternative for testdevelopment.A second purpose that requires the use of test translation isproviding a basis for comparisons between populations (either distinctpopulations or within a population whose members' primary language orother cultural traits differ).LR209A recent example is the 19886

International Assessment of Educational Progress (IAEP).Thisassessment project required translating science and mathematics testitems from English to French, Korean, and Spanish in order to makecomparisons of achievement in these subjects across several populations(Lapointe, Mead, & Phillips, 1989).While both purposes for test translations are valid, it is thesecond purpose - cross-population comparisons - that are of particularinterest since test translations are the only alternative for allowingsuch comparisons.Nations lacking qualified personnel for testdevelopment may have the option of acquiring such expertise, thusreducing the need for test translations; however, those involved incross-population comparisons are more dependent on the use oftranslation techniques.The first test translated into another language was the BinetSimon intelligence test.Henry Goddard translated the test from Frenchto English in 1911 for use at the Vineland Training School for thementally retarded in New Jersey.By 1916, the Binet-Simon test had beentranslated into seven languages (Stanley & Hopkins, 1972).Since these early test translations, numerous tests have beentranslated into the primary language of the examinees to be tested.Some examples include the Otis Group Intelligence Scale, WechslerIn t ealldssm, and the Wechsler Adult IntelligenceScale.However, criticism of test translations has also paralleled theuse of this technique.Underlying much of the criticism were problemsin (a) establishing equivalence in vocabulary, (b) determining theLR2097

(c) culturaldominant language of target population examinees, anddifferences in responding to stimuli.Despite these criticisms, tests (and questionnaires/inventories)in target populations.are continually being translated for usereasons for this are clt.ar.TheFirst, the development of population-specific tests for certain purposes requires the use of testtranslations.Second, empirical studies support the use of testtranslations.Partial or total equivalence of translations have beenHansen andreported by, for example, Hulin, Drasgow, and Komocar (190);Fouad (1984); Hulin and Mayer (1986); Fouad and Hansen (1987); andCandell and Hulin (1986).For these two reasons, test translations havein thebecome an important aspect of test development work, particularlyareas of intelligence and aptitude tests.FS9.1212P-S-AUSigThe use of tests in populations other than thotle the test wasdesigned for has raised concerns since the beginnings of intelligencetesting (Samuda, 1983).In the case of test translations, it is assumedexist tothat enough differences between the populations of interestwarrant the development of a translated version of a test - it isidentifying these differences and incorporating solutions to minimizingthem that underlie many of the problems associated with translatingtests.Four problems,which will be considered next, are especiallyimportant.IlignIlfyln&Ang minipizinA Cultural Diftermus.An initial problem in the translation process is identifying thecultural differences between the source and target populations that mayaffect examinee test performance.LR209Among these cultural traits are8

examinee moUvation, values, experiences, and degree of test anxiei:y(van de Vijver & Poortinga, 1991).Cross-cultural researchers haveprovided numerous examples of how these cultural variables can influenceFor example, van de Vijver & Poortinga (1991)the testing process.point out difficulties experienced by Porteus in the administration ofthe Porteus Maze Test:for instance, found it difficult toPorteuspersuade Australian aboriginal subjects to solve the itemsby their own effort rather than in cooperation with theAs another example, it can be mentioned that thetester.Maze Test, which is a paper-and-pencil test, has beenapplied among groups from which the members had nevertouched a pencil before.This example, and others, though they do not deal directly withtest translations, points out that cultural differences between thesourct and target populations can affect examinee performance.It istherefore important to identify these cultural differences as a firststep towards minimizing these effects.A further complication is thatcultural differences must be considered for all parts of the testingprocess including test instructions, test items (content, responseformat, response mode, and symbol usage), administrator-examineeinteractions and testing environment (Berry & Lopez, 1977; van de Vijver& Poortinga, 1991).IdentifyinZ Itg Aparepriate Language for Teliling MIEgat ECIRUIALianExamineesProblems associated with identifying the appropriate language tobe used when testing examinees in the target population sometimes arise.Problems may arise because of varied dialects within the target language(Berry & Lopez, 1977; Clmedo, 1981).Olmedo (1981) noted:not uncommon to find that many tests written in formal Spanish are usedLR209

differentinappropriately with populations that speak substantiallySpanish dialects."Unless examinees are being tested on their abilitieszowith a formal language, at a minimum, even if translationstoaccommodate varied dialects are not being done, it is important(and whaz members ofidentiZy the dialects spoken in the target languageva:id test scorethe target population speak them) in order to maketnterpretations.language and testAn evun more complex problem associated withtranslations is determining the most appropriate language for testingbilingual target examinees.DeAvile and Havassy (1974) pointed outthatthat, because a person speaks a language, it can not be assumedthat languages/he can read and therefore be non-verbally tested in(neither can it be assumed that a person thl nks in that language).Moreover, a person may only be a functionally receptive bilingual.ForSpanish mayexample, "children from homes where parents prefer to speakthemselves be only funct!,onally xeceptive bilinguals.They mayunderstand Spanish but express themselves in English.The situationwith the parents may be ehe reverse" (01medo, 1981).These sittueel4n3point out the importance of understanding the extent of bilinguale-r ndits implications for testing in bilingual target examinees.,e;lure todetermine the most appropriate language for testing the targetpopulation can seriously undermine the validity of translating a testfrom the start.Finding BsimINA19 :RUALJNLAInumisA third problem associated with language and test translationsfinding, if they exist, words or phrases that are equivalent in thesource and target languages.For example, in a Spanish translation of(1LR20910P

the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory (II), Hansen and Fouad (1984) haddifficulties finding an equivalent Spanish translation for the Englishword "argument" (the authors report similar difficulties with sevenadditional items).In an attempt to alleviate the problem of non-equivalent words orphrases in the source and target languages, a process known asdecentering is sometimes used.Decentering refers to the modifying ofwords or phrases in either initially the source version of a test orlater, in both language versions of a test in order to achieve itemequivalence.For example, the Spanish word "paloma" is equivalent toeither "dove" or "pigeon" in English (Swanson & Watson, 1982) andtherefore a test item in English that requires making a distinctionbetween a dove and a pigeon would be difficult to translate intoSpanish.The original item in English could be decentered by using apair of terms that have similar meanings within the context of the item,and have eqtavalent terms in Spanish, thus allowing for a translation ofthe item.Hulin and Mayer (1986) pointed out, however, that decentering mayintroduce psychometric nonequivalence between the original andtranslated item:Decentering produces translated material with smooth andnatural terms in both versions. illt PliSALIUWLiar EatlItiguisticAchiorsicentered in either culture or language. Decentering shouldprnduce symmetrical translations with equal degrees offamiliarity, colloquialism, and idiosyncrasy in bothlanguages but fidelity to neither.The optimally decenteredversion, chosen through a mixture of back translations anddiscussions among translators, may introduce seriousquestions about psychometric equivalence between the twoversions. For instance, an English version of aquestionnaire that contained the phrase "Once in a bluemoon" (to describe the frequency of promotions) might resultin a decentered Spanish phrase, "Every time a bishop dies."LR209

Linguistically and ethnographically, the two versions aresmoothness, however,equivalent. The price of linguisticmay be paid in the coin of psychometric nonequivalence.Unfortunately, it is difficult to get a sense of the extent andtranslations fromappropriateness of decentering used in specific testoften report onlythe literature; descriptions of test translationswhether decentering was used or not.Useful information for evalu tinsof items decenteredthe decentering process might include the percentageaccomplished.and illustrative examples of how the decentering wanFinding Pompetent Translatorswith testLastly, there are also practical problems associatedtranslations.Translators familiar with the source and target languagetest can beand competent in the material covered by the sourcedifficult to find.The problem of finding competent translators becomescompounded when the test covers a specialized content domain (forexample, medicine).SummaryFour problems associated with translating tests have beendiscussed.The extent to which each of the four points is a problem intranslating a test will, of course, vary depending on thecharacteristics of the test and of the source and target populations.culturalFor example, it may be more difficult to identify and minimizethan a testdifferences for a test with a high degree of verbal loadingthat makes greater use of symbols.Moreover,the characteristics ofandthe source and target populations differ greatly, identifyingfor sourceminimizing cultural differences will be mor, difficult thanand target populations with similar or overl. Nr ng characteristics.Translating a test from one language to another an0 m,:intaining itsLR20912.1

validity with respect to a specific purpose can be an exceedinglycomplex process.Being aware of the many potential problems intranslating tests may help to minimize the errors associated with thetranslation process.Equivalence of test items is defined as the direct comparabilityof test items and the scores derived from them in terms of psychometricmeaning.Thus, test items are equivalent if they measure the samebehaviors across the populations of interest and examinees with equalamounts of ability within the populations have equal probabilities(within the limits of measurement error) of answering the itemscorrectly.A review of the literature on test aAd inve6toly translationsindicated that many different methods have been used to establish theequivalence between source and rranslated instruments.Some of themethods are more comronly used than others; however, a comprehensivereview of most or all of the available methods seemed useful.Thesemethods include those that are used both before and after examineeresponses have been collected.Each of the methods will be discussedmostly in terms of tests and test items with the understanding thatthese discussions generally apply to questionnaires and inventories aswell.The methods of establishing equivalence between original andtranslated test items can be v!.ewed as an extension of the methods usedfor identifying item bias.In bias studies, the focus is on the itemsor scores ierived from them for a single test.Establishing translationequivalence extends this focus to the items or scores derived from themLR209132

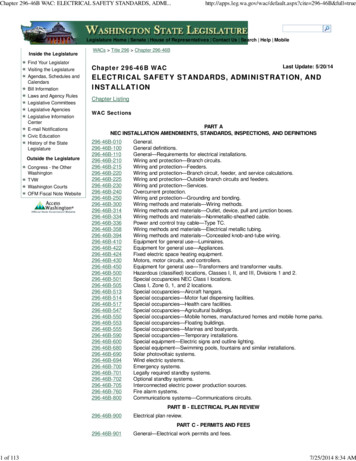

either the initial translation oron two tests - the original test andthe back translated version of the original test.The presence of moregives rise to thethan one version of a test on which to compare scoresbe discussed.various methods of establishing translation equivalence toMere is also a similarity in the methods used to establishtranslation equivalence and to identify biased items.In each case,used.both (a) judgmental and (b) statistical methods may beJudgmentalbased on a decisionmethods of establishing translation equivalence areby an individual or a group on the degree of each item's translationequivalence.In contrast, statistical methods establish translationequivalence based on the analysis of examinee responses to someitems.combination of the original, translated, or back translated testThe use of judgmental and statistical methods is not necessarilyindependent.Judgmental methods are often used as preliminary checks oftranslation equivalence before the tests are administered andstatistical methods applied to the test scores.ofThe classification scheme adopted for identifying methodswhetherestablishing translation equivalence in this paper is based onjudgmental or statistical methods are used.In addition, it is alsouseful to identify whether a single or back translation is used.Therefore, four categories of methods can be identified:1.AJudgmental single-translation methods1.BJudgmental back-translation methods2.AStatistical single-translation methods2.BStatistical back-translation methodsFigure 1 provides an overview of the current methods within each of thecategories.LR209These seven methods are considered next.1413

Insert Figure 1 about here./udgmftntal Math2AaAs stated previously, judgmental methods of establishingtranslation equivalence are based on a decision by an individual or agroup on the degree of each item's translation equivalence.Thus,judgmental methods provide a subjective viewpcint on the question ofequivalence.l.A.lPost-translation probes.In this method, one or moresamples of target examinees answer the translated version of an item andare then asked about the meaning of their answers.Evidence oftranslation equivalence is obtained if the responses given by a highpercentage of the examinees questioned reflect a reasonableinterpretation of an item in terms of cultural and linguisticunderstanding.The main judgmental aspect of this method is decidingwhat responses by target examinees about the meaning of their answer toan item are considered reasonable.The use of this method can provide valuable insights into why anitem did not successfully translate since examinees can be directlyasked about their interpretation of an item.This advantage crn,however, be offset by the interaction between the prober and theexaminee being questioned.Cultural, linguistic, and possiblypersonality differemes between the prober and examinee can interferewith the results obtained from the post-translation probe.A second problem with this method is that it is relatively laborintensive compared to many other judgmental methods.LR2091514In addition to

needed to answer test itemsenlisting and using probers, examinees areAdditionally, the probing process is likely toand respond to probes.be a time-consuming one.has to be sure of theA third problem with this method is that onemonolinguals in order tomeaning of the answers from source languagefrom target languagejudge the equivalence of the meaning of answersmonolinguals.in the sourceIn other words, the validity of the testresults from sourcepopulation must be fully checked before comparingand target examinees.For tests that have not undergone stringentthat havevalidity checks in the source population (for example, testsit may be useful tobeen developed for small scale research studies),probe a sample of source language monolinguals as well.This sample ofmonolinguals should be matched as closely as possible to targetexaminees on the ability or abilities of interest.With this additionalpossibly becheck, the problem of comparing irrelevant scores canavoided.1.A.2S11ingua2 judzes check for errors.This method makes useversions ofof bilingual judges who compare the source and translatedbetween translationseach test item and decide whether any differencespopulations ofcould result in non-equivalence of meaning in the twointerest (Brislin, 1970).These comparisons can be made on the basis ofhaving judges simply look the items over, check the characteristics ofthat may introducethe items against a checklist of item characteristicsnon-equivalence, or by having them attempt to answer both versions ofthe items before comparing them for errors.One problem in applying this method is that it is often difficultwith the source andto find bilingual judges who are equally familiarLR209

target languages and/or cultures.Therefore, judgments aboutdifferences between the source and translated versions are subject tovariations from this source of error.A second problem with this method is that bilingual judges mayinadvertently use "insightful guesses" to infer equivalence of meaning.This problem is usually raised in the context of using back-translationtechniques.Hulin (1987) noted:Apparently equivalent terms, such as amigo, friend andtovarish, Are not always equivalent, but translators sharinga small number of rules-of-thumb may consistently translatesuch terms as if they were equivalent. Equivalent sourcelanguage versions may be generated from poorly translatedand constructed target language versions by insightfulguesses and assumptions by the translators about what theterm must have ulant in the original language. Translationsthat retain grammatical forms of the original language areeasy to back-translate but may not be meaningful to targetlanguage monolinguals (Brislin, 1970).Judges are also translators of a sort and are subject to the sameerrors, in this case using "insightful guesses" to infer equivalence ofmeaning, as th, .D who performed the initial translation.A third problem with this method is that Lilingual judges may notthink about an item in the same way as .leir respective source andtarget language monolinguals.Consequently, the use of bilingual judgesto establish translation equivalence may lead to results that are notgeneralizable to source and target language monolinguals.This problemraises serious questions about the overall usefulness of this method forestablishing translation equivalence.1.A.3Performance criteria.This method of establishingtranslation equivalence is based on the criterion that "if people couldperform bodily movements after having heard either a source or targetlanguage instructions, and if the results of the bodily movementLR209171

and itscriterion were similar across all people, then the sourcetranslation must be equivalent" (Brislin, 1970).The obvious limitationmaterials thatof vhis method is that it can only be used with testingtest instructionscan be waluated through bodily movements such as someor performance test items.It isThe method has two other problems:(1) labor intenkive and (2) sensitive to prober-examinee interactions.1.B.1Sourca language monolinguals check for errata.Backtranslation refers to the translation of the target version test backinto the source version by bilinguals not involved in the originaltranslation in order to check for translation equivalence (Brislin,1970).Translation equivalence using this method is established byhaving source language monolinguals check for errors between the sourceand back-translated versions of a test (Brislin, 1970; Hulin & Mayer,1986; Hansen, 1987).The main problem associated with the use of this method is thereliance on the assumption that errors made during the originaltranslation will not be made again (in reverse) during back-translation.A translator may use "insightful guesses" or "rules-of-thumb" totranslate an item, thus making it appear equivalent to the source itemeven though it may not be.Likewise, the use of these "insightfulguesses" and "rules-of-thumb" during the back-translation process canmask those errors made during ehe original translation.Brislin (1970)reported finding errors due to translation after three successivetranslation/back-translation sequences, indicating that the assumptionthat the same errors that occurred in the original translation will notoccur, in reverse, during back translation is questionable.The use ofadditional (independent) translators may make it more likely thatLR209

differences in the original translation will be detected, but the highpotential for the violation of the previously mentioned assumptionreduces the usefulness of this technique and Any of the methodsdiscussed that are based on its use.Therefore, back-translating has problems, but it should beconsidered a general check on translation quality that will most likelydetect obvious errors in the original translation.For example, in aneffort to establish translation equivalence of a Spanish translation ofthe Job Descriptive Index, Hulin, Drasgow, and Komocar (1982) used theback-translation technique as an initial check of translation qualitybefore applying another method of establishing translation equivalence.Statistical MethodsThe three statistical methods to be discussed result fromvariations in (1) type of examinee responding (source languagemonolinguals, target language monolinguals, or source-target bilinguals)and (2) version

Since these early test translations, numerous tests have been translated into the primary language of the examinees to be tested. Some examples include the Otis Group Intelligence Scale, Wechsler. In_t_ealldssm, and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence. Scale. However, criticism of test translations has also paralleled the. use of this technique.

![[IRT] Item Response Theory - Stata](/img/54/irt.jpg)