Transcription

A publication of the COP26 Universities Network in cooperation withthe UCL Climate Action UnitCOMMUNICATINGCLIMATE RISKA HANDBOOKCommunicating climate risk: a handbook1

This document should be cited as:Roberts, De Meyer & Hubble-Rose, 2021. Communicating climate risk: a handbook, Climate ActionUnit, University College London. London, United Kingdom. DOI: 10.14324/000.rp.10137325This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licenseCopyrights are held by the authors listed above.Editor: Freya E. RobertsAuthors: Freya E. Roberts, Kris De Meyer & Lucy Hubble-RoseDesigner: Mary Anderson/Vitality Creative StudioAbout the UCL Climate Action UnitThe UCL Climate Action Unit works to change how scientists, policymakers, businesses, media, civilsociety organisations and citizens engage with each other about climate change. Its approach isunderpinned by a systems-based understanding of why organisations and individuals are not acting atthe scale and pace needed - and how this can be resolved.Learn moreAbout the COP26 Universities NetworkThis report is published by the COP26 Universities Network: a growing group of over80 UK universities and research centres working together to promote a zero carbon,resilient future. Its role is to ensure that the UK academic sector plays its role in deliveringa successful COP26.Learn moreAcknowledgementsThe UCL Climate Action Unit would like to thank members of the AU4DM Network whom wecollaborated with to deliver the communicating risk workshop:Martine J. Barons, Jo Lindsay Walton, Polina Levontin & Mark Workman.This handbook is released alongside a toolkit from the AU4DM network, which can be accessed here.Communicating climate risk: a handbook2

COMMUNICATINGCLIMATE RISKA HANDBOOKI.II.III.IV.V.VI.Risk for elephantsClimate risk theory of changeWriting hacksGolden nuggetsCrowd-sourced: questions to elicit end-users’ needsFurther reading, resources and references4-789-1011-1213-1415-17Ahead of COP26, experts from UK universities delivered a three day conference showcasingthe latest research on climate risk: the Climate Risk Summit (29 Sept-1 Oct 2021).The virtual Summit, funded and coordinated by the COP26 Universities Network, featured aninteractive workshop dedicated to the communication of climate risk. The UCL Climate ActionUnit delivered this communication workshop in partnership with the AU4DM Network; drawingon the interdisciplinary expertise of both teams.This handbook expands on the key ideas the UCL Climate Action Unit introduced to workshopparticipants. Its content is designed specifically for those working at the interface of climatescience and policy. This resource is for researchers and academics who want their work tohave an impact with policymakers.‘Communicating climate risk: a handbook’ explains insights from psychology andneuroscience on how our brains engage with the idea of climate risk, it highlights journalismhacks for writing about risk clearly, it shares lessons learned from the team’s experienceworking with policymakers on climate risk, and it offers a set of useful questions to help otherresearchers ascertain what policymakers need from climate risk research.It is a practical guide to communicating climate risk. The need for it has never been greater.Communicating climate risk: a handbook3

Risk for ElephantsThree insights from the sciencesof brain and mindImproving risk communicationInsightElephant and Rider: for people to ‘get’climate risk, speak to their elephantOur brains think in two qualitatively differentways: intuitive thinking and deliberativereasoning. Neither is necessarily right orwrong, nor necessarily rational or irrational.They coexist and are brought to the fore indifferent circumstances. A useful metaphorto understand how they interact is that ofan Elephant for the intuitive, automatic sideof our brains, and the much smaller Riderfor the deliberative side. Up to 95% or moreof what brains do is situated within theElephant, outside of conscious control andawareness. Conventional wisdom holds thatthe Rider – reasoning – is in control (or oughtto be). What the science shows, however, isthat the Elephant determines the direction oftravel most of the time. The Rider’s primaryrole is not to ‘think rationally’ (as commonlyassumed), but to rationalise and justify wherethe Elephant is heading.Elephant and Rider work together inevaluating situations of risk, but it is onlywhen our brains can evaluate a risk intuitivelythat we easily ‘get’ what the problem is. Whateach individual person processes intuitively(or not) is shaped by their prior experiencesand professional expertise. Any abstractissue (like climate change) or metric (likeaverage global temperature) can – over time– become internalised into our Elephants andacquire a ‘felt’ sense of risk. This happenswhen we become subject experts, or whenwe become passionately engaged with theissue. However, without the right exposure,abstract problems may not generate anyintuitive risk response at all. Becausescientists, policymakers and politicians aregoverned by their Elephants too, the sameapplies to them as does to all of us: particularrisks may ‘jump out’, while others do not. Fordecision makers, it is the risks that ‘jump out’that are of their primary concern. Risks thatdo not may leave them indifferent or make itmuch harder to grasp the problem.For people to ‘get’ climate risk, you haveto connect to their Elephant: try to linkthe hazard or impact you research to theconcerns which a particular target audiencealready understands (see ‘Risk currencies’,page 11). This means it’s a good idea to startwith listening to find out their concerns (see‘Focus on listening’, page 12).Communicating climate risk: a handbook4

Communicating risk effectively by connectingto people’s elephants is not necessarilythe same as scaring them. Fear is not aneffective or reliable driver of action, except forrunning away or hiding under a blanket. Tohighlight the distinction between intuitive riskevaluation and fear, consider this example:experienced medical staff dealing with anemergency may intuitively grasp the risksto a patient, but it doesn’t require them tobe scared before they’ll take action. On thecontrary, it’s unlikely you’ll want your doctor tobe panicking when they’re treating you!InsightGinger-the-Dog: what we think we sayis often not what other people hearthese abstract words, they can acquiredifferent intuitive meanings for our Elephantbrains. This often happens across differentdisciplines or sectors which have theirown practices and ways of working. Theconsequence is that, if you are speakingto someone with a different professionalbackground from your own, what you thinkyou are explaining is not what they mighthear. Here are 2 relevant examples:Uncertainty: for scientists, it may mean, e.g.,‘a measure of the spread in the data’; formost non-scientists (including policymakers)it means ‘being doubtful’ or ‘not knowing’. FarWorks Inc.Many abstract words and phrases lackmeaning or may have different meaningsfor different groups of people. Because wecannot point to concrete objects or eventsto calibrate our mutual understanding ofConservative risk estimate: for climatescientists, it usually means ‘erring on theside of least drama’; for risk analysts in otherdomains it may mean the opposite: ‘establishthe worst that can happen’. These opposingmeanings are rooted in different practices oferror avoidance: some domains or sectorsfocus on false positive avoidance (avoidingfalse alarms); others prioritise false negativeavoidance (avoiding something slippingthrough the net).Communicating climate risk: a handbook5

It doesn’t require much imagination to seethat Ginger can cause serious problems inthe cross-sector communication of climaterisk. Climate scientists have generally tried toavoid misunderstanding by providing rigorousdefinitions. However, because intuitive, feltmeanings reside in our Elephant brains,putting a definition at the top of a policy briefor on the first slide of a presentation will dolittle to resolve the problem. These unfamiliardefinitions address the Rider and may clashwith what’s inside your audience’s Elephant.The words will either pass over their heads(‘blah blah’) or may even lead to an ‘angryelephant’ charge and rejection.Through prolonged exposure, scientificdefinitions can become internalisedand become part of someone’s intuitiveunderstanding. Policymakers who workclosely with climate scientists may thus cometo share an intuitive understanding of thescientific language. But that simply shifts thecommunication problem down one station:those policymakers are now likely to run intoGinger problems of their own when speakingto people in other roles or departments.To communicate effectively, rather thanresorting to formal definitions, try to surfacedifferent meanings early on. Then findalternative ways to communicate in evocativeand descriptive language to bypass theGinger words. In other situations, it maybe more effective to change your practice.For example, climate scientists have longattempted to communicate the uncertaintyof climate change all the way down thepolicy chain. This has hindered rather thanhelped policy formulation and decisionmaking. Rather than communicating theuncertainty, it may be more effective to workwith your policymaker audience to ‘collapse’the uncertainty to point estimates whichare relevant for decision making, e.g., byselecting plausible worst-case values.InsightPyramid of Polarisation: ideas aboutclimate action are fragmentingThe forming and strengthening of an opinioncan be likened to starting at the top of apyramid and, tentatively at first, choosing oneside. As a loosely held opinion becomes morestrongly held through self-persuasion, wemove down the pyramid and progress everfurther from someone who took their first stepdown the other side. The more entrenchedour opinions become, the greater the degreeof rationalisation our Elephants will produce.Until a few years ago, this ‘pyramid ofpolarisation and self-persuasion’ wouldhave been most apt to make sense of thepolitical polarisation around questions like“Is climate change happening or not?”; “Is itman-made or not?” But with acceptance ofclimate change in society on the rise, andwithout any clear way out of the problem, itis increasingly driving an entrenching andfragmentation of opinion around how bestto communicate or act on climate change.Communicating climate risk: a handbook6

Although the disagreements which followfrom this opinion fragmentation are subtlerthan the older divisions between ‘sceptics’and ‘believers’, the consequences are noless pernicious. You may find yourself in aroom full of people who all agree that climatechange requires urgent action, but who aredeeply divided on the best strategy forward:Do our warnings of climate risk need tobe starker or not? Do we need to focus onindividual behaviour change, a carbon tax,or government regulation? Do we neednature-based solutions, renewables, nuclearenergy, carbon capture and storage, orshould we start looking into large-scale geoengineering? Is it still meaningful to act,or should we give up and focus on deepadaptation? Can we pull off the requiredtransformation within the current economicsystem, or should we overthrow capitalism?Paradoxically, the higher the concern insociety about climate change, the morewidespread this fragmentation could become.The main consequence of this is that riskinformation alone will be insufficient to drivecoherent policy action. What we will needin addition are credible and achievablepolicy and action pathways and a process ofsupport-building to deliver them.And if you find yourself in a heated debatewith someone who shares your view thatclimate change is a serious problem, butdoesn’t agree on what to do or how tocommunicate about it – try to step awayfrom that particular pyramid. Look not forthe middle but the common ground: thata plurality of solutions is needed, and thatmany of the ideas we have are not mutuallyexclusive. Together they could add up to thetransformation society will need to make.Communicating climate risk: a handbook7

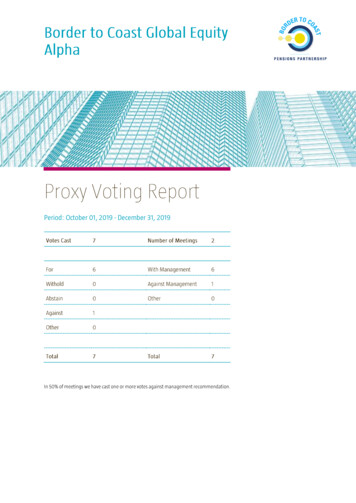

Climate RiskOur InsightsProblemIneffective translation ofscience into policyUnderstanding of the gaps inclimate risk managementProtagonistsScientists / AnalystsBrain InsightsCross-sector co-productionand facilitation skillsResearch FundersOutcomesDecision Makers in Policy,Finance and Businessscientists communicateclimate risk differentlydecision makers better equipped to ask theright questions of the science communityresearch funding better alignedto decision makers’ needsLong-Term Changesbetter application of risk managementleading to more effective climate policiesnew decision supportstructures and institutionsCommunicating climate risk: the handbooka culture shift in how scientistsand decision makers collaborate8

Writing hacksTips from science journalismEnsuring your content is clear and concise1Ask ‘so what?’When you write about your research, ask yourself ‘so what?’. By this we mean: why is thisimportant, how does this impact people or why should a decision maker care?Make sure what you have to tell them relates to the things they care about (economicstability, jobs, public health etc.).You may need to ask ‘so what?’ several times to really articulate why your researchmatters to people.‘So what’ is a really useful tool to help you identify your main message.2Think sentence lengthKeep sentences short wherever possible. Remember that your reader is a non-specialiston the subject and probably quite rushed. Make reading your work easy for them.Each sentence should communicate just one idea, or join together several related ideas.3Select your sentence structureChoose your sentence structure intentionally. If you can’t do that as you are writing, do itwhen you are editing your work.Simple sentenceshave one subject andone statementCompound sentenceshave two simple sentences joinedtogether with a conjunctione.g. “Green plantsproduce oxygen fromcarbon dioxide.”e.g. “Green plants produce oxygen fromcarbon dioxide and they removepollutants from the air.”Complex sentenceshave a main statementplus one or morequalifying statementsComplex-compound sentenceshave several main statements, eachwith their own qualifying statements,joined togethere.g. “Green plants,through a process calledphotosynthesis, produce oxygenfrom carbon dioxide.”e.g. “Green plants, through a processcalled photosynthesis, produce oxygenfrom carbon dioxide and remove pollutants,especially particulate matter, from the air.”Communicating climate risk: a handbook9

Complex-compound sentences are widely used in scientific literature but they canbe difficult to follow, so use this sentence structure sparingly. Aim for simplesentences wherever possible.4Avoid repetitionFind repetition in your writing and remove it. Do this as routinely as you wouldperform a spell-check.You might find repetition within a sentence: for example you may use two adjectives oradverbs where one is enough.Repetition can also occur in subsequent sentences: you may explain the samething twice but using different words. In this situation, pick whichever description is mostconcise and lose the other.Finally, check for repetition across paragraphs: you may have repeatedly written a nounout in full where you could have used a pronoun.5Use the active voiceUsing the active voice can be tricky to get your head around, but it will make your writingmore concise and direct. The active voice clearly states who or what does an action.There is a basic formula for writing a sentence in the active voice:subject verb statement active voiceStill a bit confused? Here’s an example:“Forest fires burned thousands of homes across the city this summer.”Here forest fires are the subject, and burning is the verb.It is sometimes appropriate to use the passive voice, but don’t do it just because you thinkit sounds a bit fancy. A good rule of thumb? Try to put the majority of your sentences in theactive voice, unless you really can’t write it any other way.6Apply the inverted pyramidIn short; put the conclusion at the start of your work.Your first few sentences need to tell the reader what your main point is and why theyshould care. You may not have the reader’s attention for long if they are in a hurry so getyour point across straight away. If they are hooked, they will read on to find out the details.Arrange details from most to least important in the subsequent paragraphs.Communicating climate risk: a handbook10

Golden NuggetsCommunicating with policymakersUnderstanding the space in which youwant to communicateThere is always a‘policy mood music’The policy mood music is a set of implicitassumptions and mindsets held by policyexperts about climate change. They appearself-evident to the people holding them, butmight actually be unfounded. Here are somerecent examples of the policy mood musicthat we’ve encountered: “Integrating renewables into the energysystem will be difficult and expensive” “Net Zero pledges by 2050-2060 areenough to take care of the problem” “We can adapt to the climate risks we’llsee in the next few decades”The policy mood music shifts over time. Itmay differ significantly depending on thecountry or sector you work with.What you want to communicate will either bein tune with the mood music or will challengeit. In the latter case, you are likely to meetresistance and be misunderstood. This isnot wilfullly, but because your message goesagainst the conventional wisdom. In thosesituations, test different ways of framing yourmessage with your target audience. This willallow you to identify which framings are leastlikely to lead to misunderstanding.Risk currenciesEvery policymaker has one or more risk‘currencies’: risks which are of primaryconcern to them. These are risks theyunderstand automatically and intuitively (see“Risk for Elephants’ on page 4). Commonrisk currencies you might encounter are:jobs, economic growth, migration numbers,national security and international relations.Most climate risk information is presentedin currencies which policymakers do notunderstand intuitively. Want to ensure yourresearch lands with your target audience?Find out the risk currency of the policymakersyou want to engage with, and then express orlink your messaging as closely as possible tothat currency.Climate risk informationdoes not automaticallydrive policy actionMost international policymakers taking part inthe COP process already know that climatechange is a serious problem. Yet this doesnot help them to know how to act on it. “Weknow the situation is bad, but what more canwe do?” is a question we frequently hear.The available information on climate riskgets across that the situation is dire, butdoesn’t get the policymaker any closer tounderstanding what to do about it. Theremedy is to collaborate with policymakersand experts in other domains to identify whatpolicy levers are available to address therisks your work highlights.Communicating climate risk: a handbook11

Adjust to the time constraintsof policymakersOutcomes and structureWithin academia, workshops and meetingscan last from a few hours to several days.In the world of policymakers, meetings areusually 1 to 2 hours long. The more seniora policymaker, the less likely you’ll be ablemeet with them for longer.No matter how intelligent the policy usersof your research are, simply bringing themtogether in a room with risk researchers willusually not work. Without a structured way forthe two groups to engage, the outcomes arelikely to be poor.When planning science-policy co-productionactivities, consider designing these asmultiple, short interactions. Each one couldbe with different groups of policymakers.Look at these repeated interactions as anopportunity: you have several chances torefine your understanding of what their needsare and what their risk currency is.You can avoid this by planning yourinteraction in advance. Determine firstwhat outcomes you want to achieve froma meeting, then create a structure ofinteractions with your participants that fulfillthose outcomes. Think beyond the usualacademic formats of presentations and paneldiscussions. Instead plan interactive sessionswhich focus on listening and understandingtheir risk currencies and the current policymood music.Focus on listening ratherthan broadcastingIn the limited amount of time you may getwith policymakers, prioritise ‘listening’ over‘broadcasting information’. Understandingwhat they need is the best use of that timebecause it will show you what to do to makeyour outputs more useful and usable.Designing such sessions, and formulating theright questions to ask, are skills in their ownright. Because of this, work with experiencedfacilitators to make your science-policyinteractions as effective as possible.Doing so allows you to avoid the ‘So what?’question; where prospective end users ofyour research fail to see how it connects totheir own risk currencies. If this happens, theywill not engage with it.Communicating climate risk: a handbook12

Crowd-sourced: questionsto elicit end-users’ needsAll researchers want their findings to have impact. For climate researchers, that usuallymeans delivering benefits to society and the natural environment. For research to benefitsociety, academics need to communicate what they know to someone who could use that riskinformation as part of a decision-making process. We call this person their end-user.That communication doesn’t happen just by putting researchers and decision makers in aroom together. A structured process is needed to enable each party to work out what the otherneeds and can give. The process happens through several rounds of dialogue.The goal of the conversation, for the researcher, is to really understand the decision-maker’sperspective. That means finding out what challenges the end user faces, what needs they feelthey have, and what objectives that they are trying to achieve.Directly asking ‘what do you need?’ may not lead to very deep, considered responses.Additionally, decision makers may not know what they need to know (the unknownunknowns).Instead, researchers can ask a variety of questions; the answers to which will help youelicit what an end-user really needs. Below is a list of questions we recommend building aconversation around.Once this information has been collected, a researcher can then analyse what they haveheard - looking for recurring themes and clear dos & don’ts. This enables them to determinewhat information their end-user will want to hear. The final job for the researcher is then toframe their findings in a way which addresses those needs.What is your greatest/mostimmediate concern?What are the sorts of problems that you needto solve and what criteria do you base yourdecisions making on?Describe an average dayconducting your work.What are you concerned about?What is your dream outcome; how do weget you there?How has your work changed in thelast 5/10 years?Tell me about a recent project where yousuccessfully made change happen.What would success look like(over 6/12/60 months)?Which of the challenges you facekeeps you awake at night / takesup most headspace?What are your organisation’s immediateconcerns or priorities?What strategic challenges do you face?Communicating climate risk: a handbook13

Explain a decision you made recentlywhere you considered climate risk.Who do you feel is most influentialwithin your organisation?Can you think of a challenge that madeyou rethink your goals?Name one thing that’s stopping youat the moment?What do you believe your boundaries arefor the problem you are trying to solve?How do you keep yourstakeholders happy?What are you trying to achieve? Whatprocesses are you using and who are youworking with to do this? These all wouldbe followed by why.What decisions that you need to make mightbe informed by weather/ climate information?How do you hope to use this data?Have you considered what would makeyou fail in your objectives?As a senior leader or manager, whatdo you consider to be your coreresponsibility regarding the organisation?Who would you trust to ask for informationabout the environment or related issues?How is information sharedin your organisation?What challenges do you routinely face andhow do you overcome these?How do you use academic research inyour day to day work to help youachieve your goals?What do you most desire fromclimate research?What areas or decisions of youreveryday work feel most unconnected toclimate change?What do you base your decisions on?What’s the worst thingthat could happen?What does your organisation do best?Can you tell me a little bit about your currentprojects to make change happen?Communicating climate risk: a handbook14

Further reading, resourcesand referencesRisk for Elephants: insights fromthe sciences of brain and mindElephant and Rider: not 1 type of thinking but 2Resources for non-specialists Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind is the origin of the Elephant and Rider metaphor.Learn more It is similar to Daniel Kahneman’s System 1/System 2 description of intuitive thinkingand deliberative reasoning in Thinking, Fast and Slow.Learn moreAcademic sources on risk perception Dual-process theories of cognition - the formal jargon for Elephant and Rider - featureextensively in psychologists’ study of risk perception. A good entry point into thisliterature is Slovic et al. (2010) The Feeling of Risk.Learn more A brief comment applying the ‘risk-as-intuitive-evaluation’ idea to climate risk:De Meyer, K. (2019) Geosci. Commun. Discuss. DOI: 10.5194/gc-2019-1-SC1Learn more The rationale for the idea that scientists and policymakers should collaborate to‘collapse’ the uncertainty around decision-relevant quantities - rather than try tocommunicate uncertainty down the decision or policy chain - is explained in:De Meyer, K. (2018) Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss. DOI: 10.5194/esd-2018-36-SC6Learn moreCommunicating climate risk: a handbook15

Ginger-the-dog and the intuitive meaning of wordsResources for non-specialists Ginger-the-dog - as we apply to climate change - is a specific instance of a recurringproblem throughout history: how language breaks down when terms become instilledwith different meanings. The consequences for politics and society are explored in MarkThompson’s book Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics?Learn moreThe pyramid of polarisation and self-persuasionResources for non-specialists The Analogy of the Pyramid stems from Carol Tavris’s and Elliot Aronson’s bookMistakes Were Made (but not by me) (there is a 3rd edition, updated in 2020).Learn more How this translates into the polarisation of public opinion on many pressing societalissues is explained in Kris De Meyer’s TEDxLondon talk The Genie of Polarisation.Learn moreOther insightsShifting the focus from risk to actionAlthough communicating climate risk information for specific decision-making contexts isnecessary, the pyramid analogy and its consequences indicate that - on its own - climate riskinformation will not drive policy and action. What is the alternative? Building people’s capacityfor action. How to do this is explored in: De Meyer et al. (2020) Environ. Res. Lett. DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/abcd5aLearn more TEDxLondon Climate Curious podcast with Kris De Meyer: Why there is more to climateaction than changing your carbon footprint.Learn moreCommunicating climate risk: a handbook16

Engaging with your end users Sharpe, 2019. Geosci. Commun. DOI 10.5194/gc-2-95-2019An editorial in which two experienced scientists discuss how researchers can contribute tosociety through science communication.Learn more Rapley & Lubchenko, 2020. Environ. Res. Letters. DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/abba9cAn article which underscores precisely why scientists should engage with decisionmakers before conducting research: so that they can present information in a way that theaudience can understand.Learn moreWriting for decision makersBooksEither of these books will help you to write clearly and concisely. Their pages contain lots ofbrilliant writing hacks. Evans, H. (2018) Do I Make Myself Clear? Why Writing Well Matters Evans, H. & Gillan, C. (2000) Essential English for Journalists, Editors and WritersOnline resources Refer to this incredibly comprehensive toolkit, authored by UCL Public Policy, for tips onhow to engage with policymakers as an academic.Learn more Troubleshoot grammar and style queries using this alphabetised treasure trove.Learn more Get support and skills-based training on writing for the media (and other lay audiences)from the Science Media Centre.Learn mateactionunit@ucl.ac.uk@UCL CAU

Unit, University College London. London, United Kingdom. DOI: 10.14324/000.rp.10137325 . a handbook' explains insights from psychology and neuroscience on how our brains engage with the idea of climate risk, it highlights journalism . Elephant and Rider: for people to 'get' climate risk, speak to their elephant