Transcription

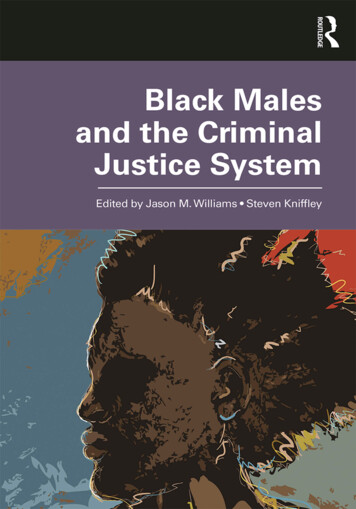

BLACK MALES AND THE CRIMINALJUSTICE SYSTEMRelying on a multidisciplinary framework of inquiry and critical perspective, this editedvolume addresses the unique experiences of Black males within various stages of contact in thecriminal justice system. It provides a comprehensive overview of the administration of justice,the mental and physical health issues faced by Black males, and reintegration into society aftersystem involvement.Recent events—including but by no means limited to the shootings of unarmed Black menby police in Ferguson, Missouri; Baltimore; Minneapolis; and Chicago—have highlighted thedisproportionate likelihood of young Black males to encounter the criminal justice system.Black Males and the Criminal Justice System provides a theoretical and empirical review of theneed for an intersectional understanding of Black male experiences and outcomes within thecriminal justice system. The intersectional approach, which posits that outcomes of societalexperiences are determined by the way the interconnected identities of individuals are perceived and responded to by others, is key to recognizing the various forms of oppression thatBlack males experience, and the impact these experiences have on them and their families.This book is intended for students and scholars in criminology, criminal justice, sociology,race/ethnic studies, legal studies, psychology, and African American Studies, and will serve asa reference for researchers who wish to utilize a progressive theoretical approach to studysocial control, policing, and the criminal justice system.Jason M. Williams is an Assistant Professor of Justice Studies at Montclair State University.His areas of expertise are race and justice, policing, social control, radical criminology, and thesociology of criminological knowledge. In addition to publishing on the above topics he iscurrently conducting qualitative research on Black males and reentry, urban youth andpolicing, and pedagogical-based research around the construction and dissemination of criminological knowledge and its impact on racialized students.Steven Kniffley is the Associate Director for the Center for Behavioral Health and an Assistant Professor in Spalding University’s School of Professional Psychology. He currently teachesMulticultural Psychology and Intro to Psychotherapy. Dr. Kniffley is also a Board CertifiedClinical Psychologist. Dr. Kniffley’s area of expertise is research and clinical work with Blackmales. Specifically, his work focuses on understanding and developing culturally appropriateinterventions for Black male psychopathology as well as barriers to academic success for thispopulation. Dr. Kniffley has written numerous books, book chapters, and articles on Blackmale mental health, Black males and the criminal justice system, and academic achievement.

“By examining the plight of Black males as perennial victims of state violence, this excellentcollection of essays serves as a corrective for the often racist and iconic image of the Black maleas incorrigible criminal.”Darnell F. Hawkins, PhD,Professor Emeritus, University of Illinois at Chicago“These outstanding editors and brilliant authors of Black Males and the Criminal Justice System provide a definitive and compelling examination of the historical and contemporary challenges forBlack males in the most draconian carceral system in the world. Few texts on the intersection ofBlack males and the criminal justice system illuminate such a comprehensive interdisciplinarysociological, criminological, public health, social work, public policy and social justice approachto analyze structural violence, disproportionate minority contact, collateral consequences, and lifeoutcomes among Black men involved in the criminal justice system. I congratulate and applaudDrs. Williams and Kniffley for their incredibly sophisticated analysis of the most pressing civiland human rights issue for Black males in the 21st century.”Joseph B. Richardson, Jr., PhD,Professor, University of Maryland College Park

BLACK MALES AND THECRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMEdited by Jason M. Williams and Steven Kniffley

First published 2020by Routledge52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017and by Routledge2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RNRoutledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business 2020 Taylor & FrancisThe right of Jason M. Williams and Steven Kniffley to be identified as the authors of theeditorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted inaccordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in anyform or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system,without permission in writing from the publishers.Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks,and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Williams, Jason M., 1986- editor. Kniffley, Steven, Jr., 1985- editor.Title: Black males and the criminal justice system / [edited by] Jason M. Williams &Steven Kniffley.Description: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2019.Identifiers: LCCN 2019010328 (print) LCCN 2019011754 (ebook) ISBN 9781315522012 (Ebook) ISBN 9781138697355 (hardback) ISBN9781138697362 (pbk.)Subjects: LCSH: Discrimination in criminal justice administration–United States. African American men–Social conditions. African American prisoners. AfricanAmerican criminals–Rehabilitation. United States–Race relations.Classification: LCC HV9950 (ebook) LCC HV9950 .B525 2019 (print) DDC 364.3/7308996073–dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010328ISBN: 978-1-138-69735-5 (hbk)ISBN: 978-1-138-69736-2 (pbk)ISBN: 978-1-315-52201-2 (ebk)Typeset in Bemboby Swales & Willis, Exeter, Devon, UK

CONTENTSList of ContributorsIntroductionAcknowledgments1 Laying the Foundation of Punishment Against Black MalesLiza Chowdhury and Rashanna Butlerviixxii12 Black Males and their Experiences with Policing Under the“Iconic Ghetto” in Ferguson, MissouriJason M. Williams113 From Savages to Super-Predators: Race, Lynching, and thePersistence of Colonial ViolenceDarryl Barthé214 Perceptions of Black Male Disproportionality in theCriminal Justice SystemRay V. Robertson and Cassandra Chaney335 Black Males and CourtsCrystal S. Collier496 Prison Health and Black MalesLaTrelle D. Jackson and Danielle Graddick597 Black Male Mental Health and PrisonChristopher St. Vil73

viContents8 Failures of Reintegration and the Return to PrisonSean Wilson859 Racial Politics and Policies of ReentryCalvinJohn Smiley9510 Institutionalized Mental Trauma and Generational TransmissionSteven KniffleyIndex109121

CONTRIBUTORSLiza Chowdhury, PhD, is an activist scholar and co-founder of the non-profit organizationReimagining Justice. The organization advocates for creating healing-centered justiceresponses, justice reinvestment in communities to create safe havens for youth, educationalsupport for the socio-emotional needs of children, and culturally appropriate mental healthprograms. She has over a decade of experience working in the field of community corrections.Presently, she teaches criminal justice courses as an Assistant Professor at Borough of Manhattan Community College (City University of New York) in the Department of Social Science,Human Services, and Criminal Justice.Rashanna Butler, BA, is a native of Atlantic City, New Jersey. She attended FairleighDickinson University, Metropolitan Campus, where she graduated with double honors.Rashanna now attends Washington and Lee University School of Law and is currently inher second year. Rashanna hopes to become a criminal defense attorney after law school andserve underrepresented communities.Darryl Barthé, PhD, is an historian of race, Americanization, and colonial violence, withan abiding interest in historical criminology. Currently residing in Brooklyn, New York,he has held teaching positions in the Department of History at the University of NewOrleans, and in the Department of American Studies at the University of Sussex in Brighton (UK), as well as the University of Amsterdam and the University of Leiden, in theNetherlands.Ray V. Robertson, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Sociology in the Department ofSociology and Criminal Justice at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University in Tallahassee, Florida. He has written and published scholarly works in the areas of critical racetheory, police brutality, birthing options for African American women, boxing, the BlackSeminoles, African American college students, and Latina/o college students. He is presently working on a book tentatively titled Police Use of Excessive Force against African Americans: Understanding its Origins and Why it Persists with co-author Dr. Cassandra Chaney(Louisiana State University), forthcoming. In his spare time, he enjoys reading, exercising,and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

viiiContributorsCassandra Chaney, PhD, is a Professor in Child and Family Studies at Louisiana StateUniversity (LSU). Professor Chaney is broadly interested in the dynamics of AfricanAmerican family life, yet under this umbrella she examines the narratives of African Americans in dating, cohabiting, and married relationships, with a particular interest in: relationship formation, maintenance, and stability; how religiosity and spirituality support AfricanAmericans; and representation of African American couples and families (e.g., structuraland functional dynamics) in popular forms of mass media (i.e., television shows, movies,music videos, and song lyrics). In addition, Professor Chaney examines the unique sociohistorical challenges for Black families and her scholarship roots in a strengths-based perspective, and emphasizes the various ways that Black families remain resilient in the face ofmultiple challenges.Crystal S. Collier received her PsyD in Clinical Psychology at Wright State UniversitySchool of Professional Psychology in Dayton, Ohio. She is currently the Program Dean atthe Florida School of Professional Psychology (FSPP) at Argosy University, Tampa. Shehas expertise and teaches in the areas of diversity, family, and child therapy. Her theoreticalorientation is primarily influenced by assimilative psychodynamics and family systems. Priorto teaching at Argosy University, Tampa, Dr. Collier taught at Wright State University.She has examined the doctoral-level experiences of African American females in clinicalpsychology, diversity training, and the prevention of conduct disorders in preschool populations. She is interested in working with diverse populations of children, adolescents, families, and parents. She is professionally affiliated with the Association of Black Psychologists(ABPsi), the National Council of Schools and Programs in Professional Psychology(NSCPP), and the American Psychological Association (APA). Within the profession, sheconducts workshops and seminars locally and nationally on a broad range of topics associated with her interests.LaTrelle D. Jackson, PhD, ABPP, is a Professor at Wright State University in the School ofProfessional Psychology. Her areas of interest include community engagement/asset-basedassessment, youth advocacy, diversity issues, consultation, supervision, parent empowerment,group therapy, geriatric psychology, program development, career evaluation/planning, forensic psychology, student affairs/development, and higher education administration.Danielle Graddick, MA, PsyM, is a fourth-year doctoral student at Wright State Universityin the School of Professional Psychology. She received a Master’s in forensic psychology fromGeorge Washington University and plans to pursue a career as a forensic evaluator.Christopher St. Vil, MSW, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the University at Buffalo Schoolof Social Work. Prior to his appointment at the University at Buffalo, Dr. St. Vil held a postdoctoral fellow position in the Department of African American Studies at the University ofMaryland, College Park. His current research focuses on trauma and the experiences of victimsof violent injury. Currently he is evaluating the effectiveness of a Violence InterventionProgram in reducing rates of violent trauma recidivism in Metropolitan Washington, DC, andis the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson New Connections grant to conduct a systematicreview on hospital-based trauma recidivism. Dr. St. Vil received his PhD from the HowardUniversity School of Social Work and his Master of Social Work (MSW) from the StateUniversity of New York at Stony Brook, and is a former Graduate Education Diversity fellowof the American Evaluation Association.

ContributorsixSean Wilson, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at WilliamPaterson University. He earned his BS and MS in criminal justice at New Jersey City University and his PhD in the Administration of Justice at Texas Southern University. His researchinterests are radical criminology, prisoner reentry, critical policing, penology, race, class,gender and crime, community justice, social justice, and ethnographic methodologies. He isvery active in progressive circles and has presented at several academic conferences throughoutthe US.CalvinJohn Smiley, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Sociology Department of HunterCollege, CUNY. Smiley’s research focuses on issues of race, class, gender, urban inequality,and justice. He has been published in scholarly journals such as The Prison Journal, Punishment& Society, and Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. More about Smiley’s academic research, scholarship, and academic interests can be found at: www.cjsmiley.com.

INTRODUCTIONThe time has come for there to be an attempt at intersectionalizing Black males and justicewithin academic literature that examines crime and justice. This edited volume builds on previously published works (e.g., Butler, 2017; Davis 2017; Lemelle, 1997). This book exploresthe extent to which mainstream critiques in criminology and related fields are severely limitedin understanding the intersectional realities of Black males and their relationship with thecriminal justice system, and the consequential impact this contact has had on their respectivefamilies and communities. Relying on a multidisciplinary frame of inquiry, and critical perspectives, this volume methodically reviews the relevance of contemporary practices of criminaljustice processes and policies.The chapters in this volume are epistemically grounded in Black maleness—which is to saythey are written from the vantage point of the Black male experience. Great attention waspaid to capturing the human expression and experience of Black males as they matriculatethrough some of the key stages of the criminal justice system, but also once they are out of thesystem. Some chapters are empirical while others provide academic synthetization of scholarlyknowledge. In this current era of major social upheaval and the advent of Black Lives Matterand other social advocacy groups, foremost attention is being paid to intersectional analyses ofoppressed people under apparatuses of state violence and repression. For instance, the incomparable Kimberle Crenshaw, in response to a lack of attention to Black women and girls indialogues around state violence intervened with the #SayHerName hashtag. Crenshaw, onceagain, was reminding commentators of the importance of intersectional analyses that foreground the lived experiences of individual groups (or categories) as opposed to the one-sizefits-all approaches typically adopted in examinations around state violence and the broaderBlack community. This volume, however, looks at Black males, in particular because, althoughmuch attention is paid to this group, in-depth analyses have yet to be brought to the forefrontregarding their experiences and matriculation through the criminal justice system.This volume breaks from traditional commentaries because it is epistemically grounded inBlack maleness as a social location of immense oppression, repression, and violence. RusselBrown (1998) developed the concept, “criminalblackman,” in which she highlighted thatBlack men are conceptualized as inherent criminals. She ties the criminalblackman concept toslavery in its immediate aftermath when allegations of rape against white women were used asa means of violent and often deadly forms of social control over Black male bodies. She

Introductionxiposited that this depiction of Black men as perpetual criminals has ascended to contemporarysociety with immeasurable consequences. This stereotype of Black men as criminals has discursively contributed to their mass incarceration and the disproportionate share of police brutalityagainst Black males.Russel-Brown’s concept of the criminalblackman is similarly situated alongside Skolnick’s(2011) term “the symbolic assailant.” He describes the symbolic assailant as a figment of a policeofficer’s imagination, a concoction of criminality manifested from hours of patrolling neighborhoods with the goal of needing to justify their existence as crime-fighters. Thus, the symbolicassailant is a psychological byproduct of chronic suspiciousness that officers learn to practice whileon the job. When one conjoins the criminalblackman with the symbolic assailant s/he is paintingthe socio-racial historical and contemporary experience of Black males in American society. Blackmales often must navigate through those two prisms of extreme suspicion, a reality that JonesBrown (2007) has argued makes them forever the symbolic assailant. Because of the legacy of slavery and the contemporary baggage of racism, Black males find themselves unable to emancipatethemselves from the suspicion of inherent criminality imposed upon them during slavery.This volume attempts to unpack the above concepts by looking at how Black men experiencethe criminal justice system and the collateral consequences these experiences have on their familiesand communities. Chowdhury and Butler provide a concise but comprehensive review of punishment practices against Black males. They foreground the chapter in the legacy of slavery whileworking through the civil rights era and to contemporary society. Williams presents a qualitativeexamination of narratives collected in Ferguson, Missouri, around Black male experiences with thepolice and uses Elijah Anderson’s concept the “Iconic Ghetto” and Cruse’s idea of “Internal Colonialism” to make sense of participants’ accounts. Barthé provides a quintessentially historical assessment of persisting colonial violence against Black bodies and its particular impact on Black males.He moves from the colonial era up through contemporary instances of such violence, paying closeattention to the collusion between the state and culture. Robertson and Chaney empirically examine perceptions of Black male disproportionality in the criminal justice system on the internet. Collier takes aim at the courts and uncovers the subtextual violence that Black males often face in trialproceedings. She carefully covers the role of judges, prosecutors, and juries in the suffering ofBlack males at the hands of American courts. Jackson and Graddick delve into prison health discourses and their effects on Black males. St. Vil challenges readers to consider the mental healthimplications behind mass incarceration and its deleterious effects on Black males. Wilson takes aimby empirically assessing some of the trying issues around Black males and reintegration; whereasSmiley provides an in-depth analysis of racial politics and policies of reentry. Kniffley closes thebook with a chapter on how punishment rendered to Black males constitutes an institutionalizedmental trauma that is passed down through generational transmission.ReferencesButler, P. (2017). Chokehold: Policing Black Men. New York: New Press.Davis, A. J. (2017). Policing the Black Man: Arrest, Prosecution, and Imprisonment. New York: Pantheon Books.Jones-Brown, D. (2007). Forever the Symbolic Assailant: The More Things Change, The More TheyRemain the Same. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(1), 103–122.Lemelle, A. J. (1997). Black Male Deviance. Westport, CT: Praeger.Russell, K. K. (1998). The Color of Crime: Racial Hoaxes, White Fear, Black Protectionism, Police Harassment,and Other Macroaggressions. New York: NYU Press.Skolnick, J. (2011). Justice without Trial: Law Enforcement in Democratic Society (4th edition). New Orleans:Quid Pro.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSWe would like to give thanks to the Consortium on Race, Gender and Ethnicity (CRGE) atthe University of Maryland, College Park that brought us together via the Intersectional Qualitative Research Methods Institute (IQRMI) back in 2015. We give thanks to the faculty andstaff affiliated with CRGE for their hard work and we hope that the consortium’s work maycontinue well into the future such that other underrepresented minority scholars may takeadvantage of its content and opportunities. Our collective effort in this project is the sum oftools learned at IQRMI.We also give thanks to our family and friends who supported us throughout this process.We would be remiss not to thank our contributors, without their efforts the book would notbe complete.

1LAYING THE FOUNDATION OFPUNISHMENT AGAINST BLACK MALESLiza Chowdhury and Rashanna ButlerIntroductionIn 2016, the case of Brock Turner made headlines around the country because it furthered theargument about the disparity of punishment that continues to over incarcerate and disenfranchiseblack men. Brock Turner, a white male, was convicted of three counts of sexual assault and, despite compelling evidence and a heartfelt letter from the victim, sentencing Judge Aaron Perskydecided to administer a lenient sentence. According to the Atlantic, in Judge Persky’s dissent, hementioned that a prison sentence would have “a severe impact” and “adverse collateral consequences” on Turner. Judge Persky accurately acknowledged the consequences of incarceration andthe difficulties a person faces once they fall within the web of the criminal justice system. However,historically, this country has not afforded black men the same form of empathy.Black men continue to be overrepresented in the prison system (Kilgore, 2015). The punitivenature of the criminal justice system has had an extremely negative impact on the economic andpolitical growth of African American men since the abolition of slavery. The collateral damage ofmass incarceration often found in the lives of African American men has included loss of votingpower, lack of economic stability, and estrangement from their families. In addition, individualdamage involves a depreciation of earning potential (Roberts, 2004), health issues (Morehart,2014), homelessness (Smith & Hattery, 2010)b being stamped with stigmatizing labels (Besemer,Farrington, & Bijleveld, 2017). Black men have suffered the demoralization and extreme punishment inflicted by the never-ending surveillance of the criminal justice system. At every stage of thecriminal justice system, they are more likely to face different outcomes from those of their Whitemale counterparts. This chapter will highlight the history of punishment towards black men thathas led to our current mass incarceration system. It will also explain disparate punishment outcomesblack men face at various stages of the criminal justice system.The Foundation of Mass Incarceration: The Racist Legacy of SlaveryThe carceral state of African American men is deeply rooted in American history. The UnitedStates has a racist legacy in the treatment of black men that has continued to punish themsince the beginning of this country (Wacquant, 2001). Even the writers of the constitutionwere slave owners. While they were writing about the importance of equality and freedom

She received a Master's in forensic psychology from George Washington University and plans to pursue a career as a forensic evaluator. Christopher St. Vil, MSW, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the University at Buffalo School of Social Work. Prior to his appointment at the University at Buffalo, Dr. St. Vil held a post-