Transcription

0101010101a memoir0101A0101010101

For Karen, Michael, and Christopher

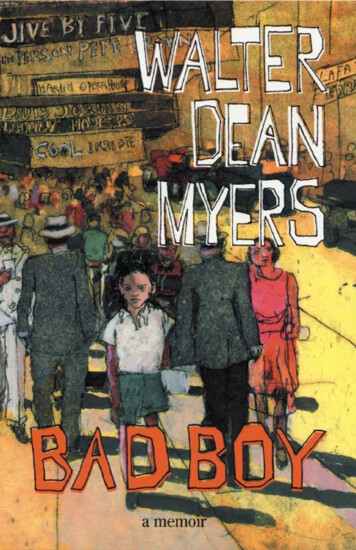

ContentsRootsHarlemLet’s Hear It for the First Grade!Arithmetic SummerBad BoyMr. Irwin LasherI Am Not the Center of the UniverseA Writer Obser vesSonnets from the PortugueseHeady Days at Stuyvesant HighThe Garment CenterGod and Dylan ThomasMarks on PaperThe StrangerDr. HolidayBeing Black1954Sweet SixteenThe TypistBooks I’ve TypedAbout the AuthorOther Books by Walter Dean MyersCreditsCoverCopyrightAbout the 88199207

RootsEach of us is born with a history already in place.There are physical aspects that make us brown-eyedor blue-eyed, that make us tall or not so tall, or giveus curly or straight hair. Our parents might be rich orpoor. We could be born in a crowded, bustling city orin a rural area. While we live our own individual lives,what has gone before us, our history, always has someeffect on us. In thinking about what influenced myown life, I began by considering the events andpeople who came before me. I learned about most ofthe people who had some effect on my life throughfamily stories, census records, old photographs, and,in the case of Lucas D. Dennis, the records of theWorks Progress Administration at the University ofWest Virginia. 1

The Works Progress Administration was a government program formed to create jobs during theDepression years. It did this by starting a number ofprojects, including state histories. Among the notes ofthe interviewers putting together a history of WestVirginia, I came across this entry.Life of a SlaveLucas D. Dennis was one of the one hundred and fiftyslaves that Steve Dandridge owned before the Civil War.This slave is ninety-four years old. He was born inJefferson County. His mind is very bright, he still has twoof his own teeth, his hair is gray and [he] wears a heavybeard which is also gray.After the Civil War he came to Harpers Ferry and builthimself a house, which is on one of the camping groundsused during the war. This house is on Filmore Ave. andthe corner of a lane leading to where many soldiers wereburied and later taken up and carried to their burialground in Winchester.He lives with his wife, she is eighty-four. He saw JohnBrown and remembers well the day he was hanged.Lucas D. Dennis was my great-great-uncle. Priorto the Civil War, when West Virginia was still part ofthe state of Virginia, these ancestors of mine wereslaves on a plantation called The Bower, in Leetown,Virginia. The 1870 census still listed Lucas D. Dennis 2

as living on the plantation, but I knew, from familystories, that he did indeed move to Harpers Ferry andthat part of the Dennis family moved to Martinsburg,West Virginia, less than ten miles from The Bower. Atthe time of the interview with Lucas D. Dennis, theDennis family in Martinsburg had merged with theGreen family. One of the women of the Green family,Mary Dolly Green, later became my mother.I have no memory of Mary Dolly Green. I knowthat she gave birth to me on a Thursday, the twelfth ofAugust, 1937. I have been told that she was tall, witha fair complexion. Mary had five children: Gertrude,Ethel, George, me, and Imogene. Shortly after the birthof my sister Imogene my mother died, leaving myfather, George Myers, with seven children, two of them,Geraldine and Viola, from a previous marriage. When Iimagine my mother, I think of an attractive youngwoman with the same wide smile as my sisters’. I wishI could have known her. However, today, when I thinkof “mother,” I think of another woman, my father’s firstwife, Florence Dean.Florence Dean’s mother emigrated from Germanyin the late 1800s. A cook by profession, Mary Gearhartsettled outside Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in NewFranklin, Pennsylvania. There she met and married aNative American by the name of Brown. The couple 3

had one daughter, Florence. Mary Gearhart, a small,pleasant woman, worked at a number of restaurantsbefore finding a job in a German hotel in Martinsburg,West Virginia.When Florence was old enough to work, she alsocame to Martinsburg. It was while working at thehotel that she met a young black man, George Myers.The two young people began to see each other sociallyand were married when Florence was seventeen.From this marriage came two children, Geraldine andViola. Unfortunately, the marriage ended in divorce,and Florence returned to Pennsylvania. The fact thatFlorence had married a black man did not sit well withher German relatives, and she was made to feel unwelcome. She decided to move to Baltimore, Maryland,where she met Herbert Dean.Herbert Dean lived in Baltimore with his father,stepmother, two sisters, Nancy and Hazel, and hisbrother, Leroy. His father, William Dean, was a tall,handsome, and opinionated man who had little use forformal education aside from reading the Bible, andeven less use for women. He ran a small hauling business in Baltimore that consisted of several wagons andteams of horses. He expected his sons to enter thebusiness when they were of age. When trucks beganto replace horses and wagons, he scoffed at the idea, 4

labeling the trucks as a mere fad that would never last.Even as his business declined, he stubbornly stuck tohis beliefs. By the time he was nine, Herbert Dean wasalready working, pulling a wagon through the streetsof the city, collecting scraps of wood, cutting it for kindling, and selling it door to door to light the fires in theold coal stoves that most people had at the time.Herbert had left school after the third grade, realizingthat he was needed to help support the family.By the time Herbert reached manhood, his father’shauling business was no more than a way of making afew dollars on occasion, and when William Dean stilldeclined to invest in trucks, both of the boys struck outon their own. Leroy decided to remain in the Baltimorearea, and Herbert decided to try his luck in New YorkCity. Herbert had met a woman who interested him.She had been married previously and had two children,but now she was single and still quite attractive. Thewoman, Florence, was white, and that posed a problemin Baltimore. Perhaps, Herbert thought, it would beless of a problem in New York.Herbert and Florence married and moved toHarlem. Herbert first found work with a moving company owned by the gangster Dutch Schultz. Eachmorning, men would line up on the street corners, andthe Schultz trucks would pick up as many men as they 5

needed that day. When Schultz was not hiring, therewere occasional jobs to be had at the docks, loading andunloading ships. Eventually, Herbert found a permanent job as a janitor with the United States RadiumCorporation in downtown New York.As a young couple Herbert and Florence made theHarlem party scene. When Herbert’s boyhood friendChick Webb came to New York, he introduced Herbertto some of his show-business pals such as Bill Robinsonand Fats Waller. Herbert even entertained the idea ofgetting into music and bought a slide trombone at apawnshop. Florence hated the trombone, disliked jazz,and wanted to be reunited with her daughters, whowere still living in Martinsburg with their father.Herbert agreed to bring Florence’s two daughters, Geraldine and Viola, to New York and drove downto Martinsburg in the black Ford he had bought. It wasduring this visit that he met George Myers, Florence’sfirst husband, her two daughters, and George’s children by Mary Myers.The girls were brought to Harlem, and severalmonths later it was decided that Herbert and Florencewould also take the youngest boy, Walter Milton Myers. 6

HarlemHarlem is the first place called “home” that I canremember. It was a magical place, alive with musicthat spilled onto the busy streets from tenement windows and full of colors and smells that filled my sensesand made my heart beat faster. The earliest memory Ihave is of a woman who picked me up on Sunday mornings to take me to Sunday school. She would have fiveto ten children with her when she rang our bell on126th Street, and we would go through the streetsholding hands and singing “Jesus Loves Me” on ourway to Abyssinian Baptist. I remember being comforted by the fact that Jesus, whom I didn’t even know,thought so much of me. After church we would bebrought home, again holding hands and singing ourway through the streets of Harlem. 7

What life was about for me in those early yearswas being with the woman I was learning to call Mama.When Florence Dean was home, I would follow herfrom room to room as she cleaned, talking about anything that came to mind, knowing that she wouldalways listen. Any house in which she lived was keptspotless. Mama had a time to sweep the floors and atime to mop them. There was a time to wash clothesand a time to iron them, fold them, and put them away.Each holiday meant taking all the dishes down fromthe shelves, even the ones we never used, and carefullywashing and drying them, as well as the windows ofthe dish cabinet.Mama didn’t work outside the house when I firstarrived in New York, but that changed from time totime. I remember that when I was four, a woman in thebuilding was taken on as my caretaker during the dayswhen Mama worked. Mama did what she called “day’swork,” meaning that she cleaned other people’s apartments and was paid by the day. The woman who tookcare of me gave that chore to her children, who delightedin torturing me by hiding in the closet and makingbelieve they were ghosts. I was a bawler, screaming infear at all the appropriate moments, which delightedthem. I learned how mindlessly cruel some childrencould be. 8

We were far away from credit cards in those days,and the equivalent was an account at the corner grocery. Mama, who was determined that I should neverbe hungry, arranged with the grocer to give me food ifI was hungry and to put it on her account. What I actually did when I had the chance was buy penny squaresof chocolate. Soon every kid on the block knew that Icould get “free” chocolates. One weekend both thegrocer and I got a good talking-to, and my account cameto a crashing end.What I loved most about Harlem, though, was themusic. There were radios everywhere, and little girlsjumped double Dutch to Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway,and Glenn Miller. My sisters, Gerry and Viola, dancedwith me in the house, but the girls in the street wouldn’tdance with me, so I danced by myself. I had taughtmyself a little dance that I called “the boogie.” Mydancing was amusing enough for people to throw pennies to me when I danced. When I had enough pennies,I would scoop them up and run to the grocer’s to buymy favorite colored icy pops. I could keep this up forhours and loved it until one day I had a stomachacheand went home crying. When Mama got home fromwork, she put me on the toilet and sat on the edge ofthe bathtub to comfort me. Within minutes I was beingsnatched up and rushed to Knickerbocker Hospital. 9

Mama had reasoned that the red liquid passingthrough my intestines had to be blood. At the hospitalthe doctors were equally alarmed until a few tests confirmed that I had consumed so many icy pops that thefood coloring was going straight through. It was clearI needed more supervision during the day, and Mamafound another baby-sitter, who took care of a numberof children.This woman had playground apparatus in herbackyard, which I liked a lot. I was told not to play onthe climbing bars, but I tried them anyway. Getting tothe top was easy enough and not nearly as excitingas falling off, headfirst, onto the cement below. I’vealways had a big head, and I must have looked a sightthat night, with bandages covering half my face, whenMama picked me up. She decided to stay home to takecare of me for a while.My two sisters were already in their teens and hadthe job of being young ladies. I was the baby of thefamily and the only boy and got most of the attention,which I enjoyed. I claimed Mama for my own and wasjealous of any attention she paid to her daughters.When Gerry received a fancy watch as a present, I wasannoyed. Gerry hadn’t changed, and so I thought it wasthe watch that made her special.“Can I have a nickel?” I asked Mama. A week had 10

passed since Gerry had received the watch, and Mama,her forehead dripping sweat, was doing the wash in atub of scalding water, pushing the sheets down into thehot liquid with a stick. Mama shook her head.“Can I have a nickel?” I asked again, wanting herto stop the washing and perhaps take me to the cornerstore for an icy pop.“Later, Walter,” she said. “I’m busy now. Go play.”“I’ll break Gerry’s watch,” I said.“Boy, go into the living room and play!” she said,sternly.The watch didn’t break right away. I hit it with myshoe, and nothing happened. Then I hit it with myfather’s shoe, and it still didn’t break. Then I hit it withboth shoes as hard as I could until I saw a crack in thecurved crystal. This I took proudly to Mama.A spanking is a spanking is a spanking. Mama wasstrong enough to hold me by the corner of my shirt atthe shoulder and lift me so that I could not get a firmfooting on the ground. Then, still sweating from herefforts at washing the sheets, she laced into me with afolded belt that, from that time on, became “the strap.”Of course, she could have prevented the watch frombeing broken if she had only believed me when I toldher that I was going to break it. Instead she coveredmy legs and hands with welts with the strap. When 11

Gerry came home from work, she wasn’t pleased,either.I needed discipline, but my adoptive father,Herbert Dean, hated to see me crying. So the nexttime Mama worked outside the house, I was sent to myaunt Nancy, my father’s sister, who lived in downtownNew York.Division Street on New York’s Lower East Sidewas as wonderful to me as Harlem. There were fewblack people in the area, but at my age, which wasprobably five, I was not really aware of racial differences. What was on Division Street was Aunt Nancy,her husband, who

Bad Boy 35 Mr. Irwin Lasher 48 I Am Not the Center of the Universe 65 A Writer Obser ves 78 Sonnets from the Portuguese 90 Heady Days at Stuyvesant High 101 The