Transcription

Mª José Gil Moreno, Marta Cerezo García, Raluca Marasescu, Ana Pinel González, Laudino López Álvarez and Yolanda Aladro BenitoPsicothema 2013, Vol. 25, No. 4, 452-460doi: 10.7334/psicothema2012.308ISSN 0214 - 9915 CODEN PSOTEGCopyright 2013 Psicothemawww.psicothema.comNeuropsychological syndromes in multiple sclerosisMª José Gil Moreno1, Marta Cerezo García2, Raluca Marasescu2, Ana Pinel González2, Laudino López Álvarez3 and Yolanda Aladro Benito21Hospital de Móstoles, 2 Hospital Universitario de Getafe and 3 Universidad de OviedoAbstractResumenBackground: Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis (MS) is common(45-65%).Deficits occur in speed of information processing (SIP), memory,attention, executive functions (EF) and visuoconstruction.Involvement ofcognitive functions like language and gnosis is rare and lesser known. Ouraim is to describe the cognitive function and the clinical and radiologicalfeatures of five patients with MS and with neuropsychological syndromes(NPS). Method: Retrospective review of MS patients with NPS studied,using specific tests of SIP, memory, attention, EF, visuo-spatial abilities,praxis and language. Results: The sample included four women (3relapsing-remitting MS/1 secondary progressive MS) and one man withprimary progressive MS (aged between 30-55 years). Cognitive symptomswere the initial complaint in three cases. Three cases presented apperceptiveagnosia and constructive apraxia, one case presented alexia with agraphiaand the fifth patient presented motor aphasia. Four patients sufferedcognitive dysfunction considered typical of MS. Magnetic resonanceimaging (MR) in all cases showed high lesion volumes in T1 and T2weighted sequences. A good correlation was observed between cognitivedeficits and the location of the lesions in four patients. Conclusions: NPSmay be the initial complaint in MS patients, often associated with othercognitive deficits, and it shows a close relationship with lesion location.Síndromes neuropsicológicos en la esclerosis múltiple. Antecedentes:entre el 45-65% de los pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM) manifiestandéficits cognitivos en velocidad de procesamiento de la información (VPI),atención, memoria, funciones ejecutivas (FE) y visuoconstrucción. Laalteración del lenguaje y la gnosis visual es infrecuente y poco reconocida.El objetivo es la descripción cognitiva, clínica y radiológica de cincopacientes con EM con síndromes neuropsicológicos (SNPS). Método:revisión retrospectiva de pacientes de EM con SNPS estudiados mediantetest específicos de atención, memoria, VPI, FE, visuoconstrucción, gnosisvisual y lenguaje. Resultados: la muestra incluyó cuatro mujeres (3 EMremitente recurrente, 1 EM secundaria progresiva) y un varón con EMprimaria progresiva (edades entre 30-55 años). Los déficits cognitivosfueron el síntoma inicial en 3 casos. Tres presentan agnosia aperceptivay apraxia constructiva, uno alexia con agrafia y el quinto afasia motora.Cuatro asocian disfunción cognitiva “típica” de EM. En resonanciamagnética observamos alto volumen lesional en secuencias potenciadasen T1 y T2 y correlación entre los déficits cognitivos y la localización delas lesiones en 4 de ellos. Conclusiones: los SNPS pueden ser la quejainicial en la EM, con frecuencia se asocian a otros déficits cognitivos ymanifiestan una estrecha relación con la localización de la lesión.Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, neuropsychological syndrome, cognitiveimpairment, visual gnosis, aphasia.Palabras clave: síndrome neuropsicológico, alteración cognitiva, gnosisvisual, afasia, esclerosis múltiple.Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of theCentral Nervous System (CNS) characterized by inflammation,demyelination and axonal degeneration (Kornek & Lassmann2004). It is the second cause of disability in young adults (Nieto,Sánchez, Barroso, Olivares, & Hernández, 2008). Typically, MSleads to disability because of cumulative motor, sensory andor visual deficit. Between 45 and 65% of the patients developvariable cognitive dysfunction over the course of the disease,being generally more frequent and severe in late phases (6 - 10%)and coexisting with physical impairment (Halligan, Reznikoff,Friedman, & La Rocca, 1988). However, cognitive dysfunctioncan be a major complaint and the main cause of disability in theinitial stages and, in contrast to motor or sensory deficits, it doesnot tend to improve (Calabrese et al., 2009; Staff, Lucchinetti, &Keegan, 2009). When cognitive deterioration in MS becomes thepredominant symptom, it has been named ‘Cortical MS’ by someauthors (Zarei, Chandran, Compston, & Hodges, 2003).Although in MS there is no specific pattern of cognitivedysfunction, the functions most commonly impaired are speedof information processing (SIP), attention, memory, executivefunctions (EF) and visuospatial and visuoconstructive abilities(Arango-Lasprilla, DeLuca, & Chiaravalloti, 2007; Genova,Sumowski, Chiaravalloti, Voelbel, & DeLuca, 2009; Patti, 2009).The brief batteries designed for the routine study of cognitivedysfunction in MS basically include the assessment of thesefunctions (Boringa et al., 2001; Duque et al., 2012). The presence ofneuropsychological syndromes (NPS) (cognitive and behaviouraldisorders observed in cerebral disease with involvement of corticalareas: agnosia, aphasia, apraxia) has only been described inisolated cases of MS, largely without regulated neuropsychologicalevaluation. Anecdotal cases have been published referring to acuteaphasia (Devere, Trotter, & Cross, 2000), alexia with agraphia(Day, Fisher, & Mastaglia, 1987), alexia without agraphia (Dogulu,Received: November 9, 2012 Accepted: June 27, 2013Corresponding author: Yolanda Aladro BenitoServicio de NeurologíaHospital Universitario de Getafe28905 Getafe (Spain)e-mail: yaladro.hugf@salud.madrid.org452

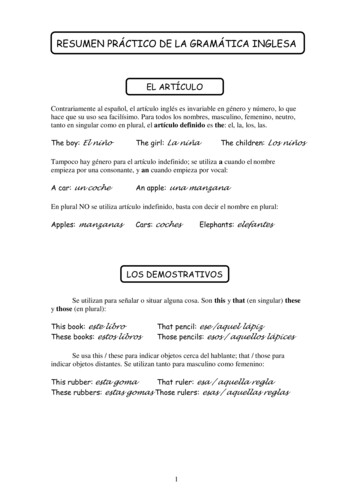

Neuropsychological syndromes in multiple sclerosisKansu, & Karabudak, 1996; Mao-Draayer & Panitch, 2004), visualagnosia (Okuda et al., 1996) and patients with more than one severecognitive symptom, with criteria for dementia (Staff et al., 2009;Stoquart-ElSankari, Périn, Lehmann, Gondry-Jouet, & Godefroy,2010). When cognitive impairment is the initial and predominantsymptom, it constitutes a diagnostic challenge (Calabrese, Filippi,& Gallo, 2010; Rinaldi, Calabrese, & Grossi, 2010).The objective of this study is the cognitive assessment andthe clinical and radiological description of five patients with MSpresenting with NPS, evaluated by means of specific cognitivetests.MethodParticipants and procedureThis study was conducted in the Multiple Sclerosis Unit, at theGetafe University Hospital. From a total of 164 patients with MS(McDonald 2005 diagnostic criteria) (Polman et al., 2005) andneuropsychological evaluation, five were selected for presentingneuropsychological symptoms involving changes in cognitiveprocesses such as language and visual gnosis.An analysis of demographic data, course of the disease anddegree of physical disability (Kurztke disability status scale,EDSS) (Kurtzke, 1983) was carried out at the moment of diagnosisof the NPS.An estimate of the lesion volume was made by Magneticresonance imaging (MR) axial T1- and T2-weighted sequencesand coronal fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR). A lowlesion volume (LV) was defined by the presence of 9 or fewer smallsize lesions ( 1 cm of larger diameter), a moderate LV by theexistence of more than 9 lesions, at least 2 being large (diameterbetween 1 and 2 cm) and high LV if there was at least one largeconfluent plaque (larger than 2 cm in diameter). Cerebral atrophywas qualitatively measured by inspection of the width of sulci andof the third and the lateral ventricles in relation to age. Finally,we performed a second neuropsychological evaluation in somepatients in order to estimate the progression or remission of thecognitive deficits.InstrumentsFrom October 2004 to March 2012, an extensive routineneuropsychological evaluation was performed including thefunctions typically impaired in MS (IPS, memory, learning,attention and EF), language and visuospatial abilities. The degreeof anxiety and depression was also measured with the BeckDepression Inventory (BDI) and Spielberger’s State-Trait AnxietyInventory (STAI). Values lower than the normative values of eachtest were considered pathological.Clinical casesA summary of the clinical and radiological characteristics, aswell as the results of the cognitive tests, is found in Tables 1-5.Case number 1 is a 33-year-old woman. In 2001, she had the firstMS symptom, consisting of motor impairment of the right hand.The second flare occurred in 2006 with motor-sensory impairment;therefore, the patient was diagnosed of relapsing-remitting MS(RRMS). Examination revealed signs of pyramidal, sensory andgait impairment (EDSS score: 3). The patient did not experiencesymptoms of cognitive deterioration at any time. However, aprotocol neuropsychological evaluation in 2007 found a normalintelligence and low to moderate changes in IPS, attention, EF andvisuoconstruction. Because difficulties at reading and writing wereobserved during the evaluation, additional linguistic processingwas examined using the PALPA battery (Spanish versionEPLA: Valle & Cuetos, 1995). The patient presented adequatephonological processing in the differentiation of sounds, lettersand words independently of the imageability, frequency of use ormorphology. She repeated sentences well and exhibited a good levelof picture naming. Significant difficulties were observed in readingand writing, and she showed significant effects of imageability,frequency of use and inflectional morphology. The patient also haddifficulties reading non-words, writing functional words and shecommitted errors depending on derivational morphology. Thesedifficulties resulted in mistakes in the orthographic input lexiconand in grapheme-phoneme conversion (see Table 1). Symptomsof fatigue, anxiety and depression were also present. Cranial MRshowed multiple large demyelinating lesions, some confluentin the deep white matter (WM) in both cerebral hemispheres,predominantly in the left parietal-occipital-temporal area, clearcortical atrophy and a thinning of the corpus callosum (Figure 1).At a new neuropsychological evaluation in 2009, a remission ofher alexia-agraphia syndrome was observed.Case number 2 is a 30-year-old woman with no relevant medicalhistory. She was admitted in 2008 with a subacute left hemispheresyndrome consisting of right hemiparesis and impossible verbalexpression. Neurological examination revealed a mild confusionalstate with a trend to agitation and a slightly decreased level ofconsciousness. The severity of the neurological involvement did notpermit an adequate neuropsychological examination but confirmedsevere motor aphasia with absence of spontaneous language andinability to repeat, name and produce automatic sequences. Thepatient was only able to utter two-syllable words and understoodbasic commands. Right unilateral visual and sensory neglect wasobserved together with severe right hemiparesis. MR showedan extensive lesion in the left frontal-parietal WM and twosmall lesions in the WM of the right hemisphere. No corticalinvolvement was observed (Figure 2). A brain MR after 4 monthsshowed conversion to MS by the appearance of two new lesions,one of them active in the left occipital region, and the patient wasdiagnosed of RRMS. In 2009, a neuropsychological examinationwas carried out in another centre. The reports from this evaluationpointed out to an impairment in linguistic processing in both writtenand oral expression, with a slight alteration in understanding,a mild impairment in processing speed, attention, executivefunction (planning and working memory), memory and verballearning, with preservation of visuospatial memory. In our centre,a neuropsychological evaluation performed in 2010 revealed anear-complete remission of the aphasia. Using the PALPA andthe Boston Naming Test (BNT) (Table 2), adequate performancewas observed in picture naming, phonological discrimination(words/non-words), lexical decision (depending on imageabilityand frequency) and linguistic understanding of sentence readingand repetition of words regardless of length, in both reading andwriting. Only mild alterations in the repetition of non-words (nonsignificant), SPI and attention were observed. In the BDI, thepatient showed a slight lowering in mood, and the scores in theSTAI were slightly elevated.453

Mª José Gil Moreno, Marta Cerezo García, Raluca Marasescu, Ana Pinel González, Laudino López Álvarez and Yolanda Aladro BenitoCase number 3 is a 43-year-old woman with secondaryprogressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) of 10 years of evolution andan EDSS score 5 by impairment of walking, associated with milddecrease of visual acuity ( 20/30) and fatigue. She complainedof spatial disorientation, often getting lost in places close to herhome. The first neuropsychological evaluation in April 2004 founddifficulties in the visual perception of objects and space, and inthe construction of figures under visual guidance. The patient hadproblems in integrating figures into a whole, in the mental rotationof figures and elements and also in using three-dimensionality.These deficits were explained by apperceptive visual agnosia,spatial agnosia and moderate constructional apraxia and were notTable 1CASE 1: Clinical details and cognitive resultsSexLevel of education (years of schooling)Age in the first neuropsychological evaluation (NPSE).EDSS in the first NPSE.Disease duration in the first NPSE (Years).Female113336MRI: T1 lesion volume T2 lesion volume Cerebral atrophyHighHighYesTESTSWAIS-III (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale)Digit Symbol-CodingBlock DesignSymbol SearchLetter-number sequencingWMS-III (Wechsler Memory Scale)Logical Memory IFamily Pictures ILogical Memory IIFamily Pictures IIRey Osterrieth Figure (ROCF)Type of the copyAccuracy of copyTime of copyImmediate recall conditionBNT (Boston Naming Test)Total ScoreCTMT (Comprehensive Trail Making Test)Tests 1/2/3/4/5IndexBADS (Behavioural Assess. of Disexecutive Syndrome)Temporal JudgementZoo MapWCST (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test)Total % of errors% Perseverative ResponsesNº of categories completedTrials to complete 1st categoryFailure to maintain setLearning to LearnPALPA (Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language)ReadingLetter discrimination W/NWVisual lexical decision HIHF/HILF/LIHF/ LILFVisual lexical decision. flex./deriv./non-word.Reading HIHF/HILF/LIHF/ LILFReading regular/Irregular.Non words reading 5 letters/6 lettersReading sentencesWritingWriting length 5 letters/6 lettersWriting to dictation HIHF/HILF/LIHF/ LILFWriting to dictation Noun/Adjective/Verb/functionWriting imageability. Nouns/functional WWriting to dictation Regular/ Derived/ IrregularWriting non-words 5 letters/6 letters454SCORES2007SCORES2009NormativevaluesMax Score7457Max Score10131112Percentile75607570Raw Score58Standard. S28/29/24/19/2723Profile22Percentile9094 16 16 16 16Max Score6869Max Score13161319Percentile75805030Raw Score57Standard. S26/34/37/30/2929Profile24Percentile8692 16 16 16 16Max Score10101010Max Score10101010Percentile50505050Raw Score54Standard. S5050Profile22Percentile5050 16 16 16 16Z .23/-3.27/0.580.35/0.1-1.38/-0.62-1.91Z 4-1.78/-3.71-3.4/-3.9/-1.680.27/-1.72Z 3/0.580.35/0.1-0.33/-0.330Z 5-0.35/00/0.23/-0.360.27/-0.95Z score0000000Z score000000

Neuropsychological syndromes in multiple sclerosisjustified by the degree of visual impairment (see Table 3). Thepatient also showed alterations in other cognitive functions: IPS,attention, EF and verbal and visual episodic memory. The cranialMR showed confluent periventricular demyelinating lesions, andother multiple non-confluent lesions in frontal and parietal andoccipital areas, corpus callosum and also infratentorial, as wellas signs of significant axonal damage and subcortical and corticalatrophy. In a second neuropsychological evaluation in 2009,cognitive performance was similar, and no progression of visualagnosia was found. However, she showed a slight decrease in SPIand EF. On the other hand, the patient displayed a high level offatigue, symptoms of mild depression and mild anxiety.Table 2CASE 2: Clinical details and cognitive resultsSexLevel of Education (years of schooling)Age in neuropsychological evaluation (NPSE).EDSS in NPSE.Disease duration in the NPSE (years).Female123031.8MRI: T1 lesion volume T2 lesion volume Cerebral atrophyMediumHighNoTESTSWAIS-III (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale)Digit Symbol-CodingBlock designSymbol SearchLetter-Number sequencingWMS-III (Wechsler Memory Scale)Logical Memory IFamily Pictures ILogical Memory IIFamily Pictures IIRey Osterrieth Figure (ROCF)Type of the copyAccuracy of copyTime of copyImmediate recall conditionBNT (Boston Naming Test)Total ScoreCTMT (Comprehensive Trail Making Test)Tests 1/2/3/4/5IndexBADS (Behavioural Assess. of DisexecutiveSyndrome)Temporal JudgementZoo MapWCST (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test)Total % of errors% Perseverative ResponsesNº of categories completedTrials to complete 1st categoryFailure to maintain setLearning to LearnPALPA (Psycholinguistic Assessment ofLanguage processing in Aphasia)Discrimination minimal pairs words Equal/Different Auditory lexical decision HIHF/HILF/LIHF/ LILFRepetition: Length 3L/4L/5L/6LRepetition: non-words 3L/4L/5L/6LSCORE2010NormativeValuesMax Score51078Max Score2918Percentile75905050Raw Score55Standard S33/29/29/29/3829ProfileMax Score10101010Max Score10101010Percentile50505050Raw Score54Standard S5050Profile12Percentile7992 16 16 16 16Z score22Percentile5050 16 16 16 16Z .27/4.33/0.31/0.530000Case number 4 is a 44-year-old woman with a very active formof RRMS, both clinical and radiological. She suffered her firstepisode of the disease in 2006, with visual problems that impededher from moving into familiar places. In the following months, sheexperienced several relapses with sensory impairment and unstablegait. At a new neurological evaluation performed a year and a halflater, cognitive impairment was observed together with pyramidalsigns and mild cerebellar involvement, with an EDSS score of3.5 (excluding cognitive impairment). In the neuropsychologicalevaluation, severe cognitive deficits were found: apperceptivevisual agnosia, spatial agnosia, constructional apraxia, ideomotorapraxia and a significant alteration in coding and recovery of verbalepisodic memory. She also exhibited dysfunctions in EF and naming(Table 4). A behavioural disorder was also observed, includinginfantilism and emotional liability. A mood disorder with markedsymptoms of depression and anxiety was also present. The cranialMR showed multiple demyelinating lesions at periventricularand yuxtacortical level, with a relative predominance in theparietooccipital areas, and also an important number of lesions inthe brain stem. There were an elevated number of black holes andseveral of the occipital lesions showed gadolinium enhancing. Thepatient was treated with different immunomodulating drugs fromthe beginning, but her cognitive dysfunction progressed incessantlyto fully developed dementia. In 2011, after 5 years, the patient wasin a state of absolute dependence, needing 24-hour care.Case number 5 is a 57-year-old male patient with a historyof hypertension and high levels of cholesterol. His relativesrequested medical attention after observing progressive cognitivedeterioration in the last 2 years, which impeded him fromperforming the required tasks at work. The patient, a waiter byprofession, forgot the customers’ orders, confused spaces at homeand at work, had expression difficulties and was notably indifferentabout his mistakes. The neurological exam showed only cognitiveimpairment (EDSS score 0, without considering cognitiveimpairment). The neuropsychological evaluation confirmed visualimpairment in the perception of shape and space (apperceptivevisual agnosia) and in colour naming (colour anomie), whilemaintaining perception of colour, topographical spatialdisorientation, visuoconstructional impairment, preserving gestaltand simplification and ideomotor praxis for transitive gestures.The patient maintained verbal comprehension and the repetition ofwords but failed in the repetition of non-words. When dealing withspontaneous oral and verbal expression, there was a notable loss innaming abilities, construction of simple, grammatically incorrectsentences and hesitation. A decrease in the use of functional wordsand the presence of phonological and semantic paraphasia werealso observed. Reading was considered adequate albeit slow andwith some difficulty depending on the length of the sentenceand presence of non-words. Verbal expression was the mostaffected, with difficulties with substitution, addition and omission,especially in longer and less frequent words. Spontaneous writingwas characterized by grammatically incorrect sentences and adecrease in the use of functional words. These deficits resultedin difficulties in the phonological output lexicon, in acousticphonological conversion and in phoneme-grapheme conversion.Finally, the patient showed a low to moderate decrease in verbalepisodic memory (coding), IPS, attention and EF (Table 5) aswell as marked apathy. In another neuropsychological evaluationcarried out 8 months later, mild progression of language disorder(anomie), semantic memory and free verbal long-term memory455

Mª José Gil Moreno, Marta Cerezo García, Raluca Marasescu, Ana Pinel González, Laudino López Álvarez and Yolanda Aladro Benitowere all found. In the case history file collected from the family, thegreat effect of these difficulties on this patient’s daily life activitiescould clearly be seen. The MR showed multiple lesions in theperiventricular WM of both hemispheres and confluent plaquesin the parietal-temporal-occipital areas (Figures 3b and c). Twocerebrospinal fluid samples examined in two different laboratoriesshowed intrathecal IgG synthesis. Another MR performed one yearlater showed a new large left parietal yuxtacortical lesion.DiscussionThe patients we have described herein represent a particularclinical form of MS characterized by impairment in cognitivefunctions rarely affected in this disease, such as aphasia, alexia,agraphia and visual agnosia. Even though these cognitive processesare generally disturbed in cortical lesions, different pathologicalprocesses of the subcortical white matter can cause similar clinicalsyndromes (Damasio, 1992; Naeser et al., 1982).Table 3CASE 3: Clinical details and cognitive resultsSexLevel of education (years of schooling)Age in the first neuropsychological evaluation (NPSE).EDSS in the first NPSE.Disease duration in the first NPSE (years).Female843510MRI: T1 lesion volume T2 lesion volume Cerebral AtrophyModerateHighYesTESTSWAIS-III (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale)Digit Symbol-CodingBlock designDigit SpanSymbol searchLetter-Number sequencingWMS-III (Wechsler Memory Scale)Logical Memory IFamily Pictures ILogical Memory IIFamily Pictures IISpatial SpanRey Osterrieth Figure (ROCF)Type of the copyAccuracy of copyTime of copyImmediate recall conditionBNT (Boston Naming Test)Total scoreCTMT (Comprehensive Trail Making Test)Tests 1/2/3/4/5IndexBADS (Behavioural Assess. of Disexecutive Syndrome)Temporal JudgementZoo MapVerbal FluencyPhonemic Fluency (FAS)Semantic Fluency (animals, fruit, supermarket)WCST (Wisconsin Card Sorting Test)% total errors% Perseverative ResponsesNº of categories completedFailure to maintain setLearning to LearnVOSP (Visual Object and Space Perception Battery)Screening TestIncomplete LettersSilhouettesObject decisionProgressive SilhouettesDot countingPosition DiscriminationNumber locationCube ed Score258510Scaled Score76575Percentile5011010Raw Score50Standard S18/18/18/18/1818Profile31Raw - Average612Percentile576 16 16Raw Score201612141462064Scaled Score25748Scaled Score76575Percentile501251Raw Score52Standard S18/18/18/18/1818Profile31Raw - Average612Percentile3126Raw Score191117101311376Scaled Score1010101010Scaled Score1010101010Percentile50505050Raw Score54Standard S5050Profile22Raw - Average12-1317-18Percentile5050 16 16 16Cut-off Score151716151481876

Neuropsychological syndromes in multiple sclerosisOur first reported patient developed mild alexia withphonological agraphia in the context of a disease relapse,coincident with lesions in the left parietal and occipital areas,all evolving to complete remission at a later date. This deficitpresented only a very mild repercussion in her daily life and socialand occupational activities. In the second case, motor aphasiadue to a large lesion in the WM of the left hemisphere was thefirst sign of disease, and it was not associated with any change inother cognitive functions and it also subsequently remitted. In thispatient, the neuropsychological exam showed a large discrepancybetween verbal and visual performance, not in accordance withspontaneous expression observed in normal conversation. Thisincongruence and the slight reduction in performance on SPIand attentive tasks can be explained by the elevated degree ofanticipatory anxiety observed during the evaluation, as otherauthors have already observed (Nieto et al., 2008; Schulz, Kopp,Kunkel, & Faiss, 2006). The neuropsychological exam of thelast three patients showed apperceptive agnosia and constructiveapraxia in correspondence with bilateral lesions in the parietal andoccipital areas. The last patient also showed alterations in linguisticprocessing. All but one of the cases (Case 2) exhibited cognitiveimpairment typical of MS, with some deficit in the encoding ofverbal memory, SPI, attention and EF, similar to those describedTable 4CASE 4: Clinical details and cognitive resultsSexLevel of education (years of schooling)Age in neuropsychological evaluation (NPSE).EDSS in NPSEDisease duration in NPSE (years).Female8443.51.5MRI: T1 lesion volume T2 lesion volume Cerebral atrophyHighHighYesTESTSWAIS-III (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale)Picture completionVocabularySimilaritiesBlock DesignDigit SpanWMS-III (Wechsler Memory Scale)Logical Memory ILogical Memory IIMental controlInformation and OrientationVerbal fluencyPhonemic fluency (FAS)Semantic fluency (animals, fruit, supermarket)VOSP (Visual Object and Space PerceptionBattery)Screening TestIncomplete LettersSilhouettesObject decisionProgressive SilhouettesDot countingPosition DiscriminationNumber locationCube analysisScore2008NormativevaluesScaled Score19615Scaled Score313Percentile 1Raw -Average1014Raw ScoreScaled Score1010101010Scaled Score101010Percentile 50Raw -Average12-1317-18Cut-off Score180252041101151716151481876by other authors (Day et al., 1987; Devere et al., 2000; Okuda etal., 1996). We would like to highlight in three of our cases the goodcorrelation encountered between apperceptive visual agnosia andthe lesions observed in the parietal and occipital WM areas. Alsoremarkable is the recovery of language alterations observed in twoof the patients.NPS may be the initial form of presentation of MS (cases 2,4 and 5) (Devere et al., 2000; Dogulu et al., 1996; Mao-Draayer& Panitch, 2004) or, more frequently, they may appear in thecourse of the disease in association with physical disabilityinvolving other functional systems (Cases 1 and 3) (Day etal., 1987; Okuda et al., 1996). When they constitute the onlysymptom and occur progressively, as in our Case no 5, it can bedifficult to establish a diagnosis of MS (Stoquart-ElSankari etal., 2010); in this setting, the presence of intrathecal synthesis ofimmunoglobulins may be of great help. A rapid progression ofcognitive dysfunction along with severe functional deteriorationand dementia over a short lapse of time has been described insome other sporadic cases, similar to our Patient 4 (Staff etal., 2009; Stoquart-ElSankar et al., 2010). Some patients withcognitive impairment also display changes in the emotionalsphere, mostly euphoria, emotional instability, apathy and/orsymptoms of depression, also observed in our patients (Zarei etal., 2003; Zarei, 2006).The prevalence of NPS in MS is unknown. Possibleexplanations are the lack of studies focused on these specificcognitive deficits, and the fact that routine tests used in clinicalpractice only contemplate patterns of cognitive impairment typicalof MS (Boringa et al., 2001; Duque et al., 2012). In addition, thetests may be administered by non-specialized personnel not skilledenough as to detect other possible deficits which could deservea more specific investigation. In spite of this, their prevalence ispresumably low, as these cognitive deficits demand specializedcare because of the serious functional disability that they usuallygenerate. In fact, the presence of aphasia only represented 0.8%of the 2700 MS patients tested by Larner and Lecky (2007). Inspite of this probably low prevalence, it is important to considercognitive deterioration as a main symptom of MS, even in caseswhere other neurological disorders are minor, given their potentialrepercussion on socio-occupational activities.The substrate of cognitive impairment of MS, and in theseparticular NPS, is possibly brain atrophy. It may be that in theneuropsychological disorders involving typically cortical areas(aphasia, agnosia, apraxia), the grey matter (GM) atrophy is morerelevant than WM atrophy. For decades, we have known thataround 20% of the lesions in MS are found in the GM (Brownell& Hughes, 1962), and its clinical relevance and its importantcontribution to cognitive symptomatology are well recognized.Three types of lesions are found in the cerebral cortex, namelycortical-s

Friedman, & La Rocca, 1988). However, cognitive dysfunction can be a major complaint and the main cause of disability in the initial stages and, in contrast to motor or sensory defi cits, it does not tend to improve (Calabrese et al., 2009; Staff, Lucchinetti, & Keegan, 2009). When cognitive deterioration in MS becomes the