Transcription

REVISITING THE UNCANNY1Revisiting the Uncanny: a Model ofVisuality for Architectural SpeculationIs Vidler’s Uncanny Uncanny Enough?The Architectural Uncanny, Essays in theModern Unhomely by Anthony Vidler is asatisfying and provocative work.1 Erudite,thorough, and grounded in the intellectual andurban history of modern Europe, it has theadditional benefit of connecting a �s most curious terms. There is,in short, little in Vidler’s characteristicallywitty work that one could cite as ashortcoming on any level. This brief essaynonetheless asks, of some imaginary fan-clubof the uncanny, what might have happenedhad Vidler shifted his point of view slightly; ifhe had, as a matter of fact, applied theprinciple of the uncanny to his own inquiry?2This project begins with the beginning,Sigmund Freud’s original essay.3 This workhas been made widely available throughtranslation and re-printed as a stand-alonebook. Freud begins with an etymologicalconsideration of the words heimlich andunheimlich. Curiously, the word heimlich isitself “uncanny,” for it contains within its ownphilological past the seeds of the idea of theuncanny.The steps from the homely to the uncannyhave to do with hiding things. In the sensethat “hidden away” can be a part of coziness,it at first belongs to the security that can beoffered by the home: concealment from theeyes of strangers. Later, however, theuncanny comes to specialize on this theme,emphasizing “something that ought to haveremained a secret” but is discovered;something that was “there all the time” butonce brought to light becomes harmful or, atthe least, scary.Vidler’s study depends on examples of thearchitectural uncanny: being buried alive,homesickness,cyborgs,transparency.Adeptly, Vidler de-familiarizes the familiar.More time spent with Freud might have addedan element of structural interest by permittingthe uncanny to expand in several unexpectedways. What if, for example, Vidler had firstexplicated the famous example of the contestbetween Zeuxis and Parhassius, the Greekpainters who matched talents with competingmurals? Zeuxis’s entry seemed perfect — somuch so that a bird took his bowl of fruit to bethe real thing and flew, fatally, into the wall.Moving down to Parhassius’s entry, the judgesdemanded that the artist pull back the curtainto let them see his entry. He could not, as thefamous tale goes, because the curtain waspainted. The bird, which had seemed to be thefinal line in the proof of Zeuxis’s excellence,drew attention to the analogous fatal flight ofthe judges “into the wall of illusion,” and soParhassius won, point, game, and match.What’s uncanny with the Parhassius story ishow the first half of the tale structures thesecond, and how the role of the viewers isundermined to re-write the rules of the game.The issues of self-reference and recursionmake the story uncanny in the same way thatthe word uncanny itself grows out of itsopposite and predecessor.In returning to Freud’s essay we find thecurious piece of literature that provides uswith a parallel opportunity of digression: E. T.A. Hoffman’s short story, “The Sand-Man.”The child Nathanael is frightened by a storyhis nurse tells to get him to go to bed, that a“Sand-Man” will be coming to collect eyes tofeed to the voracious children of the halfmoon. Burning with curiosity about themysterious late-night visits of his father’s

2lawyer, Coppelius (whose name means “eyesocket”), Nathanael conceals himself behind acurtain and witnesses strange ciousdeathfollowingonesuchexperiment, an older Nathanael is frightenedby an itinerate lens peddler, Coppola, whoresembles the lawyer. Coppola has conspiredwith a Professor Spalanzani to produce amechanizedautomaton,Olimpia,whomNathanael believes to be the professor’sbeautiful daughter. He falls in love until anargument between Spalanzani and Coppolaleads to the destruction of the doll. Nathanaelsuffers a nervous breakdown but slowlyrecovers, until a final encounter withCoppelius leads to his returned frenzy andsuicide.Freud lead us to two main themes inHoffman’s story: (1) optics — references toeyes, looking, and optical instruments andalso the role of Nathanael’s childhood spyingand his later “false witness” to Olimpia’shumanity; and (2) the crisis of identity,intensified in the involvement of theautomaton. Identity crisis is perhaps the mostrecognizable element in the uncanny ingeneral. Themes of the double, travel throughtime, mirrors, and the loss of self throughmistaken identity fill artists’ arsenals of thespooky. Optical themes claim the ancientpedigree of the evil eye, a nearly universalbelief in a generalized “being seen” where thelooker cannot be precisely located — adetachment of looking from geometric linesthat are usually drawn between the viewerand the viewed.Optics, identity crisis, and the automatontheme frequently team up in artisticproductions incorporating the uncanny. Forexample, in the cult film Dead of Night, nearlyevery episode involves this weird trio. A racecar driver recuperating from an accidentuncurtains his hospital window at night toreveal a daytime scene with a hearse whosedriver nods back to the coffin, saying, “Justroom for one inside, sir!” He recovers and isreleased, but on the way home he almostboards a bus whose conductor is a double ofthe hearse driver and who also says, “Justroom for one inside, sir.” With this omen, hebacks out of the bus, only to watch it crashdown an embankment seconds later.Another episode recounts the tale of a mirrorthat stubbornly reflects the room in which ithung for years, driving the new owner intoaccepting the invasion of the original owner’smurderous personality. In the last story, aventriloquist’s dummy “gets the upper hand”and drives his master to kill off his rival.Between the Two DeathsThe film’s entertaining display of the uncanny,like Hoffman’s fantastic story, makes it easyto underestimate the serious thematicstructures that connect the uncanny to thevisual dimensions architecture.We must“stick to a path” that leads from motif to rule.The first path is given by the most fantasticelement of the Hoffman story, the notion ofeyes out of their sockets. In literal form, thisis the scary tale of the Sand-Man who robschildren of their eyes to feed the half-moon’sbrood. Figuratively, the eye out of its socket isthe dreaming eye, the imaginary journey ofthe soul after death, or (less spectacularly)the eye of the audience, the reader, the artviewer who must “leave the body behind” inorder to enter into the illusion of art. In themythologies and folklore of every culture, thereason why Freud was so interested in theuncanny becomes clear: the dis-embodied eyeis the psyche, the soul. More precisely, it isthe soul “between the two deaths.”“Between the two deaths” is the intervalestablished by all cultures to separate thephysical death of the body from the imaginedpoint when the soul achieves rest. In manycases, the period is defined by the decay ofthe body, where typically an animal (worm,bird, dog, etc.), fire, or simply stone(sarcophagus “eater of flesh”) does the jobof reducing the body to dry bones. Theinterval between the two deaths alwaysinvolves uncertainty that is settled by magicintervention, prayer, or pre-schooling the soulto find its way through the labyrinthine puzzleof the underworld and answer the questions ofthe infernal deities.The eye separated from the body, the “organwithout a body,” as Slavoj Žižek would put itto get the better of Gilles Deleuze, is both thepre-analytical psyche, or soul, the migratinginitiate Freud encountered in museums andtravels. If we could hit the pause button ofpsychoanalysis at the point where Freud read

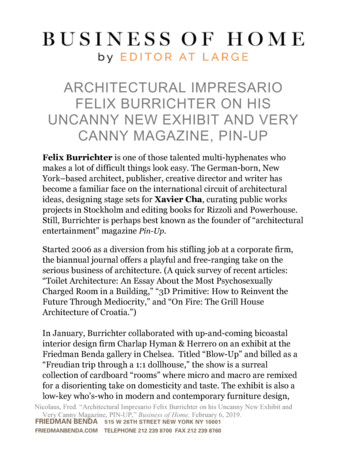

REVISITING THE UNCANNYMorelli’s essay on art authenticity, we mighthave diverted the young doctor towardscritical theory entirely.4 Or, if Freud had beenyoung at the time of World War II andmanaged to get to Maresfield Gardensdecades rather than a year before his death,we might imagine an encounter with AlanTuring, the inventor of the Bombe, or “EnigmaMachine,” used to decode German radiotransmissions. An early advocate of the ideaof artificial intelligence, Turing authored a testthat might have led Freud to add to his topicsof optics and identity a third, justified by thedoll Olimpia, that of the automaton.In a back-generation of history, we mightconsider that Freud would have improvedTuring’s famous test for machine intelligence,a proof that stated fundamentally that if youdon’t know that you’re talking to a machine,the machine for all goods and purposes is“thinking.” Freud might be particularlyinterested in one of the list of objectionsTuring listed in presenting his case forartificial intelligence: that of Lady Lovelace,the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, who,upon inspecting Charles Babbage’s protocomputer, the “analytical engine,” noted thata machine could not produce anything thatwas not placed in it to begin with. Thisobjection answers an important questionabout the human component of Turing’s test,played in Hoffman’s tale by Nathanael inconversation with Olimpia. Clearly, it wasn’twhat Olimpia said but what she didn’t say thatfascinated Nathanael and convinced him ofher wit, charm, and depth.Fig. 1. Freud’s desk, Maresfield Gardens, UK. Photoby author.3When Freud completed his examination of apatient, he returned to his desk to gaze intothe faces of a number of ancient figurines —images of gods that served much the samepurpose for centuries as Olimpia did forNathanael: the creation of a divine intelligencenot through expression but from silence (Fig.1). Here it must have occurred to him that theanalysand was “uncanny” in terms of whatpsychoanalysis revealed — that which oughtto have remained hidden; that which only an“automatic” process of concealment couldselect and order without the consciousknowledge of the subject; a double, residingwithin the mind, released by dreams, errors,and psychic trauma.The Master SignifierIn Lacan’s program of the mind, the “mastersignifier” is created as a kind of key metaphorthat is an “idea of ideas.” Not logical itself, itregulates the creation of subordinate ideasthrough a curiously reversed protocol. First,the signifier appears as a summation orabbreviation of a set of conditions, ideas, orobjects. Second, this set is seen to be thecause of the signifier. Third, in a completelyungrounded and irrational way, the directionis reversed, making the signifier the cause ofits own antecedent conditions.5Such master signifiers serve to “quilt” andstabilize ideas that normally slide past eachother. When quilting takes place, the resultingmaster signifier is not only durable, it is nearlyimpossible to eradicate. Žižek famously hasused the example of the film Jaws (1975).Here, the avarice of businessmen wanting tokeep the beach open at all costs, lewdness ofteenagers having sex in the water, and theencroachment of the beach on the domain ofnature are given as “prior conditions”summarized by the menace of the shark. Theconditions become causes, and then the sharkitself seen as the cause. By this Möbius-bandlogic, the shark must then be destroyed.Pristis delenda est!The issue of identity and even the “crisis ofidentity” is contained by the master signifierwith its contradictory means of stabilizingmeaning by de-rationalizing it. To model theprocess in the form of the syllogism, we havethe following: If (A)B and (B)C, then (A)C. “Ifall A are B” — that is, if a set of conditions canbe abbreviated by the master signifier ‘B’; and

4“if all B are C” — that is, if the master signifieris caused within the set of now-causalconditions; then all of the prior conditions arecaused, not causing, by means of anenigmatic element, ‘B’. The master signifiertakes the position of the “silent middle term,”the element that does not appear in theconclusion of the syllogism but is the meansof bringing together the idea of cause andreversed cause. If this middle is extracted —(B)B — it creates a “contradictory” set that is“contained by itself,” a statement of theGödelian paradoxical condition. The mastersignifier at one and the same time operates asa universal and a particular, cause and effect,victim and victimizer. But, it is most crucialthat this recursive, self-referential term beput, in the form of a “matheme” (reworkingthe Lacanian sense), into works of art, wherethe function of the master signifier, a flag ofthe “identity crisis” of the uncanny, can alsoguide themes of visuality. It would be evenmore interesting — or, rather, uncanny — ifthe function could be expounded to cover thecase of the automaton, the intelligence that isattributed to the machine by the user, theaudience, the spectator, the reader.From the Master Signifier to ‘Automaton’and AnamorphosisVidler recognizes the role of the automaton inthe uncanny but, good historian that he is, hedocuments Twentieth-Century examples andparaphrasestheirinteractionwitharchitecture. William Gibson (Neuromancer,1984) and Donna Haraway (Cyborg Manifesto,1991) are given a past (Surrealism, H. G.Wells) and a future (Diller and Scofidio). But,what constitutes a “present”? What are theactive ingredients and effective relationshipsthat make the automaton work?To fully activate the uncanny as a sourceinforming an architectural understanding ofvisuality, the issue of identity should be fullyunderstandable in terms of a theory ofautomata. This is important not just for the“anecdoctal” relationships where variations ofautomata occasionally relate, as in “The SandMan” and Surrealism’s examples, but for acomprehensive understanding of the spatialstructure required by the imagination in itstransposition of “hidden” contents from theviewer to the viewed.If Alfred Hitchcock, master of the uncanny infilm, can be asked to supply an example, wemight choose Strangers on a Train (1951). Atennis pro, Guy Haines, meets playboy BrunoAnthony on a trip t

The Architectural Uncanny , Essays in the Modern Unhom ely by Anthony Vidler is a satisfying and provocative work.1 Erudite, thorough, and grounded in the intellectual and urban history of modern Europe, it has the additional benefit of connecting a central architectural topic with one of psychoanaly sis’s most curious terms. There is, in short, little in Vidl er’s characteristically witty .