Transcription

Framework of actions to containcarbapenemase-producingEnterobacterales

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesAbout Public Health EnglandPublic Health England exists to protect and improve the nation’s health andwellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. We do this through world-leadingscience, research, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships andthe delivery of specialist public health services. We are an executive agencyof the Department of Health and Social Care, and a distinct deliveryorganisation with operational autonomy. We provide government, localgovernment, the NHS, Parliament, industry and the public with evidencebased professional, scientific and delivery expertise and support.Public Health EnglandWellington House133-155 Waterloo RoadLondon SE1 8UGTel: 020 7654 8000www.gov.uk/pheTwitter: @PHE ukFacebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEnglandPrepared by: Colin Brown and Carole Fry (edited by Rachel Freeman andSusan Hopkins)For queries relating to this document, please contact: hcai@phe.gov.uk Crown copyright 2020You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in anyformat or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. Toview this licence, visit OGL. Where we have identified any third partycopyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyrightholders concerned.Published September 2020PHE publicationsgateway number: GW-1625PHE supports the UNSustainable Development Goals2

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesContentsExecutive summary5Key recommendations6Section 1. Context and background81.1 Rationale for update1.2 Document scope1.3 What are carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales?1.4 Importance of controlling CPE1.5 Implementation of the CPE Framework: benefits and costs889910Section 2. Who to screen and why132.1 Introduction2.2 Active screening for CPE2.3 Key risk factors for CPE colonisation or infection2.3.1 Admission screening to acute care providers2.3.2 On-going screening2.3.3 Definition of a close contact for screening purposes2.3.4 Screening outside of acute care2.4 Outbreak screening strategy2.5 Screening swabs2.6 Staff screening13141414171818181920Section 3. Monitoring and surveillance213.1 Introduction3.2 Surveillance systems3.3 Monitoring3.4 Reporting of surveillance data to Public Health England21212222Section 4. Minimising transmission244.1 Introduction4.2 Standard infection control precautions and contact precautions4.3 Visitors4.4 Isolation4.5 Cohorting4.5.1 Where cohorting is not an option4.5.1 Other settings4.6 Patient movement4.7 Decolonisation of patients4.8 Non-acute care settings24252727282829293030Section 5. Cleaning and decontamination315.1 Introduction5.2 Decontamination following patient/resident discharge5.3 Sinks, basins, showers and drains5.4 Endoscopes331323334

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesSection 6. Antimicrobial prescribing and stewardship6.1 Introduction6.2 General principles6.3 Monitoring6.4 Responding to increased antibiotic consumption trends6.5 Treatment and surgical prophylaxis options6.6 ‘Horizon scanning’ for new antimicrobialsSection 7. Laboratory methods36363737383838407.1 Introduction7.2 Detection of CPE in diagnostic laboratories4040Section 8. Managing CPE outbreaks and clusters428.1 Introduction8.2 Risk assessment in non-acute settings8.3 Ongoing transmissionSection 9. Organisational responsibilities424343449.1 Introduction9.2 Leadership, planning and implementation9.3 Communication9.4 Repatriations from abroad44444545Glossary of terms46Working group and acknowledgements48References50Appendices - Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producingEnterobacterales59Appendix A: International guidance comparison60Appendix B: CPE – Think RISK61Appendix C: Risk prioritisation of infection prevention and control measures,screening and isolation62Appendix D: How to conduct a risk CPE assessment in non-acute settings63Appendix E: Acute care – flow chart of infection prevention and control measuresto contain CPE64Appendix F: Risk assessment tool for isolating CPE-positive patients (whenisolation room capacity is limited)65Appendix G: Containing CPE in a paediatric setting66Appendix H: Antimicrobial stewardship tools and resources68Appendix I: Considerations when managing an outbreak of CPE in acute caresettings69Appendix J: Primary care quick reference guide71Appendix K: explanations that can be used in local patient information materials 73Appendix L: CPE patient-held card784

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesExecutive summaryThis framework focuses on carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales(CPE); these organisms spread rapidly in healthcare settings and lead topoor clinical outcomes because of limited therapeutic options. The increasedincidence of CPE has significant cost and operational implications forhealthcare providers.Unless action is taken and we learn from experiences elsewhere in the world,rapid spread of CPE will pose an ever-increasing threat to public health andmedical treatment pathways in the UK.The framework sets out a range of measures, that if implemented well, willhelp health and social care providers minimise the impact of CPE. Theseinclude: active patient admission screening of risk groups rapid detection of patients colonised or infected with CPE, withappropriate surveillance systems to enable ongoing monitoring consistent implementation of infection prevention and control practicesand contact precautions minimisation of CPE reservoirs by effective environmental cleaning anddecontamination antimicrobial stewardship programmes to minimise inappropriate use ofbroad-spectrum antibiotics, including carbapenems optimised laboratory methods to detect carbapenemase-producing Gramnegative bacteria, including Enterobacterales prompt recognition of outbreaks to enable effective management organisational ownership to support the implementation of this frameworkWe recognise that the evidence base for some recommendations is limitedand that local risk assessment is important for building a CPE policy relevantto the local situation that can be implemented based on the Framework.Where there is an evidence base we have referred to this explicitly, otherrecommendations are based on expert guidance or opinion.5

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesKey recommendationsBased on this developing evidence base there are eight areas with corerecommendations that all settings should introduce or further develop:Framework of actions to contain CPE in health and social care settings active screening for CPE is recommended toPatientminimise transmission from CPE positive patientsscreening* patient screening, the scope of which should beguided by local and regional prevalence, specificpatient populations and risk factors, must beimplemented alongside infection prevention andcontrol interventions surveillance systems are needed to rapidly detectSurveillanceand monitor patients either colonised or infectedwith CPE consistent implementation of standard infectionStandardcontrol precautions and contact (transmissioninfection controlbased) precautions should be employed to reduceand contactthe spread of CPEprecautions enhanced cleaning processes are required whenCleaning andCPE positive patients are detecteddecontamination this must be undertaken before disinfection antimicrobial usage and audit data should beAntimicrobialreviewed at regular intervals by local antimicrobialstewardshipstewardship committees (or equivalent)(AMS) specific actions should be taken where there areearly signals of increasing antimicrobial resistanceor antimicrobial consumption trends, particularlybroad-spectrum agents including carbapenems implement molecular or immunochromatographicLaboratoryassay in frontline diagnostic laboratories for themethods*detection of KPC, OXA-48-like, NDM and VIMcarbapenemases to complement culture-basedtesting refer carbapenem resistant isolates with localnegative tests to detect IMPs and other rarercarbapenemase families to PHE’s AntimicrobialResistance and Healthcare-Associated InfectionsReference Unit6

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesOutbreaks andclusters Organisationalresponsibilities a prompt response following detection of CPE inhealth/social care settings is required to minimiseonwards transmissionenvironmental samples should only be takenwhen epidemiologically indicatedorganisational leadership should support theinfection prevention and control programme byproviding organisational and administrativesupport.*not applicable outside of acute providers of care7

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesSection 1. Context and background1.1 Rationale for updateThis document is an update of the Acute trust toolkit for the early detection,management and control of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae 1 andthe Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: non-acute toolkit. 2Stakeholders had requested one document to replace the two toolkits that providesa framework of actions for all health and social care providers in a simplified format.An evaluation of the acute toolkit was undertaken in 2016 (1). The results of thishave informed the development of this framework. The objectives of the frameworkare to: provide a framework of actions and tools to support health and socialcare providers support development of local guidance and tools for the earlydetection of CPE with the aim of preventing transmission andcontaining their spread for the safety of patients and the widerpopulation direct health and care professionals to the relevant guidelines forlaboratory methods, including reporting of results to PHE1.2 Document scopeThere is significant uncertainty regarding the most effective measures to minimisethe transmission of CPE, and the evidence base is constantly evolving. Thisframework aims to provide health and social care organisations with a useful andpragmatic set of actions to support the implementation and monitoring ofinterventions to prevent and control the spread of CPE.This document refers to CPE alone; although some interventions may becommon to other carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria such ascarbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp., these arenot included within the document given the differences in epidemiology,microbiology, transmission, and environmental persistence. In 2017, theWorld Health Organisation produced detailed guidance (2) on prevention andcontrol of these organisms in healthcare settings, in addition to rnment/uploads/system/uploads/attachment data/file/329227/Acute trust toolkit for the early v.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment data/file/769414/CPE-Non-AcuteToolkit CORE.pdf8

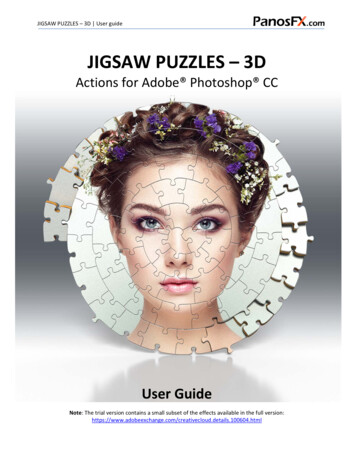

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesMany elements of the framework are equally applicable to all providers ofhealth and social care; where actions relate to a specific sector this will beclarified.1.3 What are carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales?Recent taxonomy changes have included the family Enterobacteriaceaewithin the order Enterobacterales. Enterobacterales are a large family ofbacteria that usually live harmlessly in the gut of humans and animals. Theyinclude species such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp. and Enterobacterspp. However, these organisms are also some of the most common causesof infections, including urinary tract infections, intra-abdominal andbloodstream infections.Carbapenems are a valuable family of β-lactam (penicillin-like) antibioticsnormally reserved to treat serious life-threatening multidrug-resistant Gramnegative infections in hospitals. They include meropenem, ertapenem,imipenem and doripenem.Resistance to some or all carbapenems is an intrinsic (natural) characteristicof some Gram-negative bacteria. Others can produce carbapenemases,which are enzymes that destroy carbapenem antibiotics, conferringresistance. This document focuses on acquired carbapenemases, aparticular concern as these genes (usually located on mobile elements suchas plasmids) can move vertically (within a strain) and horizontally (betweenstrains, species and genera).Enterobacterales producing acquired carbapenemases are referred to asCPE. KPC, OXA-48-like, NDM, VIM, and IMP enzymes are the mostprevalent enzymes in the UK. Increasing gut colonisation with these resistantbacteria will inevitably lead to an increase in difficult-to-treat infections. Figure1 illustrates the relationship between CPE and other carbapenem-resistantand carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria.1.4 Importance of controlling CPEUnless action is taken and lessons are learnt from experiences elsewhere inthe world (see Appendix A for guideline comparison), rapid spread of CPEwill pose an increasing threat to public health and medical treatmentpathways in the UK. These resistant bacteria can spread rapidly inhealthcare settings. Almost all acute healthcare providers in England have9

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteralesidentified at least one new patient colonised with CPE in the last year; atleast half have identified multiple positive patients (3).Invasive infections with CPE increase both patient length of stay, as aconsequence of morbidity, and mortality, compared to bacteria not carryingresistance markers (4, 5). Additionally, large outbreaks in the UK have led tosubstantial costs (both healthcare, staffing and other resources) given thetime taken to achieve control once the outbreak is established. In somehealth and social care organisations in England, CPE are now endemic.An understanding of local epidemiology and context is key, as public healthactions will differ depending on: the prevalence of CPE in patients being admitted to healthcare settings prior outbreaks within the region the patient population mix including number of overseas patients orrepatriations of patients from hospitals abroad individual risk assessments of areas where transmission is most likely tooccurHealthcare providers who have considerable experience of CPE outbreaksmay develop contextualised screening strategies reflecting their localepidemiology.1.5 Implementation of the CPE Framework: benefits and costsThe operational challenges of implementing this framework cannot beunderestimated. It will require board and senior management levelcommitment and support to ensure capital and recurrent funding required tosustain the range of recommended interventions.It is widely acknowledged that the cost of managing episodes of CPE inhealthcare settings can be considerable. A US study estimated the cost ofmanaging a single case to be between 22,484 to 66,031 for hospitals (6).A European study that assessed the cost of implementing strict measures toeradicate multi-drug resistant infections (including CPE) estimated that thisranged from 285 to 57,532 per positive patient (7). One UK studyestimated the cost of a CPE outbreak where 40 patients identified as infectedor colonised over 10 months at 1 million (8). The cost included the actualexpenditure to control the outbreak as well as the “opportunity” costs such aslost revenue due to ward closures.Modelling work from Canada suggests universal CPE screening is potentiallycost-effective, even at a lower prevalence than currently reported in England,10

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteralesand identified conditions where a colonised patient infects one other patientat a very low prevalence under which it would become cost saving comparedto not screening (9). More generally, it is expected that suitable selectioncriteria would enhance the cost-efficiency of screening.While there are no studies determining the optimal measures to prevent and controlCPE, managing CPE outbreaks carries considerable costs – financial, logistical, andreputational.11

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesFigure 1: Explanation of different terminology for various carbapenem resistance mechanisms and nomenclatureCarbapenem-resistantGram negative bacteriacan be naturally resistantto carbapenems such asStenotrophomonasmaltophilia OR theycan acquirecarbapenemase genes,which typically (but notalways) confercarbapenem resistance.Carbapenem-resistantEnterobacterales (CRE)refers to a particular typeof Gram negative bacteria.Resistance can be causedby carbapenemases,which would make themcarbapenemase producingEnterobacterales (CPE).There are also othercarbapenemase producingnon-EnterobacteralesGram negative rods.ExamplesCarbapenem-resistantGram cteralesGram negative nt Gramnegative bacteria: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Pseudomonas aeruginosa withOprD porin loss effluxCarbapenemase-producing nonEnterobacterales Gram negativerods: Acinetobacter baumanniiproducing OXA-23carbapenemase Pseudomonas aeruginosaproducing VIM carbapenemaseCRE: Enterobacter cloacae resistant tocarbapenems but does not havea carbapenemase geneCPE: E. coli producing NDMcarbapenemase Klebsiella pneumoniaeproducing KPC carbapenemaseCPE are regarded as the biggest threat as the resistance genes can transmit vertically and horizontally,thereby rapidly spreading between different strains of bacteria.CRE carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. CPE carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales. KPC Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase.OXA OXA carbapenemase. NDM New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase. VIM Verona Integron-Mediated metallo-β-lactamase.* Modified from ‘Antimicrobial Resistance & Prescribing Programme (HARP team), Public Health Wales. All Wales Guidance for Developing Policies and12Procedures to Manage Multi Drug Resistant Organisms(MDRO) including MRSA. Cardiff: PHW, 2018’.This is a visual representation and circle size/alignment may not fully represent specific characteristics.

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesSection 2. Who to screen and whyBox 1: New evidence and recommendations for screening patients forCPENew evidence since publication of previous guidance Patients are colonised with CPE prior to developing an invasiveinfection (10-12). The aim of active screening is to prevent transmissions and the numberof colonised patients at risk of invasive infection. 3 CPE screening can be cost effective (9). Serial admission screening for CPE does not improve the rate ofdetection (13). Identifying patients colonised with CPE is optimised by taking rectalswabs (14). Increasing evidence of colonisation with CPE following travel abroad(10, 15-18).Key recommendations Acute care providers should actively screen patients at risk ofcolonisation. Screening strategies (including ongoing screening) should be based onlocal epidemiology and patient mix. Close contacts of cases should be screened. Enhanced screening should be conducted during outbreaks. Rectal swabs should be taken for screening purposes (include woundsand urine [if catheterised]). Include CPE status (ie positive/negative) on discharge summary ifpatient has been screened during admission. Screening of staff is not recommended.2.1 IntroductionColonisation usually precedes infection. Early identification of patientscolonised or infected with CPE can help minimise transmission and informtherapy and early interventions to prevent invasive infections. (9-11, 19).3 Approximately 1 in 200 patients with ESBL colonisation progress to ESBL blood stream infectioneach year; applying similar proportions to CPE, with the currently detected 100 BSI each year thereare approximately 20,000 colonised patients in England.13

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales2.2 Active screening for CPEEach patient should have a clinical risk assessment to determine those athigher risk of CPE colonisation on admission, readmission or transfer fromanother healthcare facility (20). Active screening for CPE is recommended to: minimise transmission from CPE positive patients minimise the risk that colonised patients will develop clinical infections egfrom invasive devices ensure appropriate surgical prophylaxis and prescribing of effectiveantibiotic therapy if clinical infection develops (see section 6.5) minimise environmental contamination and the development of potentialreservoirsNote: Healthcare providers may wish to treat patients that have beenpreviously identified as CPE positive as persistently colonised regardless ofscreening, though the evidence base for this is limited and is likely to changeas knowledge evolves.The evidence to inform CPE screening strategies is limited and therecommendations included in this framework are consistent with internationalguidelines (2, 20-23) and UK expert consensus.2.3 Key risk factors for CPE colonisation or infection2.3.1 Admission screening to acute care providersAcute trusts will need to make their own risk assessment based on regionalprevalence, patient mix, and linkages with other care providers.The following patients should be strongly considered for screening onadmission if they are likely to stay in hospital overnight (22, 24), if: in the last 12 months, they have: been previously identified as CPE positive (13, 25, 26)4 been an inpatient in any hospital, in the UK or abroad (25, 27-30) had multiple hospital treatments eg are dialysis dependent (25, 29,31) had known epidemiological link to a known carrier of CPE (25, 32)A previously positive patient may be negative on the first screen but may become positive later inadmission eg after a course of antibiotics.414

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales they are admitted into augmented care or high-risk units (29, 33-35)(see Box 2).Box 2: Definition of augmented care/high risk settings and comorbidities(adapted from DH MRSA 2014 and Water systems - Health TechnicalMemorandum 04-01)For the purposes of this document, the patient groups in augmentedcare/high risk scenarios include: those patients who are severely immunosuppressed because ofdisease or treatment: this will include haematology/oncology andtransplant patients and similar heavily immunosuppressed patientsduring high-risk periods in their therapy those cared for in units where organ support is necessary, forexample critical care (adult, paediatric and neonatal), renal(including dialysis settings), respiratory or other critical care orintensive care situations those patients who have extensive care needs such as liver unitsand patients with breaches in their dermal integrity, such as inthose units caring for burnsAn increased prevalence of CPE in a hospital in the same region (specificallywith the same referral network of patient referrals) increases the risk ofpositivity (36).Based on the epidemiology of the admission unit, patients that may be at anincreased risk and should also be considered for screening include those: with immunosuppression (29) with exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotic courses (such ascephalosporins, glycopeptides, and piperacillin/tazobactam) (31, 34),and in particular carbapenems (29) within the past one month (37),not covered in other risk groups eg those receiving OPAT admitted from Long Term Care Facilities where higher levels ofinterventional care are provided eg long-term ventilation (24, 29)There is also increasing evidence that international travel is a risk foracquisition of resistant Gram-negative organisms including CPE in manycountries across Europe (10, 15, 37), including the United Kingdom (16), andparticularly from the Asian subcontinent (17, 18). Though this does not formpart of taking a routine patient history outside of infectious disease settings,acute healthcare providers should make efforts to capture this informationwhen conducting admission screening risk assessments.15

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing EnterobacteralesAppendix B provides a reminder acronym for admission screening and Figure2 provides a summary for admission and on-going screening strategies.Routine screening for primary care settings or on admission to a care orresidential home is not recommended. Acute healthcare providers need toundertake a risk assessment to determine if other groups of patients requireadmission screening based on the local incidence of CPE, patient acuity, thelevel of care, interventions and carbapenem usage.It is usually not feasible, due to a lack of single rooms, to place patients inpre-emptive isolation whilst waiting for the result of their screen (38, 39).When a single room is not available, use standard infection controlprecautions (SICP) and contact (transmission based) precautions in a multioccupancy bay setting until screening results available (see Section 4 fordetail). Local risk assessment will determine which patients are priority for asingle room eg patients transferred from hospitals overseas (see AppendixC).Active screening for CPE carriage is not usually required in outpatientdepartments or ambulatory care unless there is evidence of transmission inthese settings. However, CPE status should be recorded on the dischargesummary and/or patient transfer documents if the patient has been screenedduring their admission.Figure 2: Algorithm for admission and on-going screening strategiesType ofscreeningAdmissionscreeningAll admissionsto high-riskunitsRiskassessment ofadmissionsoutside highrisk unitsOngoingscreeningWeekly/monthlyscreening ofpatients in highrisk unitsScreeningrelated tooutbreakinvestigationScreening ofcontacts16Weeklyscreening ofwards followingan outbreak

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales2.3.2 On-going screeningThe evidence base to inform on-going screening strategies is limited,however the options listed below may help local decision making.There is evidence that serial admission screening (repeat screeningseparated by specified time points) for CPE does not improve the rate ofdetection. However, repeat screening of long-stay patients may improve theidentification of antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (13).Repeated screening of individual patients may detect patients who werepreviously not recognised as carrying CPE in certain situations such as forlong stay patients on augmented care/high risk units, on units where there ishigh usage of carbapenem antibiotics or in a setting of transmission (26, 40,41) 5. Some trusts have implemented repeat screening after 28 days in theirhigh-risk areas. However, implementing repeated screening of individualsbased on their length of stay is challenging, therefore some high-risk unitsundertake weekly or monthly screening to ensure early detection of newcases of CPE. Periodic point prevalence studies of these units are analternative approach advocated by other guidelines (21, 23).Once an in-patient is found to be CPE positive, no further screening isnecessary during their inpatient stay, as repeated screens of the samepatient usually remain positive for CPE over the course of a singlehospitalisation (42). CPE carriers should be clearly identified on patientrecords or electronic systems (case flagging). The patient’s GP should alsobe informed about their colonisation or infection status by the provider ofservices who took the sample, and this information should also be includedon any inter-hospital transfer information or for a future admission to anotherhospital.Evidence suggests that colonisation with CPE extends at least through asingle hospitalisation and could extend between multiple hospitalisations (42,43), although a recent paper found that three quarters did not havedetectable CPE on readmission screening (26).For more detailed information on the burden of carbapenem resistance see the English surveillance programmefor antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) ation-andresistance-espaur-report517

Framework of actions to contain carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales2.3.3 Definition of a close contact for screening purposesA CPE contact is defined as a patient who has been in direct (for exampleperson-to-person contact) or indirect contact (for example contact withcontaminated environment or equipment) with another patient who is affectedby CPE (infected or colonised) and is therefore at risk of CPE carriage andshould be screened.The definition of a CPE contact will depend on several factors, including: the setting clinical scenario type and length of exposureCPE contacts are most commonly defined as having shared the sameclinical space (eg bay or less commonly ward) as a known CPE carrier.Outside the hospital environment these could also include a person living inthe same house or care home, or sexual partner.2.3.4 Screening outside of acute careOutside of the acute care sector, screening strategies should be based onthe local epidemiology, patient acuity and level of interventions, such as longterm ventilation and rehabilitation facilities (see Appendix D). PHE HealthProtection Teams can assist with local risk assessments. They can also liaisewith Local Authority Health Protection Team/Community Infection Preventionand Control Team where these exist.2.4 Outbreak screening strategyBay or unit contacts of patients newly identified as CPE positive need to bescreened to detect possible transmission as further carriers may be detected.The number of contacts to be screened will be determined by the

1.4 Importance of controlling CPE 9 1.5 Implementation of the CPE Framework: benefits and costs 10 Section 2. Who to screen and why 13 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Active screening for CPE 14 2.3 Key risk factors for CPE colonisation or infection 14 2.3.1 Admission screening to acute care providers 14 2.3.2 On-going screening 17