Transcription

The Transformation of Corporate Bond Investors and Fragility:Evidence on Mutual Funds and ETFsCaitlin DannhauserVillanova UniversitySaeid HoseinzadeSuffolk UniversityThe liquidity transformation of mutual funds and exchange‐traded funds (ETFs) is examined asa potential source of corporate bond market fragility. Using differential exposure among bondsfrom the same issuer to plausibly exogenous outflows, ETFs cause temporary flow‐driven yieldpressure that reverts after seven months. Outflows from active and index mutual funds have noimpact. The differential effects are attributed to short‐term positive feedback traders’ presence inETFs and delayed arbitrage propagating shocks. A one‐month effect is found for active mutualfunds in the lowest quartile of liquid assets, suggesting their significant liquidity buffers may beinsufficient in prolonged shocks.Caitlin Dannhauser is at the Villanova School of Business, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA19085. She can be reached at caitlin.dannhauser@villanova.edu. Phone: 610‐519‐4348. Saeid Hoseinzade is at theSawyer Business School, Suffolk University, 120 Tremont Street, Boston, MA 02108. He can be reached at Email:shoseinzade@suffolk.edu . We thank Itay Goldstein (discussant), Antti Petajisto (discussant), Pierluigi Balduzzi,Jeffrey Pontiff, Jonathan Reuter, Ronnie Sadka, Hassan Tehranian, and participants at the 2017 ICI and DardenAcademic and Practitioner Symposium on Mutual Funds and ETFs, the Second Annual “Philly Five” FinanceSymposium, and Suffolk University Seminar Series for helpful comments.

1. IntroductionFragility resulting from the unintended consequences of financial innovation is a recurringtheme in market history (Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny, 2012).1 With a heightened interest invulnerabilities created by various non‐bank financial institutions, Schmidt, Timmermann, andWermers (2016) observe that pooled vehicles for which the liquidity mismatch becomes magnified intimes of turmoil are particularly susceptible to run‐like behavior and its consequences. A more recent,yet prevalent investment theme is the transformation of the systemically important corporate bondmarket. Between 2008 and 2016 the amount of corporate debt outstanding grew 56% according to theSecurities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). Over the same period, FederalReserve Board statistics reveal that broker‐dealer corporate and foreign bond holdings decreased 78%,while those of nontraditional investors, exchange‐traded funds (ETFs) and open‐end mutual funds,more than tripled. With combined holdings nearly matching the levels of traditional long‐term bondinvestors, insurance companies, historically familiar concerns regarding the intraday and dailyliquidity provisions of ETFs and mutual funds relative to illiquid corporate bonds have emerged.2 Forexample, the 2015 Financial Stability Oversight Council annual report lists the expansion of thesevehicles as a potential threat and Bill Gross warned of a mass exodus through ETFs.3 Conversely, suchrisks are deemed limited by the Investment Company Institute due to mutual funds use of a liquiditybuffer and by ETF sponsors due to structural features that reduce their interaction with constituentbonds.4,5 Given the importance of corporate debt to firms and the growing relevance of theseinvestment vehicles to investors’ portfolios, this paper contributes to the literature by cleanlyidentifying the asset price implications of flows from corporate bond ETFs and mutual funds duringa period of turmoil.Collateralized mortgage obligations in the 1980s and 1990s, mortgage backed securities in the 2000s, and money market funds in2008 motivate the theory that excessive issuance of innovations sparked by virtues of diversification, tranching, or insurance prior tothe revelation of the securities’ vulnerability to unattended risk results in market fragility.2Bloomberg characterize the change in the post‐crisis bond market model as a transition of power from banks to mutual funds,hedge funds, and exchange‐traded funds. They state that regulations have paved the way for the buy‐side “to exert more influence1than ever on markets.” See: ��15/the‐rise‐of‐the‐buy‐side“The obvious risk—perhaps better labeled the ‘liquidity illusion’—is that all investors cannot fit through a narrow exit at the sametime,” Bill Gross. See: ns‐bond‐etf‐party‐14969250004 ICI 2016 Factbook states “There are many reasons to believe [concerns that outflows to bond funds could pose challenges for fixed‐income markets] are overstated.” See: Site%20Properties/pdf/2016 factbook.pdf5 Bill McNabb, CEO of Vanguard, states “This discovery that most ETF share trading does not lead to any activity in the ETF portfoliomeans the impact of ETFs — and the possibility of disruption or volatility — on the primary market is limited.” 1e6‐893c‐082c54a7f53931

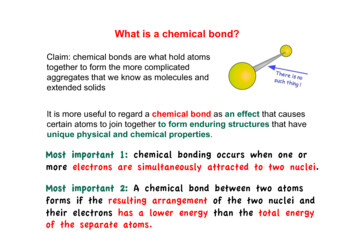

Although ETFs and mutual funds are both pooled investment vehicles that provide diversifiedexposure to the difficult to access over the counter (OTC) underlying market, their distinguishingfeatures make the mechanism through which outflows from the funds can impact the pricing of theunderlying distinct. For mutual funds, investors can redeem shares for cash at the end of day net assetvalue (NAV) leaving the remaining investors to bear the consequences of another’s outflow, thuscreating the potential for runs induced by strategic complementarities. Goldstein, Jiang, and Ng (2017)find that active corporate bond mutual funds are particularly susceptible due to a concave flow toreturn relationship. The authors conclude that for these funds to be a major systemic concern evidenceof an effect on market prices and potentially real economic activity is needed.The distinguishing features of ETFs mitigate concerns of similar runs because the redeemingshareholder bears the cost of his own actions. Nevertheless, recent theoretical works suggests that theabsence of these externalities does not preclude ETFs, from being a potential source of market fragility.Focusing on ETFs backed by hard to trade assets, Bhattacharya and O’Hara (2016) claim that ETFs arenow a preferred trading vehicle capable of affecting underlying asset prices. Their model predicts thatETFs can exacerbate market instability and herding due to imperfect learning and delayed pricesynchronization. The authors, along with a broader ETF model from Malamud (2016) shows that thecreation and redemption mechanism of ETFs can serve as a shock propagation channel. Finally, Panand Zeng (2017) theorize that the dual role of authorized participants (APs) as corporate bond marketmakers and arbitrageurs creates conflicting incentives that increase fragility.The challenge of addressing the effect of turmoil period outflows from nontraditionalcorporate bond investors on market yields is that the majority of asset growth has occurred duringthe post‐crisis bull market, limiting the number of unanticipated exogenous shocks. However, in thesummer of 2013 the Federal Reserve unexpectedly proposed ending its bond buyback program knownas quantitative easing (QE). The change in expectations about monetary policy led investors to altertheir perception of risk and to sell their bond fund holdings, in an episode commonly referred to asthe Taper Tantrum. According to Lipper, the uncertainty in timing and scope of the Fed’s QEwithdraw led to 8.6 billion in outflows from taxable bond mutual funds and ETFs in the weekfollowing the announcement and 23.7 billion over four weeks, the sharpest four‐week exodus since2008. The turmoil and outflows continued throughout the summer, forcing the Fed to officiallyannounce in September that it would delay any QE slowdown.2

Using this plausibly exogenous shock as a quasi‐natural experiment, we follow Coval andStafford (2007), Lou (2012), and Mitchell, Pulvino, and Stafford (2004) by studying if outflows fromeither vehicle during a period of turmoil create yield pressure that subsequently reverses. Beyondcontrolling for observable bond characteristics and liquidity, the inclusion of issuer level fixed effectsis key to our identification similar to Manconi, Massa, and Yasuda (2012). Relying on within issuervariation, endogeneity concerns regarding changes in fundamental risk are addressed by effectivelycomparing two bonds from the same firm exposed to different levels of outflows. We find significantyield pressure created by ETFs, with a one standard deviation increase in ETF Tantrum outflowsleading to a 12.4 basis point greater increase in the yield spread of corporate bonds in September 2013.Economically, this implies a 10.8% (8.5%) increase in the yield spread of the median (mean) corporatebond held by ETFs prior to the onset of the Taper Tantrum. The effect is transient lasting seven monthsbefore reverting, thus implying that bonds temporarily traded at non‐fundamental values due to ETFoutflows. In contrast, we document that outflows from active mutual funds have no significant effecton corporate bond yield spreads in the months following the Taper Tantrum. Since the index strategyof most ETFs reduces the flexibility of a manager’s response to flows (Christoffersen, Keim, andMusto, 2008; Elton, Gruber, and Busse, 2004), we also consider the impact of index mutual funds. Wefind that Taper Tantrum outflows from index mutual funds do not have a significant impact on theyield spread of their holdings. The insignificance of an index mandate may reflect the use ofrepresentative sampling or mutual funds benchmarking to aggregate bond indices, rather than to thecorporate bond dedicated indices followed by ETFs.Next, we attempt to identify which characteristics of ETFs contribute to the distinctive yieldimpact. In particular, we examine the appeal of intraday trading to different investor types and theimplications of the in‐kind creation and redemption mechanism. First, as described by Chordia (1996),Deli and Varma (2002) and Nanda, Narayanan, and Warther (2000) funds adopt different structuresto appeal to the stochastic liquidity needs of investors. Following Amihud and Mendelson (1986),Constantinides (1986) and Poterba and Shoven (2002), we posit that the intraday liquidity of ETFs islikely to attract short‐term traders who are theorized to focus on the behavior of other investors, ratherthan on long‐term fundamentals (Allen, Morris, and Shin, 2006; De Long, Shleifer, Summers, andWaldmann, 1990a; Froot, Scharfstein, and Stein, 1992; Stein, 2005). As described by Cella, Ellul, andGiannetti (2013), during normal markets short‐horizon investors in ETFs should not affect underlying3

bonds because other investors readily provide liquidity. However, in turmoil periods short‐horizoninvestors are expected to sell en masse (Bernardo and Welch, 2004; Morris and Shin, 2004).The distribution of fund flows provides preliminary evidence of distinct investor bases in thedifferent investment vehicles. We follow the literature to formally test if the underlying ETF investorshave shorter investment horizons by considering the volatility of fund flows (Bollen, 2007; Sialm,Starks, and Zhang, 2015) and the churn of institutional investors (Cella, Ellul, and Giannetti, 2013) . Inboth the cross‐sectional regressions of Sialm, Starks, and Zhang (2015) and panel regressions with datefixed effects, we find that the volatility of ETFs is statistically significantly greater than mutual fundsafter controlling for lagged fund characteristics. Next, we focus on a subset of investors in thecorporate bond funds in our study, institutional investors. We find that the churn of institutions thatuse corporate bond ETFs is statistically significantly shorter than those that use mutual funds. Havingestablished that short‐term investors self‐select into ETFs, we then examine if they engage in positivefeedback trading, that is investors increasing flows in periods of lower interest rates and decreasingflows in periods of higher interest rates. Specifically, we regress flows on lagged changes in Treasuryrates, an ETF dummy, and their interaction, as well as, controls for lagged fund flows, returns,turnover, expense ratio, and the average rating and duration of its holdings. The coefficient on theinteraction term is negative and significant, implying that ETF investors are more sensitive to commonmarket shocks and trade on past price trends, which is theorized by De Long, Shleifer, Summers, andWaldmann (1990b) to be potentially destabilizing. Overall, these results provide evidence that bondsexposed to ETFs are subjected to distinct pressures associated with short‐horizon positive feedbacktraders.Second, while mutual funds deal directly with all investors through fund share and cashtransactions, ETFs interact only with APs through the in‐kind creation and redemption mechanism,known as the primary market. ETF creation (redemption) occurs when an AP buys the pre‐specifiedbasket (ETF shares) and exchanges it for a block of ETF shares (underlying basket). The reliance ofETFs on this mechanism has important implications for both portfolio construction and arbitrage.Because ETFs generally do not need to provide cash on demand they may invest more in benchmarksecurities. In contrast, for various types of mutual funds Chen, Goldstein, and Jiang (2010), Chernenkoand Sunderam (2016) and Hoseinzade (2015) show that managers have an incentive maintain aliquidity buffer to mitigate the adverse effect of investor flows, particularly during periods of4

volatility. Comparing the asset allocation in the reporting period prior to the Taper Tantrum, we findthat the median investment in cash and government bonds is 21.2% for active mutual funds and 47.7%,for index mutual fund, compared to just 2.74% for ETFs, a difference that is both statistically andeconomically significant.The primary market also enables APs to engage in arbitrage between the ETF market priceand NAV. While arbitrage should be instantaneous, when ETFs are backed by hard to trade assets itmay not be the case (Bhattacharya and O’Hara, 2016). However, a difference in the two prices mayoccur and persist if limits to arbitrage are present (Abreu and Brunnermeier, 2003; De Long, Shleifer,Summers, and Waldmann, 1990a; Ofek and Richardson, 2003; Pontiff, 1996; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997).A number of theories further suggest that in the presence of limits arbitrage may amplify rather thanstabilize fundamental shocks (Greenwood and Thesmar, 2011; Hong, Kubik, and Fishman, 2012;Hugonnier and Prieto, 2015; Kyle and Xiong, 2001). We begin by documenting that ETF arbitrage wasimpaired. Splitting corporate bond ETFs into two groups based on the average percentage price toNAV deviation during the turmoil period we show that the high deviation ETF group, those for whichETF sellers pushed market prices significantly below the underlying NAV, traded at slight premiumsprior to the event. Comparing the characteristics of the ETF groups immediately before the TaperTantrum shows that both are similar size and hold bonds with similar credit quality, volatility of flowsand institutional ownership. The high deviation ETFs hold bonds with greater effective duration forwhich we would expect more selling pressure for in expectation of higher interest rates and havehigher bid ask spreads suggestive of known limits to arbitrage (Gromb and Vayanos, 2010).Interestingly, there is an insignificant difference in the AP arbitrage activity proxy from Da and Shive(2013) prior to the event, but arbitrage in the high deviation ETFs is statistically significantly lowerduring the Taper Tantrum.The existence of these arbitrage opportunities translates into potential selling pressure for theindividual bonds from arbitrageurs, who are concerned about relative price efficiency, rather than theabsolute price efficiency of the individual assets (Brown, Davies, and Ringgenberg, 2016; Mitchell,Pedersen, and Pulvino, 2007). We first calculate the holdings‐weighted exposure of each bond held byETFs to price‐NAV deviations during the tantrum, denoting those with below median measures higharbitrage exposure as they are held by ETFs trading at Taper Tantrum induced discounts. Then weeffectively implement a strategy that sells high arbitrage exposure bonds and buys a portfolio of ETF5

bonds without similar exposure. To formally test the impact of delayed arbitrage, we regress the yieldspread for each month of the Taper Tantrum through December 2014 on a high arbitrage exposuredummy and in the multivariate regression, we control for observable bond characteristics. We findthat the yield spreads of the two groups are not significantly different during the Taper Tantrum.However, as the turmoil mitigates and arbitrageur reenter to restore the relative price efficiencybetween the ETF and the underlying, the yield spreads of high arbitrage exposure bonds arestatistically significantly higher for nine months. The timeline for the convergence of the two portfolioscoincides with the closing of the arbitrage opportunity. These results support the theories ofBhattacharya and O’Hara (2016) and Malamud (2016) that predict that ETF arbitrage can serve as ashock propagation channel from the liquid ETF to prices of the illiquid underlying.Our main sample includes all open‐end mutual funds and ETFs with an average allocation tocorporate bonds greater than 20%. We use this threshold because most corporate bond funds,particularly index mutual funds, are benchmarked to aggregate bond indices that have sizeablegovernment and securitized investments.6 In contrast, the majority of ETFs follow corporate bonddedicated indices with the median ETF holding 93% of their assets in corporate bonds. To addresscomparability concerns as robustness tests we execute our main tests for active mutual funds with acorporate bond allocation greater than 80%. An emerging literature focuses on the importance ofcorporate bond fund cash buffers with Jiang, Li, and Wang (2016) finding in times of volatility mutualfunds sell their holdings proportionally rather than relying on the liquidity buffer and Morris, Shim,and Shin (2017) showing in a global setting that cash hoarding is the norm. Therefore, we also consideractive mutual funds in the lowest quartile of combined liquid investments and the highest quartile offlows volatility. The only evidence of flow‐induced yield pressure is in active mutual funds in thelowest quartile of liquid assets lasting just one month. Given these findings, we cannot rule out mutualfund outflows as a possible source of fragility in a prolonged market shock. Rather than lessen fearsof strategic complementarities in mutual funds (Goldstein, Jiang, and Ng, 2017), the findings of thispaper may exacerbate them as we highlight that short‐horizon positive feedback ETFs investors mayhave the true first‐mover advantage through intraday trading.6 In 2013 Bloomberg Barclays US Aggregate Bond that had a 22.3% corporate bond allocation 017‐02‐08‐Factsheet‐US‐Aggregate.pdf6

This paper adds to a broader literature that studies asset price movements induced byfinancial institutions and arbitrageurs, by cleanly identifying the short‐horizon investors andimperfect arbitrage of ETFs as a new source of price pressure in corporate bonds. In the stock market,equity funds are shown to move underlying stock prices in a variety of settings (Ben‐Rephael, Kandel,and Wohl, 2011; Coval and Stafford, 2007; Greenwood and Thesmar, 2011; Jotikasthira, Lundblad, andRamadorai, 2012; Lou, 2012). For instance, studies by Brunnermeier and Nagel (2004) and Griffin,Harris, Shu, and Topaloglu (2011) of the technology bubble document that traditional arbitrageurs,hedge funds, amplified rather than stabilized the market. While, Cella, Ellul, and Giannetti (2013)show that stocks held by short‐horizon investors experience greater price pressure during the Lehmanbankruptcy. In fixed income markets, Feroli, Kashyap, Schoenholtz, and Shin (2014) motivated by theTaper Tantrum use nineteen years of data to show potentially destabilizing feedback from fund flowsto some market returns. Specifically focused on corporate bonds, broad studies of insurancecompanies by Ambrose, Cai, and Helwege (2012) and of mutual funds by Hoseinzade (2015) find noevidence of yield pressure. In contrast, Ellul, Jotikasthira, and Lundblad (2011) and Manconi, Massa,and Yasuda (2012) find that constrained insurance companies and investors holding securitized bondsin the crisis, respectively, engage in corporate bond fire sales. Finally using the measure of Coval andStafford (2007), Jiang, Li, and Wang (2016) show that bonds subjected to trading by extreme flowfunds, have abnormal returns in the next two quarters and in a fund family network setting Falato,Hortacsu, Li, and Shin (2016) find price pressure in the quarter of peer‐induced sales.The results of this paper also contribute to the growing research on ETFs, by identifyinganother possible unintended risk. The arbitrage response to noise traders is shown by Ben‐David,Franzoni, and Moussawi (2014) to increase stock volatility and by Brown, Davies, and Ringgenberg(2016)to lead to predictable returns. Additional studies of equity ETFs find that they increase co‐movement (Da and Shive, 2013) and lower information acquisition benefits and liquidity (Israeli, Lee,and Sridharan, 2017). In corporate bond ETFs, Dannhauser (2017) documents that ETF constituencylowers bond yields due to the migration of liquidity traders from the underlying market to ETFs.2. BackgroundThis section provides a detailed discussion of the corporate bond market and its participants.In particular, we first focus on the evolution of the market and the emergence of ETF and mutual fund7

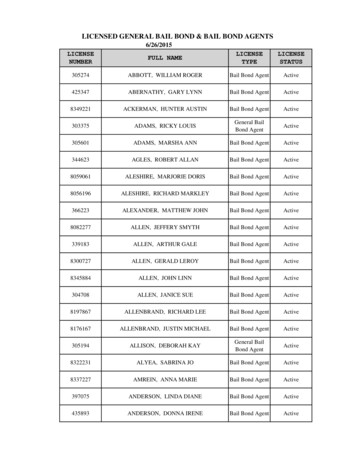

investors. Then we detail the Taper Tantrum of the summer of 2013, which we use as a plausiblyexogenous shock to fund flows.2.1. The transformation of the corporate bond marketSince the financial crisis, the corporate bond market has undergone a radical change. First,incentivized by unprecedentedly low interest rates corporations have increased their debt issuanceleading to a 56% increase in corporate debt outstanding between 2008 and 2016. Panel A of Figure 1presents the growth in corporate bond assets outstanding and the annual issuance.[Insert Figure 1]Second, regulatory pressure has altered the dynamics of the historically opaque market(Bessembinder, Jacobsen, Maxwell, and Venkataraman, 2016), in which broker‐dealers held largeinventories to facilitate trades with institutional investors. Traditionally, the majority of investors wereinsurance companies and pension funds who are broadly characterized by Bessembinder, Maxwell,and Venkataraman (2006) as long‐horizon investors. Despite the July 2002 introduction of delayedtrade reporting through the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE), Bessembinder,Maxwell, and Venkataraman (2006), Edwards, Harris, and Piwowar (2007) and Goldstein, Jiang, andNg (2017) all document that corporate bonds trade infrequently, particularly relative to other assetclasses. Pressured by increased capital requirements broker‐dealer inventory of corporate and foreignbonds has decreased 35% according to Federal Reserve Board data as plotted on the right axis of PanelB of Figure 1. The impact of their retreat on liquidity is uncertain with Anderson and Stulz (2017) andBao, O’Hara, and Zhou (2016) finding evidence of greater illiquidity in periods of stress. Conversely,Bessembinder, Jacobsen, Maxwell, and Venkataraman (2016) find that average transaction costs arenot significantly higher since the crisis, but that the traditional commitment structure is changing.Third, as the corporate bond market structure has evolved, nontraditional investors: mutualfunds and ETFs; have emerged as increasingly important investors. The accumulation of assets bythese funds, whose investment strategy and investor base is significantly different than traditionalinvestors has implications for the underlying market because of the liquidity they provide theirinvestors and thus the liquidity they may demand. The left axis of Panel B of Figure 1 shows that thecombined holdings of the nontraditional investors are nearly equal to those of insurance companies.Figure 1 also present details on the growth of ETFs in Panel C and mutual funds in Panel D, including8

the number of funds and assets under management of all long‐term taxable bond funds from ICIFactBook, as well as, corporate bond specific assets from the Federal Reserve Board. From these figuresit is evident that a large portion of growth in these vehicles has occurred since 2008 with the corporatebond assets of mutual funds tripling and ETF corporate bond assets growing by eleven times.Given the focus of this paper on ETFs and mutual funds, an extended discussion of theirstructures is needed. At the most basic level, mutual funds and ETFs are investment vehicles backedby a basket of corporate bonds. Mutual funds are distinguished by their investment mandate as eitheractive mutual funds, who attempt to outperform their benchmark, or passive mutual fund, whoattempt to replicate their benchmark. Regardless of the type of mutual fund, investors are providedwith daily liquidity. That is an investor can submit a buy or sell order for the mutual fund shares atany point throughout the day with all transactions occurring at the closing NAV.Corporate bond ETFs, the first of which was introduced in June 2002, are a hybrid betweentraditional open‐end mutual funds and closed end funds (CEFs). The unique features of ETFs allowsthem to offer lower management fees, greater transparency, and tax efficiencies (Poterba and Shoven,2002). ETFs provide liquidity to investors in two venues, the primary and secondary markets. Theprimary market, which is the direct channel linking ETFs to the underlying, is used by ETFs to handleliquidity shocks in the secondary market, to ensure that orders are filled, and to arbitrage excessivemarket price deviations from NAV. This market involves transactions between APs and the fundsponsor that exchange ETF units for a basket of the underlying securities through the in‐kind creationand redemption process. In contrast, the creation and redemption process of mutual funds occursbetween the fund and individual investors as an exchange of cash for fund shares. The secondarymarket of ETFs, is where most buyers and sellers of the ETF transact directly on the equity exchangewithout sponsor involvement.In Table 1 we present summary statistics for ETFs in Panel A, active mutual funds in Panel Band index mutual funds in Panel C. While the holdings of active mutual funds and ETFs have similarcredit quality and maturity, the holdings of index mutual funds have lower average ratings andlonger‐term to maturity. Further, the distribution of fund characteristics validates the common refrainsurrounding ETFs relative to mutual funds. For instance, ETFs have expense ratios and turnover thatare more than half of the mean level of active mutual funds reflecting the relative simplicity of ETF9

management. The average index fund expense ratio is slightly higher than the average index mutualfund, but the variation is greater for index mutual funds.[Insert Table 1]2.2. The Taper Tantrum as an exogenous shock to fund flowsAn empirical challenge of identifying potential vulnerabilities created by this new corporatebond market regimen is the absence of market shocks and resultant fund flows during the post crisisbond bull market. The exception is the Taper Tantrum of the summer of 2013 which serves as ourplausibly exogenous market‐wide shock. Prior to this event, corporate bond funds sawdisproportionate inflows relative to other asset classes (DiMaggio and Kacperczyk, 2017) as theFederal Reserve employed unprecedented policy initiatives, including open market purchases ofgovernment bonds and mortgage‐backed securities through its QE program. Initiated in Novemberof 2008, QE was intended to lower long‐term interest rates in an effort to bolster the economy.Following positive economic developments, Chairman Ben Bernanke testified on May 22, 2013 thatthe Federal Reserve would likely begin slowing or tapering the pace of its bond purchases conditionalon continued economic stability. On June 19, 2013 the Chairman held a news conference to documentthe economic justification for the purchase slowdown. Convinced that the end of QE was near, themarket responded by selling assets, in an episode commonly compared to a tantrum. Between May21, 2013 and the beginning of September both the five‐ and ten‐year Treasuries increased over 100basis points as depicted in Figure 2. The sharp reevaluation of risk lead investors to utilize the liquidityprovisions of ETFs and mutual funds by swiftly withdrawing assets. According to Trim TabsInvestment Research, a record 69 billion was withdrawn from bond ETFs and mutual fund in June2013 alone, with outflows continuing throughout July and August. The period of uncertainty wasresolved on September 18, 2013 when the Fed officially announced it would wait to begin scaling backthe QE program.[Insert Figure 2]3. DataOur corporate bond fund data begins in January 2010, in order to study a period in which theassets managed by these two investment vehicles is no longer negligible, and ends in March 2015. We10

begin by identifying corporate bond funds using the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP)Survivor‐Bias‐Free US Mutual Fund Database. In particular, we denote any mutual fund or ETF thatas an average corporate bond weighting of twenty percent or greater as a corporate bond fund. Thislow threshold is used to ensure that we have a sufficien

The liquidity transformation of mutual funds and exchange‐traded funds (ETFs) is examined as . 5 Bill McNabb, CEO of Vanguard, states "This discovery that most ETF share trading does not lead to any activity in the ETF portfolio means the impact of ETFs — and the possibility of disruption or volatility — on the primary market is .